A Memoir of the 9/11 Commission

The 9/11 Commission was "set up to fail." So says its chairman, former Republican Governor of New Jersey Thomas Kean. "If you want something to fail," he explains, "you take a controversial topic and appoint five people from each party. You make sure they are appointed by the most partisan people from each party--the leaders of the party. And, just to be sure, let's ask the commission to finish the report during the most partisan period of time--the presidential election season." He could have added that President Bush and Republican leaders in Congress had agreed to create the commission only under unrelenting pressure from the families of the victims, and also that Congress had given it a meager budget and a requirement to get all its work done in a scant eighteen months. He could have added, too, that he was the president's second choice as chairman, Henry Kissinger having stepped down after sixteen days because of the demand by the families that he disclose the names of clients of his consulting firm, and that Kean started under the handicap of never having worked in Washington. It was to be mid-March 2003 before he even had the security clearances needed to read pre-September 11 intelligence reports.

As late as December 2003, with the deadline for the commission's final report only five months away, pundits were debating whether it would even get its Warholian fifteen minutes of fame. But things worked out very differently. The commission's hearings provided headline news from January to June. When it issued its final report in July (having wrested a two-month extension from a resistant Bush and an even more resistant Dennis Hastert), the front page bore the signatures of all ten commissioners. Not one, Republican or Democrat, dissented from a single word in the report's 567 pages. Newsday typified media commentary when it called this election-year bipartisanship "miraculous." Equally surprising was the fact that Congress stayed in session to debate the commission's recommendations and that, in December, many of those recommendations became law.

Preceding the report's two chapters of recommendations are eleven chapters on the history of September 11. The New Republic described these chapters as "novelistically intense." Time said they held "one of the most riveting, disturbing and revealing accounts of crime, espionage and the inner workings of government ever written." And John Updike commented in The New Yorker that the King James Bible was "our language's lone masterpiece produced by committee, at least until this year's 9/11 Commission Report." It was even nominated for the National Book Award.Clearly something extraordinary had taken place.

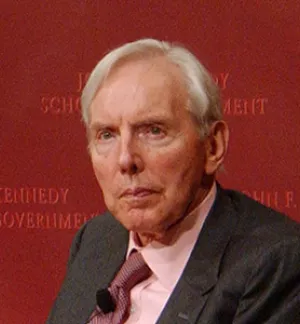

The overall success of the commission was the result of many factors. Insistent, emotional, but hardheaded lobbying by the families was critical. So was the calm, undeviatingly bipartisan leadership of Kean and his vice chair, Lee Hamilton; the dedication of the other eight commissioners; and the skillful management by the commission's "front office"--executive director Philip Zelikow; his deputy, Christopher Kojm; and general counsel Daniel Marcus. As the commission's senior adviser, I was a fourth member of this "front office," but I had no managerial responsibility. My job was to help produce the historical narrative.

For this task, I had two comparative advantages. The first was a long career as a historian. The second was a lack of partisan bias. Many years earlier, I had been a commissioner myself. The commission was to recommend laws making presidential papers public property. (From Washington's time to Nixon's, they had been private property.) The statute required that one commissioner be a Republican, one a Democrat, and one nonpartisan. I was the last, and was so certified by a 100-0 vote in the Senate. For commissioners and staff who suspected that some part of the 9/11 report might get a political or ideological slant, my OK seemed to be something like a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.What follows is my own brief and blinkered account of how that narrative came into being.

To read the full article, please click here.

May, Ernest. “When Government Writes History.” The New Republic, May 23, 2005