A man watches a TV screen showing file footage of U.S. President Donald Trump, left, and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un during a news program at the Seoul Railway Station in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, April 9, 2018.

As preparations are being made for a potential meeting between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, it is tempting to analogize to other bold disruptive actions that have upended years of stagnation in policy, such as when President Ronald Reagan and Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev met in Reykjavik and imagined getting rid of all nuclear weapons, or when President Richard Nixon opened relations and traveled to the People's Republic of China.

While prior policies toward North Korea’s relentless efforts to build nuclear weapons and their delivery systems have not proven successful, there is great risk in an encounter between the American president and the North Korean leader. President Trump needs to be fully cognizant of past North Korean perfidy and steer clear of any rushed agreements with negative future consequences.

There are several good reasons to get talks underway, even if it is unusual to start at the top of the power pyramid with a meeting between two leaders of such divergent stature.

First, the international sanctions regime has grown stronger across multiple American administrations and it has rightly been strengthened over the past year in response to the threat presented by Pyongyang’s advancing nuclear and missile programs. Most important, China recognized the real risks of continuing to enable the regime, and has cut back on its economic relationship, particularly in providing vital crude oil, putting a significant squeeze on Kim’s already strapped economy.

Second, Trump’s fiery rhetoric has led to the growing fear of nuclear war in the region and beyond. The taunting threats — with an American president using words such as “fire and fury” — appear to have been sufficiently unsettling to create momentum for engagement between the Republic of Korea and the North, and now to the possibility of a direct U.S.-DPRK leaders’ meeting. Unfortunately, this kind of brinksmanship could escalate into nuclear war, but it should now be exploited to reap any potential beneficial outcome and to avoid the worst.

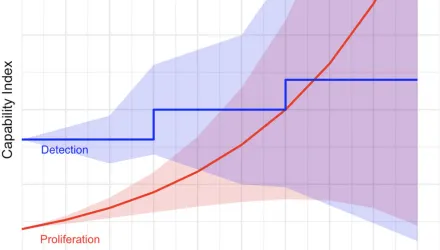

Third, the steady march of Kim’s nuclear and missile development programs means that time is not on our side. The better the arsenal he builds, the harder it is to take it apart. The United States and its allies have vital interests in constraining the growth in size and capability of Kim’s weapons as soon as we can and then dismantling the entire program. I know from personal experience how hard it was to dismantle legacy Cold War nuclear arsenals, and this case will present unique new challenges, but the place to begin is by changing the context of the overall relationship.

However, there are four reasons to be extremely cautious, and for which President Trump and his team need to be thoroughly prepared:

First, the North Koreans have a long and well-documented track record of cheating on prior nuclear agreements. It’s important to recall that there are two paths to building nuclear weapons: via plutonium reprocessing and via uranium enrichment. The most notorious violation by Pyongyang was that while abiding by restraints on plutonium reprocessing negotiated during the Clinton administration they aggressively pursued a covert uranium enrichment pathway to the bomb. For any agreement to freeze now or potentially reduce over time, there must be stringent monitoring and verification measures in place with international inspectors permitted in multiple locations inside North Korean territory.

Second, those who seek to limit U.S. leadership in Asia are poised to exploit this process to drive wedges between us and our ROK and Japanese allies and, more perniciously, seek to reduce our military presence in the region. The fact that Kim made a surprise visit to Beijing last week points to the reality that China is playing chess, not checkers. American strategic interests extend far beyond the challenges presented by Kim Jong Un, and thus the outcome of these talks must not include any agreement to diminish U.S. security cooperation with Asian allies and partners, or reduce the U.S. footprint in the region. For starters, the Trump team needs to be clear that the significant U.S. troop presence on the Korean peninsula is not a negotiating chip.

Third, the early retirement of many of the most experienced U.S. diplomats and the absence of an American ambassador in Seoul to guide this process may be a positive sign to those who see the State Department as a sinecure for pin-striped old thinkers. The reality is that the women and men who work in Foggy Bottom and at posts abroad have expertise that is essential to ensuring that any conversation and potential negotiation takes account of the history of this difficult challenge and the wide range of U.S. interests that are at stake in resolving it. To assume that experience is an obstacle to progress in this instance puts us at a disadvantage.

Finally, President Trump’s expressions of determination to abrogate the Iran Nuclear Agreement create an illogical context for embarking on this perilous path. Either the North Koreans anticipate that they can have no confidence in American commitments reached during a negotiation, or they assume that they can breach an agreement early because the United States will have no staying power anyway. Both outcomes would disadvantage American security and the security of our allies in Asia and across the world.

Ironically, Trump’s willingness to meet with Kim creates a stronger case for continuing to implement an agreement that is evidently working while embarking upon the high-risk meeting between a sitting American President and the hitherto isolated leader of North Korea.

Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, a Senior Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, is a former Deputy Secretary of Energy and White House Coordinator for Defense Policy, Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction and Arms Control in the Obama administration.

Sherwood-Randall, Elizabeth. “A Bold and Risky Gambit: The Trump Play on North Korea.” The Hill, April 13, 2018