Abstract

In explaining the development of institutional structures within states, social science analysis has focused on autochthonous factors and paid less attention to the way in which external factors, especially purposive agent-directed as opposed to more general environmental factors, can influence domestic authority structures. For international relations scholarship, this lacunae is particularly troubling or perhaps, just weird. If the international system is anarchical, then political leaders can pursue any policy option. In some cases, the most attractive option would be conventional state to state interactions, diplomacy, or war. In other instances, however, changing the domestic authority structures of other states might be more appealing. In some cases, domestic authority structures have been influenced through bargaining, and in others through power. Power may reflect either explicit agent-oriented decisions or social processes that reflect the practices, values, and norms of more powerful entities.

In 1978, Peter Gourevitch published an article called the “The second image reversed: The international sources of domestic politics” (1). The reference was to Kenneth Waltz's division of international relations theories into first, second, and third images, where the first image referred to individual or psychological explanations for war and foreign policy, the second image referred to the impact of domestic factors, and the third image referred to systemic conditions (2). Gourevitch (1) argued that causality did not flow in one direction. The second image could be reversed; external factors could influence institutions and politics within states [Waltz (3) himself recognized that the international environment could impact on the character of states through selection and imitation].

During the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, the insight of Gourevitch (1) languished. The third image, international interactions, dominated international relations scholarship during the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, whether in realist or neoliberal institutionalist guises. International relations scholars focused on the bipolar relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union or after 1990, the problems of market failure that could be resolved by international institutions that were created by agreements among states.

Although comparativists were more attentive to the ways in which external factors could influence domestic structures, they emphasized general environmental conditions rather than specific initiatives taken by leaders in other states. The three main ways of understanding political development—modernization theory, institutional capacity, and rational choice institutionalism—all took account of the international or transnational environment. For modernization theory, transnational technological change was the uncaused cause that accounted for social mobilization and industrialization, developments that led to the creation of a large middle class with values that were conducive to democratic development. For institutional capacity, the famous aphorism by Tilly (4) war makes the state and the state makes war, pointed to the way in which foreign threat prompted the creation of stronger state institutions. For some versions of rational choice institutionalism, external threat was one important driver of the state's need for more capital, a need that led to self-enforcing institutions that made it possible for the state to make credible commitments to creditors (5).

However, neither international relations scholars nor comparativists paid systematic attention to the possibility that external actors might consciously attempt to alter the domestic institutional structures of other states. Hobbes's legacy, reflected in Weber's definition of the state, has weighed heavily. Our intellectual traditions have blinded us to the fact that states might not be autonomous; their domestic authority structures might be determined not just by autochthonous factors and international environmental pressures but also by conscious decisions made by policy makers in other states or more obliquely, social processes that reflect the values, norms, preferences, and interests of the more powerful.

For international relations scholarship, this lacunae is particularly troubling or perhaps, just weird. If the international system is anarchical, then political leaders can pursue any policy option (6). In some cases, the most attractive option would be conventional state to state interactions, diplomacy, or war. In other instances, however, changing the domestic authority structures of other states might be more appealing. Although much of the focus of scholarship during the Cold War was on relations between the Soviet Union and the United States, many of the initiatives that these two states pursued, including all of the overt interventions by both countries, were designed to alter the domestic authority structures of other states. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Afghanistan, Korea, and Vietnam, as well as many covert actions, were about promoting communism or capitalism in target countries and changing their domestic authority structures. For realism, there is a logical contradiction between the ontological assumptions of autonomous states and anarchy. If there is anarchy, then some states may not be autonomous (i.e., their authority structures may be influenced or controlled by other states). The Soviet satellites during the Cold War are one obvious example.

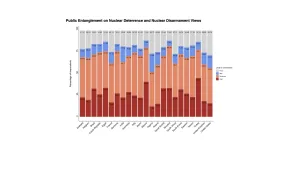

In the last decade, a body of literature has developed that is more attentive to the ways in which external factors, especially conscious decisions by leaders in other states, can influence domestic authority structures. At least in part, this attention reflects contemporary political challenges. Relations among the world's major powers, their state to state interactions, are more benign than they have ever been. Why this is so has been contested—growing democratization, nuclear weapons, changing international norms, especially in the North Atlantic community—but it is uncontestable that it is this way. The major threats to international peace and security now come from badly or malignly governed states or transnational actors with limited resources rather than from those states with the most formidable capacity. Foreign policy now often aims not so much at balancing against another power (although the American military is certainly doing this balancing with regard to China) or cutting deals that can move parties to the Pareto frontier but rather, at trying to the alter domestic authority structures in target states.

This work makes it clear that states cannot be treated as hard shells whose domestic structures are unaffected by external factors. The external environment does not operate just through incentives, economic or military, that prompt political leaders to alter policies or authority structures. External factors may also operate through bargaining or power. In the case of bargaining, national actors might seize on opportunities in the external environment that allow them to restructure their own domestic political institutions, including giving up autonomy or control over some policy domains: political leaders use their international legal sovereignty, their right to enter into contracts, to compromise their Westphalian/Vattelian sovereignty, the autonomy of their domestic institutions. Power involves situations in which the autonomy of a polity is violated through either the conscious policies of external actors or the social processes that weaker states cannot resist. State development, the character of institutional structures within states, is not an autochthonous process.

Modalities of Contracting and Power

In an article published in 2005, Barnett and Duvall (7) suggest that power can be distinguished along two dimensions. The first dimension is relational specificity, which can be either direct or diffuse. The second dimension contrasts “interactions of specific actors” and “social relations of constitution” (ref. 7, p. 48). The discussion yields a 2 × 2 table (Table 1).

Compulsory power involves the direct control of one actor over the existence or behavior of another actor. Institutional power is exercised through institutions that reflect the preferences of more powerful actors. These two categories track to the familiar actor-oriented logic of most political science analyses. Structural power involves constitutive relations in which one more powerful actor constitutes the identity, preferences, and capabilities of the other actor. Master and slave is the classic example. Productive relations involve the constitution of identities and capacities through diffuse social discourse (ref. 7, pp. 48–57). This taxonomy is not meant to be mutually exclusive: different kinds of power may be involved in any particular transaction.

Power, even as expansively conceived in the taxonomy of Barnett and Duvall (7), is not the only way in which institutions can be changed from the outside in. External actors can also influence domestic policies and structures through processes of collective choice in which agreement is reached through voluntary agreements or contracting. Hence, a conceptual mapping of the way in which the external environment has influenced domestic authority structures and domestic politics can begin with five categories.

- i) Voluntary contracting that alters domestic policies or authority structures.

- ii) Compulsory power, which can involve either direct coercion or coercive bargaining (the ability of an actor with go it alone power to alter the opportunity set facing weaker players) (8).

- iii) Institutional power in which more powerful states set the rules of the game by which other actors must play.

- iv) Constitutive power in which more powerful actors establish the basic character—the capabilities and identities—of units that operate in the international system.

- v) Productive power in which discourse alters the identities and capabilities of actors.

Bargaining and Contracting.

Liberal institutionalist arguments about collective choice dominate contemporary analyses of international politics. States enter into agreements that allow them to move toward the Pareto frontier. In some cases, these agreements create institutions that overcome market failure problems. Most of these deals involve specific policies. States, for instance, join military alliances or trade agreements in which they promise to follow policies contingent on other signatories doing the same. Some agreements, however, involve not just policies but also domestic authority structure. Although benefits might be far from equal, no state can be worse off as a result of such voluntary arrangements; otherwise, it would not enter into the agreement in the first place.

Contracting that has altered state authority structures has taken a variety of forms. These modalities, arranged from the least to the most intrusive, have included:

- Joining international organizations to reinforce particular domestic authority structures.

- Contracting with other states for the provision of core state functions such as security.

- Creating supranational institutions that have supremacy over national authority structures.

Reinforcing domestic institutions.

Voluntary agreements involving external actors or international organizations can be used to reinforce domestic institutional arrangements. Moravcsik (9) has pointed out that Germany was the most enthusiastic supporter of the European Convention on Human Rights, which was drafted in 1950. This fact, Moravcsik (9) argues, was not because human rights were deeply embedded in the German polity but just the opposite. The leaders of the new Federal Republic strongly backed the European human rights regime, because they wanted to lock in the new structures that had been put in place in Germany, structures that were partly the result of the Allied occupation. The level of domestic support for these new institutions was uncertain (9).

Simmons and Danner (10) have argued that the International Criminal Court (ICC) can serve as a commitment mechanism that can help to resolve civil conflicts in countries with weak domestic accountability mechanisms. Joining the ICC involves a loss of sovereign prerogatives. The Rome Statute creating the Court denies sovereign protection to heads of state. The ICC Prosecutor can initiate action against individuals in a member state without the permission of that state. The state cannot pick and choose over which issues the Court might have jurisdiction. The kinds of countries that have been most likely to join the court, Simmons and Danner find (10), are principled, highly accountable peaceful states and violent states that have weak domestic accountability structures. For the former, there is no cost to joining the ICC. Their citizens will never be prosecuted: the Court must operate according to the principle of complementarity; it must defer to national courts if those courts are functioning effectively. For the latter, the ICC can serve as a commitment mechanism for a political leader that wants to end civil strife. Joining is a signal that the government intends to constrain the level of violence, because if it fails to do so, its leaders would be subject to prosecution by the Court. By raising the ex post cost of defection, political leaders can send a costly signal to their own followers and their adversaries that they do intend to terminate hostilities. Simmons and Danner (10) find that accountable governments that have experienced civil wars are much less likely to join the Court. Their own domestic institutions provide them with the opportunity to make credible commitments without sacrificing the sovereign prerogatives that membership in the ICC entails. Thus, counterintuitively, governments in violent states with weak institutions join the ICC to lessen the likelihood that domestic institutions will crumble completely (10).

Pevehouse (11) has found that democratic consolidation more generally can be facilitated by membership in international organizations. Political leaders in newly democratizing states have credibility problems. They may not be able to convince their constituents that they are committed to democratic institutions: new institutions may be weak, and populist or other temptations to defect may be all too apparent. Membership in international organizations can ameliorate commitment problems by raising the cost of defection. International organizations create lock in by providing information, increasing the cost of violating property rights, credibly threatening sanctions against military coups, and creating a reputational cost for withdrawal. Mansfield and Pevehouse (12) find that democratizing states are more likely to join international organizations, especially those states whose members are democratic, than other states (11, 12).

Some preferential trade agreements provide for international arbitration of disputes or have been designed to create or strengthen particular institutional structures in partner countries, not simply to reduce trade barriers. The trade and investment treaties signed between the United States and Europe on the one hand and developing countries on the other hand have usually included provisions for institutional reform. Developing countries sign not just because they want access to American or European markets but also because the agreements serve as a commitment mechanism. Changes in domestic laws or regulations alone may not be very convincing for potential foreign investors, because such actions can be reversed. Changes instituted as a result of preferential trade agreements are more likely to be enduring, because if the signatory country reneges, it would also lose export markets (13).

Contracting with other states or official international entities for the provision of core state functions.

In Hierarchy in International Relations, Lake (14) argues that hierarchical bargaining and contracting is a common feature of the international system, a phenomenon that has been largely ignored because of the hold that legal concepts of sovereignty have had on international relations scholars (ref. 14, pp. 45–51). Lake (14) points to a number of examples in which states have delegated, through contracting, core state functions. The dominant state provides public goods for the subordinate state. The subordinate state, in turn, makes commitments with regard to not only policies, such as bandwagoning with rather than balancing against the dominant power, but also authority structures. The most dramatic examples are cases where states have entirely contracted out the provision of international security. In the 19th century, these entities would have been termed protectorates. In the contemporary environment, states that rely on others for the provision of their external security enjoy full international legal sovereignty and recognition. Examples include The Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, which have formally contracted with the United States for the provision of security (ref. 14, chapter 3).

When contracts are with other official entities, states, or permanent or ad hoc international organizations, such treaties may involve full delegation or partial delegation. Full delegation involves arrangements in which the external actor exercises state functions such as policing and is exempt from domestic law. In partial delegation, external actors are directed by both their home and host countries; they are not exempt from national law (15).

The Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands offers an example of voluntary contracting of core government functions with full delegation. In 2003, the Solomon Islands government was on the verge of collapse. Gangs had seized weapons from armories in the capital and even robbed the treasury. The political leaders in the Solomon Islands saw that they were about to lose power. They asked Australia and other Pacific countries for assistance. Acting under a Chapter VI United Nations resolution, legislation passed by the Solomon Islands, and the endorsement of the Pacific Islands Forum, a consortium of states led by Australia, took control of key financial activities, including the auditor general's office and parts of the police and judicial systems. Australia sent 2,000 troops to the Solomon Islands to restore order. The Participating Police Force can act without approval from the Islands’ authorities. Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands personnel are exempt from civil and criminal law while performing their duties. The cost for Australia has been substantial, about $200 million/y (15, 16). The leaders of the Solomon Islands would have preferred the status quo ante in which they were able to govern (or exploit) without ceding authority to external actors. However, after the government's de facto control crumbled, sharing sovereignty was the next best outcome.

Supranational institutions.

The European Union (EU) is the most dramatic example in the contemporary international environment of the use of voluntary contracting to alter domestic authority structures. The member states of the EU have used their international legal sovereignty, their right to enter into treaties, to compromise their Westphalian/Vattelian sovereignty by creating supranational institutions and subjecting themselves to qualified majority voting. The rulings of the European Court of Justice have supremacy and direct effect in the courts of the member states. For those countries in the Euro zone, the European Central Bank sets monetary policy. The members of the EU take many decisions by qualified majority voting, a practice inconsistent with the conventional notion of sovereignty. Candidate states must accept literally tens of thousands of acquis before they become members, not that these acquis are all necessarily honored.

In sum, state structures can be strengthened or created from the outside in through voluntary agreements in which states alter their own domestic authority structures through agreements with external actors. In some cases, these agreements have had a consequential impact, such as using external providers for the delivery of public services. In other cases they have even more deeply intruded into domestic authority structures, with the EU being the most dramatic example.

Power.

Domestic authority structures have been changed not just through voluntary agreements but also through power. Following Barnett and Duvall (7), power can take several different forms: compulsory, institutional, structural, and productive.

Compulsory power.

The clearest instances of power involve the use of military force and occupation, which is one example of what Barnett and Duvall (7) call compulsory power. Compulsory power has been used, with some frequency, to not just defeat other states in war, sometimes seizing some of their territory, but also to change domestic authority structures. The transformation of Germany and Japan after the Second World War were not isolated cases. Between 1555 and 2000, Owen (17) has identified 198 cases of what he calls “forcible domestic institutional promotion.” States that do intervene with others do so repeatedly. They promote institutions that are similar to their own institutions in other countries. The targets of intervention, Owen (17) argues, have been strategically important but unstable states. Interventions have occurred most frequently when the international environment has been characterized by high insecurity and deep transnational ideological divisions. Owen (17) identifies the Reformation and Counter-Reformation from 1550 to 1648, the French Revolution and the conservative reaction from 1789 to 1849, and the 20th century from 1917 to 1991 as the three periods during which the rate of intervention was highest.

For the United States, Lake (14) has identified 22 instances of militarized disputes between 1900 and 2009 in which the objective was to change the regime or government of the target state. Peceny (18), using a different dataset, identifies 33 interventions for the period 1898–1996 where the United States explicitly promoted democratization. A majority of these interventions occurred in the Caribbean littoral. Before the Second World War, the most important motivation for American interventions was anxiety about European involvement in bankrupt states close to the American border. After the Second World War, the most important motivation for American action was the fear that a state would leave the informal American empire and ally with the Soviet Union (14, 18). In most instances, the push for democratization came from the president, especially, Peceny (18) argues, if the international environment was relatively benign, American leverage was high, and conditions in the target state were promising. If the president did not initially identify democratization as a target, he might succumb to pressure from Congress to maintain a supportive domestic coalition (ref. 18, p. 4). Consistent with the finding of Owen (17), ideology can motivate the specific goals of intervention, especially the desire to make the domestic authority structures in target states look more like the structures of the intervener.

Foreign imposed regime changes can be consequential, although not always in the way that the intervener intended. Efforts to create stable democratic regimes through foreign intervention have been challenging.

Interveners do not always have an incentive to create such regimes regardless of their rhetoric, because they have less leverage over a truly democratically elected leadership (19). External actors may have limited ability to create the array of nonstate structures—free press and civil society organizations—that underpin full-fledged liberal democracies. Empirically, the number of cases in which democratization has been associated with external coercive intervention is small. For military interventions occurring between 1946 and 1996, one study identified five cases of United Nations intervention associated with democratization and three cases of United States intervention associated with democratization (20).

There is evidence that foreign imposed regime change can reduce the likelihood of a recurrence of international conflict. Changing militaristic leaders, breaking up industrial cartels, rewriting educational curricula, supporting domestic leaders with desirable preferences, insisting on constitutional change, limiting the size of the military, and in some cases, imposing democratic institutions can alter both the institutions and preferences of political leaders in target states (21). The individuals and institutions that supported belligerent activity can be eliminated. At the same time, foreign-imposed regime change seems to make civil wars more likely. The common underlying cause may be that war and the imposition of a new regime weaken the state's infrastructural power or domestic sovereignty and its ability to extract resources and regulate domestic activity, making it more difficult to confront foreign opponents but at the same time, more likely that domestic dissidents can challenge the regime (22).

Efforts to alter regime characteristic through compulsory power can involve coercive bargaining and not just the use of force. Coercive bargaining occurs when a state or group of states has go it alone power, the ability to take the status quo off the table to leave other actors with a newly constrained opportunity set. These other actors would have preferred the status quo ante, but it is no longer available. They may then enter into a voluntary agreement. This agreement leaves them worse off than they were initially but better off than they would be without an agreement. In conventional bargaining, even when the payoffs are asymmetrical, all actors move to the Pareto frontier, although some may move more than others. With coercive bargaining, some actors are worse off than they were in the status quo ante. The ability to take the status quo off the table and thereby, constrain the possibilities that are open to other actors can be understood as a form of compulsory power (8).

The relationship of the government of Liberia with foreign donors after the end of the civil war in 2003 offers an example of go it alone power involving external control of domestic authority structures. In 2005, the government of Liberia signed a contract with the International Contact Group of Liberia, whose members included the European Union (EU), the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the United Nations, the United States, and the World Bank, to create the Governance and Economic Management Assistance Program (GEMAP). GEMAP gave outside experts cosigning authority in key government ministries and state-owned enterprises, provided for the creation of an Anti-Corruption Commission, gave customs collection to an external contractor, and placed an international administrator as head of the Central Bank. A World Bank and United Nations study concluded that “GEMAP stands out in terms of the scope and intrusiveness of multilateral international engagement in public finance management in a sovereign country. It targets the collection of revenues and the management of expenditure but also addresses government procurement and concessions practices, judicial processes, transparency and accountability of key government institutions and state-owned enterprises, and local capacity-building” (ref.23, p. 17).

GEMAP was created as a result of initiatives taken by external donors who feared that government corruption was so extensive and deep that it would destroy the peace-building process that had begun in 2003. Government officials in Liberia would have preferred the status quo, which allowed them ample opportunity to pilfer. Foreign donors—the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, EC, and the United States—however, took the status quo off the table. They threatened to withdraw aid if Liberian officials refused to sign the agreement and impose a travel ban on the head of the government, threats that were credible because the donors were better off not giving aid at all than giving aid, much of which was being stolen (ref. 23, pp. 11–13 and 20).

Institutional power.

Domestic authority structures can also be influenced by institutional power, situations where power is exercised by agents but through institutions rather than directly. These institutions reflect the preferences of those agents with greater capacity. The institutions, however, are not epiphenomenal. More powerful states cannot change rules at will. The transactions costs for renegotiating rules can be high. Institutions are, in the first instance, the result of compromise among relevant parties.

The transition from the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to the World Trade Organization (WTO) offers an example of institutional power. The problem confronting developing countries with regard to the renegotiation of the international trade regime in the 1990s is an exemplary case of Gruber's (8) go it alone power, here exercised through institutions. Under GATT, developing countries could pick and choose among obligations. With the WTO, they were offered an all or nothing deal. All countries joining the WTO had to accept not only the GATT, which was related to trade in goods, but also about 60 other WTO agreements. There was no opportunity for opting out of specific agreements. The most important WTO agreements aside from the GATT are the Agreement on Agriculture, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), the Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary Measures Agreement, and the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade. If there had been an opt out provision, development countries would have rejected some of these agreements. The GATS and the agreement related to intellectual property rights were particularly problematic. Few developing countries have service sectors that can compete internationally. Joining the GATS makes any equivalent of infant industry protection more challenging. This problem might, of course, be beneficial for the consumers of services but would not be welcomed by nascent service industries and their political allies. In intellectual property rights, the interests of industrialized and developing states are at odds. Developing countries would prefer weaker intellectual property rights; the generators of intellectual property stronger rights. TRIPS reflects the preferences of those countries that generate intellectual property. TRIPS coverage is extensive, including copyright for computer code, cinematographic work, and performances, trademarks, geographical indicators, with special provisions for wines and spirits, and industrial designs. Patents must be issued for at least 20 y, although there are exceptions for public order, morality, and medical procedures. TRIPS requires that signatories treat foreign and national entities in the same way. These arrangements are not arrangements that the developing countries would have accepted had the status quo ante, the right to sign up to each agreement individually as opposed to the all of nothing option of the WTO, still been available.

Structural power.

For most American students of international politics, structural power is a more elusive concept than compulsory or institutional power, both of which operate through identified agents. Structural power refers to the mutual constitution of actors, which occurs sometimes in a symmetrical relationship but more often in a hierarchical one. Actor constitution involves instantiating capacities, interests, and self-understanding. Rather than the constraints that might be imposed by compulsory or institutional power, structural power is enabling. It makes it possible for social entities to act in specific, albeit it sometimes limiting, ways. Slaves have a defined but constrained role (ref. 7, p. 53).

The most important example of structural power in the international system is the universal embrace of sovereign statehood as the only legitimate form of political organization. Although sovereignty has always been characterized by organized hypocrisy—this essay shows that nonintervention, the basic rule of Westphalian/Vattelian sovereignty, has frequently been violated—there is no accepted alternative to sovereignty (ref. 6, p. 99). The many different political forms that were recognized before the 20th century—empires, tributary states, protectorates, dominions, colonies, and tribes—no longer have formal standing in the international system. All states are recognized as being equal. Ultimate formal juridical authority rests with the state even if the de facto authority of nonstate actors is more significant. Protectorates such as the Marshall Islands exist in fact but not in name. Unlike classic empires with variegated authority claims over sometimes ill-defined territory, all states have either well-defined boundaries or well-defined territorial disputes (the islands in the South China Sea or the Durand Line between Pakistan and Afghanistan) and formally claim the exclusive authority to regulate activities within these borders.

The universal embrace of sovereignty is a manifestation of the triumph of the West—Europe and North America—over other areas of the world. East Asia offers a particularly clear example of a collision of civilizations that ended with the disappearance of a political order that had existed for millennia. The Sinocentric world, which the West encountered at the beginning of the 19th century, was radically different from the sovereign state system that had been evolving in Europe over several centuries. The Chinese centered system was based on hierarchy rather than formal state equality. China was not one political entity among many entities; it was the apex of civilization. Other polities were tributary states, offering symbolic obeisance and material tribute to the emperor. Relations among political entities within the Sinocentric world were governed by customs, rules, and rituals and not by agreements among equals. Tributary states had to adopt the Chinese calendar and send tribute missions to China at regular intervals. Aside from tributary payments and associated commercial transactions, the tributary system also provided for the investiture of the tributary state ruler by representatives of the emperor. Such ceremonies legitimated the local ruler. From the Han to the Qing dynasties, for 1,500 y, China encouraged these tributary relationships (although they often imposed financial burdens on the imperial treasury), because external relations legitimated the internal position of the emperor (24⇓–26).

The sovereign state system, which originated in Europe, and the East Asian Confucian system had different norms and rules for governing external relations: formal equality for the West and hierarchy for the East, independent states for the West and tributary states and an imperial center for the East, and embassies and ambassadors for the West and tribute missions without permanent representation for the East. Although there had been ongoing contact between East Asia and Europe since the 16th century, these two cultures only began to clash in a sustained way during the 19th century when the West had accumulated enough military and economic power to challenge China. The outcome of this clash was the end of the Sinocentric system.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the political entities in east Asia had come to resemble those entities in other parts of a world system that were dominated by the West. China's tributary states had become colonies of the European powers or Japan; by 1960, they would be independent states. Japan, after the Meiji restoration, had embraced Western institutional forms both internally and externally to prevent subjugation. China itself had become an international legal sovereign with embassies, ambassadors, and international treaties, all institutional forms totally alien to the traditional Sinocentric world.

China's conception of its own interests has been transformed. In 1793 the court of the Emperor Qian Long was obsessed with whether the British emissary, Macartney, would follow established ritual practices. Macartney wanted to describe the goods that he was bringing as gifts; the Chinese wanted to describe them as tribute. The Chinese wanted Macartney to kowtow to the Emperor. The Chinese records claim that Macartney did kowtow; Macartney claimed that he did not, bowing to the Emperor as he would to the British king. The Emperor rejected British requests for a permanent embassy in Beijing and described the idea of Chinese representatives in Europe as “utterly impractical” (27, 28).

Today, China is the staunchest major power defender of the conventional rules of sovereignty. China has made nonintervention in the internal affairs of other states one of the cornerstones of its international diplomacy. It has been more reluctant than any other state, perhaps save Russia, to support UN resolutions authorizing the use of force.

The spread of the sovereign state system over the last two centuries is a compelling example of structural power. A set of practices that had evolved in the West over several hundred years has been globally embraced even in places where it is far from clear that sovereignty offers the most stable or effective form of governance.

Productive power.

Productive power constitutes actors, their interests, capacities, and self-understanding through indirect and networked discourse. These discourses make certain kinds of actions and behavior acceptable and others almost unthinkable. “In general,” Barnett and Duvall (7) argue, “the bases and workings of productive power are the socially existing and, hence, historically contingent and changing understandings, meanings, norms, customs, and social identities that make possible, limit, and are drawn on for action” (ref. 7, p. 56).

One body of literature that shows how productive power can reverse the second image (how the global environment can alter domestic authority structures) is world polity institutionalism. World polity institutionalism holds that states are embedded in a global network that defines proper state identity. International organizations, international nongovernmental organizations, and professional organizations propagate concepts of appropriate state organization and behavior. For many functions, all states claim to do more or less the same thing. States want to be modern, and in the contemporary world polity modernity is associated with a specific set of activities. There is surprising uniformity in the way in which states are organized. Virtually every state has an education ministry, a health ministry, and a national science foundation (even states with no scientists) (29). Virtually all states have mandates for social safety nets and minimal levels of education. The network generates notions of appropriate state behavior through discourse. States that are more embedded in these networks are more likely to adopt generally accepted institutional forms (30, 31).

A global discourse led by international organizations, international nongovernmental organizations, and national aid agencies has legitimated certain forms of state authority and delegitimized others. States must have a ministry of health but not a ministry of eugenics. States must have an army, a navy, and an air force (sometimes even states like Bolivia with no seacoast), but they do not necessarily have a heavily armed police force like the Italian carabinieri. The scope of authority appropriate for a modern state is defined by a discourse that makes no distinctions among states. The extent to which this discourse is accepted by a particular state depends on how much it is embedded in a network of global discourse: North Korea is hardly at all embedded, whereas South Korea is deeply embedded.

Productive power can also operate in regional and bilateral contexts. The EU has offered potential members not only the prospects of greater trade and investment, financial assistance, and higher economic growth but also a different identity, a European identity that would be available to their citizens. The EU flag, along with those of France and Germany, flies over the memorial at the Verdun battlefield where more than 300,000 soldiers died in 1916, a symbolic statement that would have been unimaginable in say the late 1930s or even the late 1940s. Even more specifically, engagement with other states can change the self conception of actors within a state, including the military. In Europe, NATO membership not only required that the military be subject to civilian rule but also offered a model that helped to soften the resistance of militaries in some southern European states, notably Spain. There is also some evidence that the professional military training programs conducted by the United States make participants not only more sympathetic to democratic values but also provide them with a new understanding of their role as professional military officers (ref. 12, p. 528 and ref. 32, p. 340).

Conclusion

Institutions are key elements of all human societies. Most of our approaches to understanding persistence and change in institutions are based on voluntary choices, determined either by values or material interests. The actors making these choices are themselves subject to these institutions. In political science, more attention has been given to the impact of coercion and power, but attention to the impact of external actors on state structures has, until the last decade or so, been modest. This conventional assumption of state autonomy is problematic. States may bargain over their domestic authority structures and not just policies. In addition, weaker states have been subject to compulsory, institutional, structural, and productive power. Weaker states have been at the receiving end of invasions, asymmetrical bargaining, pressure from international organizations, and global discourses dominated by entities from modern industrialized states. The very fact that these weak states exist in the first place reflects the structural power of the West, the extent to which sovereignty is the only universally recognized way to organize political life (33). Lake (14) has argued that “the assumption that sovereignty is indivisible is not warranted. By preventing analysts from seeing hierarchy between states, it actually has a pernicious effect on the study of international relations” (ref. 14, p. 50). That effect is weakening. Four different ways of thinking about power—compulsory, institutional, structural, and productive—as well as bargaining offer a typology for classifying how external actors might influence domestic authority structures in target states.

1. Gourevitch P (1978) Second image reversed: The international sources of domestic politics. Int Organ 32:881–912.

2. Waltz K (1954) Man, the State, and War: A Theoretical Analysis (Columbia University Press, New York).

3. Waltz K (1979) Theory of International Politics (Addison–Wesley, Reading, MA).

4. Tilly C (1990) Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1990 (Basil Blackwell, Cambridge, MA).

5. North D, Weingast B (1989) The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. J Econ Hist 49:803–832.

6. Krasner S (2003) The hole in the whole: Sovereignty, shared sovereignty, and international law.Mich J Int Law 25:1075–1101.

7. Barnett M, Duvall R (2005) Power in international politics. Int Organ 59:39–75.

8. Gruber L (2000) Ruling the World: Power Politics and the Rise Of Supranational Institutions(Princeton University Press, Princeton).

9. Moravcsik A (2000) The origins of human rights regimes: Democratic delegation in postwar Europe.Int Organ 54:217–252.

10. Simmons BA, Danner A (2010) Credible commitments and the international criminal court. Int Organ 64:225–256.

11. Pevehouse J (2002) Democracy from the outside-in: International organizations and democratization. Int Organ 56:515–549.

12. Mansfield E, Pevehouse J (2006) Democratization and international organizations. Int Organ60:137–167.

13. Levy PI (2009) The United States-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement: What Did You Expect?(American Enterprise Institute, Washington, DC).

14. Lake DA (2009) Hierarchy in International Relations (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY).

15. Matanock A (2010) Even States Share: Governance Delegation Agreements (Stanford University,Palo Alto, CA).

16. Why RAMSI Was Formed? Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands. Available athttp://www.ramsi.org/about/history.html.

17. Owen JM (2010) The Clash of Ideas in World Politics: Transnational Networks, States, and Regime Change, 1510–2010 (Princeton University Press, Princeton).

18. Peceny M (1999) Democracy at the Point of Bayonets (Pennsylvania State University Press,University Park, PA).

19. Bueno de Mesquita B, Downs GW (2006) Intervention and democracy. Int Organ 60:627–649.

20. Pickering J, Peceny M (2006) Forging democracy at gunpoint. Int Stud Q 50:539–559.

21. Lo N, Hashimoto B, Reiter D (2008) Ensuring peace: Foreign-imposed regimes change and postwar peace duration, 1914–2001. Int Organ 62:717–736.

22. Peic G, Reiter D (2011) Foreign-Imposed Regime Change, State Power, and Civil War Onset,1920–2004, B J Pol S 41:453--475.

23. Dwan R, Bailey L (2006) Liberia's Governance and Economic Management Assistance Programme (GEMAP): A Joint Review by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations' Peacekeeping Best Practices Section and the World Bank's Fragile States Group. Avaialable athttp://www.peacekeepingbestpractices.unlb.org/PBPS/Library/DPKO-WB%20joint%20review%20of%20GEMAP%20FINAL.pdfAccessed June 29, 2011.

24. Chen T (1968) Investiture of Liu-Ch'iu kings in the Qing period. The Chinese World Order: Traditional China's Foreign Relations, ed Fairbank JK (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA).

25. Fairbank JK (1968) A preliminary framework. The Chinese World Order: Traditional China's Foreign Relations, ed Fairbank JK (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA).

26. Kim K (1980) Korea, Japan, and the Chinese Empire, 1860–1882 (University of California Press,Berkeley, CA).

27. Emperor Qian Long Letter to George III. Available athttp://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/core9/phalsall/texts/qianlong.html. Accessed June 29, 2011.

28. Peyrefitte A (1993) The Collision of Two Civilisations: The British Expedition to China in 1792–1794(Harvill, London).

29. Finnemore M (1993) International organizations as teachers of norms: The United Nations educational, scientific, and cultural organization and science policy. Int Organ 47:565–597.

30. Meyer JW, Boli J, Thomas G, Ramirez FO (1997) World society and the nation-state. Am Sociol Rev 103:144–181.

31. Koo J-W, Ramirez FO (2009) National incorporation of global human rights: Worldwide expansion of national human rights institutions, 1966–2004. Soc Forces 87:1321–1353.

32. Ruby TZ, Gibler D (2010) US Professional Military Education and Democratization Abroad. Eur J of Int Rel 16:339–364.

33. Jackson RH, Rosberg CG (1982) Why Africa's weak states persist: The empirical and juridical in statehood. World Polit 35:1–24.

Krasner, Stephen. “Changing state structures: Outside in.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, December 2011

The full text of this publication is available via Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.