I recently traveled to Worcester with my uncle to visit the grave of a family relative, Sarkis Manuelian, who died in 1985 at the age of 90.

Technically, he was not even my great uncle, but the cousin of my grandfather. He spoke with a heavy accent even though he came to this country at the age of 15, smoked bad-smelling cigars, and usually wore the same type of clothes — white or blue shirts, dark pants, and a straw hat. He was not famous or rich, but owned a corner spa (variety store) in Arlington in his later years after working in factories in Worcester and Chelsea in his early years. He had a heart of gold, however and was much loved by three generations of relatives. He was also an illegal immigrant, having sneaked across the Canadian–New Hampshire border when he was a teenager.

When I was a teenager I sat down with him one day to hear about his early life. He grew up in the village of Kesserig in the Kharpet province of the Armenian plateau in Anatolia, near the present-day city of Elazig in eastern Turkey. In 1910, at the age of 15, he decided to leave for America, either because he was looking for economic opportunity or because he sensed that bad winds were blowing. Five years later in 1915, the Ottoman government embarked on a methodical plan of genocide that killed more than a million Armenians and drove the rest into exile. All of Sarkis' immediate family — father, mother, brother and sister — were killed. Had Sarkis stayed in Kesserig, he would have almost certainly been one of the victims, as young men of his age were usually the first to be slaughtered.

Sarkis was very fortunate to have been in America at the time, but he suffered from the trauma of being here while his family was being killed over there. When he spoke to me many years later of his lost family members, his voice would begin to crack and he would pause for a long time, not knowing what to say. It was a pain that he carried with him for the rest of his life. Fortunately, some of his cousins (like my grandfather) survived and joined him in America, and they adopted him as a brother. The children of his cousins would respectfully call him Sarkis Keri, the latter word meaning uncle or more specifically, mother's brother, for he was related through my mother's side of the family.

As my brothers and I were growing up — not being fluent in the Armenian language — we would call him Uncle Keri, believing that the word "Keri" was his first name. My father, who did speak Armenian fluently, would chuckle at our poor use of the ancestral language, and Sarkis himself would get a good laugh as well. But he never corrected us, as he enjoyed the visits to the home of his cousin's grandchildren, and didn't want to appear as a disciplinarian.

Sarkis, who never married, was a fixture at family picnics and get-togethers. He was always generous and would slip us young kids money or candy. He even gave his old car to my brother. Later, I heard a story that in the 1940s he gave an Armenian-American student $300 (a lot of money in those days) so that he could complete his college education.

Why Sarkis slipped over the border from Canada in 1910 and not go through Ellis Island (as nearly all of my other relatives did) I never understood. Perhaps he caught a ship to Canada and didn't want, for economic reasons, to pay for another one to New York. Perhaps he heard about stringent health examinations at Ellis Island and didn't want to take a chance there. I don't know. But when he came to America — first to Worcester like so many immigrants — he worked long, hard hours in factories. In the 1930s, he took advantage of Franklin Roosevelt's "amnesty" for illegal immigrants and became an American citizen. He was very proud to be an American and cherished his citizenship after having been in "illegal" status for a couple of decades. Aside from his border-crossing episode, he was a law-abiding citizen except for a few games of pinochle with his cronies.

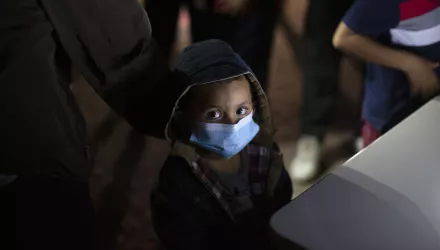

All of which brings me to the present immigration debate. Most of today's illegal immigrants did not face genocide in their homelands, but came here for economic opportunities. But like Sarkis, they are working long, hard hours, and contributing to the economic vitality of our country. Is it not better to legalize their status and have them become citizens down the road than to keep them in illegal status? The right-wing hysteria over "amnesty" for such people seems to me to be a bit un-American. After all, it was done in the past, and our country was better for it. And I think that many Americans, if they dig a little deep, have one or two Uncle Keri's in their family.

Gregory Aftandilian is a research fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and a former Middle East analyst at the State Department. Statements and views expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Kennedy School of Government or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Aftandilian, Gregory. “My Uncle 'Keri' and the Immigration Debate.” Lowell Sun, July 20, 2007