Former Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev, who is known for ending the Cold War, dissolving the Soviet Union, and changing the map of Europe, died Tuesday, August 30. He was 91.

We asked several Center experts for their thoughts on Gorbachev and his impacts – and how his life and actions are relevant to the challenges the world faces today.

GRAHAM ALLISON, Douglas Dillon Professor of Government (former Belfer Center Director)

“When Mikhail Gorbachev became leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, the Cold War was at its height. Ronald Reagan, president of the United States, had declared the Soviet Union to be an “evil empire.” Soviet air defenses had accidentally shot down a Korean airliner, KAL007, killing 269 passengers. The hands on the doomsday clock managed by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists had moved up to three minutes to midnight. On the Harvard campus, students were calling for a “nuclear freeze.” At the Kennedy School, Joe Nye, Al Carnesale, and I were co-chairing a project called Avoiding Nuclear War. Five years later, this confrontation between two superpowers that had been the centerpiece of standard life for four decades had been consigned to the history books.

If you ask yourself which single individual contributed most to the resolution without war of four decades of Cold War between the U.S.-led free world and the Soviet Union, it was Mikhail Gorbachev.”

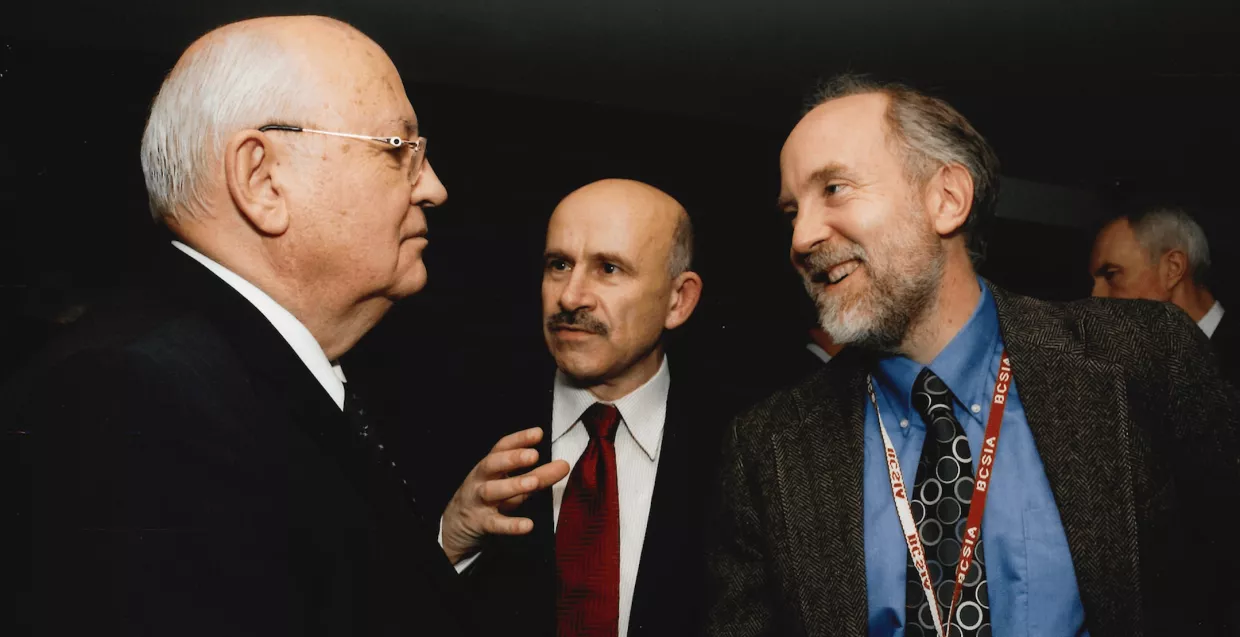

(This is an excerpt from Graham Allison’s introduction of Gorbachev at a Harvard Kennedy School JFK Jr. Forum in December 2007. See Allison’s complete introduction of Gorbachev at the end of this page.)

MARIANA BUDJERYN, Senior Research Associate, Project on Managing the Atom

“Mikhail Gorbachev dared to be honest with himself and with the people under Soviet rule about the hypocrisy and deep dysfunction of the Soviet system. He also had the courage to discard violence as the Kremlin’s principal tool of political control within its dominions. One of the consequences of his courage, unintended though it might have been, was freedom and prosperity for millions of Russians and Eastern Europeans, including the people of my own country, Ukraine. The incumbent Kremlin rulers are trying to reverse Gorbachev’s legacy of freedom with lies and violence. As Mikhail Sergeevich passes into history, it is our duty to remember and treasure his legacy, especially in this time of peril.”

MATTHEW BUNN, James R. Schlesinger Professor of the Practice of Energy, National Security, and Foreign Policy

“Every person on earth owes Mikhail Gorbachev a debt for dramatically reducing the chance that they would die in a nuclear holocaust. Through his contribution to ending the terrors of the Cold War and reaching the first arms control agreements that led to real reductions in nuclear arms and on-site inspections, Mikhail Gorbachev made the world a safer place for all of us.”

ASH CARTER, Belfer Center Director and former U.S. Secretary of Defense

“Mikhail Gorbachev’s passing inspired me to ask, ‘Suppose Gorby’s worldview, and not Putin’s worldview, had prevailed in Russia…how different would the world be?’ Some things would be unchanged: Russia would still be a nuclear power of the first magnitude because its Soviet-legacy nuclear stockpile is gargantuan even by today’s standards, and fissile materials have very long half-lives. Russia would be a middle-sized economic power whose greatest source of wealth is piped from the ground, not created in labs and businesses. The difference is that Gorbachev believed that Russia’s best future was one that was, broadly speaking, on a convergent path with the West’s. Not that Russia would even give up its distinctive non-western culture, or even give up Communism. But for Gorbachev and for Yeltsin after him, setting up Russia’s identity as one essentially defined by opposition to the West – which is Putin’s absolute number one principle of governance – could not lead Russia to the future it deserved. For all their failings, Russia’s first two post-Cold War leaders had a conservative vision for their country. It is much easier for national security leaders in America to build a bridge to leaders of Russia who don’t define their success in terms of setbacks for us.”

PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Senior Fellow, Future of Diplomacy Project

“While Gorbachev came up through the Communist Party hierarchy of the Soviet Union, upon coming to power, he recognized that the Communist system was not working. He genuinely believed that, through glasnost and perestroika, he could reform the dysfunctional and failing economy and eliminate the brutal repression of the Communist system. His policies, intended to advance "socialism with a human face," nevertheless, instead of salvaging the Communist system triggered democratic revolutions at home and in the near abroad. Significantly, when the Communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe started to collapse, he did not use force to save them. However, in Riga and Vilnius, he will be long remembered as having dispatched tanks to suppress the opposition. But Gorbachev will also be remembered as having ultimately supported a peaceful transition and end to the Soviet empire, including the historic reunification of Germany and the tearing down of the Berlin Wall.”

PAUL KOLBE, Director, Intelligence Project

“Mikhail Gorbachev, reviled in Russia and lionized in the West, neither engineered the collapse of the Soviet Union nor passively presided over its demise. Instead, he attempted to reform a system that was unreformable and in the process unleashed cascades of consequence that he neither foresaw nor could control. Economic rot, deep cynicism, and the yearning for freedom by peoples under the yoke of the Soviet empire all combined in a remarkable flood of change.

Gorbachev’s decisions to launch perestroika, to not use force to preserve the Berlin Wall, to back reunification of Germany, and to withdraw the Soviet Army from Eastern Europe set the stage for the USSR’s own collapse and his own vilification at home. In the decades that followed, Russians languished in bitter resentment at this loss of empire, but thanks to Gorbachev, millions in Eastern Europe, the Baltics, and the Balkans were able to seize the moment and build truly new societies free of Russia’s repression.”

JOSEPH S. NYE, Jr., Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor

“In 2011, when I attended Gorbachev’s 80th birthday celebration in Moscow, he was unpopular with the public for failing to preserve the empire. However, a spectacular group of Russian artists held a celebration for him and ended it by thanking him for giving them freedom. Then Putin took it away.”

Graham Allison’s Introduction of Mikhail Gorbachev at Harvard Kennedy School JFK Jr. Forum, “Overcoming Nuclear Danger,” December 4, 2007

“Fifty years from now when the Oxford University Press one-volume history of the 20th century is published, only two people on Earth today will be the subject of an entire chapter. One of them is our guest tonight, former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev.

As President Gorbachev and I were discussing at lunch today, many younger people are less familiar with the avalanche of recent history than they should be. So with his indulgence, let me recall:

When Mikhail Gorbachev became leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, the Cold War was at its height. Ronald Reagan, president of the United States, had declared the Soviet Union to be an “evil empire.” Soviet air defenses had accidentally shot down a Korean airliner, KAL007, killing 269 passengers. The hands on the doomsday clock managed by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists had moved up to three minutes to midnight. On the Harvard campus, students were calling for a “nuclear freeze.” At the Kennedy School, Joe Nye, Al Carnesale, and I were co-chairing a project called Avoiding Nuclear War.

Five years later, this confrontation between two superpowers that had been the centerpiece of standard life for four decades had been consigned to the history books. If you ask yourself which single individual contributed most to the resolution without war of four decades of Cold War between the U.S.-led free world and the Soviet Union, it was Mikhail Gorbachev.

Unlike some of his successors, Ronald Reagan had no hesitation about negotiating with leaders of countries he judged evil. As he confided to his diary, “Continued negotiation with the Soviet Union is essential. We need never be afraid to negotiate.”

President Gorbachev was acutely aware that the Soviet system he inherited was stagnating. He undertook to reform it with policies that he called “glasnost” which encouraged Soviet citizens to think for themselves and call things by their real names; and “perestroika” which meant a restructuring of the Soviet command and control economy. His goal was clear: to revitalize the Soviet Communist system.

What he accomplished was rather different. In the West, we honor Gorbachev for his decisive role in ending the Cold War—indeed in ending it with a whimper rather than the bang of a nuclear Armageddon that could have killed us all.

Eastern Europeans whose nations were members of the Warsaw Pact are grateful that Gorbachev reversed the previous policy of shooting people to prevent them escaping through barbed wire fences in Hungary or over the Berlin Wall—even when that meant the unraveling of that alliance.

Russian views are more complex. As a consequence of the forces Gorbachev unleashed, in December 1991, the Soviet Union disappeared. In its place there emerged a new Russia and 14 newly independent states including Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and the Baltics. A nation that had historically been imperialistically expansive was returned to its borders 300 years earlier under Peter the Great.

At the celebration of President Gorbachev’s 75th birthday in Moscow, a number of Russian citizens protested shouting abuses. Others reminded the protestors that Gorbachev was the individual who gave them the right to shout.

Russia’s current President, Vladimir Putin, has a much harsher view of this record. In his judgment, the collapse of the Soviet Union was “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.”

The strand of this story that brings President Gorbachev to Harvard tonight and tomorrow focuses on nuclear weapons. At the meeting between President Gorbachev and President Reagan in Reykjavik, Iceland in 1986, the two leaders talked seriously about eliminating all nuclear weapons—yes, I said all nuclear weapons. A year later in 1987, Gorbachev and Reagan signed the INF Treaty—zeroing out an entire class of intermediate nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. Tomorrow here at the Kennedy School a group of 45 policy-oriented scholars—15 Russians, 15 Americans, and 15 internationals—will spend the day with President Gorbachev exploring lessons from this successful INF Treaty for the nuclear challenges we face today from cutting Russian and American nuclear arsenals to nuclear terrorism.

The professor who taught me international politics here at Harvard, Henry Kissinger, once asked Chinese leader Zhou Enlai what he thought of the French Revolution. Zhou reflected and then said, “It’s too soon to tell.” About the revolutionary changes in which are guest tonight played such a decisive role, Zhou Enlai’s answer certainly applies. But there can be no doubt that he stood at the center of these storms.

It is thus a great honor and privilege to welcome back to Harvard tonight former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and to hear his reflections on the challenges we face today in overcoming nuclear danger.”

The entire Forum event can be viewed here.