Perhaps it is because Egypt has always been the cinema capital of the Arab world, and everything and everyone in Egypt is on a public stage watched by people across the entire region. Perhaps it is because from 1952 they suffered the devastating humiliation of seeing their country plummet from the pinnacle of Arab achievement and respect to the gutter of mediocrity and marginalization. Or perhaps it is because they experience in their bones what it means to be a genuine country with strong institutions, like the armed forces, the judiciary, the presidency, universities, and many other civil society organizations.

Perhaps it is because of all this and much more that these Egyptians will not easily give up, will not roll over and abandon their quest for a new and productive political order to either the thugs of the military or the thugs of the Muslim Brotherhood, or to debilitating weariness and despair. For two and a half years now, Egyptians have pushed ahead to reconfigure and re-legitimize their state in the face of immense obstacles, hardships, political tensions and death, unwilling to give up. All along, they have had three main goals, which still seem to drive conflicting passions during this stage, when the interim president, the armed forces and an array of political groups issued the declaration late Monday night that charts the way forward to a new political order in the country.

Those three goals seem to me to be: a) a credible constitution that has widespread support among, and reflects the values and rights of, an overwhelming majority of Egyptians, including Islamists, secularists and everyone else in between; b) a political order shaped by the rule of law and democratic pluralism, anchored in civilian authority, but with the armed forces in the background preserving the integrity of the state; and, c) a national socio-economic and governance system that respects the basic dictates of social justice, so that tens of millions of hard-working and decent Egyptians are not marginalized at conception and pre-ordained from birth into a life of poverty, vulnerability and powerlessness.

I chuckle every time I read a text from the United States advising Egyptians on how to become democratic, given the strange shape of American democracy today when the Congress cannot seem to agree on anything, and every issue is transformed into an existential ideological battle. It is also hard to take seriously democratic advisories from an American system whose foreign policy remains a leading global purveyor of criminality, death, occupation, colonization, exploitation and mass human suffering. I have great respect and affection for many things in the United States, but offering advice to Egyptians or other Arabs on how to become democratic is not one of them. No wonder even American journalists, some of whom do outstanding work, are finding it difficult to work in Egypt today, because of the resentments against their country and its policies by both major sides in Egypt.

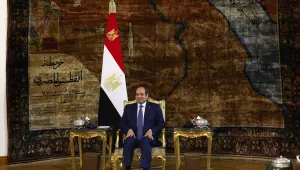

Instead, I suggest, we would serve Egypt and its people much better by simply stepping back from intervening in their lives and minds and simply acknowledging, understanding and admiring their indomitable determination to get through this constitutional transformation with a new political order that is both legitimate in respecting people’s rights and effective in meeting people’s basic needs. In Egypt’s transition since January 2011, new constellations of actors routinely take center stage. Now it is the interim presidency of Adli Mansour and his imminent new cabinet, the armed forces who named him, the Tamarrod campaign that rallied tens of millions of citizens to challenge and then remove former President Mohammad Morsi, and the Noor Party and other Salafist Islamists who are the key players of the moment.

The old-guard Mubarak-era fulul are said to be active in this constellation, but like many other forces in Egypt today, they live in the shadows, hard to touch and to know. The Muslim Brotherhood will regroup and redefine its participation in national politics, already making its inner splits more visible in public, also perhaps retreating to more comfortable spaces in the shadows that were its home for half a century. We read much about the role, or non-role, of the American embassy in current Egyptian developments, and that, too, is in the realm of the shadows -- perhaps of the imagination.

I am awed by Egypt and the Egyptians, who persevere to perform and achieve on their great public stage that which no Arab country has ever achieved: citizens who define their state, their national values, their rights, and their governance system, in a political process of national self-determination that also will see them ultimately as sovereign. They quarrel and negotiate, bluff and boycott, dare and jab, spend hours in meetings and negotiations, and only very occasionally shoot to kill. They mostly move ahead, but sometimes sideways and backwards.

New actors regularly take the stage, and are either validated or repudiated by the only force that matters: the will of the citizenry. That will is now being negotiated and defined in multiple acts on that great Egyptian stage, in competing public squares in the street, in the media, in the constitutional revision process that will start again soon, and finally in new elections for the presidency and the parliament. They forge ahead, undeterred by their own turbulence and self-inflicted traumas, keeping their eye on the great prize of constitutionalism, citizenship and sovereignty.

I stand in awe of Egypt and the Egyptians, humbled and buoyed by their relentless quest to create the first modern Arab country that makes sense, because it is the result of the handiwork of its own citizens.

Rami G. Khouri is Editor-at-large of The Daily Star, and Director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut, in Beirut, Lebanon. You can follow him @ramikhouri.

Khouri, Rami. “In Awe of Egypt and the Egyptians.” Agence Global, July 10, 2013