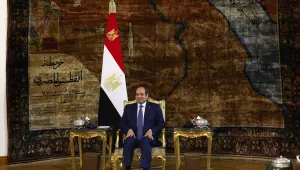

CAIRO—In the past three years since the overthrow of the Hosni Mubarak government, on my regular visits to Cairo I have watched with fascination, pride and hope the birth of Arab citizens and the sudden emergence of a public political sphere—an open, pluralistic space where people from different ideological and cultural perspectives could freely compete for political power and legitimate, democratic control of the government. I have witnessed very different things in Cairo this week, during and after the referendum on the new Egyptian constitution that was drawn up in recent months by the interim government that was installed by armed forces commander General Abdul Fattah Sisi, and that also has led a tough campaign to outlaw the Muslim Brotherhood.

The constitution was approved by an astounding, and totally expected, 98 percent of voters, for most of those who opposed it boycotted the process altogether, either from conviction or intimidation. The vast majority of international and local observers found almost nothing seriously wrong with the mechanics of the voting, so the 98 percent approval accurately reflects the sentiments of those who voted. Yet many observers criticized the wider political environment that did not permit a serious debate about the merits or the constitution or the unilateral political process that created it.

The frenzied mass support for Gen. Sisi and against the Muslim Brotherhood is genuine, and reflects a peculiar combination of Arab events and sentiments that are only found today in Egypt. This is why I suspect that what we witness these days in Egypt cannot be analyzed by using political criteria, but rather requires the tools of the anthropologist. There is no real political or ideology involved here. There is mainly biology driving events these days, primarily the anthropological need of tens of millions of Egyptians to get on with their lives and—as they see it—prevent the collapse of this society that has functioned without interruption for over 5000 years. The citizen and public political sphere that were being born in the past three years have momentarily receded from modern history, for they have been overshadowed by the herd and its need for self-preservation, the biological cell’s need for water and protein, and Egyptian society’s need for order.

Uniquely Egyptian conditions of demography, authority, economy and democratic transformations may help us understand what is going on in this country. Babies are a good starting point for such clarity. Every six months, over one million Egyptians are born. In 2011, according to government figures, 2.4 million Egyptians were born. This was even higher than the figure for 2010. Tens of millions of Egyptians before 2011 were already straining to make ends meet and give their children a decent future. Their conditions and prospects have worsened since then due to the economic slowdown in the country.

A small majority of voters from among the population of 85 million Egyptians elected Mohammad Mursi as president in 2012 alongside a Muslim Brotherhood-dominated parliament. By mid-2013, a likely strong majority of those 85 million Egyptians were frightened by the combination of incompetence and autocracy that the Muslim Brotherhood practiced during its year in office, and chaos in the streets at times. Popular demonstrations in June 2013 opened the way for the Sisi-led armed forces to remove the Mursi government, and to follow up with a severe crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood party.

The 98 percent approval for the new constitution represents a mass craving for some normalcy and order. The interim government represents a deep and persistent power structure in Egypt that has dominated society for over half a century. It includes the armed forces and its many appendages, the massive state bureaucracy and its associated middle class citizenry, the remnants of the National Democratic Party and its supporters and beneficiaries, and the capitalist private sector barons who grew rapidly since the Anwar Sadat years of the 1970s.

Whether Gen. Sisi runs for president or not seems to me not the main issue; more significant is whether the existing interim government and this power structure that it mirrors has the capacity to meet the needs of the 85 million Egyptians and the 2.4 million being born every year. Nearly seven million new Egyptians have been born during the last three years of transformation and turbulence.

In the past three years, Egypt has been ruled by four different types of leaderships that have all faced the same challenges to improve the day-to-day lives of the Egyptian population in terms of jobs, income, services, opportunity and hope. The four—Husni Mubarak and the National Democratic Party, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the Muslim Brotherhood, and now the current transitional government installed by the armed forces again—offer very different worldviews and operating systems. Yet, those 85 million citizens get up every morning and get on with their lives without seeing any massive changes in how their society is ordered or their own material condition.

When they become scared, they stop acting like individuals, and they move as a herd that instinctively seeks the closest water hole and food source. Thriving can wait. Survival is the imperative today, and order is its handmaiden.

Rami G. Khouri is Editor-at-large of The Daily Star, and Director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut, in Beirut, Lebanon. You can follow him @ramikhouri.

Khouri, Rami. “Anthropology, Not Politics, Rules in Egypt.” Agence Global, January 20, 2014