Cracks are increasingly discernible in the famous “special relationship.” Can they be repaired? If not, could Israel’s national security survive the loss of American military aid?

Note

The following essay is a modified excerpt from Dr. Freilich's forthcoming book, Israeli National Security: A New Strategy for an Era of Change.

Israel's relationship with the United States is a fundamental pillar of its national security. Militarily, diplomatically, and economically, American support has for decades been a vital strategic enabler. For consultations on emerging events, Washington is usually Israel's first and often sole port of call, almost always the foremost one, and inevitably the primary address when planning how to respond to such events. Indeed, Israel's reliance on the United States is so great today that the country's very survival is at least partly dependent on it—with, as we shall see, a variety of consequences not all of which are salutary.

I. The Origins and Growth of a “Special Relationship”First, some historical background. Contemporary readers may be surprised to learn that, until the late 1960s, the Israel-U.S. relationship was actually quite limited and even cool. Only in the aftermath of the Six-Day War (1967) and especially the Yom Kippur War (1973) did it begin to evolve into a more classic patron-client setup, and not until the 1980s did it start to become the institutionalized and strategic “special relationship” we know today.

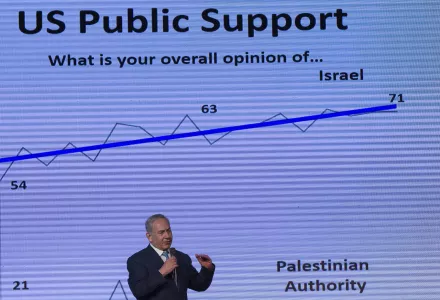

And it truly is a special relationship: a largely unprecedented arrangement for the U.S. and a critical one for Israel, encompassing ties in all spheres of national life—military, political, economic, diplomatic, and cultural. Even through episodes of government-to-government disagreement and discord, not to mention the continual criticism of various Israeli polices by American elites of one stripe or another, popular support for Israel remains high in the U.S., by some measures higher today than ever, and the security relationship itself remains not only fundamentally strong but extraordinarily close.

Let’s count the ways. Economically, the United States is Israel’s single biggest trading partner (only the EU taken as a whole is larger), with bilateral trade in 2016 running at approximately $35.5 billion. The two countries signed a free-trade agreement in 1986, the first such bilateral deal ever concluded by the U.S. Over the years Washington has, in addition, provided emergency economic assistance and loan guarantees.

Militarily, total American assistance to Israel, from 1949 to 2016, amounts to a whopping $124 billion, making Israel the largest beneficiary of American military aid in the post-World War II era. In 2007, the two countries concluded a ten-year, $30-billion package, thereby providing the IDF with the fixed financial basis it badly needed for purposes of planning its force structure; a second ten-year package, for $38 billion, was signed in 2016.

The import of this aid can be measured not just in the absolute dollar amount but in the way it is disbursed. Since 1981, all assistance to Israel has been in the form of grants, not loans, and each annual sum arrives in its entirety at the beginning of the year rather than in installments. Israel is also the only recipient that for decades was allowed to spend part of this assistance for procurement in Israel itself rather than in the United States—although that concession is now being phased out.

It is hard to imagine two countries engaged in closer or more intensive strategic consultation than Israel and the United States.

Moreover, the annual aid package, large as it is, does not include a variety of special programs like the rocket-and-missile-defense systems (Iron Dome, Arrow, and others) that have significantly added to the total level of U.S. aid. (For the record, it should be noted that, since Israel has always been required to spend the major part of the funds in the U.S., the aid functions simultaneously as a giant subsidy to American arms manufacturers—and that the U.S. military greatly benefits from letting Israel test and improve new technologies, Iron Dome being a prime example.)

Some constraints were once applied to U.S. arms sales to Israel, but these have mostly been lifted over the years, and Israel generally has access to the latest American technologies. In 2005, for example, Washington supplied Israel with “bunker-busting” bombs that had never been sold to any other country, and then accelerated the delivery of more such weapons during the 2006 Lebanon war. Israel was also the first foreign country to purchase F-35s, the most advanced American fighter. In practice, the United States is almost Israel’s sole foreign source of sophisticated weapons, some of them co-developed and co-produced in Israel.

ind the aid is a policy, a set of agreements, and a web of strategic activities. Since the 1980s, the United States has been committed to preserving an Israeli qualitative military edge (QME) over any possible combination of hostile Arab armies, an arrangement enshrined in a number of executive and congressional initiatives. When it comes to strategic consultation, it is hard to imagine two countries engaged in closer or more intensive bilateral exchange at all levels. Not only do Israeli prime ministers meet on a regular basis with the American president, senior officials, and congressional leaders, but the national-security establishments of the two countries enjoy intensive and ongoing contact, including an endless array of visiting delegations and professional teams as well as working groups that convene regularly and often.

The benefits of all of this dialogue are easily stated. Over the years, the United States has consistently demanded that Israel not “surprise” it by taking controversial measures without at least first consulting. And, with rare or partial exceptions that we’ll explore later on, Israel has faithfully done as asked.

Then there are the many examples of actual military cooperation. These include the linking of Israel to the American early-warning system that detects missile and rocket launches around the globe; joint military exercises; the pre-positioning in Israel of American weapons and munitions in order to save time in case of war, with Israel also being allowed to use some of these items (especially those with a brief shelf life) on a regular basis; mutual sharing of information and experience in the area of domestic security; and intelligence cooperation in the fields of counterterrorism, cyber security, and non-proliferation.

So deep has the strategic relationship become over the decades as to raise the possibility of an actual defense treaty between the two countries. Perhaps the closest this has come to serious consideration was under Prime Minister Ehud Barak (1999-2001), who, in seeking dramatic breakthroughs to peace, held talks with the Clinton administration on a comprehensive U.S. security guarantee that might help assuage any post-peace-deal anxieties on the part of the Israeli public. But, at the time, few on either side were eager to proceed—in effect, Israel already enjoys the benefits of such a treaty—and in any case the peace talks collapsed. In the end, both sides favored a more limited agreement.

Finally, in addition to providing Israel with the military wherewithal to ensure its security, the United States has also used its political and diplomatic leverage, in a variety of international forums, to protect Israel from an endless array of injurious resolutions concerning the peace process, various military and diplomatic initiatives, and, of particular note, Israel’s alleged nuclear capabilities. Thus, between 1954 and 2011, the United States vetoed a total of 38 one-sided or clearly anti-Israel resolutions in the UN Security Council, ten in the decade between 2001 and 2011 alone. In addition, Congress made U.S. payments to the UN contingent on acceptance of Israel in the Western and Others Group. Thanks to unequivocal American support, the 2006 war in Lebanon became the first military confrontation in the history of the Arab-Israeli conflict in which Israel did not face limits on the time it had to achieve its military objectives before the great powers would intervene to end the fighting.

Although the United States has long been committed to an Israeli withdrawal from most of the territories captured in the 1967 Six-Day War, it has historically backed Israel’s view that UN Security Council Resolution 242, the bedrock document on which all peace negotiations have rested, does not necessarily require a completewithdrawal. Instead, American leaders have variously spoken of Israel’s need for “defensible borders,” of the possibility of “minor adjustments,” of Israel incorporating the “settlement blocs,” and other such formulations. Washington also shares the view that a final agreement must address Israel’s security concerns, and backs Israel’s opposition to a large-scale return of Palestinian refugees and its demand that Palestinians recognize Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people.

II. Is the Tail Wagging the Dog?

Despite the strength of the strategic relationship between Israel and the United States, and the robust support it enjoys from the American people, the arrangement is hardly without influential critics; nor is it immune to cultural and demographic realities potentially injurious to its stability and longevity. To these we can now turn.

Criticism of the strategic relationship comes in several guises. But the basic charge is this: instead of aligning itself with the priorities of its American benefactor, Israel has repeatedly and hot-headedly gone its own way, flagrantly disregarding American national interests and thereby damaging U.S. relations with other powers and hobbling Washington’s freedom of maneuver. In short, Israel, the tail, has been defiantly wagging the dog of American foreign policy.

Is there any truth to this charge? Israel does act independently at times, and possibly more often than one might expect in a totally asymmetrical relationship of this sort. In fact, however, with the exception of a few cases that I’ll get to shortly, considerations of U.S. policy and national interest have been the primary determining factor in virtually all major national-security decisions made by Israel ever since the “special relationship” evolved in the 1970s and 80s and in many instances long before then. Unless one expects nearly complete pliability and subservience, Israel’s acts of independence or “defiance” have been very few.

The truth, indeed, is nearly the opposite of what the critics contend: by now, I would argue, Israel has lost much of its own independence to the United States. Since this statement would no doubt be contested strongly by many in both Israel and the U.S., let me substantiate it with a brief return to history.

Far from acting in willful disregard of American national interests, Israel by now has arguably lost much of its own independence to the United States.

In the run-up to the Six-Day War of June 1967, at a time when U.S.-Israel relations were still quite limited, Israel took preemptive action against the Arab powers vowing its extinction. It did so, however, only after a protracted waiting period and not until President Lyndon Johnson informed it that he would not be able to honor an earlier U.S. commitment to keep open the Straits of Tiran, which Egypt had closed to Israeli shipping. Six years later, in October 1973, the primary reason Israel refrained from launching a preemptive strike, even once the imminence of an Egyptian and Syrian attack had become undeniable, was fear of adverse American reaction—a hesitation that cost it dearly on the battlefield. Both of these cases of circumspect Israeli behavior preceded the emergence of the “special relationship.”

In 1982, Israel launched the first Lebanon war only after at least partially convincing Washington of the need for a large-scale military operation, a diplomatic process that took the better part of a year. In 1991, it refrained from responding to direct Iraqi missile attacks on its population out of deference to American pressure. During the second Lebanon war in 2006, compliance with the American demand that it refrain from attacking Lebanon’s civil infrastructure left the IDF without a viable military strategy and was one of the main causes of the severe difficulties Israel encountered in that conflict. Two years later, concern over a potential lack of support by the incoming Obama administration led Israel to terminate a counterterrorist operation in Gaza earlier than intended.

Then there was Israel’s decision in the mid-to-late 2000s not to strike the Iranian nuclear program, which it most definitely regarded as an existential threat. This was a particularly vivid example of the importance Israel attaches to the U.S. position, and especially to the need for American support for military action. True, American opposition was not the only consideration—some in Israel doubted the efficacy or even the feasibility of a strike on Iranian facilities—but it was certainly a main and quite possibly the decisive one. Conversely, Israel’s reported strike against a Syrian reactor in 2007 was conducted with American understanding, if not outright support, but only after intensive consultation and after Washington made it clear it would not attack on its own.

The American position has also had an enormous impact on the “peace process” with the Arabs. Although, when it came to seeking peace with Egypt, Israel had a strong incentive of its own to proceed, some of the concessions it made, especially at the Camp David summit in 1978, were largely owing to American pressure. Indeed, President Jimmy Carter reportedly threatened Prime Minister Menachem Begin that any hesitation on his part to sign the proposed agreement might cost Israel its nuclear capabilities: “Don’t rely on Dimona [where Israel’s nuclear reactor is located]. I will see to it that you don’t have Dimona, either.”

In the early 1990s, after seizing the initiative that would result in the Oslo agreement, Prime Minister Yitzḥak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres closely coordinated Israel’s negotiating positions with the Clinton White House, which in 1993 succeeded the significantly frostier administration of George H.W. Bush. Later in that same decade, Prime Minister Ehud Barak met with President Bill Clinton to gain American support for his highly ambitious plan (mentioned above) to achieve peace with both the Palestinians and the Syrians, and then spent the following year in extraordinarily close contact with Clinton and other top American officials. At the Camp David summit in 2000, and again prior to accepting the “Clinton Parameters” later that year, Barak deliberately aligned his strategy and bargaining posture with Washington.

Barak’s successor Ariel Sharon, although initially dismayed by the second Bush administration’s “Roadmap for Peace,” rapidly adopted it and closely coordinated with Washington the 2005 unilateral withdrawal from Gaza. In fact, it was the American position that led to Sharon’s decision to withdraw from Gaza in its entirety, to dismantle all of the Israeli settlements there, and to remove four settlements in the West Bank as well. The White House knew the details of the disengagement plan long before it was divulged to senior Israeli officials—including the defense minister. Later, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert similarly sought coordination with the United States at the 2007 Annapolis conference and with regard to his own far-reaching peace proposal to Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas in 2008.

Freilich, Charles D. "Has Israel Grown Too Dependent on the United States?" Mosaic, February 5, 2018.