Trick, Not Treat at COP16: UN Biodiversity Conference Sees Slow Progress on 30x30 Target

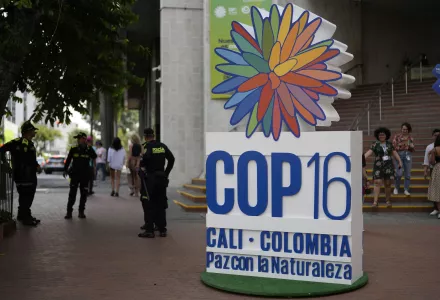

Roy Family Fellow Bhuvan Ravindran MPP 2026 shares his key takeaways from COP16 in Cali, Colombia.

Roy Family Fellow Bhuvan Ravindran MPP 2026 shares his key takeaways from COP16 in Cali, Colombia.

On Halloween, an eleven-year-old child dressed as a sea turtle stood outside the venue for the Working Group on resource mobilization at the UN Biodiversity Conference in Cali, Colombia. He asked Party negotiators to “treat and not trick” this time, by giving candy (funds) to the turtle (biodiversity).

The 16th Conference of Parties (COP16) to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was the first COP after the landmark Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was agreed upon in 2022. The GBF consists of four long-term (2050) goals and 23 short-term (2030) targets on preserving and restoring biodiversity. The failure of its predecessor, the decadal Aichi Biodiversity Targets (2011-20), created an expectation of greater ambition, resource mobilization, and accountability. But compared to the swell of hope for planetary recovery present at COP15, the underwhelming commitments made during COP16 suggest slackening momentum and forgotten lessons.

I was in Cali at COP16 last month to observe multilateral negotiations on the CBD, understand interests and roles of different stakeholders globally, and get up to speed on policy, technology, and financial innovations in biodiversity conservation. But since there’s also COP29 happening in Baku right now, I should clarify that this is the year of the ‘Rio Trio’: the three United Nations sister Conventions on climate change, biological diversity, and desertification drawn up in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. From October to December, each of them is hosting a Conference of Parties (COP) that are signatories to their respective Conventions. In contrast to the climate COP, the biodiversity COP meets biennially as opposed to annually and attracts little clout. To illustrate, while COP28 in Dubai last year was attended by over 150 heads of state and 85,000 people, COP16 in Cali this year saw 6 heads of state and nearly 23,000 attendees.

The Earth’s ecological integrity.

I thought I was walking into an ‘Implementation COP’. Countries were required to submit updated National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) that aligned with the ambitious GBF targets, and developed countries would support those plans with adequate funding support. However, only 44 out of 196 nations submitted updated NBSAPs, and the required funding was not pledged. Developed countries (with Quebec as the first sub-national contributor) offered up USD 396 million—far short of the USD 20 billion that developed nations are required to mobilize by 2025 (Target 19).

Scientific research suggests that 30-70% of the planet must be preserved to sustain and restore biodiversity. To that end, countries were expected to act on the 30x30 target of the GBF, which requires conserving and restoring 30% of the Earth by 2030 (Targets 2 & 3), particularly ecologically significant terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Since the 30x30 goal is the bare minimum, its effectiveness depends on two things. First, the quality of conservation i.e., the areas conserved must be well-connected, ecologically representative, and equitably governed. Second, the remaining 70% of the Earth must be sustainably managed. So we need to achieve 30x30, and gradually scale up our efforts from there. To support the GBF targets, Parties agreed to globally mobilize USD 200 billion annually by 2030 (Target 19) and eliminate USD 500 billion in harmful subsidies by 2030 (Target 18).

While a multilateral mechanism for benefit sharing from digital sequence information (DSI) was operationalized and the ‘Cali Fund’ for DSI announced, there was insufficient action to preserve the Earth’s sensitive web of life. Discussions will continue in the intersessionals.

As negotiations got underway on the penultimate day, ominous rain clouds covered the sky. As I stared at the beautiful "Biodiversity Jenga" in COP16’s blue zone, I wondered if we were shying away from asking the right questions by constructing and pursuing the wrong imperatives.

Say we already had the billions that we need to preserve 30% of the Earth’s biodiversity: would the current extractive models of economic growth be ready to transition away? Could developed economies moving towards carbon neutrality avoid extraction of transition minerals in biodiversity-rich developing nations? If the Earth’s integrity is premised on interdependence, can siloed policy design and processes conserve nature? Do we need finance, regulation, or intent?

While multilateral negotiations have become more interdisciplinary in their approach to solving the climate and biodiversity crisis, answers to these questions require transdisciplinary thinking that transcends precedence. For example, economists may be required to think beyond the confines of market-based frameworks, to conceptualize economies that value assets and costs to nature and define what is economically feasible in that counterfactual. Policymakers may have to mimic the interdependence of Earth’s ecosystems in governance structures, through greater coherence and inter-ministerial cooperation that transcend departmental priorities for collective interests. The role of academia and civil society will be key in facilitating and mainstreaming this reimagining.

Though negotiations focused on legal jargons and national constraints, new ideas and initiatives were freely exchanged in the side events. Examples of leadership in policy coherence, transboundary cooperation, supply chain traceability, Indigenous resilience, and innovative finance inspired hope for a breakthrough.

On innovative finance and transboundary cooperation, five African nations are working on what could be the world’s first multi-nation debt-for-nature swap to preserve a shared coral ecosystem while raising USD 2 billion. On policy coherence, Colombia, the host country, announced how its national biodiversity targets have been aligned with positive climate outcomes, and nearly 22 climate targets in its Nationally Determined Contributions are linked to biodiversity. Towards its UNFCCC COP30 Presidency next year, Brazil signaled creation of biodiversity and climate strategies that are closely interlinked. The negotiated text at COP16 also acknowledged the ocean-climate-biodiversity nexus and suggested the possibility of a joint work Program of the three Rio Sister Conventions. The innovative leadership being demonstrated by biodiversity-rich economies in transition speaks to the strong relationship with nature inherent in these cultures.

With over 82% of current biodiversity financing coming from public sources, Target 19 of the GBF recognizes the role of the private sector and financial instruments like biodiversity credits to bridge the gap. This COP had a noticeably large private sector presence, reflecting a rising recognition of the sector’s impacts and dependencies on biodiversity, and the negative economic cost of inaction. The role of the private sector and trade was discussed widely in transitioning to a nature-positive world i.e., economic growth based on not just impact reduction, but ecosystem enhancement. It’s a double leapfrog from the current nature-negative trajectories we are on, and skips over the ‘net-zero’ milestone to a net-addition approach. Private nature-negative financial flows equal $5 trillion i.e., 140 times more than private investments in nature-based solutions. This was the first COP with a dedicated trade day, recognizing that nearly $3.4 trillion worth of global exports come from biodiversity-based products.

There was an acknowledgment by leading manufacturers on the importance of integrating financial risks of negative ecosystem impacts into corporate decision making for ensuring long-term stability of supply chains as well. Enhancing traceability of supply chains through stricter regulation and innovation (e.g., block chain) to enhance transparency in sustainability reporting was also discussed. No clear solution emerged for balancing extraction and conservation in biodiversity- and mineral-rich nations around the Amazon in South America and the Congo Basin in Africa. Indigenous communities and some civil society representatives were concerned that interest was more skewed towards including the private sector as opposed to excluding fossil fuels, even as global subsidies for fossil fuels exceeded $1 trillion for the first time ever in 2022.

Protected and conserved areas currently stand at 17.6% of terrestrial land, and 8.4% of marine, inland, and coastal waters. Therefore, there is a lot of work left towards reaching 30x30. With conversations moving towards coherent global governance of the climate and biodiversity agendas, the climate COP30 in Brazil, as opposed to the biodiversity COP17 in Armenia, could likely emerge as the next checkpoint for progress on biodiversity goals.

A lot rests on national and sub-national actions, and non-state actors will play a key role in bolstering the effort. Our little human sea turtle will be there yet again, looking the negotiators right in the eye. What will it be, trick or treat?

Ravindran, Bhuvan . “Trick, Not Treat at COP16: UN Biodiversity Conference Sees Slow Progress on 30x30 Target.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, November 15, 2024