You fight the pandemic with the tools you have. Being deeply involved with the leaders across the computing space, focused on the future of computing, I was able to work with these stakeholders across Government and the private sector to rapidly stand-up the COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium. This represents the largest collection of processing power ever dedicated to a single topic: fighting COVID-19. My experiences in this effort, detailed below, highlight to me the benefits of an ongoing dialogue between sectors and between competitors, enabled by neutral actors such as the Government, and the subject of my first Policy Brief. Specifically, I content that these blended research communities can act as a strategic reserve for solving the Nation’s problems in times of crisis – but only if they are nurtured and cultivated for the pursuit of a public purpose in their overall effort.

Five days in March

By March of 2020, the United States had pivoted to an all of Government approach for fighting COVID. Sitting at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), leading the U.S. coordination efforts in quantum information science and future computing, I wanted to help. One of the first things I learned once I started volunteering my interest, expertise, and strategic situation, was that everyone wanted to help. Often, a specific vision for outcomes that would matter was murky or missing. Sometimes the best thing to do was to let others do their assigned role, rather than mucking up the works. However, in one case, it was clear that we needed to take action.

Dario Gil, a member of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), called up my boss, and asked whether high performance computing (HPC) systems – the supercomputers that can attack uniquely challenging science problems – could be better brought to bear in the fight, volunteering IBM’s systems to help. That night, I was asked explore what a partnership between the private sector and government could do to leverage HPC for the fight. Wednesday came to an end with a flurry of emails, phone calls, and creation of a short vision for execution. The goal: launch by Monday.

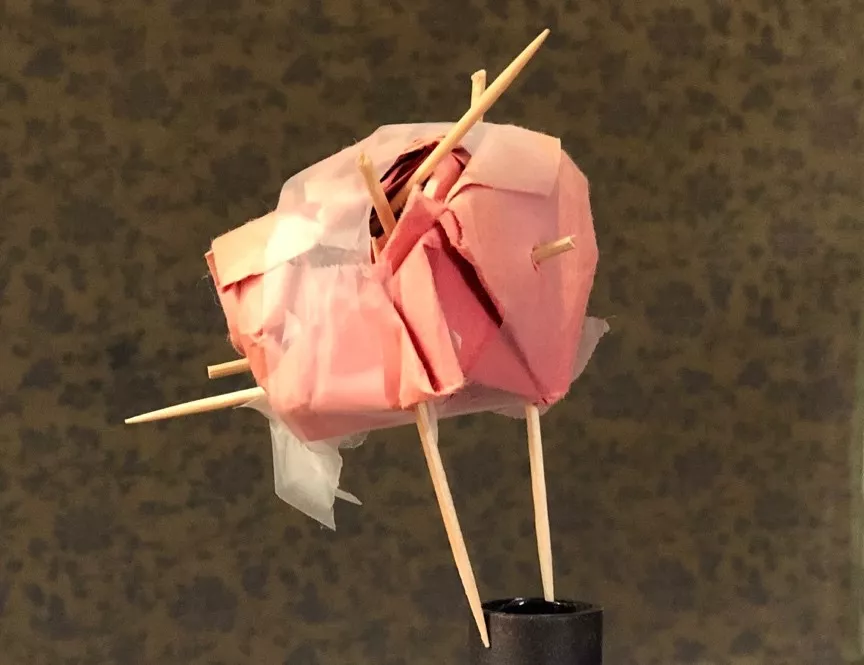

A SARS-CoV-2 sculpture given to me by my eight-year-old son, in recognition of all the time his dad was spending on fighting COVID. Photo Credit: J. Taylor

Fortunately, I have had the opportunity to build other public-private research and development efforts. This type of institution building takes time. For example, under the National Quantum Initiative, we built the Quantum Economic Development Consortium (QED-C) over the course of three years. It started with a dialogue with industry members though a quantum industry day hosted at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. It built through interactions with potential not-for-profit partners to host a consortium and through the inclusion in the National Quantum Initiative Act of 2018 of a requirement to explore starting such a consortium. Meetings with stakeholders and development of informal agreements to enable formal agreements all came together over that three-year period for the eventual launch of a 160 member-strong entity.

I knew for COVID we would have to move faster. But when everyone’s interests and effort align, and when there is trust between the Government and the private sector engendered through many repeated interactions and joint work, such rapid progress becomes possible. Specifically, OSTP had already been deeply engaged with the future of computing community through our efforts to update and expand the National Strategic Computing Initiative, launched in 2015. There had been substantial concern in the research and supercomputing communities that the Trump administration would drop this, as it was an executive order signed by President Obama. However, instead we adopted and improved the key elements, ensuring that the future of computing community would be able to make rapid and strong progress over the coming decade (for an outside perspective: https://www.hpcwire.com/2019/12/02/nsci-update-adapting-to-a-changing-landscape/). In a practical sense, this meant that OSTP and our future computing team had developed trust and understanding with the major private sector and public sector efforts in the field.

Setting Up for Success

Over Thursday, we worked through that trust to negotiate with key agency leaders at the Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, and NASA to ensure a path for use of U.S. Government resources through this partnership. At the same time, we expanded the discussion to crucial private sector entities throughout the supercomputing space to gain agreement for the use of, and access to, their private systems and cloud-based resources. Working from within the future of computing community, we had the right tools on hand – trusted relationships, a network of people ready for execution, and understanding of the approach for success – to bring it together.

It was critical to ensure that the mission of this new consortium was clear, and that the process reflected the mission. We focused on enabling rapid scientific investigations in support of the fight against COVID. Thus, the process for use of supercomputing resources was focused on the most important science. At the same time, by having a clear mission, we could ensure that the value proposition for all the partners remained clear and focused.

We also needed appropriate governance, both at a high level and at an operational level. The NSF suggested use of their gold-standard peer review community through the existing xcede.org proposal system. All of the partners agreed to provide technical expertise to rapidly assess proposals, and the leadership team quickly agreed to keeping proposals short (three pages) and focused (six months or less to impact). An ad-hoc steering group, later formalized, provided top-level economic, political, and scientific insight and support.

Finally, we kept the legal agreements as lightweight as possible. This allowed us to start in days, rather than years. In many respects, our approach leveraged knowledge gained in implementing platform economy systems. In both those systems and in the HPC Consortium, efficient selection and matching is the key task, while implementation of the research relies upon the direct agreement between the supercomputing provider and the researcher, through their existing mechanisms. By acting as a ‘fast-track’ path to an existing process at each partner, the consortium itself plays the role of highlighting key options for partners, rather than directing specific usage.

Launch and Lessons

Launch came that Sunday night, when the President announced the formation of the COVID-19 HPC Consortium and the real work began. Over the coming months, I was asked in other areas of the government how we had built this 40+ party partnership with big tech companies, universities, agencies, and even foreign entities, on such short notice. Looking back, it was clear that I followed the same steps I had followed for the QED-C, but on a much shorter time-table. The essential ingredients were consistently the same: trust and community.

Fortunately, I’ve now had time to reflect on what we can learn from these experiences. I encourage those interested in the principles behind lightweight partnerships of this nature to take a look a my first Belfer policy brief, available here: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/public-purpose-consortium-enabling-emerging-technology-public-mission

Fundamentally, the strategic reserve provided by a public-purpose consortium is a dramatic benefit in times of need. Furthermore, due to our availability heuristic, we often underestimate the probability of high-impact events such as war, famine, drought, and pandemics. It is not that these events are unforeseeable, but rather they become unimaginable. And yet, knowing that great challenges are likely to come, it is crucial to lay in the stock necessary in our scientific and technical ecosystem to ensure America is ready for the next crisis before it arises. Only then do we have the tools in hand when the time comes.

In the coming months, I will be exploring this theme in greater detail. For today, however, I would like to encourage researchers around the U.S. to reflect on how their community can maintain a trusted network for times of need, and what stands in the way of being ready when a critical moment comes. How can we do this better, more consistently, and what missing elements of authorities or laws are in the way? What steps should we take to ensure that America always has a strategic technological reserve?

Taylor, Jake. “Research Communities: A Strategic Reserve in Times of Crisis.” October 21, 2020