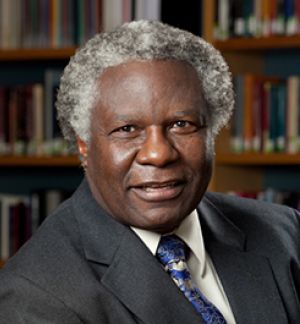

A world environment body would create unnecessary bureaucracy and divert attention from existing goals, says Calestous Juma

At a recent meeting of the World Bank in Paris, Lionel Jospin, the French prime minister, called on the United Nations to establish a world environment organisation to create and enforce environmental regulations. The call reflected the sense of urgency in addressing global environmental problems. But such a proposal might delay, rather than hasten, action.

Advocates support the establishment of an agency for a number of reasons.

First, they attribute the UN's lagging environmental efforts to the fact that environmental tasks are fragmented and performed by too many unco-ordinated agencies and treaties. Second, they decry the lack of enforcement mechanisms in most existing treaties - they claim that a new agency would have more authority and would do a better job. Third they say the agency would help transfer environmental technologies and finances to developing nations. And finally, they appeal to the need for a counterweight to the World Trade Organisation, which they consider inimical to environmental goals.

None of these reasons has a sound basis. The claim that consolidating existing international organisations will result in a stronger and more effective organisation, runs counter to the experiences of modern institutions, which are decentralising their operations. Many UN agencies are seeking to work through networks and a variety of institutional alliances focusing on specific problems. Environmental problems are diverse in character and require more specialised institutional responses.

Methods for combating global warming, for example, cannot be easily applied to conservation of endangered species.

Environmental problems also cut across different sectors, and a world environmental agency would need to cover every conceivable human activity. It would be too cumbersome to work.

There is an urgent need to share experiences and lessons, codify principles, promote guidelines and set new standards. But this is just what global treaties on climate change, biological diversity, endangered species and control of desert growth were created to do. The strength of the treaties lies in the fact that they give more power and authority to governments and citizens, not to centralised UN agencies.

It is true that most environmental agreements lack effective enforcement mechanisms. One of the reasons is that governments cannot agree on how they should work. Drawing on their experiences with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, many developing countries are concerned that a new environmental agency would only become another source of conditions and sanctions.

The real task is deciding how to get national governments to comply fully with environmental laws. If governments promote greater compliance with domestic environmental laws, they will find it easier to reflect this in international agreements. What is perceived as deficient global environmental regulations is really an indication of poor domestic housekeeping.

Most developing nations cannot meet their obligations under various environmental treaties. They say this is partly because the richer nations have not honoured their commitments to assist them with technology and finances. There is no guarantee that the new agency will perform better in this regard.

In addition, developing nations have consistently argued that environmental conservation should be promoted as part of their overall economic goals, as agreed at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Creating a new agency focusing on environment over development, as is proposed, would amount to reneging on this historic agreement.

The claim that a new agency would serve as a counterweight to the WTO is equally flawed. The WTO undoubtedly needs to take environmental issues seriously. But this would be more effectively done by integrating environment into trade activities, not simply by creating a new agency.

Unfortunately, the debate on creating a new agency diverts attention from more urgent tasks. All nations need to do more to meet their obligations under international treaties. Much of this involves domestic efforts to cut pollution, protect wildlife, and conserve soils and

freshwater. Industrialised nations should also meet their international commitments by sharing experiences and forging technology partnerships with developing nations.

Tackling the world's environmental problems calls for urgent action. There is no time to waste on launching a costly, politically divisive and bureaucratic structure with no clear organising principle.

Mr Jospin's call is tantamount to saying a bigger Titanic will guarantee the safe crossing of the Atlantic. It will not.

The full text of this article is available via http://www.financialtimes.com/.

Juma, Calestous. “Stunting Green Progress.” Financial Times, July 5, 2000