Our weekly COVID-19 and Economic Diplomacy tracker looks at policies that impact the coordination of international governments and central banks, ongoing commentary and analysis, and asks what these turbulent times mean for economic diplomacy.

We’d love to hear what you think. Send us your comments, and be sure to follow us on Twitter @BelferEDI.

The Highlights

- Multilateral policy coordination has been in short supply, say market observers, especially compared to globally coordinated efforts that nations undertook in response to the Great Financial Crisis.

- Cases continue to rise in the United States, as the federal government debates its next round of fiscal stimulus. Market observers credit the Federal Reserve for shoring up market conditions worldwide, despite its reluctance to be “the world’s central bank.”

- As the European Union inches closer to agreeing on the terms of its 750 billion euro recovery fund, debate turns to how to raise E.U.-wide revenue to fund debt service.

- The International Monetary Fund revised down its growth forecast for the year, saying the global economy would shrink by 4.9% as a result of the virus and ensuing lockdowns. Analysts continue to debate how emerging markets will navigate debt forgiveness and the global scramble for medical supplies.

Global Policy Coordination

Economic diplomacy fundamentally asks how nations coordinate (or not) in formulating their economic policies. Analysts are increasingly criticizing the lack of international coordination in the global response to COVID-19, particularly relative to the coordination during the Great Financial Crisis. During the last crisis, for example, G-20 meetings, convened by U.S. President George Bush and continued by President Obama, coordinated significant stimulus spending and backed expanded funding for the IMF and World Bank. This time around, no such productive multilateralism is to be found. In its place, analysts note the trade barriers erected to hoard medical supplies and the United States’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization, and question what will become of multilateralism.

- Stewart Patrick, writing in Foreign Affairs, recalls American diplomat Richard Holbrooke’s quip that criticizing the United Nations for failures of multilateralism was like “blaming Madison Square Garden when the Knicks lose.” Multilateralism is what national leaders make of it. The crisis has revealed the failings of the international system, and the failings of the WHO and the economic response of developed nations in particular, Patrick argues, but that should encourage leaders to invest in a more effective multilateral system that incentivizes states to cooperate rather than compete. “One lesson that will emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic,” Patrick writes, “is that multilateral cooperation can seem awfully abstract, until you actually need it.”

- In the Economist, editor Daniel Franklin writes in a special report on the 75th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations that “global leadership is missing in action.” He faults the vacuum left by American leadership — the WHO withdrawal, the insistence on calling COVID-19 the “Wuhan Virus” that derailed a G-7 meeting — but also China’s bungled initial response, and Europe’s closed borders. The future of global multilateralism may not yet be settled, but global cooperation through multilateral institutions is uniquely suited to addressing global problems such as global pandemics and climate change. That view is surprisingly popular: 61% of people in 32 countries surveyed by Pew had a favorable view of the U.N., and a recent survey of Americans showed 70% thought America should play an active role in world affairs. The COVID-19 crisis may be just the excuse the world needs to reform multilateralism.

- Looking at the broader economic system in which multilateralism exists, Martin Wolf, in the Financial Times, comments on the new book by Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis, Trade Wars are Class Wars. The book’s authors argue that recent underconsumption and the “global savings glut” are a result of income having shifted to the wealthy, who have a higher propensity to save. The U.S. trade deficit and “debt bubble” results from the global demand for U.S. safe assets, driven in large part by high savings rates in China and Germany (and recently the E.U. in general). That has policy implications, Wolf argues: “If foreigners want to hold American liquid assets in vast amounts, the U.S. must run a huge external deficit.” The questions are whether policymakers can shift income to those who are willing to spend it, and whether the world economy can resolve the challenges of “running a globally integrated economy with a national money,” the U.S. dollar. Until we answer these questions, Wolf says, we should expect trade wars to continue.

U.S. Developments

No major developments in U.S. policy this week, as the country awaits updates on whether and how the federal government will extend stimulus efforts, namely the increase to unemployment benefits that is set to end at the end of July. Cases of COVID-19 are rising, notably in Texas, raising concern about the ongoing reopening. Meanwhile, analysts are reflecting on the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve’s actions earlier in the crisis to calm international markets, but also on the Fed’s reluctance to be “the world’s central bank.”

- Vice President Mike Pence writes in an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that, no, there is not a second wave. “Cases have stabilized over the past two weeks,” Pence says, “with the daily average case rate across the U.S. dropping to 20,000—down from 30,000 in April and 25,000 in May.” He cites expanded testing and production of medical supplies and equipment, and progress towards developing therapeutics and a vaccine as positive factors. These developments, Pence concludes, are “a cause for celebration, not the media’s fear mongering.”

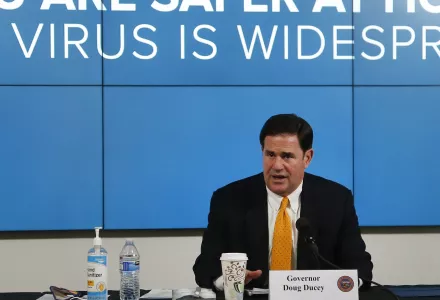

- Dr. Anthony Fauci testified before Congress on Tuesday, expressing concern at the “disturbing surge” of COVID-19 cases. States such as New York, he said, are doing well; but he cited Florida, Texas and Arizona as areas of concern. Fauci added that it is still too soon to tell whether deaths from COVID-19, which have been falling in the last week, will continue to fall or pick back up.

- Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, speaking at a Bloomberg event, indicated the Trump administration was considering another stimulus package as early as July. Details could be released in the next few weeks. Mnuchin added that this stimulus “will be much more targeted and much more focused on jobs and bringing back jobs.” But he reiterated that the administration is reluctant to enter another shutdown phase if COVID-19 cases continue to increase.

- “The federal reserve steadfastly refuses to view itself as the world’s central bank,” writes the Economist this week, “which is a pity, because it is becoming quite good at the job.” As market confidence cratered early in the crisis, investors pulled money out of markets that funded $10 trillion of liabilities at non-U.S. banks. Securing dollar funding became suddenly costly. Japanese life insurers, who need dollar funding to buy dollar-denominated assets, were particularly vulnerable. Eventually, the Federal Reserve’s swap lines, extended to more central banks and on looser terms, made it easier for foreign financial institutions to meet their dollar funding needs. Stress in the system abated, and a sense of normalcy returned: borrowing through swap lines has decreased as of June 11th. Nonetheless, notes the Economist, the Fed is “uncomfortable making quasi-diplomatic decisions about swap lines. It knows that by picking some countries, it risks sowing doubt about others.”

- The Economist article references a longer study (“US dollar funding markets during the COVID-19 crisis – the international dimension”) by Egemen Eren, Andreas Schrimpf and Vladyslav Sushko at the Bank of International Settlement (BIS), published in May.

- In the New York Fed’s Liberty Street Economics blog, Nicola Cetorelli, Linda S. Goldberg, and Fabiola Ravazzolo review how the Federal Reserve’s dollar swap lines for foreign central banks supported the domestic U.S. corporate credit market. Swap lines, as we detailed in an earlier post, provide standing dollar funding to foreign central banks, which can lend it to their banking sector. Foreign banks’ offices in the U.S. account for 10% of the U.S. banking system, including $700 billion of loans mainly to U.S. corporations. In March, as the economic shock of COVID-19 became clear, corporations drew down their credit lines from banks. Offices of foreign banks in the U.S. were able to meet these withdrawals by drawing on dollars from their parent banks, which obtained funding through their central bank’s swap line with the Federal Reserve. While much commentary on swap lines focuses on the stabilization of international dollar funding markets, Cetorelli, Goldberg and Ravazzolo show how the Fed’s policy flows through the global financial system to support credit back in the United States.

European Developments

Negotiations continue over the European Union’s recovery fund, which under the current proposal would provide 750 billion euros, mostly in grants, to struggling countries financed by a form of joint E.U. borrowing. E.U. leaders are meeting today to formally discuss the proposal. More immediately, there are growing signs that the German government and the European Central Bank will resolve a standoff with the German Constitutional Court, which called into question the German central bank’s participation in ECB asset purchases.

- Europe is taking a page from U.S. financial history in its proposed recovery fund, says the Peterson Institute of International Economics’ Jacob Funk Kirkegaard. How will the E.U. pay back the new funds it raises, Kirkegaard asks? Revenue generated by the E.U. itself — “traditional own resources,” or TOR — would help to ease the burden on member states, but unlike in the U.S., which can tax citizens directly, the E.U. is more limited. The E.U. proposal, however, bears resemblance to U.S. federal revenue prior to personal income tax in 1913, which drew on import tariffs, “sin taxes” (alcohol, tobacco), and corporate tax. In addition to import tariffs paid to the E.U., the new proposal would raise revenue through corporate taxes (10 billion euros on multinationals and 1.3 billion euros from a digital tax) and through expanding its carbon emissions trading scheme (call it a “21st century climate ‘sin tax’”).

- Polish development minister Jadwiga Emilewicz, however, pushes back on the emissions trading scheme, calling the proposal “absolutely unacceptable” in an interview with the Financial Times. Poland currently generates 80% of its electricity from coal. But that is as a result of decisions in Moscow, Emilewicz says, which excluded Poland from the development of nuclear power plants during the Cold War. “That history matters in this moment,” Emilewicz says.

- Martin Arnold reports at the Financial Times that Berlin and the ECB may be closing in on a solution to the German Constitutional Court ruling against the ECB’s bond buying program. The court required that the German government provide proof of the ECB’s “proportionality” assessment, to show that the program did not come at the undue expense of other policies. The ECB plans to provide the German government with documentation on its monetary policy meeting, including the full non-public minutes, where it evaluated proportionality. “I am confident that we will find a way to make the considerations of proportionality clearer,” said Jens Weidmann, president of the Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank.

- In an interview with Der Spiegel, Luis de Guindos, Vice President of the ECB, responded to questions about the constitutional court issue (and many more tough questions some German observers have been asking the ECB). “We have taken note of the judgment from Karlsruhe. Our monetary policy decisions have always been proportionate and appropriate,” says de Guindos, adding that “We stand ready to cooperate with the Bundesbank and to provide information to facilitate the response that the German institutions have to give to the Constitutional Court.”

- Olaf Scholz, the German Finance Minister, said he expects Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio to increase from 60% to 77% as a result of fiscal stimulus related to COVID-19. Sholz called the new borrowing, which at 219 billion euros dwarfs the 44 billion euros it borrowed during the financial crisis, “a lot of money” but also “manageable.” Notably, with interest rates on German government bonds near historic lows, Germany’s interest payments will amount to less than they did before the financial crisis, despite total borrowing being higher.

Emerging Markets

The IMF revised down its forecast for global growth: it now says global GDP will decrease by 4.9% this year, more than the 3% decrease it predicted in April. But the IMF also highlighted the easing in financial conditions, citing $11 trillion in fiscal stimulus worldwide combined with accommodative central bank policies. Still, observers remain concerned about the ability of developing nations to fight the virus while meeting debt payments, and whether private creditors will join debt relief plans.

- David Malpass, president of the World Bank, says he expects private creditors will join the G-20 debt relief program extended to over 70 of the world’s poorest nations. The program would see debtor nations secure relief from part of an estimated $140 billion in debt-service obligations this year, funds that could be redirected to fight the virus. A full 60% of money owed by creditor nations, however, is due to China, says the World Bank. Malpass says he is “encouraged” by China’s debt relief efforts so far: Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged last week to waive the debt of and extend maturities for some African nations, although details have yet to emerge.

- Harvard Kennedy School professor Ricardo Hausmann, in an editorial in the Financial Times, warns that those who oppose IMF lending “may have blood on their hands.” Although the IMF has, by historical standards, responded “quickly and massively,” Hausmann writes, that response now appears to be “both slow and modest.” Though the IMF has $1 trillion to lend, constraints on lending tied to a country’s quota render the IMF “a big fire engine with an obstructed hose.” Hausmann argues the IMF must lend more, as it did to European countries during the 2011 sovereign debt crisis. Even arguments that have merits against increasing lending capacity — whether through increasing quotas, disbursement limits, or Special Drawing Rights — may not stack up against the suffering developing countries are sure to face.

- Anne O. Krueger, former World Bank chief economist and former first deputy managing director of the IMF, argues that for emerging markets, funding is good but medical supplies are better. With global constraints on the supply of medical goods (and eventually vaccines) funding for medical purchases will lead to increased prices. Instead, “countries that need medical supplies and equipment should receive goods in kind” argues Krueger. That calls for an allocation mechanism, which Kreuger says should be led by the WHO.

Odds and Ends

- Argentina’s debt restructuring talks may be collapsing.

- Anne Case and Angus Deaton: “Between rising "deaths of despair" among working-class whites and higher COVID-19 mortality rates among African-Americans, the stunning secular decline in US life expectancy will continue.”

- COVID-19 is revealing how many norms economists take for granted, writes Kaushik Basu, which has implications for policies we implement in response.

- Welcome the wokeness of the Federal Reserve. “Monetary policy should look at the margins, not just the aggregate economy,” writes the FT’s Martin Sanbu.

- “Long live Jay Powell, the new monarch of the bond market”

Cassetta, John Michael. “The Week in COVID-19 and Economic Diplomacy: ‘Going It Alone?'.” June 26, 2020