When working abroad for the CIA in the early 1990s, I received a senior officer from Washington on a mission to collect an important piece of evidence to help identify the culprits behind the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103. As we sat in a restaurant sipping a glass of wine, "Mike," a veteran counterterrorism agent, enumerated the reasons why the investigation was among the CIA's highest priorities. His eyes narrowed as he recalled that the terrorist attack on the commercial airliner had killed one of our own. "Terrorism is deeply personal business," he sighed. "It will be around as long as there are people with scores to settle." He continued, "Terrorists embarrass politicians, and their attacks are always painful for the families of their victims. But terrorism isn't a strategic problem. It won't affect our way of life, and it isn't a threat to our national security."

That might have been true at the time, but on 9/11, Al Qaeda rewrote the terrorist playbook by executing mass casualty attacks against strategic U.S. targets. In essence, these attacks ended one era and ushered in a new one. It is an age in which a few terrorists hold the means to alter the course of history with a single blow.

Having set a standard that dares to change the world, it is likely only a matter of time before 9/11 is eclipsed by an even more devastating event.

So why has it not happened yet?

For starters, having pulled off such a complex and successful operation as 9/11, Osama bin Laden may find it problematic to settle on anything lesser-or riskier-that might damage his movement's almost mythological standing in the annals of terrorist lore.

Al Qaeda is a conservative, risk-averse organization. The group's leadership apparently recognizes that it is better to not attack at all, than to do so in a way that falls short of the lofty goals they have set for themselves. And for now at least, the Al Qaeda leadership may have few credible options for making good on threats to disrupt the global economy and to convince their adversaries that they are fighting a war that cannot be won.

A further-and highly unsettling-explanation of Al Qaeda's extraordinary patience is that group members think time is on their side. They probably believe they have drawn the United States into a deepening commitment to fight a protracted insurgency in Afghanistan. Moreover, Saddam Hussein was deposed, opening up long-term possibilities for an Islamic theocracy in Iraq. Gen. Pervez Musharraf is out of power in Pakistan, and the domestic instability there is growing every day. These developments create opportunities to change the global status quo. In other words, Al Qaeda may be waiting for a perfect storm in the alignment of targets, opportunity, and timing to launch another game-changing attack.

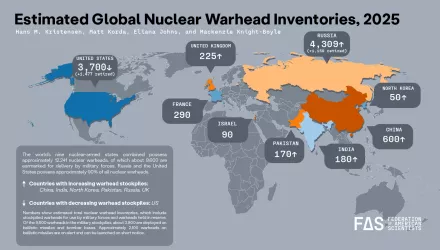

If they do so, it will certainly be based on a calculation that the moment is ripe to try to force Washington's hand in ways that favor Al Qaeda's long-term goals. In this light, the group's long-held intent and persistent efforts to acquire nuclear and biological weapons represent a unique means of potentially fulfilling its wildest hopes and aspirations. As bin Laden declared in 1998, it is his duty to obtain WMD. He apparently understood at this early juncture that using such weapons might become necessary at some stage of his confrontation with the United States and its allies. With this in mind, Al Qaeda feverishly pursued nuclear and biological weapons capabilities before 9/11. These efforts were managed by the group's most senior leadership, with a sense of purpose and urgency that suggests it was important to make progress on possessing WMD prior to its 2001 attack on the United States. Yet in spite of bin Laden's declaration and Al Qaeda's subsequent efforts to acquire nuclear and biological weapons, the threat is not widely being treated as a clear-and-present danger that requires an urgent response.

Nuclear terrorism detractors point out that the threat has been hyped. Unfortunately, it is true that some have used the WMD threat to incite fear and to justify extreme tactics to combat terrorism. Skeptics argue that there were no WMD in Iraq, so why should people believe intelligence that terrorists are seriously trying to acquire them? Plus, if terrorists have such a weapon, why haven't they used it? They also argue that it is impossible for men in caves to acquire and detonate a nuclear bomb. They acknowledge some nuclear material may be missing from global stocks, but they exude confidence that it is surely not available in sufficient enough quantities to constitute a real threat, and that in any case, it is preposterous to believe that primitive, unsophisticated terrorists might be able to construct a bomb capable of producing a nuclear yield. Let us hope the skeptics are right, because in terms of organizing the international community to confront the threat posed by large-scale WMD terrorism, not much has been accomplished.

Intelligence and law enforcement agencies, in the United States and abroad, have been slow to dedicate resources and leadership to the problem. For example, there is a widespread assumption that terrorists will employ small-scale, crude forms of chemical, biological, and radiological weapons because they are easier to acquire and use. But the weight of the evidence suggests the opposite is true-i.e., terrorists choose weapons best suited for the targets they intend to strike.

The history of Al Qaeda strikes against the United States bears this out. The group historically has utilized a remarkably diverse arsenal of weapons in its attacks against the United States: The embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania were ground attacks; the U.S.S. Cole bombing was a sea attack; and the World Trade Center and Pentagon bombings were air attacks. It chose the desired weapons based on operational considerations, most notably a weapon's capacity to destroy the intended target. Another dangerous bias in assessing the threat is the belief that once terrorists obtain a nuclear bomb, they will use it. Thus, the following argument is proffered: Since Al Qaeda has yet to use a nuclear weapon, it does not possess one. This might comfort the doubters, but terrorists may not agree that it is difficult to stash a nuclear or biological weapon in a safe place for future use, without fear of discovery. After all, it has proved exceedingly difficult to find bin Laden and his lieutenant Ayman al-Zawahiri, and we have a pretty good idea of where they might be hiding. Plus, nothing in Al Qaeda's behavior suggests that its leaders follow predictable patterns concerning the means and timing of attacks.

But accepting that nuclear terrorism can happen does not mean that it is inevitable. The odds are stacked against a terrorist successfully acquiring a nuclear bomb. That said, in a twenty-firstcentury world of rare and unpredictable events, prudent risk management must prioritize threats based on both the probability of an event and its potential consequences. Accordingly, terrorists must be denied any possibility, however remote it might seem, from ever succeeding in their quest to launch a nuclear or largescale biological attack on any city. Better still, if we can anticipate how a nuclear terrorist threat might unfold, it stands to reason that we might be able to prevent such an attack from happening.

The following scenarios are the nuclear nightmares that keep me up at night.

To continue reading the paper, download the PDF below, available in both English and Russian:

Mowatt-Larssen, Rolf. "Proliferation and Terrorism: Big Hype or Biggest Threat?" Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 66, no. 2 (March/April 2010).

The full text of this publication is available via Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.