Last week, a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine panel affirmed the goal of eliminating highly enriched uranium (HEU) from civilian use, while recommending step-wise conversion of high performance research reactors using weapon-grade uranium fuel and that the White House coordinate a 50-year national roadmap for neutron-based research. (Full disclosure: I sat on that committee, and oversaw the NNSA reactor conversion program from 2006-9; this post, however, represents my views, not necessarily those of the committee or NNSA.)

Research reactors contribute enormously to our knowledge, prosperity, and well-being. They train scientists and engineers, advance basic science, test and qualify power reactor fuels, test and create advanced materials, and diagnose and treat disease.

Before the dangers of proliferation and nuclear terrorism were fully and widely understood, over two hundred research reactors (including some defense-related facilities) in dozens of countries were fueled with HEU—much of it weapons grade—mostly with U.S. or Soviet assistance. Beginning in 1978, the United States reversed course, and at first in parallel with the Soviet Union (which pursued lower enrichment levels, but still above 20% U-235), and later in cooperation with Russia, began to assist countries to convert the reactors to low enriched uranium fuel (LEU) (below 20% U-235), and to repatriate the fresh and spent fuel to secure storage in the United States or Russia. These efforts proceeded with great urgency after the September 11, 2001 attacks, as the specter of nuclear terrorism suddenly loomed larger.

By 2014, 20 U.S. reactors had been converted, as well as 47 foreign reactors in 34 countries; an additional 20 HEU research reactors in 11 countries were closed. Thus, the number of HEU civilian research reactors operating or planning to operate has been reduced to 74. Recently, however, progress has slowed. Two factors, one technical and one not explain this slowdown.

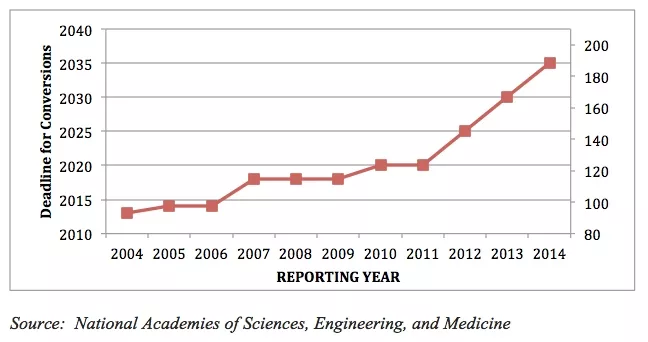

First, designing and manufacturing the high-density fuel required for conversion of high performance research reactors in the United States and Europe has proven to be far more challenging than originally estimated. As a consequence, the deadline for completing conversions has slipped from 2014 in 2004 to 2035 in 2014.

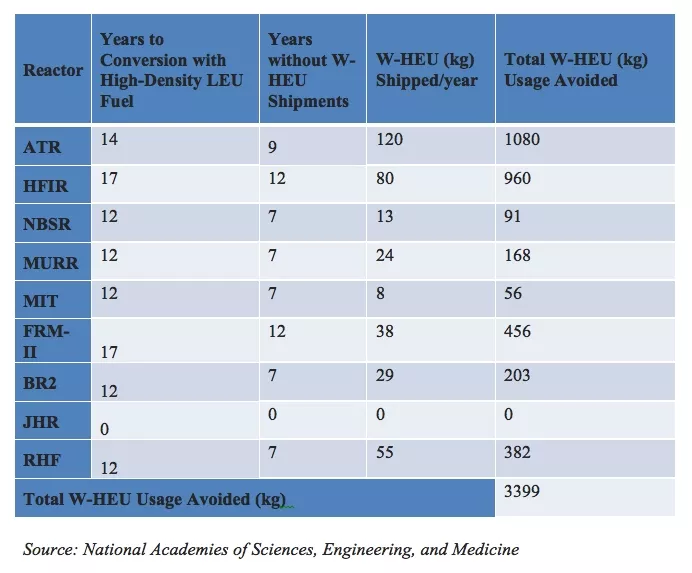

Moreover, that high-density fuel will be available to support conversions by 2035 is by no means assured. Significant technical risk inheres. Any additional design or manufacturing problems will further delay the conversions. As a consequence, the committee recommended a step-wise interim conversion to 45 percent or less U-235 fuel. Such a move would significantly reduce the use of weapons-grade HEU, and enable conversion work to continue—maintaining significant technical expertise.

This recommendation should in no way be construed as lack of support for eliminating civilian use of HEU. Rather, it is recognition of the fact that estimates of when conversion would be possible have changed, and an effort to minimize risk in light of those changes. The committee judges that such interim conversions could be accomplished with minimal delay to ultimate refueling with LEU. If that judgment proves wrong, the reduction in risk by halving the enrichment levels outweighs the additional risks incurred by pushing out final conversion to LEU.

Second, while Russia operates a plurality of research reactors fueled with HEU, about 40 percent, Moscow’s commitment to conversion of those reactors is uncertain. Russia, with U.S. assistance, has converted all Russian-supplied HEU research reactors outside the former Soviet Union. Moscow also undertook a pilot conversion study of its domestic HEU reactors in cooperation with the United States, and converted one reactor. Unfortunately, the chill in U.S.-Russian relations has effectively curtailed cooperative threat reduction efforts within Russia, although there was significant resistance to conversion even before political relations declined. The Academies committee recommended that technical and scientific interactions with Russia should continue with the goal of minimizing the use of HEU; this aims to protect, to the extent possible, the 20-year investment in time and money to develop the professional relationships that made cooperative threat reduction possible.

Through several programmatic evolutions, U.S. efforts to convert HEU research reactors and to repatriate fresh and spent fuel, have significantly advanced efforts to prevent nuclear proliferation and terrorism. Unavoidable technical and political factors have slowed this progress. To maintain the program’s momentum, fresh thinking will be necessary and deserves support from the executive and legislative branches of government.

Tobey, William. “Fresh Thinking on Highly Enriched Uranium Research Reactor Conversions .” February 3, 2016