25 Years of Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Threats

1. Introduction

When the Republic of Kazakhstan declared independence from the Soviet Union on December 16, 1991, its leaders found themselves in possession of 1,040 nuclear warheads, seven heavy bombers, and hundreds of intercontinental ballistic missiles and other nuclear weapons-related equipment. These weapons and delivery systems were only one part of the new country’s inheritance. Kazakhstan now held one of the largest and most diverse systems for producing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in history.

Nuclear materials and sensitive equipment remained strewn across the massive Semipalatinsk nuclear weapons test site, where the Soviet Union conducted its first nuclear weapons test and followed with 455 more. Just to the east, a metallurgy facility in the town of Ust-Kamenogorsk held enough highly enriched uranium to make about 24 nuclear weapons. Further west, the city of Stepnogorsk housed an industrial-scale facility ready to produce and weaponize several hundred metric tons of tons of anthrax and other biological agents if war broke out between the Soviet Union and the United States. At a nuclear reactor along the Caspian Sea, Kazakhstan now possessed one of the largest stocks of weapons-usable plutonium and highly enriched uranium in the world—enough to produce around 775 nuclear weapons. Still other sites held capabilities needed for developing nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. Skilled scientists and experts with experience relevant to running WMD programs went unpaid or under-employed. Many left the country altogether.

The work of reducing WMD threats remains as critical today as it was in December 1991. Though these threats have changed in time, the world still faces WMD challenges as daunting and diverse as those Kazakhstan inherited.

August 29, 2016, marked the 25th anniversary of President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s decree closing the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site. During these two and a half decades, Kazakhstan has remained committed to countering the incredible range of WMD risks in its own territory. As WMD threats in Central Asia and globally have evolved, its leaders have responded by broadening their domestic activities and promoting nonproliferation heavily with the international community.

Given the breadth of legacy WMD systems Kazakhstan housed upon independence, it offers a unique set of cases within a single country in terms of both the scale of its WMD threat reduction needs and in the various ways and means it employed in meeting these needs. The Kazakhstanis took several approaches to nuclear security efforts that its Soviet-era legacy required. Kazakhstan has conducted multiple types of biological security work as well. In the 1990s, it dismantled a large-scale biological weapons program. Today, it is participating in comprehensive efforts to bolster security of biological materials, gainfully employ those with dual-use knowledge in the biological sciences, and expand public health capacities. Finally, Kazakhstan now takes deliberate steps to leverage its WMD experiences to promote nonproliferation and arms control among the international community. These lines of effort create a rich historical tapestry from which to derive lessons for the future of countering WMD threats.

A number of scholars, reporters, and practitioners have conducted detailed examinations of Kazakhstan’s WMD-related actions since independence. This includes the leadership and staff of the National Security Archive at George Washington University, who have focused extraordinary efforts on understanding the history of the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program that facilitated many of the successful efforts conducted in Kazakhstan.[1] This paper will build on this previous work by reexamining it through the lens of themes and insights we have gained from personal experience.

Building on our past work and previous written analysis, we will focus on key events and decisions that may most directly inform future decisions regarding missions to reduce WMD threats. The international community regularly wrestles with decisions of how to conduct countering-WMD work. The 2013-14 Syria chemical weapons case included decisions to remove most materials for destruction abroad, but to allow international inspectors to oversee destruction of most equipment within Syria despite incredible security risks. Likewise, various decisions between 2011 and 2016 led Libya to secure and destroy most of its remaining chemical weapons in country, but to later remove the final stocks of precursor chemicals rapidly due to the encroachment of Islamic State forces.[2] We know from our own experiences with these deliberations how complicated they can be, at times to the point of delaying or deferring much-needed action. We believe examining these types of decisions by Kazakhstan should help the international community to game out possibilities for future WMD elimination work that may be required in various contingencies, for example regarding North Korea or terrorist organizations that have pursued WMD capabilities.

This report will begin with a brief overview of the current global WMD threat landscape in order to identify the types of challenges to which we have tailored our review of Kazakhstan’s work. It then provides a review of key elements of Kazakhstan’s efforts to counter WMD threats since the country’s independence. We then offer several specific lessons and recommendations. Our hope is that this report will offer unique insights relevant to the challenges on our doorstep today and likely to come in the future in countering nuclear, biological, and chemical threats.

[1] Materials from the National Security Archive’s Nunn-Lugar Revisited project and other collections can be accessed at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/

[2] Christine Parthemore, “Technology in context: lessons from the elimination of weapons of mass destruction,” The Nonproliferation Review, 23:1-2, (2016), page 84, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10736700.2016.1177263?needAccess=true; Missy Ryan and Greg Jaffe, “As ISIS closed in, a race to remove chemical-weapon precursors in Libya,” The Washington Post, September 13, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/as-isis-closed-in-a-race-to-remove-chemical-weapon-precursors-in-libya/2016/09/13/85094326-78f7-11e6-beac-57a4a412e93a_story.html

2. WMD Threats Today

As of this writing, news of WMD threats is dominated by terrorism, continued use of common chemicals in weapons deployed in Syria, and one of the few remaining states likely to have extensive nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons programs: North Korea.

Beyond the headlines, many experts are now focused on specific ways in which WMD threats have evolved in terms of the actors of greatest concern and their intentions. The rise of WMD terrorism is perhaps the most decisive trend since the end of the Cold War. This is particularly true for biological threats. Large-scale state-based bioweapons programs such as that of the former Soviet Union have mostly been dissolved, and most countries have pledged not to produce them. Coinciding with this progress, individuals, cults, and terrorist organizations have attempted to employ biological weapons, thankfully with only mixed success to date.

Developments in the field of biotechnology and the now-regular need to combat naturally occurring infectious diseases are reshaping the WMD threat landscape and the contours of biological threat reduction work. Synthetic biology and other advances in biotechnology are driving new concerns that biological weapons could become customized for specific individuals or populations, more resistant to countermeasures, and more accessible to those with less tacit knowledge and expertise. The risks of terrorists and lone actors interested in bioweapons, coupled with the need for countries around the world to improve their general abilities to counter infectious diseases, are driving work to counter biological threats toward comprehensive approaches that consolidate and secure dangerous materials, train workers, detect and track outbreaks, and develop other capacities that combine to address both defensive and civilian needs.

The world is undergoing progress and setbacks regarding chemical weapons. On one hand, recent successes in eliminating chemical weapons in Libya and Syria and new countries acceding to the Chemical Weapons Convention are signs of a strong global commitment to their end. At the same time, others view continual use of chemical weapons in Syria and by the Islamic State as evidence that the taboo against them may be weakening. Regardless of the impact on international norms, it is clear that attacking innocent civilians by conventional and mass casualty weapons is a characteristic of modern warfare that we must continue to account for.

A number of state-based WMD threats remain, including in some cases state-sponsored terrorism that may in time drive WMD risks. North Korea tops the list of state-based WMD threats. It is gaining most attention for its now-regular series of nuclear device and ballistic missile tests. The country’s chemical and biological weapons programs present little-understood but worrisome challenges as well.

For the future, it will be prudent for the international community to assume that several current trends will sustain. One is that WMD-related tactics, production and dissemination capabilities, and networks will continually evolve. For example, once denuded of sarin and other military-grade chemical weapons, the regime of Bashar al-Assad switched to common chemicals such as chlorine to continue its slaughter of the Syrian people.

Likewise, it is a safe assumption that the international system of laws and norms to reduce WMD threats is likely to continue experiencing signs of both strengthening and weakening. The years 2015 and 2016 have shown this duality starkly with these systems being successfully leveraged to walk back Iran’s nuclear weapons ambitions, yet being violated with increasing regularity by Kim Jong Un advancing North Korean nuclear weapons capabilities. And as ratification of the Chemical Weapons Convention approaches universality, the above-mentioned evolutions in chemical weapons threats have some in the international community questioning whether new, different tools would be more effective than the existing treaty system.[1]

While some specific characteristics of WMD threats will continue to change, many common lessons from historical efforts to reduce these threats remain relevant for present and future challenges.

[1] Oliver Meier and Ralf Trapp, “Russia’s chemical terrorism proposal: Red herring or useful tool?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, June 7, 2016, http://thebulletin.org/russia%E2%80%99s-chemical-terrorism-proposal-red-herring-or-useful-tool9531

3. Kazakhstan’s Efforts Against WMD

Not long after independence, Kazakhstan chose to give up the nuclear weapons and related components it had inherited. Nazarbayev decided in 1992 to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and agreed that Kazakhstan would live up to its part of the nuclear commitments made between the United States and the Soviet Union. After multiple engagements with U.S. President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker, on May 19 he wrote to President Bush to confirm, “Kazakhstan guarantees the carrying out of the elimination of all kinds of nuclear weapons, including strategic offensive weapons, located on its territory, over a period of seven years in accordance with the START treaty.”[1] By April 1995 Kazakhstan completed the process of sending all of its more than 1,400 nuclear warheads, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and other nuclear weapons-related equipment back to Russia, and finished dismantling seven heavy bombers that remained in its territory by the following year.[2] One decade later, Kazakhstan joined its neighbors in creating a nuclear weapons-free zone for Central Asia.

Throughout this time, Kazakhstan conducted a number of specific projects and programs to reduce legacy WMD threats and address new, emerging WMD challenges. It has also engaged in a number of efforts to leverage these projects in shaping international agreements and norms. These activities hold important lessons for current WMD threats, and show that through national commitment and international partnerships, even newly-independent and economically stressed countries can successfully juggle multiple major countering-WMD missions simultaneously.

Project Sapphire

Project Sapphire, a mission to remove extremely dangerous nuclear materials from Kazakhstan, was conducted quietly in 1994 and extensively detailed by David Hoffman in his 2010 Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Dead Hand. In late 1993, one of us (Weber) served at the U.S. Embassy in Kazakhstan and was approached by individuals offering to sell about 600 kilograms of highly enriched uranium to the U.S. government.

By March 1994, the government of Kazakhstan permitted U.S. experts to visit the Ulba Metallurgical Plant in Ust-Kamenogorsk in eastern Kazakhstan, where the uranium was then stored, in order to collect samples. On-site analysis and later testing at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee confirmed what Kazakhstani sources had indicated: the uranium was enriched to a weapons grade, with around 90% uranium-235 present in all of the samples.[3] After months of little action, confirmation by the U.S. experts that the uranium was highly enriched, that it was in sufficient quantity for dozens of nuclear bombs, and that it was weakly secured triggered agreement to work with Kazakhstan on solutions. A small team of representatives from the relevant U.S. agencies was created to conduct this work while keeping it secret.

Those knowledgeable of the highly enriched uranium at Ulba considered various options. Some accounts indicate that Kazakhstani officials initially considered upgrading the site’s security in order to keep the material in place, possibly without the involvement of the international community. Between Nazarbayev’s desire to show his country’s commitment to responsible nonproliferation measures and uncertainties regarding the material due to lack of information from Russia, Kazakhstan’s preference was to explore options for its removal.

The U.S. team assigned to explore solutions first considered three main options: doing nothing, securing the materials in place and upgrading protection, control, and accounting capabilities at the Ulba plant, and removing it. William Potter, who wrote one of the earliest histories of Project Sapphire, noted that some at the Department of Energy favored a “Russian solution” to assisting Kazakhstan.[4] Another account summarizes the debate succinctly:

“The team initially considered keeping the material where it was, only with tighter security. This option was quickly rejected because of the huge investment required to beef up security at Ulba. This step would also have required routine infusions of upkeep money because the Kazakhs simply could not afford to pay the high price for it. Besides, Mr. [Jeff] Starr noted, ‘there would always be some [US] uncertainty about how secure it was.”[5]

Instead, Nazarbayev and U.S. President Bill Clinton authorized a plan to secretly airlift the material to the Oak Ridge Y-12 plant for downblending. The technical experts read into the challenge began developing operational details while others handled bureaucratic, legal, and political details. In what would become a common issue across the history of WMD removal operations, one major challenge was that the highly enriched uranium was not stored in containers or by methods that were compliant with IAEA requirements or international shipping standards. Those involved also wrestled with the question of whether or not to speak with officials in Moscow, given that the nuclear materials were originally Soviet-owned.[6] Another challenge was resistance in Tennessee to bringing in Kazakhstan’s nuclear materials. The latter two challenges required elevation to high-level political leadership, and U.S. Vice President Al Gore assisted with overcoming both.[7]

Another question was how to pay for the operation. Then-Senators Richard Lugar and Sam Nunn sponsored the legislation that formed the U.S. Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program in 1991 with the goal of addressing WMD threats emanating from the breakup of the Soviet Union. The program’s designers and leaders originally envisioned its work would focus mostly on ridding the region of nuclear weapons, components, and infrastructure, and in doing so contribute to implementing bilateral U.S.-Soviet agreements to reduce nuclear arsenals from their Cold War heights. Though it would take on a very different character, Project Sapphire fit within the legal limits of CTR, and the interagency team agreed that it was the most appropriate option for the majority of U.S. costs and financial contributions related to the operation. Luckily, the United States and Kazakhstan had already finalized the general legal agreement to allow bilateral CTR work during Vice President Al Gore’s visit to Almaty in December 1993, just months before U.S. experts confirmed the extent of the risk inherent in the highly enriched uranium housed at the Ulba site.

Once the operation began in October 1994, the removal process took about one month on the ground. Weather, minimal pre-trip training for some of its personnel, and poor secure communications capabilities were among the challenges encountered during the operation. Keeping an accurate inventory, repackaging, and properly labeling the nuclear materials required meticulous work, during which the team found several canisters of highly enriched uranium not included in the original inventory. Kazakhstani and U.S. officials navigated these and other issues without compromising the project’s success.[8]

Project Sapphire became an early and high-payoff experiment. It proved that physically removing dangerous materials for disposal in a safe location could be a viable WMD threat reduction option. The generally good working relationship with Kazakhstan, which would continue to strengthen over time, proved the benefits of the conducting this type of sensitive threat-mitigation work quietly and cooperatively among countries.

The work of Project Sapphire became the CTR program’s first major nuclear materials security effort, and provided a public communications success story for Kazakhstan and the United States. Just a few years after independence, Kazakhstan had a tangible and important international security success under its belt. Ambassadors from both countries and three U.S. cabinet secretaries held a press conference on November 24, 1994, one day after the completion of the main project and just before the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday. Secretary of Defense William Perry succinctly summarized: “Both the United States and Kazakhstan had serious concerns about the security of the material. Now it is secure. There is no better example of how the Nunn/Lugar program can help eliminate the national security threat before it arises.”[9]

Degelen

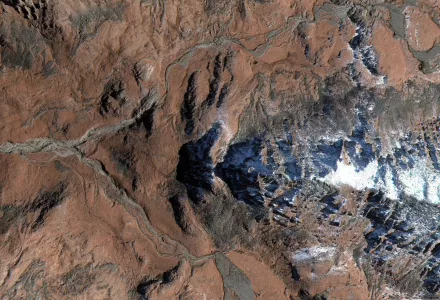

Quiet trilateral cooperation from 1996 to 2012 among the United States, Kazakhstan, and Russia enhanced security and surveillance and sealed off boreholes, tunnels, and other infrastructure previously used by the Soviets for nuclear tests at the Semipalatinsk nuclear weapons test site. Eben Harrell and David Hoffman first detailed this work, now referred to as the Degelen Mountain project after one area of the site where many underground tests were conducted, in a 2013 monograph. As they described, “Between 1991 and 2012, scavengers looking for valuable scrap metal and equipment from the former Soviet test site came within yards of the unguarded fissile material.”[10] The three countries, over more than 16 years, worked together to prevent further access to this dangerous treasure.

In the early 1990s, when focus regarding the newly-independent Kazakhstan tended to be directed at removing its legacy Soviet nuclear weapons and related heavy military equipment, Kazakhstani and U.S. leaders used the Nunn-Lugar CTR program as a mechanism for experts from both countries to assess conditions at the Degelen site and begin the process of sealing its tunnels and access points. Along with Project Sapphire, this showed the flexibility of the CTR program, which was once again used to address a new type WMD risk that did not involve weapons themselves. It also provided further evidence that the program could facilitate quick action, when the first tunnel was sealed less than six months after the work agreement was settled.[11]

The first phases of this work were publicized, and served as early evidence of Kazakhstan’s commitment to nonproliferation. Kazakhstan’s leaders even agreed to use the site for data collection regarding underground explosions as an early contribution to the new Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which the United Nations opened for signature in September 1996. Kazakhstan allowed three massive conventional explosions within its test tunnels, which offered a unique opportunity for monitoring stations around the world to gather data on the signatures of conventional underground detonations. These could be compared to data from past U.S. and Russian underground nuclear tests, and natural events such as earthquakes, to improve the world’s ability to characterize future nuclear tests. For one of these detonations, Kazakhstan even welcomed reporters to the site.[12]

Within a few years, however, a small group of American scientists became alarmed that weapons-usable materials may still be recoverable if the tunnels were broken into, and that additional, unsecured materials may be located in then-unknown locations at the site. By the end of the 1990s and dawn of the new century, quiet dialogue and survey work among U.S., Kazakhstani, and Russian experts began to raise new details about Soviet-era experiments. Throughout this decade, scavengers continued to extract metal and equipment parts, and herders continued to roam the areas around the former nuclear test site.

The tri-national experts decided to secure most of the site’s nuclear materials, and provided much-improved security and surveillance around the site. One obstacle to removing the nuclear materials included legal and regulatory hurdles related to moving the materials back to Russia, depending on how the materials were categorized based on composition, quantity, and other factors. Another perpetual hurdle was Russian suspicion that too much U.S. handling of the materials and knowledge gained about their composition could be used to learn classified details of Russia’s nuclear weapons program. Removal operations could also be costlier, and risked igniting ever-present fears regarding the area’s environmental contamination.[13]

The full scale of the Degelen project was only revealed to the public by Presidents Obama, Nazarbayev, and Medvedev at the 2012 Nuclear Security Summit in Seoul. According to Harrell and Hoffman, Kazakhstan, Russia, and the United States agreed that the operations conducted in the 2000s should remain secret—including from the IAEA—in order to keep the nuclear materials secure. Informing the public about the ongoing operation, which would amount to showing terrorists or black marketeers where they could obtain usable nuclear materials, seemed out of the question.[14] While some personal accounts indicate that select IAEA officials were kept informally in the loop, the IAEA’s contemporaneous work at the site was largely limited to its assistance to the government of Kazakhstan in assessing potential radiological contamination risks.[15]

Approaches to Countering WMD Threats

|

Approach |

Examples from Kazakhstan |

|---|---|

|

Removing WMD materials for offsite storage or destruction |

Project Sapphire Degelen Mountain Project Aktau |

|

Dismantling facilities and equipment |

Stepnogorsk |

|

Engaging and employing scientists and other experts |

Degelen Mountain Project Stepnogorsk Aktau Central Reference Laboratory International Science and Technology Center |

|

Materials consolidation and secure storage |

Central Reference Laboratory Aktau |

|

Improving security and safety strategies, standards, training, and practices |

Degelen Mountain Project Stepnogorsk Aktau Central Reference Laboratory Global Health Security Agenda |

Table 1: Kazakhstan has cooperated with international partners to employ a range of approaches to reduce weapons of mass destruction threats. This table highlights examples of specific projects that used several methods during the country’s first 25 years of independence. In many cases, Kazakhstan’s WMD threat reduction projects used multiple approaches simultaneously or in succession.

Aktau

Along the Caspian Sea, in late 1991, the newly-independent Kazakhstan became the owner of a BN-350 fast breeder reactor. The Soviet Union began operating the reactor in 1974 to supply electricity, desalinate water, and produce plutonium for its nuclear weapons.

The site, in a port town Kazakhstan now calls Aktau, held 10 metric tons of highly enriched uranium and 3 metric tons of weapons-usable plutonium, one of the largest stockpiles of the latter anywhere in the world. This was enough material to make 775 nuclear weapons, held at a site accessible by boat from Iran, Dagestan, and other areas of concern.[16]

Kazakhstan, working with the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration and National Labs, the United Kingdom, the IAEA and other partners, began in 1997 to move the dangerous nuclear materials from Aktau to secure, long-term storage. The first step was to consolidate the highly enriched uranium and plutonium into large casks made of steel and concrete. The size and weight of these 61 casks, which weighed 100 tons each, would make it extremely difficult for unauthorized actors to move or access the materials. Until they were to be moved, the casks stood on a temporary concrete pad that was well secured and monitored. Later, Kazakhstan transported the material across 1,860 miles, covered in part by train and in part by trucks. Kazakhstani and U.S. experts conducted vulnerability studies to mitigate the risks of this movement, which took 12 shipments over the course of one year. As with Project Sapphire, weather was a challenge at times. At one point, extreme flooding near the Kurchatov Rail Transfer Site, which had to be specially constructed to move the casks from rail cars to the trucks, threatened progress.

A 1998 Philadelphia Inquirer article described this work well in part of its headline: “The Operation will be Complex.”[17] Completed in November 2010, it required extensive logistical and security planning, the procurement of communications and surveillance systems, conduct of a dry run of the transport, and IAEA monitoring throughout. It required building multiple facilities and storage sites, and expanding the rail infrastructure to be used in moving the materials. After the project’s completion, longtime National Nuclear Security Administration official Anne Harrington described other challenges encountered: “Preparing a decommissioning plan, decontaminating the primary sodium coolant, and forming the process and design for the final waste from the sodium processing operations were all major scientific challenges that required teamwork and cutting edge ideas to complete.”[18] Kazakhstani, U.S., and international scientists and technical advisors collaborated on research projects and the development of technical solutions to overcome these types of issues.

As this project progressed over more than a decade, another successful effort focused on removing and blending down additional highly enriched uranium left at Aktau. Between 2001 and 2005, this project involved a partnership between Kazakhstan and the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), a U.S.-based nonprofit organization that contributes to global nonproliferation work. Aside from the material described above, Aktau held 2,900 kilograms of fuel enriched up to 26 percent that then-Vice President of NTI Laura Holgate described as “falling through the cracks’’ of the larger project.[19]

Kazakhstan and NTI agreed to co-fund moving this uranium from Aktau to the Ulba Metallurgical Plant by rail and blending it down to an enrichment level of use only for civilian purposes. The project included upgrades to allow Ulba to securely store and convert weapons-grade nuclear materials, capacities that Kazakhstan has maintained in the hope of contributing to future global efforts to do the same. This successful example of a public-private partnership involved the IAEA and kept U.S. government agencies informed.[20]

Stepnogorsk

The Soviet biological weapons programs extended back to the 1920s and included various lines of effort that focused on diseases to affect humans, plants, and livestock. After the country acceded to the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention in the 1970s, some of its biological weapons work moved under the guise of civilian facilities. A now-declassified 1992 U.S. memo describes this and other details of the Soviet bioweapons program:

“As regards specific agents, our information shows that the former USSR’s biological weapons program—using military and civilian facilities—has explored the development of almost all types of Biological Weapons agents, including infectious organisms, toxins, venoms, and bioregulators. The list includes, among others, those agents causing plague, anthrax, cholera, smallpox, and various hemorrhagic fevers and rickettsial diseases...It is clear from our evidence that much of the genetic engineering work has focused on creating new Biological Weapons agents with increased toxicity and lethality which also may defeat defensive countermeasures.”[21]

The Scientific Experimental and Production Base facilities in the once-secret closed city of Stepnogorsk, Kazakhstan, were among these sites. It once employed hundreds of scientists to work on anthrax, staphylococcus toxin, and Ebola-based weapons, among other civilian and military activities. Ken Alibek, a former senior leader of the Soviet biological weapons program who emigrated to the United States in 1992, wrote that his job at Stepnogorsk “was, in effect, to create the world’s most efficient assembly line for the mass production of weaponized anthrax.”[22] Across about 25 buildings, the site housed equipment built and proven for large-scale, wartime mobilization production of agents for biological weapons — more than 300 metric tons of anthrax in about 10 months. The site housed giant fermentors, centrifuges, explosive aerosol testing chambers, biocontainment systems, and countless other types of equipment.

After the Soviet Union fell, Kazakhstan was left with the important task of ensuring Stepnogorsk and other remnants of the Soviet biological weapons infrastructure could no longer be used for nefarious purposes. Early in this process, officials considered a plan mostly focused on converting them for civilian purposes in order to take advantage of the existing infrastructure and to provide jobs for any remaining scientists and experts who might otherwise use their dual-use knowledge to benefit global actors seeking to develop biological weapons. The conversion approach was selected not just for Stepnogorsk, but also for other sites around Kazakhstan where formerly military communications, electronics, manufacturing, and other facilities might be alterable for civilian purposes.

This plan soon met significant hurdles. The government of Kazakhstan initially structured the site under a newly formed joint stock company, AO Biomedpreparat, and tried to fund the conversion to civilian work such as vaccine, biopesticide, and insulin production. Several challenges combined to drive prohibitively high operating costs. The U.S. government stepped in with assistance that would contribute to developing a public-private partnership to carry out conversion work at Stepnogorsk and several other sites. This likewise foundered due to infrastructure issues, high costs, divergent visions among the players, and other hurdles. Soon officials from Kazakhstan and the United States were considering options for more limited conversion plans, to include dismantlement of the remaining equipment that had been installed for military purposes. By the mid-90s, the U.S. Congress passed legislation halting American government funding for defense conversion work.[23]

This change of plans was not unanimous nor smooth. Reports from bilateral discussions in this period show that some experts and officials in Kazakhstan disagreed with U.S. advice to proceed with destruction rather than conversion for much of the site’s equipment and facilities. However, President Nazarbayev decided to permit the dismantlement option for the former bioweapons facilities and equipment in order to telegraph his country’s compliance with treaty commitments.[24] Though many of its facilities would be destroyed, a “Stepnogorsk Initiative” working group with personnel from various U.S. agencies was formed to continue developing ideas for future uses of the site and its personnel.

In Kazakhstan, initial work to prepare for dismantlement operations, including installation of an environmental monitoring system and inventory activities, began in 1998. The dismantlement process began the following year. Scholars Sonia Ben Ouagrham and Kathleen M. Vogel created an extensive account of the hurdles the project team had to overcome to complete their work:

“[I]n building 231, dismantling the large drying machines proved challenging; one dryer weighed over 200 tons. Since this equipment had to be removed from the building, Biomedpreparat [which then ran Stepnogorsk] needed to acquire specialized lifting devices and cranes. Perhaps more significant, portions of the dismantlement work were carried out during the winter months where the temperature frequently dropped to -30/C. The buildings had been without electricity, heating, and water for five years and many pieces of equipment used for the dismantlement would freeze at -20/C. Electrical shortages, freezing of disinfectants, and poor ventilation conditions were also problematic during the winter months. For example, the power station that provided the facility with electricity was only intermittently in service. Appropriate physical protection of workers was also a major issue. Special equipment and clothing that could simultaneously protect workers from hazardous materials and keep them warm were needed. Since the facility was located outside of the Stepnogorsk city limits, worker transport to and from the dismantlement area was another problem, especially in winter with snow and poor road conditions.”[25]

The on-site team worked through these issues by bringing in additional power sources and monitoring equipment, installing areas for personnel to eat and shower, and other troubleshooting. The majority of dismantlement work took around one year to complete.

Many in Kazakhstan believed the site’s remaining equipment that had not been used in relation to bioweapons could still be used for civilian purposes. However, long-term financing for civilian biomedical and biotech work and employment of remaining local scientists proved to be a substantial challenge, at times for mundane reasons. The relatively remote location and harsh winter climate of Stepnogorsk meant that supplying energy to the site was expensive. This and other high operating costs would affect the commercial viability of the medical, energy, and agricultural products and services that some in Kazakhstan still wished to produce.[26] Still, into the 2000s, once the dismantlement of Stepnogorsk’s bioweapons facilities stood as a historical WMD threat reduction success, Kazakhstan shifted much focus to new approaches as global concerns regarding biological threats evolved.

Global Health Security and the Central Reference Laboratory

Several issues merged that pushed Kazakhstan’s work to address biological threats into new forms in recent years. One challenge was that by the early 2000s, many of Kazakhstan’s Soviet-era biological sciences, research, and development facilities were in need of upgrading, and stood to benefit from upgrades and new structures meant to withstand greater seismic activity. Second, successful terrorist attacks in Africa, the Middle East, the United States, South Asia, and elsewhere since the mid-1990s forced most countries to prioritize efforts to counter non-state threats. Kazakhstan’s approaches shifted along with those of its cooperative partners, in particular due to active terrorist networks declaring interest in WMD, the United States increasing attention to mitigating bioterrorism risks based on the use of anthrax in lone-actor attacks against the American people, and other indicators.

Coinciding with the emergence of major terrorist threats and Kazakhstan’s need to upgrade, outbreaks such as Ebola, pandemic influenzas, SARS, and others have convinced many countries to invest more significant resources in preventing, detecting, and responding to emerging infectious disease threats. As such, Kazakhstan joined more than 50 countries and international organizations in committing to the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) as a framework for addressing both natural and manmade biological threats in a comprehensive manner. Through the GHSA, launched in 2014, participants make concrete commitments to improve their capabilities in 11 actions areas, such as disease surveillance, multisectoral rapid response, workforce development, and biosafety and biosecurity. To improve implementation and accountability of countries’ commitments, it includes processes for countries independently assessing one another’s progress.[27]

Today, Kazakhstan’s work to improve its laboratory systems is considered an early achievement of the still-young GHSA framework. The country identified safety and security deficiencies at some of its laboratories, such as doors without locks, poor signage, and inconsistent implementation of safety practices. Since 2014, the country has drafted a national strategy defining specific roles and standards for its labs, and has started the implementation process.[28] Predating but aligned with the GHSA commitments, Kazakhstan also hosts one of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) six Global Disease Detection Regional Centers, meant to promote early detection of emerging disease outbreaks and facilitate rapid, effective response by Central Asian governments.[29]

One new, key node in Kazakhstan’s lab system is the Central Reference Laboratory (CRL), a state-of-the-art single-health research facility at the Kazakh Scientific Center for Quarantine of Zoonotic Diseases near Almaty that will play an important role in the country living up to its health security and biosecurity commitments. The CRL will allow the country to more quickly diagnose and respond to human and animal outbreaks from plague, cholera, anthrax, and other diseases that are endemic to the region or otherwise high-risk. In 2014, experts at the Congressional Research Service further described the importance of the CRL in Kazakhstan and similar facilities in the region: “As many of the scientists from the Soviet era retire, a new generation of experts will need to step up to manage the public health and biosecurity programs in these states, which have limited resources. In addition, the region around the former Soviet Union has experienced an increase in militant Islamic groups, raising concerns about terrorist access to biological pathogens at facilities in the FSU [Former Soviet Union].”[30]

A particularly important role of the CRL will be consolidating and securing all the country’s biological materials of highest concern for misuse into a single, well-secured facility. Consolidation is itself an important tool for thwarting those interested in developing biological weapons. In many countries, pathogens that could be cultured for nefarious uses are stored in multiple locations, at times with weak or non-existent security measures, little to no monitoring of who accesses specific materials, and inconsistent levels of employee training. Addressing this supply-side risk by ensuring the highest-risk materials are centrally located in one secure location can make it significantly more difficult for bad actors to obtain the means to producing bioweapons. The case of Japanese terrorist group Aum Shinrikyo shows this well. Its members decided to find natural sources rather than purchase starter material for botulinum toxin, which led to the group’s lead biologist working with inferior material. And had the group accessed a strain of bacillus anthracis lethal against humans, rather than the more benign samples they did obtain, its anthrax attack attempts would likely have been successful.[31]

Despite these positive contributions to regional security, the CRL has been the target of Russian propaganda and misinformation, including false claims regarding the utility of the facility for offensive military capabilities.[32] This shows the importance of allowing media and experts access to facilities and their personnel, and continual messaging efforts to reassure the international community of the important public health and threat reduction work conducted at labs such as Kazakhstan’s CRL.

The Nuclear Fuel Bank

In August 2015, Kazakhstan and the IAEA concluded an agreement to host an international fuel bank of low enriched uranium at the Ulba Metallurgical Plant, the same site from which Project Sapphire removed 600 kilograms of highly enriched uranium about 20 years prior. The fuel bank will act as a supplier of last resort for nuclear energy facilities that are unable to obtain fuel from commercial vendors.[33]

The hope for the fuel bank is that it will help to convince countries with civil nuclear power programs that they do not need to develop their own fuel enrichment capacity, nor hold excess supplies of nuclear fuel. It is part of a broader vision of limiting widespread future expansion of global stocks of nuclear materials, and limiting the proliferation of the knowledge and technologies required for nuclear fuel enrichment and reprocessing. The fuel bank may also contribute to the development of regional or fully internationalized models for nuclear energy ventures, which in many cases would increase confidence that specific projects will not contribute to nuclear weapons risks and that they hold high standards of safety and security. This will be increasingly important as nuclear technology export patterns continue to change as new countries host nuclear reactors for the first time and new suppliers emerge as strong players in the civil nuclear marketplace.

International Science and Technology Center

The United States, Japan, the European Union, and the Russian Federation began to form the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC) in 1992 in order to address concerns that former Soviet WMD scientists could be attracted to countries such as Iran that might seek to develop nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons programs. Soon after, the ISTC expanded to include a number of former Soviet states, with Kazakhstan among them. According to a 2014 tally by the U.S. Congressional Research Service, the ISTC has “supported the work of more than 70,000 former weapons scientists” since its inception.[34] This included important contributions to the Aktau project and other efforts described in this report.

Notably, the center has been leveraged many times as a stop-gap when other efforts to employ scientists were halted. For example, the ISTC stepped up to provide work for biological scientists and other workers from Stepnogorsk during gaps between other conversion and elimination projects. It has also perpetuated productive science and technical relationships during times of heightened political and security tensions.

In addition to Kazakhstan benefiting from the ISTC, over the past two decades it has become one of the center’s leaders. Kazakhstan has hosted regular seminars, workshops, and training sessions in recent years, evolving the subjects to issues such as countering illicit trafficking in WMD materials and biosecurity as regional and global threats have shifted.[35] When Russia began backing out of the ISTC in 2014 and indicated that it would no longer host its headquarters, Kazakhstan stood up to be the center’s new host. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe lauded the ISTC in 2015, the first year of its new home in Astana: “The International Science and Technology Center, which is engaging in the initiative to prevent a brain drain from the former Soviet republics in order to ensure nuclear non-proliferation, made a fresh start here at Nazarbayev University this summer. Japan will continue to support this institution’s activities, which have now continued for more than 20 years.”[36]

International Leadership and Norm-Setting

Kazakhstan has shaped its international identity by sharing its domestic and cooperative efforts to stem WMD threats and leveraging its experiences to advocate for the international regimes, norms, and systems that are imperative for reducing proliferation risks.

Its close work with Japan is notable given the unique historical commonalities the countries share. Both have possessed or used WMD—chemical and biological weapons by Japan, and biological and nuclear weapons by Kazakhstan—and the publics of both countries have suffered as victims of WMD testing and use. In recent years, one concrete example is their collaboration on CTBT. A Kazakhstani-Japanese joint chairmanship of the treaty’s Article XIV Conference began in 2015, launching their leadership of a two-year effort to push for entry into force of the CTBT. This process will require ratification by the eight remaining countries that participated in the initial CTBT negotiations and were nuclear-capable when negotiations concluded in 1996. The remaining countries are the United States, China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Pakistan, and North Korea.[37] Japan and Kazakhstan have used their CTBT chairmanship platform not only to push for ratification, but to exert moral authority in pressuring countries to make stronger commitments against proliferation and to condemn North Korea’s nuclear tests.

More broadly, the government of Kazakhstan is now playing an important role in promoting comprehensive approaches to interrelated global issues. For example, Kazakhstan’s fuel bank vision is intended to keep its energy and nonproliferation goals in synch. The histories surrounding Semipalatinsk and other WMD testing and production sites around Kazakhstan are tales of intertwined proliferation, environmental, and public health concerns. The country extended this into its international activities by selecting the interrelated issues of nuclear security, energy security, food security, and water security as the four policy priorities of its bid for one of the non-permanent UN Security Council seats for 2017-2018.[38] This bid was successful, likely aided by Kazakhstan’s CTBT leadership with Japan and aid to the negotiations that led to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. Work to address any of Kazakhstan’s issue priorities independently could undermine progress among the others. At the same time, all countries can maximize their investments by developing policies that are mindful of addressing multiple global risks in tandem. Nazarbayev described this succinctly in a 2015 Foreign Policy article:

“On the one hand, in the majority of states, especially in the developing world, there is a growing demand for energy to support economic growth and improve living standards. On the other hand, concerns about climate change and carbon emissions demand new approaches to energy. Only atomic energy can address both concerns, which is why its use will rapidly expand in the near future. Already, hundreds of nuclear power plants are in the construction or planning phases worldwide. The rapid expansion in nuclear energy, however, brings along proliferation risks.”[39]

By articulating the nexus of these issues and through its continual presence in international and regional security fora, Kazakhstan continues to leverage its unique national experiences with WMD for the benefit of mitigating future threats around the world.

|

Lessons from Kazakhstan’s History |

|

Think beyond the weapons Compare various threat reduction options early Be agile Ensure consistent leadership Find international, cooperative approaches whenever possible Have a public communications strategy Foster cooperation among scientific and technical experts |

[1] Letter from President Nazarbayev to President Bush on START, provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB447/1992-05-19%20Letter%20from%20President%20Nazarbayev%20to%20President%20Bush.PDF; and Joseph P. Harahan, With Courage and Persistence: Eliminating and Securing Weapons of Mass Destruction with the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Programs, (Defense Threat Reduction Agency: DTRA History Series, 2014), pages 186-7.

[2] Hans M. Kristensen, Alicia Godsberg, Steven Aftergood, and Jonathan Garbose, “Kazakhstan Special Weapons,” Federation of American Scientists, http://fas.org/nuke/guide/kazakhstan/

[3] E.H. Gift, “Analysis of HEU Samples from the Ulba Metallurgical Plant,” Oak Ridge National Security Program Office, Initially Issued July 1994, http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB491/docs/12%20-%20US%20report%20on%20Ulba%20uranium%20assay.pdf

[4] William C. Potter, “Project Sapphire: U.S.-Kazakhstan Cooperation for Nonproliferation,” in John Shields and William Potter, eds., Dismantling the Cold War: US. and NIS Perspectives on the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, 199&): pages 351-2.

[5] Starr led the small, ad hoc U.S. team. John A. Tirpak, “Project Sapphire,” Air Force Magazine, August 1995. Provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB491/docs/15%20-%20Air%20Force%20Journal%20account.pdf

[6] U.S. Vice President Al Gore spoke with the Russian prime minister, who approved of the concept of removing the highly enriched uranium for disposition in the United States.

[7] Potter, pages 350-55.

[8] Defense Threat Reduction Agency, “Project Sapphire After Action Report,” November 1994. Provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB491/docs/01%20-%20After%20Action%20report%20DTRA.pdf. See also Harahan, pages 189-192, and Potter, pages 355-7.

[9] U.S. Department of Defense, “Transcript of press conference by Defense Secretary William Perry, Secretary of State Warren Christopher and Energy Secretary Hazel O’Leary on Project Sapphire,” November 23, 1994. Provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB491/docs/14%20-%20Defensegov%20Transcript%20DoD%20News%20Briefing%20Secretary%20of%20Defense%20William%20J%20Perry%20et%20al%2011%2023%2094.pdf

[10] Eben Harrell and David E. Hoffman, “Plutonium mountain: Inside the 17-year mission to secure a dangerous legacy of Soviet nuclear testing,” (Cambridge, Mass.: The Project on Managing the Atom, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University, August 2013), page 1.

[11] Harahan, pages 196-7.

[12] Judith Miller, “One Last Explosion At Kazakh Test Site To Aid Arms Treaty,” The New York Times, September 25, 1999; Harahan, pages 193-199.

[13] Harrell and Hoffman.

[14] Harrell and Hoffman, pages 2 and 19.

[15] International Atomic Energy Agency, “The Semipalatinsk Test Site, Kazakhstan: Radiological Conditions at the Test Site: Preliminary assessment and recommendations for further study,” last updated December 9, 2014, http://www-ns.iaea.org/appraisals/semipalatinsk.asp

[16] National Nuclear Security Administration, “NNSA Secures 775 Nuclear Weapons Worth of Weapons-Grade Nuclear Material from BN-350 Fast Reactor in Kazakhstan,” November 18, 2010, https://nnsa.energy.gov/mediaroom/pressreleases/bn35011.18.10; “Sandia security experts help Kazakhstan safely transport, store Soviet-era bomb materials,” Sandia Labs News Releases, February 8, 2011, https://share.sandia.gov/news/resources/news_releases/aktau-reactor/#.V-mR9k0rIes

[17] Steve Goldstein, “U.S. to Move Plutonium at Site Near Iran; The Weapons-Usable Cache is from an Old Soviet Reactor in Kzakhstan; The Operation will be Compled,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 6, 1998.

[18] National Nuclear Security Administration, “Deputy Administrator Anne Harrington on Completion of BN-350 Fuel Shipments, November 18, 2010, http://nnsa.energy.gov/mediaroom/speeches/harringtonbn350

[19] Ethan Wilensky-Lanford, ‘Kazakhstan Says End of Bomb-Grade Uranium Is in Sight,” The New York Times, October 9, 2005.

[20] NTI, “Kazakhstan and NTI Mark Success of HEU Blend-Down Project; Material Could Have Been To Make Up To Two Dozen Nuclear Bombs,” October 8, 2005, http://www.nti.org/newsroom/news/kazakhstan-and-nti-mark-success-heu-blend-down-project-material-could-have-been-make-two-dozen-nuclear-bombs/

[21] U.S. Department of State, “Talking Points for Under Secretary of Defense Frank Wisner for Meetings in Moscow on the Soviet Biological Weapons Program,” National Security Archive, September 17, 1992, http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB61/Sverd32.pdf

[22] Ken Alibek and Stephen Handelman, Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World--Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran It, (New York: Random House, 1999), page 88.

[23] Gulbarshyn Bozheyeva, Yerlan Kunakbayev, and Dastan Yeleukenov, “Former Soviet Biological Weapons Facilities in Kazakhstan: Past, Present, and Future,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, June 1999, http://www.nonproliferation.org/former-soviet-biological-weapons-facilities-in-kazakhstan/; and Vogel, pages 33-40.

[24] Roger Roffey and Kristina S. Westerdahl, “Conversion of former biological weapons facilities in Kazakhstan. A visit to Stepnogorsk, July 2000,” Swedish Defense Research Agency Report, May 2001 Provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NunnLugar/2015/53.%202001-05-00%20Conversion%20of%20former%20biological%20weapons%20facilities%20in%20Kazakhstan.A%20visit%20to%20Stepnogorsk.pdf; Sonia Ben Ouagrham and Kathleen M. Vogel, “Conversion at Stepnogorsk: What the Future Holds for Former Bioweapons Facilities,” Cornell University Peace Studies Program Occasional Paper #28, February 2003.

[25] Ouagrham and Vogel, pages 40-41.

[26] Ouagrham and Vogel; Alima Bissenova, “Germ Weapons Plant Is Dismantled,” Associated Press, November 1, 2001.

[27] See the Global Health Security Agenda website at https://ghsagenda.org/index.html

[28] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Kazakhstan: Improving Laboratories One Step at a Time,” February 10, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/stories/kazakhstan-improving-labs.html

[29] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Global Disease Detection Program: Kazakhstan and Central Asia,” April 4, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/gdd/kazakhstan.htm

[30] Mary Beth D. Nikitin and Amy F. Woolf, “The Evolution of Cooperative Threat Reduction: Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, June 13, 2014, page 39, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/nuke/R43143.pdf; Alex Pasternack, “Why the U.S. is BUilding a High-Tech Bubonic Plague Lab in Kazakhstan,” Popular Science, August 29, 2013, http://www.popsci.com/technology/article/2013-08/why-us-building-high-tech-bubonic-plague-lab-kazakhstan

[31] Richard Danzig, Marc Sageman, Terrance Leighton, Lloyd Hough, Hidemi Yuki, Rui Kotani and Zachary M. Hosford, “Aum Shinrikyo: Insights Into How Terrorists Develop Biological and Chemical Weapons,” Center for a New American Security, July 2011, http://www.cnas.org/files/documents/publications/CNAS_AumShinrikyo_Danzig_0.pdf

[32] For example, “Former Kazakhstan MoD Tugusov suspects new laboratory has military purpose,” BioPrepWatch Reports, January 28, 2014.

[33] International Atomic Energy Agency, “The IAEA LEU Bank,” https://www.iaea.org/ourwork/leubank; Kairat Umarov, “Letter from Kazakhstan: Why we believe in the nuclear fuel bank,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 27, 2015, http://thebulletin.org/letter-kazakhstan-why-we-believe-nuclear-fuel-bank8687

[34] Mary Beth D. Nikitin and Amy F. Woolf, “The Evolution of Cooperative Threat Reduction: Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, June 13, 2014, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/nuke/R43143.pdf

[35] NTI, “International Science and Technology Center,” last updated July 13, 2016, http://www.nti.org/learn/treaties-and-regimes/international-science-and-technology-center-istc/

[36] Kantei of the Government of Japan, “Policy Speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Kazakhstan,” October 27, 2015, http://japan.kantei.go.jp/97_abe/statement/201510/1213894_9930.html

[37] Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization,” Japan and Kazakhstan to Spearhead Efforts for Banning Nuclear Testing,” https://www.ctbto.org/press-centre/highlights/2015/japan-and-kazakhstan-to-spearhead-efforts-for-banning-nuclear-testing/, and “Prime Minister of Japan & President of Kazakhstan Adopt Joint Statement on the CTBT,” October 27, 2015, https://www.ctbto.org/press-centre/highlights/2015/prime-minister-of-japan-president-of-kazakhstan-adopt-joint-statement-on-the-ctbt/

[38] Kazakhstan also exerts leadership across these issue areas through its continued support for international institutions such as the International Atomic Energy Agency and World Health Organization that conduct work in nuclear security, energy, climate, health, food, and other related areas.

[39] Nursultan Nazarbayev, “A Step Toward a Safer Atom,” Foreign Policy, September 3, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/09/03/a-step-toward-a-safer-atom-low-enriched-uranium-bank-iaea/

4. Lessons

Several lessons emanate from these cases. First, the hard work of reducing WMD risks extends far beyond just reducing the presence of weapons themselves. Eliminating WMD threats requires the political will and resources to secure dangerous materials, destroy infrastructure capable of producing WMD, and find employment unrelated to weapons for those with dual-use expertise. Kazakhstan and the international community could have easily focused their sole attention on getting rid of the country’s nuclear weapons in the early 1990s and downplayed other WMD risks as domestic concerns. It is to the credit of a relatively small number of experts that attention and resources were dedicated to keeping tons of non-weaponized highly enriched uranium, plutonium, and other WMD-relevant materials off the market, and to ensuring that biological weapons production facilities would not be used for nefarious purposes again.

Second, WMD threat reduction options should be weighed early, and socialized with other players who will shape decisions as operations are planned and conducted. Based on Kazakhstan’s projects, it would be prudent in considering future missions to analyze in detail the costs and benefits of the full range of disposition options early. For Stepnogorsk, shifting plans from converting former biological weapons facilities to destroying much of its equipment and facilities caused friction and delayed progress. Plans always change in the course of operations to secure or eliminate WMD materials and equipment, but thinking through challenges early based on historical examples can help reduce tensions and lags if plans are later implemented.

Third, countering WMD threats, in general, requires agility. Work must be managed in sometimes-restrictive timelines and hurdles will arise, as the Kazakhstan cases show. Those planning this work should ensure they create environments that encourage agility and empower implementers to troubleshoot, and ensure that plans will allow flexibility in navigating changes and surprises as they occur.[1] One method for this revealed by Sapphire and other projects is to develop small teams assigned to advance specific tasks. Such ad hoc groups can be stood up as needed and disbanded when the job is done, and can often help to facilitate rapid decision making and minimize bureaucratic hurdles.

For at least two projects, the Stepnogorsk and Degelen Mountain work, the government of Kazakhstan and its international counterparts showed flexibility when initial plans did not work. For Stepnogorsk, those involved adopted new plans for dismantling and destroying some of the former biological weapons facilities and equipment as challenges to conversion arose. The ISTC shows an extreme example, with Kazakhstan agreeing to house this important work when Russia pulled out. Practical challenges arise, and teams dedicated to implementing projects to reduce WMD threats have to remain flexible to ensure mundane challenges from factors like bad weather and personnel illnesses don’t become show-stoppers.[2]

Fourth, consistent leadership is critical to facilitating action. From the start, Kazakhstan could have sought to retain some or all of the nuclear weapons left by the Soviets, and according to a memo from U.S. Ambassador Courtney in Almaty to the National Security Council in early 1992, that idea had surfaced.[3] Keeping the weapons could have served as a future deterrent to Russia and elevated Kazakhstan’s influence in the region. President Nazarbayev remained steadfast, however, in his commitment to fulfill START treaty commitments and join the NPT.

Kazakhstan’s work to reduce WMD threats also shows that relationships among senior government leaders matter. As the 1992 elections determined a shift in the presidency in the United States, Kazakhstan sought assurances that its relationship with the U.S. would continue as respectfully and frankly as it had under the Bush administration.[4] President Bush and President-elect Clinton set an example as they worked together for a smooth transition, recognizing the importance of the threat weapons of mass destruction pose to humanity and Kazakhstan’s new but unique role in addressing these threats.

Relations remained strong among senior leaders in Kazakhstan and the United States throughout the 1990s. They remained actively engaged in monitoring the progress of CTR activities throughout their conduct. Both presidents and their cabinet leads closely followed each project from its planning phases, required regular updates, and always discussed recent progress and future CTR cooperation when Nazarbayev visited Washington. Notably, U.S. leadership and regular engagement in the progress of reducing Soviet-era WMD threats included the legislative branch. According to one historian, “In Washington, Kazakhstan’s leaders met with Senators Nunn and Lugar and Congressional leaders. Nunn and Lugar traveled repeatedly to Kazakhstan, going out to projects in the missile fields, meeting with Kazakh workers, and the president and senior ministers in the capitol.”[5]

In turn, U.S. leaders were reassured by regular decisions by their counterparts in Kazakhstan that showed their commitment to nonproliferation was always a central consideration. Throughout Kazakhstan’s major WMD threat reduction projects, President Nazarbayev and his top advisors regularly made key decisions that advanced progress. Project Sapphire, for example, may have never transpired if Nazarbayev did not permit U.S. experts from Oak Ridge to sample the uranium at the Ulba plant, as their confirmation that it was weapons-grade material was necessary to convince U.S. officials to act. His desire to show Kazakhstan’s commitment to the BWC and decision to move forward on dismantling the former bioweapons facilities at Stepnogorsk played a similar, critical role in ensuring progress there. For the U.S. side, vice presidential engagement was required at several junctures to overcome interagency disagreement and persuade other senior leaders at home and abroad for their compliance.

Next, whenever possible, internationalize counter-WMD projects from their inception. Successful operations to reduce WMD threats frequently require cooperative approaches among many countries, and often must address the concerns of multiple countries simultaneously. Perhaps more important, cooperative projects can tap the expertise and technical capabilities of multiple countries while spreading financial and political risk.

Kazakhstan took cooperative routes for many of its WMD threat reduction projects. Nazarbayev could have prevented U.S. assistance regarding the highly enriched uranium left at the Ulba Metallurgical Plant and handled it internally—or tried to hide its presence. Instead, the success of Project Sapphire as a bilateral project built confidence in Kazakhstan’s nonproliferation commitments and in cooperative models like the Nunn-Lugar CTR program. The work at Degelen was improved as relations with Russian technical experts strengthened and more detailed understanding of their past work at the site became known. Contributions by the United Kingdom and other international partners added important political, human, and financial resources to the long, hard work at Aktau. Today, Kazakhstan is consistent in showing that WMD threats require international cooperation, from projects like the nuclear fuel bank to efforts to detect and stem the transnational spread of infectious diseases.

Sixth, public communications need to be considered early and refined often for projects to reduce WMD risks. Kazakhstan and its partners were able to keep many projects, such as Sapphire and Degelen, secret for the majority of their conduct. There are several reasons that we can expect those conducting many future countering-WMD missions will not enjoy the ability to keep their work out of the public eyes. It is therefore important to consider education and outreach strategies from the earliest phases of planning these projects.

The likelihood of public disclosure stems in part from the actors and methods now involved with WMD threats. The tool of terrorism usually requires public disclosure in order to ignite fear and gain concessions. Today, terrorist organizations often take credit for their attacks within hours or days via social media and designated spokespeople. This has moved WMD threats into the public realm in ways that can’t easily be masked, and it is driving a heightened need for world leaders to telegraph action against terrorist threats to the public.

Another reason for this trend is that many efforts to reduce WMD threats are now tailored to the dual-use nature of the materials, equipment, facilities, and personnel involved. Kazakhstan’s CRL has many public health missions in addition to its biosecurity contributions. Strong communications will continue to be required to counter misinformation and ensure the public and neighboring governments support this facility’s work into the future. This is the case for similar projects all over the world. Kazakhstan is likewise careful in consistent public messaging that all of it nuclear work is geared toward its long-held nonproliferation goals.

For much of its most sensitive work, the Degelen project was kept a tightly-guarded secret. However, the prospect of public accountability for the project played an important role in the final years of the project. Work at Degelen was frequently slow and normally halted during winter months until the leaders of Kazakhstan, Russia, and the United States pledged through the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit process to complete the project by the summit’s reconvening in 2012. From this, increased funding and manpower facilitated faster progress.[6]

Finally, all of Kazakhstan’s efforts to counter WMD threats show the benefits of focusing on technical cooperation.[7] Mitigating WMD risks involves inherently thorny political and diplomatic challenges. At times, addressing WMD threats requires countries with tense or outright hostile relationships to work together. Though this work cannot be completely dissociated from political decision making, allowing scientists and technical experts to proceed with quiet cooperation can help ensure that other tensions do not stand in the way of effective WMD threat reduction work. In many cases, technical cooperation can even open the door to new diplomatic opportunities.

The Degelen Mountain project in particular weathered post-Cold War mistrust and tense relations in part due to its participants’ focus on scientific and technical issues rather than political ones. As a new country, in possession of WMD from its birth, Kazakhstani officials and experts who participated in these projects faced skepticism and suspicion from some parts of the international community—including some officials in the United States and Russia. The experts conducting the project also weathered varying levels of political tension and, at times, direct hostility between the United States and Russia. This kind of technical cooperation will also need to be intrinsic to threat reduction operations in order to employ scientists and other experts with potentially-dangerous dual-use knowledge and experience.

[1] See also Andy Weber and Christine L. Parthemore, “Innovation in Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction,” Arms Control Today, July/August 2015, https://www.armscontrol.org/ACT/2015_0708/Features/Innovation-in-Countering-Weapons-of-Mass-Destruction

[2] Similarly, agility in developing new plans as new hurdles arise has been required in efforts to destroy chemical weapons from the Syrian and U.S. stockpiles, among other examples. Parthemore, pages 90-91.

[3] National Security Council Memorandum, “Defining American Interests in Kazakhstan,” February 18, 1992. Provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB491/docs/04%20-%201992-02-18%20Cable,%20American%20Embassy%20Alma%20Ata%20Defining%20American%20Interests%20in%20Kazakhstan.pdf

[4] U.S. Department of State, Cable on “Codel Nunn/Lugar Meeting with with Kazakhstan President Nazarbayev,” November 21, 1992. Provided by the National Security Archive at http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NunnLugar/2015/40.%201992-11-23%20Codel%20Nunn-Lugar%20Meeting%20with%20Nazarbayev%20on%20Nov%2021.pdf

[5] Harahan, page 209.

[6] Harrell and Hoffman (2013), page 33.

[7] In their early analysis of CTR cooperation, Shields and Potter note the importance of this cooperation being true collaborative partnerships, and not viewed as donor-recipient assistance projects. Pages 395-6.

5. Recommendations

Several specific recommendations stem from these lessons. First and foremost, we must continue to mine past examples to help plan early for future WMD threat reduction operations. The history of the elimination of Kazakhstan’s Cold War-era, industrial-scale WMD programs continues to offer important insights. Perhaps nowhere is this history more applicable than for North Korea.

Significant work must go toward considering the potential contours of future elimination under wartime or peacetime conditions of North Korea’s WMD infrastructure, including the security, destruction, or conversion of all buildings, equipment, and test sites along with the employment of knowledgeable personnel. As one of us (Parthemore) described in The Nonproliferation Review in 2016:

“Estimates among public sources generally agree that North Korea holds at least 2,500 tons of chemical materials, and may hold up to 5,000 tons or more. Public estimates also generally agree that the composition may include various nerve agents, dual-use chemicals such as chlorine, and many precursors. Some public sources also indicate North Korea’s possible possession of blister agents. As the Nuclear Threat Initiative assesses from multiple sources, ‘North Korea is believed to be capable of deploying its stockpile of chemical agents through a variety of means, including field artillery, multiple rocket launchers, FROG [unguided, or “free rocket over ground,”] rockets, Scud and Nodong missiles, aircraft and unconventional means.’

It is clear from these various estimates that there is no single technical option for eliminating North Korea’s suspected chemical weapons program, but that the task would require, at a minimum, various technologies to neutralize or incinerate bulk chemicals and precursors (or both), and disable, drain, and dispose of various types of delivery mechanisms. The actual size and composition of the stockpile, the age and condition of these materials, types of delivery systems, to what degree North Korea’s chemicals are filled into these systems or stored in bulk, and other factors shape the suite of technologies that would be needed to destroy its chemical-weapons stocks.[1]

Even with this relatively vague level of available detail regarding North Korean WMD stockpiles and related infrastructure, the experiences of Kazakhstan can assist in envisioning what elimination operations may be required and the time and resources they might entail, and in setting parameters that would help guide the rapid-fire decisions that may be necessary in future contingencies. Though it is far from having exact knowledge or blueprints, the types of details we know now regarding the elaborate systems at Stepnogorsk could offer hints about the infrastructure and equipment that North Korea’s WMD programs may entail. By Alibek’s account, the roughly two dozen buildings at Kazakhstan’s primary Soviet-era bioweapons site included giant testing chambers, fermentors, ovens, and centrifuges; extensive general laboratory facilities; equipment for filling, transporting, and storing munitions that could someday deliver the biological materials; and, hidden below the buildings, an elaborate underground network of bunkers, pipes, and ventilation and waste systems.[2]

Kazakhstan’s cases show that the following questions would be important to address in considering possible future North Korea operations, no matter who might conduct them:

- What security conditions would be necessary for the international community to be comfortable securing and destroying North Korea’s WMD materials in place, compared to removing them for destruction in other locations?

- What physical conditions of the WMD materials and their surrounding environment could limit or prohibit various disposition options, including moving the materials or safely eliminating them on-site? For example, what additional options may be necessary or desirable for WMD materials and delivery systems that are in quantities or conditions that make them lesser proliferation risks?

- How might North Korea’s nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons experts be gainfully employed in eliminating the threat of the programs they helped to operate?

- What unexpected costs and other hurdles might arise from various projects to eliminate, convert, or secure in place dangerous materials and dual-use equipment?

- Would there be hurdles to the commercial viability of conversion projects, for example for chemical or biotech-related facilities?

- If the country’s WMD programs are someday to be verifiably eliminated in place, what weather conditions and environmental factors might hinder progress?

- What can help reassure the public that specific disposition options are safe?

This work could be carried out quietly—and possibly in a wholly non-governmental manner—if North Korea’s neighbors and other stakeholders are concerned about it being seen as overly provocative to the regime. However, international organizations and countries should carefully consider the potential deterrent effects or diplomatic benefits of signalling that these questions are under consideration by the international community.

For North Korea as well as Syria, Libya, and other countries, it is not too early to develop concepts for employing former WMD scientists and others with tacit WMD-relevant knowledge. Despite today’s significant uncertainty regarding all of these countries, we know that their increasing rate of emigration may now or in the future include those with WMD expertise, and that for Syria and Libya the extensive WMD elimination work already conducted will likely leave fewer future jobs in this field for its capable experts. Kazakhstan’s experiences show that long-term civilian employment of those with WMD capabilities can become a serious challenge.

Governments, private and academic enterprises, and charitable foundations that work to reduce WMD risks could create an international coalition to address this issue, with a strong focus on enduring, long-term solutions. Given the involvement of South Korea, Japan, and other relevant partners, the ISTC may be well positioned for an important role, especially regarding North Korean scientists.

This examination of Kazakhstan reveals opportunities for further study that could shed light on how some of the above-mentioned questions might be addressed. The Ulba Metallurgical Plant and Stepnogorsk offer interesting contrasts in the viability of projects to convert former WMD-relevant facilities to purely civilian enterprises. Both were located in the same area and involved similar environments and actors, though they had very different histories, purposes, and equipment. Evaluating the differences and similarities between these two sites—and conducting a deeper review of their challenges and successes on their paths toward commercial viability—would help inform potential future WMD threat reduction projects. Similarly, examining Kazakhstan’s successful highly enriched uranium removal work with NTI in contrast to its unsuccessful public-private partnerships for Stepnogorsk would be informative. Finally, a comparative study of the structure, authorities, and operations of the small, ad-hoc teams frequently created for counter-WMD in Kazakhstan would be extremely informative.