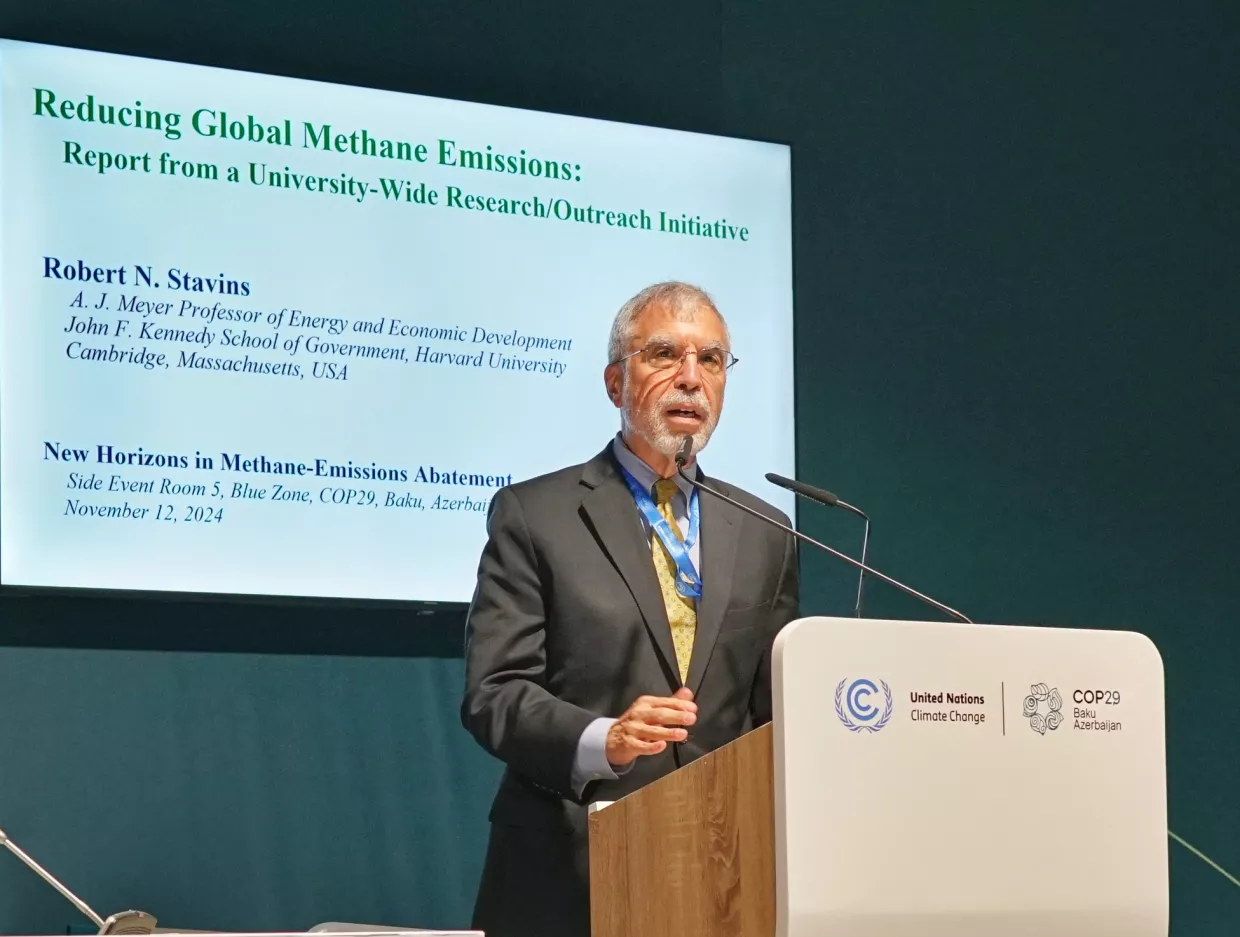

In a presentation that described some of the highlights of the first two years of the Harvard Methane Initiative, Stavins framed the subsequent discussion by reminding attendees that while methane has received considerably less attention from governments, NGOs, academia, and the news media than carbon dioxide (CO2) as a driver of climate change, methane emissions abatement efforts can be very powerful.

“The absolute quantities of methane are much less than the absolute quantities of CO2 that go into the atmosphere, and whereas the half-life of CO2 exceeds 100 years, most of the methane is out of the atmosphere after only a decade or so,” he said. “On the other hand, methane has very high global warming potential per unit compared with CO2. The traditional CO2 equivalents measure has always been 100 years, in which case each unit of methane is 28 times more important than each unit of CO2, but if we look over a 20-year horizon, then it is 84 times as effective in terms of global warming.

Stavins lauded the Harvard Initiative, launched in 2023, for its ambitious research agenda and effective engagement with key stakeholders designed to achieve meaningful and sustained progress in reducing CO2 emissions. The Initiative and its research teams were involved in seven distinct research/outreach projects during year one, he said, and have launched 14 additional projects in year two, including those focusing on methane mitigation in agriculture, waste/landfills, and the oil and gas sector.

Osho, who leads the development and implementation of IGSD’s subnational work on mitigation of short-lived climate pollutants, shared her thoughts from the perspective of the global south. India, she said, is one of the three largest emitters of methane globally with most coming from waste and agriculture.

“Unlike steel, where we have technological challenges, our problems arise from the fact that scaling solutions in these sectors is much harder, surely because of the fact that we are a country of 1.5 billion people,” she said. “Seventy percent of India’s population is either directly or indirectly dependent on agricultural livelihoods and incomes, so moving people away from traditional practices that have been in practice for several generations is harder to begin with.”

Osho said efforts are now being focused on developing financial incentives to help reduce methane emissions in India’s agricultural economies in line with the Global Methane Pledge. She explained that her organization and others are working with sub-national governments to gather helpful data and simple supply chain methodologies that will reduce emissions in waste and from cattle.

Smith spoke of the important work being done at the Global Methane Hub to support efforts across multiple sectors to help “pull the emergency brake on methane” in the energy, agriculture, and waste sectors.

“Reducing [methane emissions] is really the only way we know of to substantially cut warming over the next several decades, which is the critical time horizon… to stave off catastrophic changes to our climate, irreversible tipping points that we know are coming,” she argued.

Smith said that the E.U. has made progress by adopting import standards for natural gas, and stakeholders throughout the world are gaining access to improved methane emissions accountability measures.

“We are entering a whole new era [of accountability] with satellite data,” she said. “This will be publicly available information, and we have seen that this information can drive action in places like Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, where leaks have been addressed as a result of seeing the invisible plumes.”

Sander, who is IRRI’s Senior Scientist for Climate Change and leads IRRI’s country office in Thailand, focused his remarks on new approaches to mitigate methane emissions from rice production. Only a small percentage of funding is currently earmarked for research on methane abatement in rice, he said, at a time when the relative mitigation potential for rice is much greater than that of livestock and croplands.

“There are plenty of mitigation options in rice production across the entire rice cultivation cycle, starting with preparation, [and] proper leveling of the fields, which can help manage the water and reduce fertilizer and seed use,” he remarked. “Direct seeding of rice can reduce emissions. Choosing the right variety. Shorter duration varieties, obviously, have lower emissions. Deep placement of fertilizer can reduce nitrox oxide emissions. Also…switching from flooded fields to dry fields has a very high mitigation potential. The other big factor is rice residues. The more straw, the more organic amendments are being put into the rice fields, the higher the methane emissions.”

Methane abatement efforts in rice production can be taken both through bottom-up and top-down strategies, Sander stated, including digitized rice production monitoring and satellite tools to monitor water management.

The panelists also responded to questions from members of the audience, including ones about how to engage small-scale farmers in mitigation efforts, the possibility of eliminating incineration in waste management, and on the most effective long-term solutions for reducing methane emissions.

Stavins closed the discussion by referencing the potential of science and research for advancing policy solutions to environmental problems like methane emissions.

“As an economist, I will note that it is important to bring down the net costs of reducing methane emissions. I say ‘net costs’ because abatement may be costly, but, for example, in some cases yields can be increased at the same time. That phenomenon — in the form of keeping more of a merchantable product (natural gas) in the pipeline — is making a difference in the oil and gas sector. Ultimately, this means greater adoption and diffusion of abatement technologies, whether induced by public policies or through independent market forces.”

Follow the Harvard Project at COP-29 on Tumblr