Throughout both my research and my personal experience in government, there’s one pattern I’ve seen emerge time and again when it comes to technology. Government outsources a lot of the technical skills that, in other tech-forward organizations, would be in-house. Positions for core technical leaders like Product Managers and Tech Leads, key roles for designing and developing mission-critical systems, and even the central braintrust for custom-built software are all filled by contractors and vendors – in other words, they’re outsourced.

Government doesn’t often think about contracting as outsourcing, but that’s effectively what it is. Some could argue that the government has a much tighter relationship with vendors than what might come to mind when you hear the word “outsourcing,” but I don’t think that’s necessarily true. Plenty of software contractors are siloed away, tossed requirements over the wall only to toss a “finished” product back over. And even in the cases where contractors and government employees do build tight bonds and relationships, this only strengthens the hold that this particular vendor has – if they were to be replaced, that relationship would dissolve, taking all those benefits and investments with it.

We need to bring more technical knowledge and skills in-house. The benefits are clear: You’re able to build and retain knowledge in the long-term. You don’t have to worry about contract structures or limitations when the need to react quickly arises. You know that the incentives for the individual are aligned much more closely to your organization. And, perhaps most importantly, the experience of actually working on the project becomes an investment in your own internal technical capacity, rather than building the capacity of the vendor.

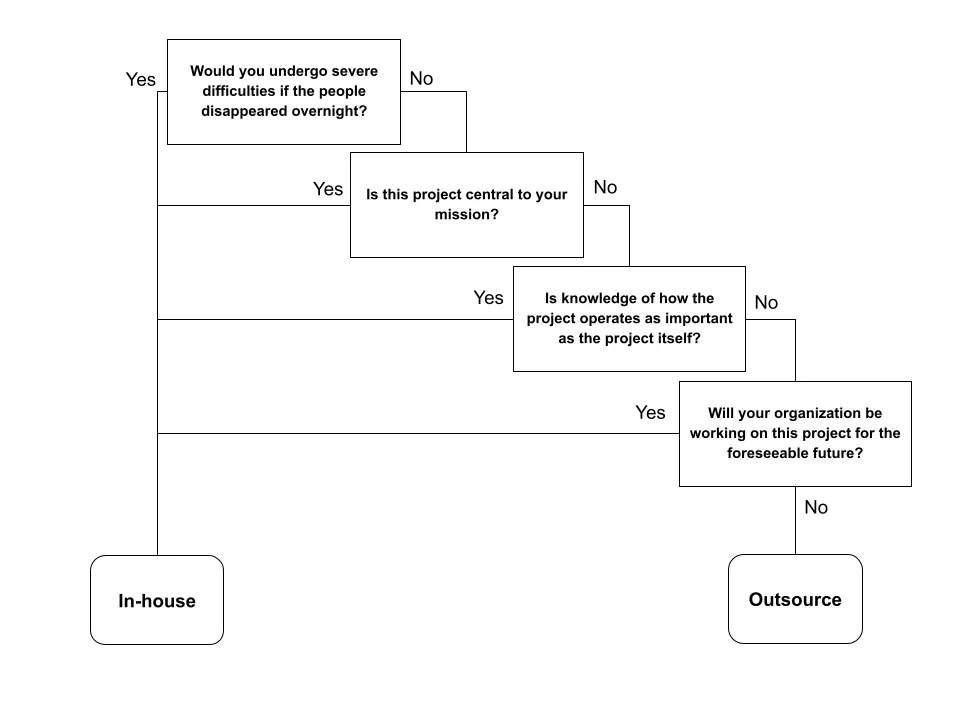

To help make the case for bringing more technical talent in-house, I’ve assembled a set of guiding questions to help government executives figure out whether a particular role or set of roles should be in-house vs outsourced. There will certainly be cases where using vendors will be preferable, but I believe it’s time we invest more in bringing people into the fold directly, rather than relying so heavily on vendors.

Would you undergo severe difficulties if the people involved in this project all disappeared overnight?

This is my favorite litmus test for determining whether this particular need should be fulfilled by in-house or outsourced resources. I’ve worked on many projects where contract end-dates had to be extended over and over because of a risk that the contract would lapse before a new one could be awarded (oftentimes to the same vendor). The need for the continued presence of these vendors was so great that the government couldn’t go more than a few days without having them working on the project.

If this is the case for your work as well, I heavily suggest that this role shouldn’t be filled by people who could disappear overnight. If the company goes under, or something unexpected happens, your lines of support could be gone very rapidly. If this is the type of service that can be replaced easily with a competitor, then there are no real worries – if one call center contract falls through, you can likely find another one fairly rapidly. But if it would take that competitor weeks or even months to ramp up the needed knowledge to be effective, then you’re looking at a situation where in-housed workers would be more beneficial.

Is this project central to your mission, or an ancillary aspect of it?

If you’re working with vendors to fill a need that is absolutely central to your organization’s mission, then you’re giving a vast amount of power to the vendor. Sometimes this can work well – there are plenty of vendors that have built specializations that might align with your particular mission, as is often the case in the Defense sector. But in many other situations, this locks your organization into a one-way dependency on that vendor. If you absolutely cannot function without this role or service, then you likely want to ensure it’s filled by permanent staff within your own organization.

Is knowledge of how the project operates as important as the project itself?

This gets to the “braintrust” issue I mentioned earlier. In my previous role at the U.S. Digital Service (a good example of what it’s like to bring technical talent in-house), I worked on a large, complex, and mission-critical software system within the Department of Homeland Security. All of the technical knowledge of the system – the software architecture, the database schema, the problem areas and features and the overall shape of the software – was held by four Tech Leads, all of whom were contractors. Losing these particular individuals (let alone the vendors as a whole) would have put the project back by months if not years. These tech leads were the greatest individual resources on the project, and yet they could be lost at any moment due to the fungible nature of contract fulfillment.

Will your organization be working on this project for the foreseeable future?

If this project is something that your organization will be doing for years or decades to come, then it’s a good idea to build that expertise within your own organization. It makes sense to bring outside help for short-term efforts. But if a long-term strategy for your technical organization is, say, to manage a deployment platform for all services, then you’ll want key knowledge of that within your own teams.

If you’ve answered “Yes” to any of the above prompts, then I highly encourage you to invest in this specific role as an in-house resource. You’ll have more stability, expertise, availability, and sustainability by having key talent resources as a part of your own team, and any investments you make on those people will translate directly onto the projects your organization will work on.

To be clear, I’m not advocating for all outsourced vendors to be replaced by in-house talent. There are significant benefits to working with outside vendors, and a strong public-private relationship is key to leveraging modern tools and practices. But an overreliance on outsourced support for core positions, such as Tech Leads or Product Managers, leaves the government without a core understanding of the services that it builds and provides.

Bringing these talents and skills and people into your own organization will likely be difficult – you’ll have to use new hiring authorities, modernize your hiring pipeline to move more quickly, build new position descriptions, recruit in non-traditional spaces, and attain more billets at the right levels. But that challenge is well worth the reward of the resilience and internal capability you’ll be building up as a part of it.

Got any thoughts on this essay? Disagree with some of my points, or have thoughts on how to expand this list? I’d love to hear from you! Give me a shoutout on Twitter at @_mjlerner, or shoot me an email at mlerner@hks.harvard.edu.

Lerner, Mark. “Should this role be in-house, or outsourced? .” February 26, 2021