Introduction

China’s overtures have been met with suspicion in the Arctic states, where some analysts and commentators read nefarious intent into Chinese actions and statements. China’s construction of critical infrastructure and investments in the strategically located and resource-rich Arctic have raised concerns about national security. This is particularly the case in the seven out of eight Arctic states (excluding Russia), all of whom are now members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). What is more, questions abound about the dual-use applicability of Chinese research activities in the region.1

The Arctic is a highly strategic location, and activities here are often framed in geopolitical terms. In an era of intensifying great power competition between the United States and China, this suspicion has generated several core narratives2 about China’s Arctic interests and its engagement with and in the region.

Xi Jinping launched China’s Belt and Road Initiative3 (BRI) in 2013. The initiative envisages interconnectivity across the Eurasian continent, primarily from China to Europe. Since then, the project has expanded to other areas of the globe, including the Arctic region. The Arctic region was officially made a part of the Belt and Road Initiative via the Maritime Cooperation Vision statement (“一帶一路”建設海上合作設想).4 Later, China established the Polar Silk Road (冰上丝绸之路) in its 2018 Arctic Policy White Paper5 connecting Asia and Europe through the Arctic Ocean.

In the 2018 White Paper, the State Council of the PRC refers to its country as a “Near-Arctic State,” a statement that has remained highly controversial. While the White Paper emphasizes the Chinese government’s commitment to peaceful cooperation in the region, as well as a desire to contribute to Arctic research, protection, and development in accordance with international law, it also articulates Beijing’s aim of increasing its participation and influence in Arctic governance. It further iterates Beijing’s responsibility for maintaining security and stability in the region as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. China became an observer to the Arctic Council in 2013; since then it has contributed to scientific knowledge through research stations and expeditions, invested in Arctic business and competence, engaged in infrastructure projects, traded with Arctic states, and participated in multilateral international agreements such as the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement.6

Chinese Arctic ambitions and activities are contentious. Commentators in the seven Arctic states often frame Chinese investments in an adversarial way, describing Chinese activity in alarmist language in terms of scale, scope, and risk. Analysts have the tendency to mix proposed investments with actual investments. For example, some analysts estimate that Chinese investments in the Arctic top $90 billion7 and call this level of investment “unconstrained.”8 According to one mainstream narrative, China will use this “inflow of investments”9 to increase its influence among Arctic nations by means of debt-trap diplomacy.10 Our research finds that these numbers are highly exaggerated and often mobilized to support a narrative in which China is successfully “buying up” the Arctic region, but that these inflated numbers include unsuccessful investment projects and proposed projects that have not been implemented.

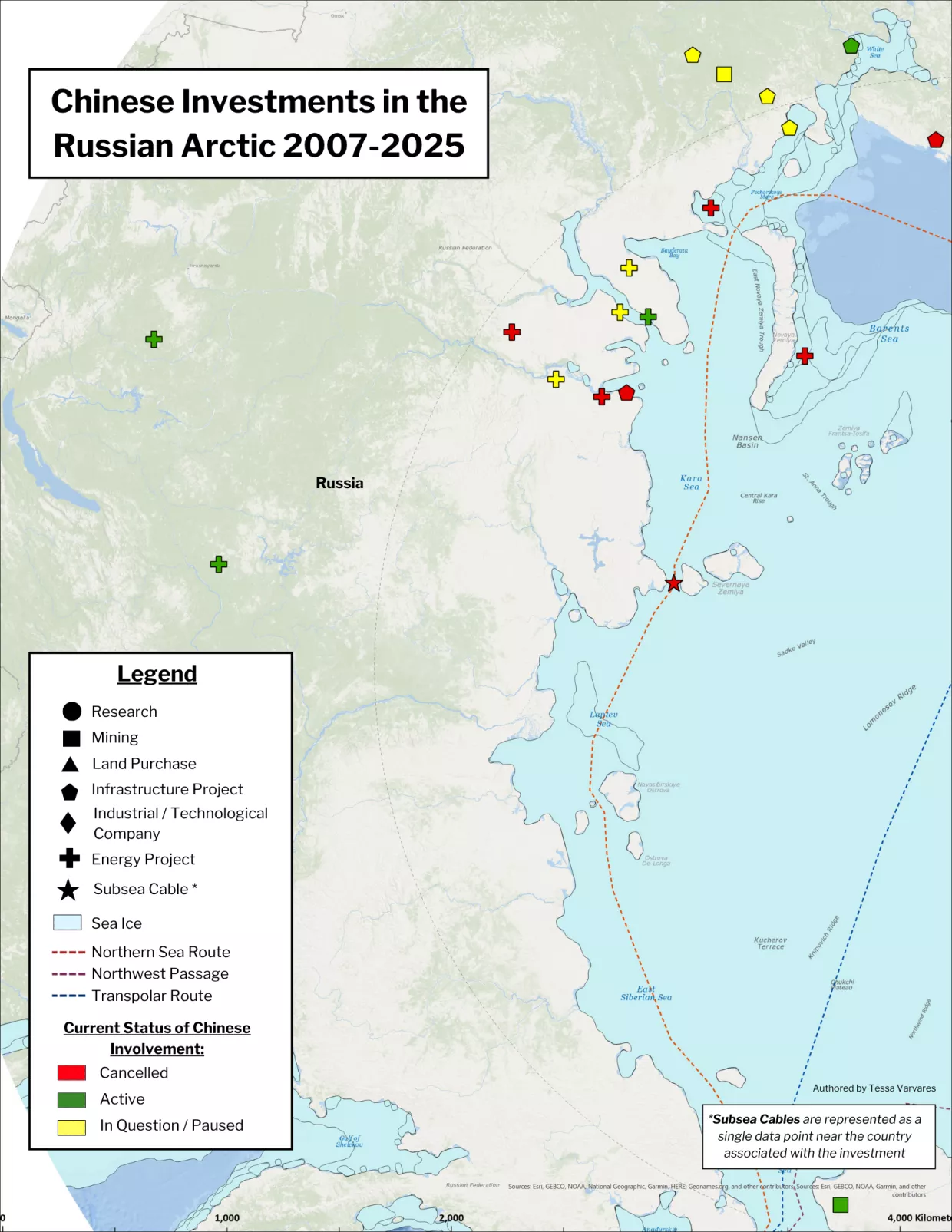

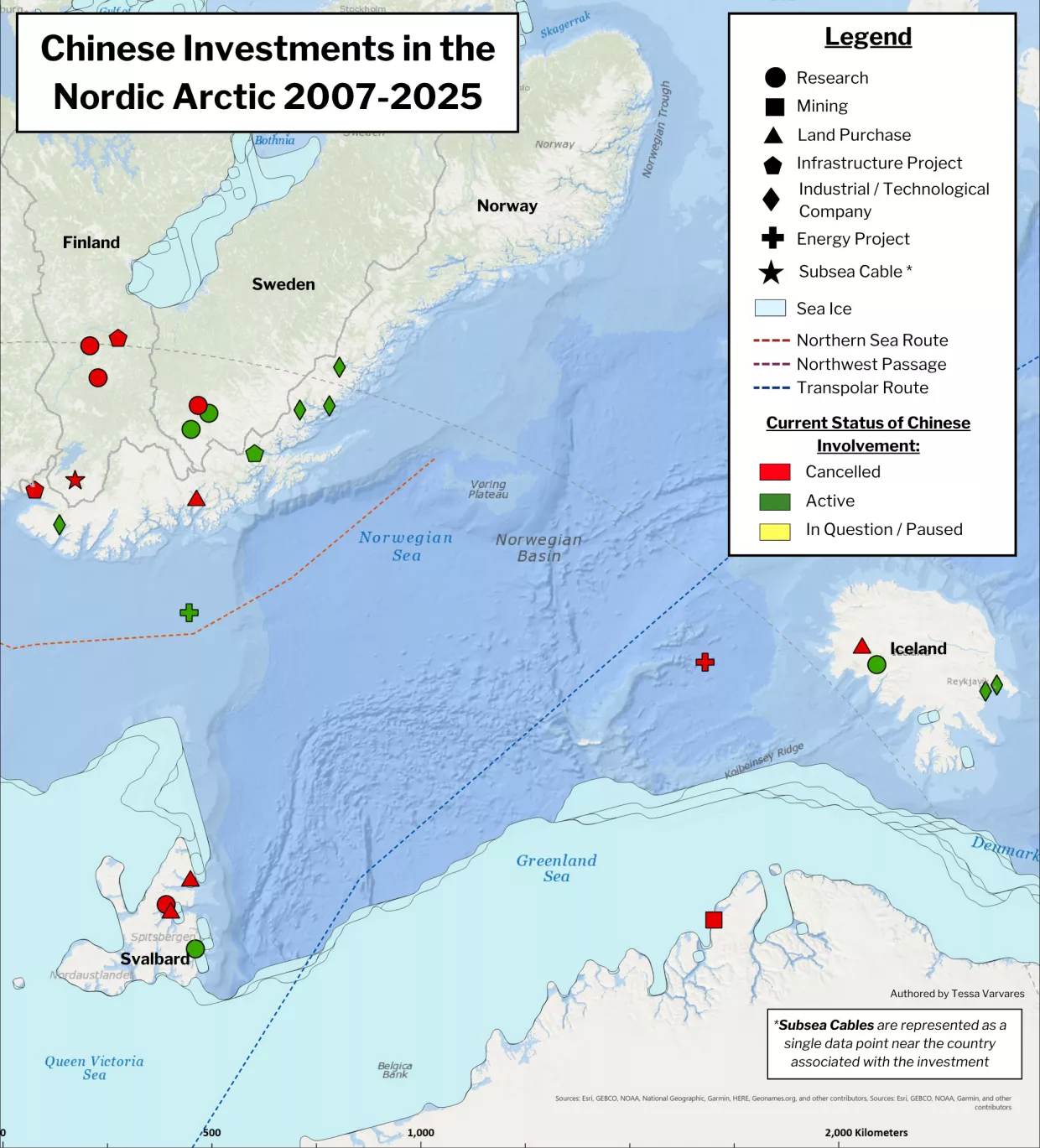

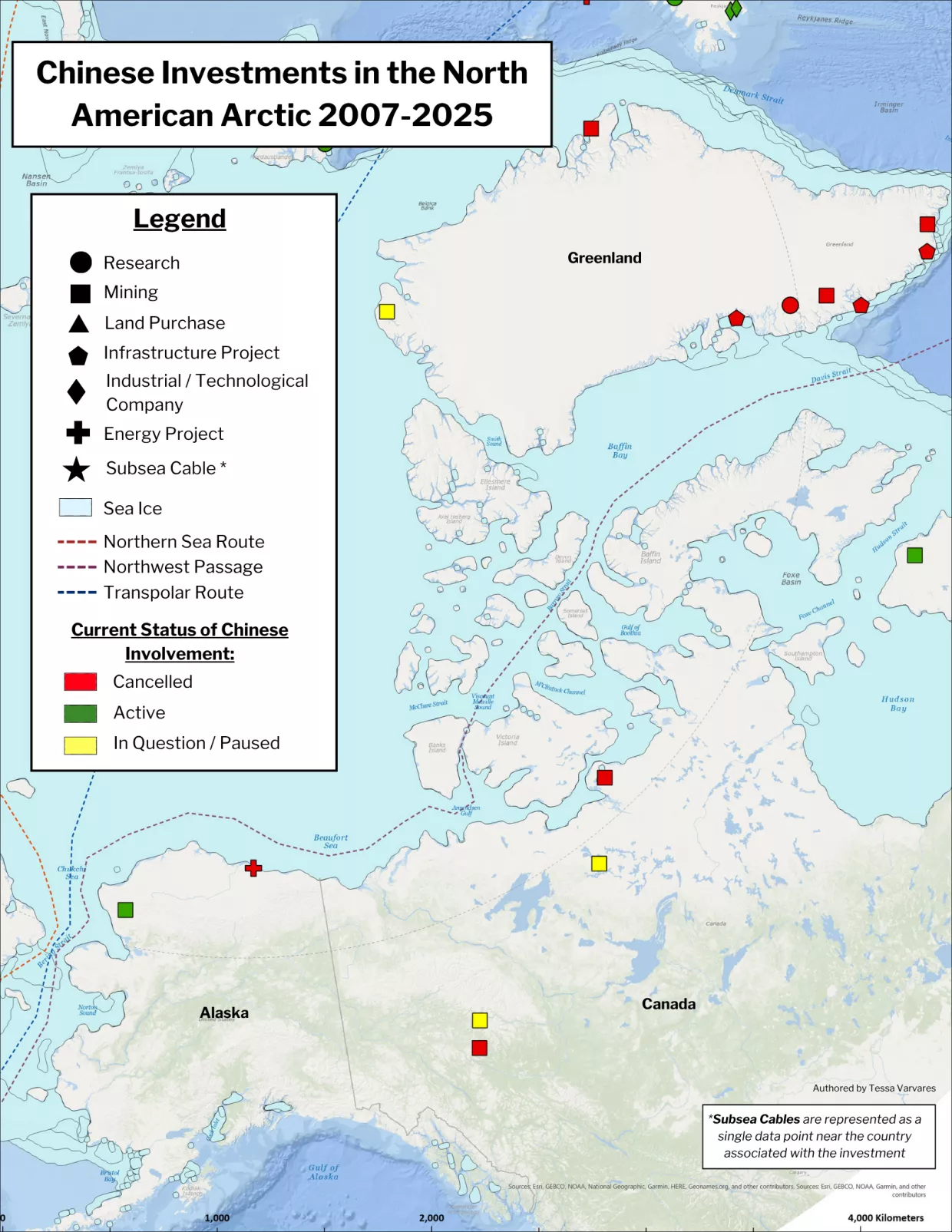

To facilitate informed debate and decision-making, this policy paper attempts to outline, although not to summarize, the actual level and state of Chinese ownership in the Circumpolar Arctic. To help illustrate our findings, we present a map displaying geographical locations of investment interests (See Figure 1), containing two further information layers. The first information layer displays the type of known Chinese interests in the Arctic, and the second information layer indicates whether this interest materialized, is paused/in question, or has been cancelled. For further description of our mapping methodology, see Appendix A.

We use the term “investment” generously in this brief, including traditional foreign direct investment (FDI) according to established definitions, but also other modes of Chinese economic engagements. We have relied on open-source material in various languages to support our analysis, including Russian, Chinese, English, Icelandic, Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish. For a detailed description of our methodology, see Appendix A. This inclusiveness means that the amount of investments appears larger than with a more restrictive definition of FDI.

Interactive Map: Chinese Investments in the Arctic 2007-2025

Click on each point for additional information about the investment.

Russia

Due to Western economic sanctions, Russia views China as a necessary economic partner to develop its Arctic. While Russia and China have cooperated on large investments in oil and gas production and infrastructure construction, several proposed projects have not panned out.

Russia and China have been increasing their cooperation in the Arctic. Days prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the two states signed a joint statement proclaiming that their relationship knew “no limits.”11 This “limitless” relationship has since expanded to include a memorandum of understanding on joint oversight of traffic12 along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), joint naval and coast guard exercises13 in the Bering Sea, and joint air patrols near the coast of Alaska.14

The two countries have had a troubled history15 characterized by conflicts along their borders and mutual suspicion, as well as cooperation. Russia was skeptical about allowing China to become a permanent observer to the Arctic Council,16 for example. Only after the criteria for admitting observers were clarified to specifically require recognition of the sovereignty and jurisdiction of the Arctic states in the region did Russia consent to extending this status to China.17 Following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia significantly relied on China as a necessary partner to develop its Arctic and manage the challenges created by Western sanctions.18 Various friction points19,20 remain in the Sino-Russian Arctic partnership that should not be overlooked, even as the two countries strive to tighten their relationship.

Russia has by far the largest amount of Chinese Arctic investments of all the Arctic states. The most notable is the Yamal LNG (liquified natural gas) project which supplies European and Asian markets with gas by Arctic-class LNG carrier ships. The project, worth 27 Bn USD,21 is as of 2016 majority owned22 by the private Russian company Novatek OAO, together with China National Petroleum Company (CNPC, 20%), French oil company Total (20%), and the Chinese Silk Road Fund (9.9%). This investment also included a series of loans23,24 from major Chinese financing institutions and serves as the primary example of Chinese investment in the Arctic region. After President Putin opened the facilities,25 the project began to ship LNG from the Port of Sabetta to foreign markets, including Europe,26 despite economic sanctions following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The Arctic LNG 2 project, a subsequent investment next to Yamal on the Gydan peninsula, is 20% owned by a Chinese company27 and has met with challenges due to U.S. sanctions, culminating in a force majeure28 issued by the investing parties in late 2023.

Other examples of Chinese investments in Russia are the 4,188 km-long Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline29 which supplies Russian crude oil to the Asia-Pacific, and the 5,111 km-long Power of Siberia pipeline30 which supplies natural gas from Russia to China. Negotiations over the Power of Siberia II from the Arctic to China are stalled due to disagreement over price,31 with China insisting on what Moscow perceives to be unrealistic price and supply levels.32

Russia tried to attract Chinese investors in 2015 for the Vankor oil fields33 in Eastern Siberia but failed to do so. Chinese participation in the Payakha Oil and Gas Field project was, however, announced in 2019 following the signing of a cooperation agreement34 between China National Chemical Engineering Group Co., Ltd. and the previous project owner Neftegazholding. The agreement involved the Chinese partner as a contractor with responsibility for processing equipment, terminals, a pipeline and a power plant. The extensive project was expected to take four years and be put into production in 2023.35 The field was sold to Rosneft in 2021,36 and is now under the auspices of the Vostok Oil Project. The current status of the Chinese involvement remains unclear.

The Vostok Oil Project,37 developed by Rosneft, is a vast initiative envisioning the establishment of a new oil region on the Taimyr Peninsula. The project serves as an umbrella for various projects at different stages of development, including field, pipeline and port development. The project aims to develop four oil fields, establish a connection between the fields and markets by constructing the Vankor-Payakha-Bukhta Sever oil pipeline38 and the Bukhta Sever port terminal for shipping along the NSR. Reports indicate that the pipeline was more than 25% constructed in 2023, and port construction started in 2024.39 The Russian Deputy Minister invited China40 to participate in the Vostok project the year before, after foreign partners had pulled out of the project. Nevertheless, China has yet not been willing to invest in the overall project.41

China has also engaged in other infrastructure projects along the Polar Silk Road or NSR. The Belkomur railway, an oft-discussed example of Chinese-Russian partnership, proposes to link the Russian internal Urals with the ports of Indiga and Arkhangelsk.42 Although there is a will and need for this rail connectivity,43 there is not enough money for the project at present. In 2017, China’s Poly International showed interest44 in investing in Lavna Coal Terminal in Murmansk. Although the investments were proclaimed,45 Chinese investors were not listed among the investors in the project.46,47 Another unsuccessful endeavor started in 2013, with China’s CNPC signing an agreement48 with Rosneft to explore the Barents and Pechora Seas for oil. CNPC later assessed too many risks49 in the project and terminated its involvement.

In 2023, China Communications and Construction Company entered into discussions with Russian Titanium Resources (Rustitan) to develop the Pizhemskoye mining project in the Komi Republic.50 The project also relates to the expansion of the deepwater port of Indiga51 as well as construction of a railway connection for Sosnogorsk-Indiga. The project is projected to begin in 2026, and would supply the Chinese market with titanium and various minerals.52,53 As it stands, however, the project has not been implemented.

China and Russia initiated discussions of a subsea cable called ROTACS that would link China, Japan, Russia, and the UK via the Arctic Ocean.53 Russia later abandoned this project.55

The Nordics

Out of the seven like-minded Arctic States, the Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland) have been most prominently engaged with China. Although China has been involved in investments, energy projects, and scientific research in the Nordic Arctic, many projects have stalled or failed in recent years.

The Nordic countries have a tradition and history of being open to trading with the world and of supporting strong institutional frameworks of international law. Norway, Iceland, Sweden, and Finland have different trade and investment circumstances that shape their economic relations with China. Sweden and Finland belong to the agreement frameworks of the European Union (EU). Norway and Iceland, on the other hand, navigate more independently but are associated with the EU through the European Economic Area and European Free Trade Association.

Iceland was one of the first countries to recognize Chinese market economy status in 2005, and in 2013 was the first country in Europe to sign a free-trade agreement with China. Norway was in a tight race with Iceland to negotiate such an agreement, but the awarding of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo56 caused China to freeze relations with Norway for six years until the two countries normalized bilateral relations.57,58

Several Nordic companies have attracted Chinese investment. According to the Global Investment Tracker, from 2005 to 2024, a total FDI amount of 7.78 Bn USD was invented in Norway, 16.94 Bn USD in Sweden and 17.35 Bn USD in Finland.59 Many of these investments were made in the southern parts of these countries, and thus are not relevant to our discussion. The Global Investment Tracker does not consider Iceland to have any Chinese FDI, although our research suggests otherwise.

Finland and China started discussions to build the Arctic Connect Subsea Cable, a 10,500 km-long fiber optic cable via the Arctic Ocean, in 2017.60 The project would have been implemented by Cinia Group, a Finnish government-owned communications and technology firm that was open to partnering with China Telecom. The project was later halted,61 and Finland launched discussions for the Far North Fiber cable with the United States instead.62

In 2011, Chinese property developer Huang Nubo bid to buy Grímsstadir á Fjöllum, a large section of land in northeastern Iceland, for tourism purposes.63 The initiative caused controversy owing to general concerns about foreigners owning Icelandic land rather than questions of security per se.64,65 Proponents argued that the project would provide economic opportunities to a remote region,66 while others worried that the Chinese state was using this project to secure a foothold for access and influence in the Arctic. The Icelandic government ultimately rejected Huang’s bid.67

The same investor subsequently attempted to buy a square kilometer of property for tourism development in Lyngen, Norway in 2014.68 There is no indication that the purchase was approved. Huang was unable to buy land in Austre Adventfjord in Svalbard in 2014, with the Norwegian government purchasing it instead two years later.69 When the last privately held property in Svalbard, Søre Fagerfjord, was put up for sale in 2024,70 the Norwegian Security Services and authorities warned against a sale to China, and the Norwegian Government retains the right to veto any such action.71

From 2014-2018, the third largest national oil company in China, China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), received licenses and entered into partnerships with Eykon Energy and Petoro for exploring for oil and gas on the Dreki field on the Icelandic continental shelf.72,73 This venture was eventually halted.74 The Finnafjörður harbor project in Northeastern Iceland has often been named in connection to the Dreki oil field exploration.75,76 In 2011 and 2012, Iceland’s then Minister for Foreign Affairs said Iceland and China were discussing the possibility of cooperating on the project, but also named other nations’ interests, including Singapore and Dubai.77 Icelandic diplomats visited China to discuss the project in 2012.78 Locals are still interested in developing the project and see it as having tremendous economic potential.79 The project never took off with Chinese partners, however, but the German company Bremenports has signed an MoU with Icelandic partners to construct the harbor and remains interested in developing the port.80

In Narvik, Norway, the Chinese infrastructure construction company Sichuan Road and Bridge won the contract for the Hålogaland Bridge in 2013,81 which the company saw as an entry ticket to the European market.82 The bridge was constructed by predominantly Chinese workers with Chinese building materials, and was opened by Prime Minister Erna Solberg in 2018.83 During construction and after completion of the bridge, delays,84 and issues with building materials85 have generated contractual disputes. Despite the challenges, the Chinese media touts the bridge as a significant link for the region and a foundation for further exploring the European market.86

The only investment defined as a foreign direct investment (FDI) in Iceland was the 2015 Geely Group investment of 45.5 million USD in the industrial/technological company Carbon Recycling International.87 In 2024, CRI commissioned a third facility in China using its proprietary Emissions to Liquids technology.88 Indirectly, a FDI investment was made when Chinese Bluestar purchased the Norwegian industrial/technological silicone producer Elkem in 2011, reportedly acquiring 100% ownership for about 2 Bn USD. The investment provides ownership over plants, mines, and offices around the world89: one in Iceland and 14 locations in Norway.90 The northern sites are marked on the map, with this one investment constituting the majority of the green markers in Norway, giving the impression that there are many Chinese investments in Norway connected to the Arctic. Elkem was later relisted on the Oslo Stock Exchange as Elkem ASA in 2018, with Chinese Bluestar retaining 61.8% ownership.91

Other Chinese investments in Norway are headquartered outside of the Arctic but run operations within the Arctic. For example, in 2016 a state-owned Chinese company purchased 40% of the fast ferry construction and technology firm Brødrene AA.92 Furthermore, the Hong Kong-based investment firm China Everbright Limited owned Norwegian transportation company Boreal, which operates buses and boats in the Arctic, from 2018-2021.93

In October 2023, the signing of cooperation agreements between the Chinese state-owned company COSL with oil and gas majors Equinor94 and Vår Energi95 for exploration for oil on the Norwegian shelf caused political controversy, with the Norwegian Progress Party demanding that the government disclose the control mechanisms that ensure adherence with the Security Act.96 In December 2024, COSL found up to 52 million barrels of oil in the Barents Sea for Vår Energi, and this cooperation seems to be proceeding.97

Six Chinese companies have reportedly shown a keen interest in Kirkenes, Norway, including a prospective textile factory, car factory, technology business, investment fund, construction fund, and shipping company.98 The Chinese shipping giant COSCO has also convened discussions and meetings regarding port facility development in Kirkenes. These plans faced push back from the Norwegian Minister of Justice which, in 2024, insisted that investment plans must be coordinated with the Norwegian Security Services and can be stopped on security grounds.99 Former mayor Rune Rafaelsen (in office until 2021) dedicated considerable effort to attracting Chinese FDI to the region100 and locals resented this potential opportunity being closed off by distant political and security concerns by Norwegian authorities.101 Furthermore, the port plans in Kirkenes related to ambitions to connect the Northern Sea Route to the Finnish city of Rovaniemi by railway, enabling transportation of goods to European markets.102 These railway plans sparked interest from Chinese actors103 but were later been rejected by the Regional Council of Lapland due to concerns about impacts on Sámi culture.104

Chinese organizations have built various research facilities in the Nordics and have signaled their desire for more. Some of these projects have caused controversy, and several have been halted. Dual-use potential of these facilities, technologies and data, appears to be a primary source of concern.

China has scientific interests in the Nordic countries. Some of these research installations have been discussed in terms of dual-use capabilities, notably in a letter from the U.S. Congress select committee on the Chinese Communist Party to the U.S. Secretaries of State and Defense which expressed worries that installations in the Arctic may have functions that exceed intended peaceful research purposes.105 In the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard, the Polar Research Institute of China (PRIC) opened its Yellow River Research Station in Ny-Ålesund in 2004.106 The China Research Institute of Radiowave Propagation joined the non-profit EISCAT Scientific Association in 2007,107 operating seven sites above the Arctic Circle in Sweden, Finland and Norway.108 In 2014, with diplomatic tensions flaring between the two countries, Oslo rejected China’s request to fund and build radar antenna at the Svalbard EISCAT site in Adventdalen, outside of Longyearbyen.109

Beyond EISCAT, the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) in Sodankylä also signed an agreement in 2018 to establish a research unit and provide satellite services to the Chinese Academy of Sciences.110 The statements linked these services to ambitions under the Chinese Polar Silk Road and space-based Arctic Monitoring and surveillance of shipping lanes. Furthermore, the Polar Research Institute of China proposed a purchase or lease to further develop an airport in Kemijärvi, Finland, for Arctic research flights. The research unit and airport proposals were blocked by Finnish authorities on security grounds.111,112

China has enjoyed long-term access to space installments in Sweden. The Sweden Space Corporation (SSC) allowed access to its satellite communication antennas in Esrange in 2011, but then decided in 2020 not to renew these agreements.113 Also, the China Remote Sensing Satellite North Polar Ground Station in Kiruna was put into operation in 2016.114 The facility has also spurred discussions about the use of data for non-civilian purposes.115

Iceland hoped for positive effects from cooperation with China in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008. The China Iceland Arctic Research Observatory (CIAO) at Kárhóll in northeastern Iceland was launched in 2012,116 in part to facilitate free trade negotiations (which culminated in a Free Trade Agreement between the two countries signed in 2013).117 The CIAO research station and land are owned by the Icelandic non-profit organization Aurora Observatory (AO) and leased and operated by the PRIC for 99 years. Despite having officially started gathering data in 2013, the facilities remain under construction. This is partly due to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic as well as disagreement over covering the remaining costs of construction,118 leaving CIAO closed to the public. While some commentators see the project as an example of science diplomacy,119 given that it involves seven official research partners on the Icelandic side,120 the research station has also elicited suspicion, with some critics conceptualizing Iceland as a Chinese Trojan horse in Europe121 and others pointing to the station’s possible dual civil-military purpose.122 In March 2025, the head of the National Police Commissioner in Iceland declared that the facility has dual-use purposes and might be used for espionage.123 The Chinese embassy called the accusations “groundless” and declared that the Icelandic police should “put down its arrogance and prejudice.”124

North America

This section discusses Chinese investment interests in North America, inclusive of the United States, Canada, and Greenland (which, while part of the Kingdom of Denmark, is geographically located in the North American Arctic).

United States: While the United States receives more Chinese foreign direct investment than any other country in the world, Chinese investments in Alaska remain very limited.

According to the Global Investment Tracker, Chinese companies have invested a total of 196.42 Bn USD of FDI in the United States, making it the country with the most Chinese FDI in the world.125 Alaska has received very little Chinese investment attention, despite efforts by the first Trump administration to strike deals with China. The Chinese fund, China Investment Corp (CIC), has a roughly 10 percent stake in the Canadian mining company Teck Resources Ltd,126 which operates the Red Dog mine in Alaska. During a state visit to China in 2017, the U.S. government announced that Chinese companies had agreed to help develop the Alaska LNG project and invest up to 42 Bn USD.127 Supporters of the project hoped to create American jobs and reduce the negative U.S. trade balance with China. During Trump’s first term, the project was abandoned. The current U.S. attitude towards Chinese Arctic activities is colored by great power rivalry, culminating in Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s rebuttal of Chinese Arctic ambitions at the 2019 Arctic Council Ministerial meeting in Rovaniemi.128 The Biden administration continued to warn against increasing Chinese interest in the Arctic in the U.S. National Strategy for the Arctic Region.129

Greenland: Chinese companies, interested in Greenland’s mineral, oil, and gas resources, engaged with Greenland in the 2010s, most proposed investments have failed.

Most discussions, however, have focused on widespread Chinese interest, investment, and activity in Greenland.130 Figure 4 illustrates primary locations of Chinese interest in specific projects.

Chinese companies sought to engage in offshore oil and gas exploration, as well as in the construction of airport infrastructure in Ilulissat and Nuuk. The Greenlandic authorities have subsequently banned future offshore oil and gas exploration in their jurisdiction.131 Furthermore, the Chinese state-owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) withdrew its bid for the airport construction contracts worth a total of 3.6 Bn Danish crowns in 2019,132 after Greenland picked Denmark over Beijing to finance the planned projects the year before.

Chinese companies have had ownership, financing, and construction interests primarily in four mines (Citronen, Kvanefjeld, Isua and Wegener Halvø) related to iron, rare earths, uranium, lead, zinc and copper. Due to operator inactivity, Greenland withdrew the license of the Hong-Kong-based General Nice Group for the Isua iron mine in 2021.133 In connection with the Isua iron mine, the Chinese company had also intended in 2016 to buy the abandoned Kangilinnguit naval base from the Danish Armed Forces, but the Danish government blocked this purchase on security grounds,134 possibly following U.S. intervention.135

Chinese funding for the Citronen Fjord mine was replaced with U.S. funding in 2021136 (under the U.S. government’s 402A program137 that lends money to companies so that they can compete with China). The Australian project owner Ironbark Zinc has subsequently also reached a non-binding MoU with the Norwegian contractor Leonhard Nilsen & Sønner AS.138 The status of the competing and non-binding construction contract139 with China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group remains unknown.

Leshan Shenghe Rare Earths entered into a partnership with Greenland Minerals in 2016 for the Kuannersuit/Kvanefjeld project, and currently holds a 12.5% stake140; Shenghe announced to the Chinese stock exchange that is has contractual rights to increase its stake to 60%, but this claim was repudiated by Greenland’s Ministry of Mineral Resources. Because the Kvanefjeld field contains high concentrations of uranium in addition to the rare earths and valuable minerals, the Greenlandic government’s 2021 decision to ban mining of uranium141 makes the future of this potential mine highly improbable. Investment interests in the copper mine Wegener Halvø were held by a conglomerate of ownership interests named Jiangxi Union Mining,142 until the Chinese companies gave up on the project and the license expired in January 2019.

In terms of research cooperation and stations, the State Oceanic Administration of China and the Greenlandic Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and the Church of Greenland signed a MoU in 2016 which opened space for joint research efforts, sharing data and consideration on cooperation on research stations in Greenland.143 On May 30, 2017, Cheng Xiao, Dean of the Global Institute of Beijing Normal University; Karl Zinglersen, Researcher of the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources; Flemming Enemark, Director of TELE-POST (the largest telecommunications service provider in Greenland); and domestic representatives officially launched plans for a remote sensing satellite ground station and research project in Greenland.144 Journalists noted that this project had been announced without the knowledge of the Greenlandic authorities empowered to approve such plans.145 Accordingly, there are no signs that the plans have been enacted, and the project appears to have halted.

Canada: With the exception of one nickel mining project, all Chinese investments in the Canadian Arctic have either failed or have been in abeyance for many years.

The Canadian government continues to weigh the threats and opportunities that China’s Arctic interests and investments pose. Shandong Mining’s 2020 attempt to purchase northern gold mining firm TMAC, owner of the Hope Bay Gold Mine, attracted extensive Canadian national media coverage. The national security review from the Government of Canada that rejected the offer under the Investment Canada Act (ICA) reinforced concerns about pernicious Chinese influence in the region,146 which weigh heavily on Canadian regulators.

China currently has a small footprint in northern Canada, its companies owning only one mine and two advanced development projects there (defined as north of 60° and Inuit Nunangat). The only operating Chinese-owned mine in the Canadian North is the Nunavik Nickel project147 on the Raglan Peninsula in northern Quebec, which produces nickel, copper, platinum, and palladium and is owned by Canadian Royalties Inc., a subsidiary of Zhongze Holding Group Co., Ltd. (ZHG). In 2014, Jilin Jien Nickel Industry Co. (part of ZHG) spent $735 million building the mine and the accompanying infrastructure,148 and the first mineral shipment was sent to China through the Northwest Passage that same year.

Chinese companies also own two major development properties. The Selwyn Lead and Zinc Project in the Yukon – one of the largest undeveloped zinc-lead deposits in the world – is owned by Yunnan Chihong Zinc and Germanium Co., a state-owned firm, and managed by Selwyn Chihong Mining Ltd, a Canadian subsidiary.149 Low resource prices slowed development, and no significant progress has been made since 2015. The larger Izok Lake project in Nunavut, owned by Chinese state-owned MMG, includes plans for a copper and zinc mine and mill.150 Ambitious plans for extensive infrastructure, including a port, were halted in 2013 in the face of declining resource prices. There is no guarantee that the Grays Bay Road151 will be built, or that it will lower costs sufficiently to enable MMG to bring its projects into production.

China’s investment record in the Canadian North is not strong, and Chinese companies have also seen significant failures. The Wolverine mine in Yukon is a prime example. Purchased by state-owned Jinduicheng Molybdenum Group Co., Ltd. for $113 million in 2008, the zinc, copper, and lead concentrate mine went into production in 2012 and closed in 2015.152 Called an “irresponsible mining venture” by one Yukon judge,153 the assets were taken over by the Yukon in 2018 after the Yukon Zinc Corporation declared bankruptcy and transferred from its Chinese parent to MinQuest, an American holding Company. The Lac Otelnuk iron ore project in northern Quebec was also funded by Wuhan Iron and Steel through a joint venture from 2012 to 2015,154 but the project failed and was placed in care and maintenance in 2016. Thus, with the exception of Jilin Jien Nickel Industry’s investment in the Nunavik Nickel project, all Chinese investments in the Canadian Arctic have either failed or have been in stasis for many years. It is no surprise, therefore, that the trend in Chinese investment has slowed since 2016.

Conclusion

This policy brief has mapped cases of circumpolar Chinese economic activity, as well as research stations, infrastructure construction and ownership, energy projects, and mining. Some cases can be labelled as FDI according to traditional definitions, while others must be defined differently. We have not included portfolio investments, which we consider to be less strategic in nature, in this brief.

The Chinese government, companies, and organizations have communicated their ambitions and plans for investments in the Arctic region, but only a small proportion of these have fully materialized. The reason is not entirely due to Chinese investors and economic foundations. We observe a range of complex reasons that have hindered their realization, including geopolitical and domestic political obstacles, security concerns, environmental concerns, as well as non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Accordingly, we find the following:

- Chinese interests have invested in the Arctic region and some of these projects are economically significant for their host countries. Most business investments have been completed in Russia, followed by Norway and Iceland. It would be erroneous to suggest that “nothing” is going on in the region with respect to Chinese investment.

- The scale and scope of actual Chinese investments are often exaggerated in media and public debate, and unsuccessful proposals are often taken into consideration when presenting the total amount of Chinese investment. The difference between the number of green indicators versus stalled or failed projects is striking. Most investments were concluded several years ago. Recent Chinese investment initiatives have increasingly met with headwinds in Arctic countries except for Russia. Greenland, as part of the Kingdom of Denmark, may be the best example of this. Despite Greenland receiving intensive attention in the debate about Chinese investments and influence in the Arctic, it is apparent that most of this anxiety is about what might be, not what has actually happened.

- Valuable analytical nuance is lost by discussing numbers only. The number and value of Chinese investments have become talking points for some commentators to prove the risk that China poses to the region, but the economic value and strategic value of a given asset are not always the same. We acknowledge that current debates may benefit from evaluating investments on a case-to-case basis and interrogating the strategic significance of projects through multiple lenses. For example, the amount of money that China invests in Arctic research stations and operating facilities (as shown on the map) is likely disconnected from the potential strategic value of these assets and the associated benefits to the host countries and a wider research community.

- Distinguishing between investments that pose a security risk, and those that are benign and desirable, remains challenging and can be a source of debate and division. Sometimes Chinese companies may be the only actors with the capital, competence, interest, and willingness to make an economic investment that would otherwise not be realized. Arctic states should continue to balance considerations of national interest connected to potential risk, potential economic benefits, and societal support before deciding to allow, limit, or reject investments.

In conducting this research, we recognize there is need for further comparative analyses with other countries to demonstrate the extent of these investments. We are currently working on furthering our analysis and welcome other expert contributions to this discussion.

Appendix A: Mapping Chinese Investments in the Arctic Region

By means of infographic maps, this brief provides an overview of proposed initiatives and stated interests, and the progress of their implementation. We have categorized Chinese investment interests according to investment type and project status as following:

- Active (Green color): Successfully initiated or implemented investments.

- In Question/Paused (Yellow color): Proposed investments which have stalled due to considerable challenges or status remains in question.

- Cancelled (Red color): Investments which were unsuccessful.

Listed interests are ownership of companies, land purchases, involvement in energy projects, infrastructure construction and research station ownership, partnerships, and operations. In the second map, the colors green, yellow and red are used to indicate project success. If a project is fully implemented as planned, or runs along a steady development plan, the project is marked as green on the map. If the project has encountered sizing down or uncertain future development, the project is marked as yellow on the map. Third, if the investment process has been halted or project implementation appears unlikely, the project is marked as red on the map.

In locating the investments, we found that some were geographically difficult to pinpoint to a single location, such as pipelines and submarine cables that span a long distance. In such instances, the investments were pinpointed to a single location, at one starting point of the piece of infrastructure.

To depict investments visually, we present a map of investment interests that displays two further layers of information. The first information layer displays the type of projects which Chinese organizations have expressed investment interests, irrespective of ownership shares or whether the projects were successfully implemented. The second information layer indicates by relevant color coding whether the projects are being concluded as planned, or whether they have met with challenges.

To discuss investments in various sections of the Arctic, we made map extractions based on geographical location. The first map extraction depicts Russia, due to its size and the number of investments. The second map extraction depicts the Nordic countries, including Svalbard. The third map extraction depicts North America and Greenland. North America and Greenland are discussed together due to geographical location and types of investment interests. In the text commenting on the investments in the Arctic region, we provide more details on the projects, as well as details on the economic involvement with the countries in general.

Mapping Chinese investments in the Arctic remains an ongoing project. In reading open-source materials, including research articles, reports, and news articles, related to Chinese overtures over the last decade, we have noted projects relevant to the overview that we have presented here. We made our utmost efforts to gather various sources in different languages, including Russian, Chinese, English, Icelandic, Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish.

Given our focus on investments with relevance in an Arctic context, we omitted investments in southern regions of the Arctic countries which have no direct Arctic footprint. How far south in each country individual investment interests should be depicted and discussed remains open to interpretation and debate, and we are open to feedback about Chinese investments further south that might be included.

This brief provides a circumpolar overview of investments but does not purport to be exhaustive. Accordingly, we welcome readers to contribute additional investment projects or details that we should incorporate into this work going forward.

Acknowledgments

Writing this policy brief has been a team effort involving many colleagues, friends, and financiers. The authors would like to extend special gratitude to the Arctic Initiative’s Dr. Jennifer Spence, Elizabeth Hanlon, and Tessa Varvares for invaluable contributions to the development of the policy brief, and for driving forward the process. Thank you also to Co-Chairs of the Arctic Initiative, Professors John Holdren and Henry Lee, as well as colleagues of the Belfer Center and Professor Frode Mellemvik of the High North Center for comments and reflections during the writing process. Finally, thank you to Dr. Marc Lanteigne for reviewing the policy brief and for reflections and detailed comments that improved the text. Mistakes and omissions in the policy brief remain the responsibility of the authors.

Work on this policy brief has been partly funded by the ArcGov project of the High North Center of Nord University Business School. The ArcGov project is part of the portfolio of the Research Council of Norway.

Edstrøm, Anders, Guðbjörg Ríkey Th. Hauksdóttir and P. Whitney Lackenbauer. “Cutting Through Narratives on Chinese Arctic Investments.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, June 23, 2025

- Letter from U.S. House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party to Antony Blinken and Lloyd Austin, October 16, 2024, https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/10.16.24_PRC%20dual%20use%20research%20in%20the%20Arctic__.pdf

- Whitney Lackenbauer and Adam Lajeunesse, “Selling the ‘Near-Arctic’ State,” Wilson Center, August 12, 2024.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative,” June 20, 2017, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/publications/2017/06/20/content_281475691873460.htm.

- Ibid.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s Arctic Policy,” January 26, 2018, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm.

- “Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean,” October 3, 2018, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/international/documents/pdf/EN-CAO.pdf.

- U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, “China Regional Snapshot: Arctic,” October 25, 2022, https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/china-regional-snapshot-arctic/.

- Mark Rosen and Cara Thuringer, “Unconstrained Foreign Direct Investment: An Emerging Challenge to Arctic Security,” CNA, November 2017, https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/cop-2017-u-015944-1rev.pdf.

- Anu Sharma, “China’s Polar Silk Road: Implications for the Arctic Region,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, Air University Press, October 28, 2021, https://www.960cyber.afrc.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2821425/chinas-polar-silk-road-implications-for-the-arctic-region/.

- U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, “Senators Highlight Greenland’s Strategic Importance, Untapped Resource Potential in Discussion About Acquisition,” February 12, 2025, https://www.commerce.senate.gov/2025/2/senators-highlight-greenland-s-strategic-importance-untapped-resource-potential-in-discussion-about-acquisition.

- Executive Office of the President of Russia, “Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development,” February 4, 2022, http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770.

- Malte Humpert, “Putin and Xi Discuss Further Deepening of Arctic Partnership,” High North News, March 23, 2023, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/putin-and-xi-discuss-further-deepening-arctic-partnership.

- Malte Humpert, “Chinese-Russian Naval Patrol Skirts U.S. Territorial Waters Off Alaska Coast,” gCaptain, October 7, 2024, https://gcaptain.com/chinese-russian-naval-patrol-skirts-u-s-territorial-waters-off-alaska-coast/.

- Matthew Adams, “Russian and Chinese Bombers Spotted Near Alaska,” Stars and Stripes, July 25, 2024, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/us/2024-07-25/russian-chinese-aircraft-intercept-alaska-norad-14594112.html

- Swedish Defence Research Agency, “China and Russia – Friends or Enemies?”, November 8, 2022, https://www.foi.se/en/foi/news-and-pressroom/news/2022-11-08-china-and-russia---friends-or-enemies.html.

- Katarzyna Zysk, “Asian Interests in the Arctic: Risks and Gains for Russia,” Asia Policy, No. 18 (July 2014): pp. 30-38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24905273.

- Yana Leksyutina, “Russia’s Cooperation with Asian Observers to the Arctic Council,” The Polar Journal, Vol. 11 (2021): pp. 136-159, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2154896X.2021.1892833.

- Iselin Stensdal and Gørild Heggelund, China-Russia Relations in the Arctic: Friends in the Cold?, Palgrave Macmillan, 2024, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-63087-3.

- Adam LaJeunesse, Whitney Lackenbauer, Sergey Sukhankin, and Troy Bouffard, “Friction Points in the Sino-Russian Arctic Partnership,” Joint Force Quarterly, No. 111 (2023), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/3571034/friction-points-in-the-sino-russian-arctic-partnership/.

- Marc Lanteigne and Whitney Lackenbauer, “’Cause It’s Always Been a Matter of Trust’: The Limits of the China-Russia Cooperation in the Arctic,” NAADSN, February 23, 2024, https://www.naadsn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/24feb23-ML-PWL-limits-china-russia-cooperation-NAADSN.pdf.

- “Novatek, Total Approve USD 27 Billion LNG Project,” Offshore Energy, December 18, 2013, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/novatek-total-approve-usd-27-billion-lng-project/.

- “Novatek and China’s Silk Road Fund Conclude Selling 9.9% Stake in Yamal LNG,” Novatek, March 15, 2016, https://www.novatek.ru/en/press/releases/index.php?id_4=1165.

- "Yamal LNG Signed Loan Agreements with the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank," Yamal LNG, April 29, 2016, https://www.novatek.ru/common/upload/doc/2016_04_29_press_release_Chinese_banks_FA_(ENG).pdf.

- "China Insurance Fund to Invest in Russia's Yamal LNG," Reuters, January 5, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/china-insurance-investment-idUSL3N14P1JG20160105/.

- “Putin Helps Launch $27 Billion LNG Plant With Russian, French, Chinese Partners,” Radio Free Europe, December 8, 2017, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-puitin-yamal-lng-chinese-french-partners/28905542.html.

- Malte Humpert, “EU Imports More Russian LNG in 2024 Than Ever Before, Mostly From Arctic,” High North News, January 6, 2025, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/eu-imports-more-russian-lng-2024-ever-mostly-arctic.

- Malte Humpert, “China Acquires 20 Percent Stake in Novatek’s Latest Arctic LNG Project,” High North News, April 29, 2019, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/china-acquires-20-percent-stake-novateks-latest-arctic-lng-project.

- Chen Aizhu and Marwa Rashad, “Exclusive: Russia's Novatek Issues Force Majeure Notices Over Arctic LNG 2 Project,” Reuters, December 21, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russias-novatek-issues-force-majeure-notices-over-arctic-lng-2-project-sources-2023-12-21/.

- “The ESPO Oil Pipeline, Siberia, Russia,” Offshore Technology, January 19, 2015, https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/espopipeline/.

- “China Completes Full Pipeline for Power-of-Siberia Gas,” Reuters, December 2, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/china-completes-full-pipeline-power-of-siberia-gas-2024-12-02/.

- Erica Downs, Akos Losz, and Tatiana Mitrova, “The Future of the Power of Siberia 2 Pipeline,” Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia SIPA, May 15, 2024, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/the-future-of-the-power-of-siberia-2-pipeline/.

- “Russia-China Gas Pipeline Deal Stalls Over Beijing’s Price Demands, Financial Times Reports,” Reuters, June 2, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russia-china-gas-pipeline-deal-stalls-over-beijings-price-demands-ft-2024-06-02/.

- “Russia’s Huge Oil Offer to China Is Truly Remarkable,” Reuters, April 8, 2015, https://www.businessinsider.com/r-learning-mandarin-in-the-tundra---russia-invites-china-into-oil-business-2015-4.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “中国化学工程签约俄罗斯帕亚哈油气田项目合作协议,” June 8, 2019, http://www.sasac.gov.cn/n2588025/n2588124/c11445784/content.html.

- Ibid.

- Anna Podlinova, “«Роснефть» назвала сумму сделки по покупке Пайяхского месторождения,” Vedomosti, February 12, 2021, https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2021/02/12/857802-rosneft-zaplatila-za-paiyahskoe-mestorozhdenie-96-mlrd-i-hvostovimi-aktivami.

- “Vostok Oil,” Neftegaz.RU, May 17, 2020, https://neftegaz.ru/tech-library/mestorozhdeniya/680427-vostok-oyl/.

- “Китаю представили российский нефтяной проект ‘Восток Ойл’,” Interfax, December 19, 2023, https://www.interfax.ru/russia/1030978.

- “Строительство нефтеналивного причала стартовало на терминале «Порт бухта Север» проекта «Восток Ойл»,” Port News, March 19, 2024, https://portnews.ru/news/360882/.

- “Китаю представили российский нефтяной проект ‘Восток Ойл’.” Interfax.

- Sergey Sukhankin, “Russia’s Arctic-Based Oil Mega-Project Struggles to Attract Foreign Investors,” The Jamestown Foundation, January 24, 2024, https://jamestown.org/program/russias-arctic-based-oil-mega-project-struggles-to-attract-foreign-investors/.

- Thomas Nilsen, “New Barents Sea Port and 500 km Railway Link Could Help Connect Asia with the Arctic,” The Barents Observer, May 27, 2020, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/arctic/new-barents-sea-port-and-500-km-railway-link-could-help-connect-asia-with-the-arctic/117314.

- “Belkomur Railroad. There Is a Will, but No Money,” Railway Supply, September 28, 2022, https://www.railway.supply/en/belkomur-railroad-there-is-a-will-but-no-money/.

- Atle Staalesen, “Murmansk Counts on Chinese Investors,” The Barents Observer, March 14, 2017, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/industry-and-energy/murmansk-counts-on-chinese-investors/135263.

- “China Invests 17 Bln Rubles into the New Murmansk Port,” SeverPost News Agency, http://severpost.com/read/152/.

- Atle Staalsen, “In Kola Bay Rises the New Lavna Coal Terminal,” The Barents Observer, May 8, 2020, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/industry-and-energy/in-kola-bay-rises-the-new-lavna-coal-terminal/137823.

- “Инвесторы занимают очередь в Лавну,” Kommersant, Novembe 29, 2018, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3813808.

- Atle Staalsen, “China to Drill in Barents Sea,” The Barents Observer, March 25, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20250119065619/https://barentsobserver.com/en/energy/2013/03/china-drill-barents-sea-25-03.

- Atle Staalsen, “Rosneft Might Have Made a Major Discovery in the Pechora Sea,” The Barents Observer, January 21, 2022, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/industry-and-energy/rosneft-might-have-made-a-major-discovery-in-the-pechora-sea/139683.

- Malte Humpert, “Russian Mining Company Partners With China to Develop Massive Titanium Deposit in Arctic,” High North News, February 6, 2023, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/russian-mining-company-partners-china-develop-massive-titanium-deposit-arctic.

- “ГК «РУСТИТАН» презентовала Мегапроект национального горнопромышленного кластера в НАО,” Sever Media, September 6, 2022, https://www.bnkomi.ru/data/news/145046/.

- “Китай заинтересован в продукции ГК «РУСТИТАН»,” Sever Media, January 3, 2023, https://www.bnkomi.ru/data/news/155348/.

- “ГК «РУСТИТАН» и «Китайская компания коммуникаций и строительства» обсудили проект освоения Пижемского месторождения в Республике Коми,” Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs,” January 20, 2023, https://rspp.ru/events/news/gk-rustitan-i-kitayskaya-kompaniya-kommunikatsiy-i-stroitelstva-obsudili-proekt-osvoeniya-pizhemskogo-mestorozhdeniya-v-respublike-komi-63ce39f4e1909/.

- Elizabeth Buchanan, “Subsea Cables in a Thawing Arctic,” The Maritime Executive, February 2, 2018, https://maritime-executive.com/editorials/subsea-cables-in-a-thawing-arctic.

- Sebastian Murdoch-Gibson, “Finland's Arctic Data Cable Set to Disrupt Global Connectivity,” Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, June 19, 2018, https://www.asiapacific.ca/blog/finlands-arctic-data-cable-set-disrupt-global-connectivity.

- “Liu Xiaobo - Facts,” NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2010/xiaobo/facts/.

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Norway, “2010 Nobel Peace Prize a Disgrace,” October 13, 2010, http://no.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zjsg_0/sgyw_134107/202309/t20230905_11138223.htm.

- “Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Kingdom of Norway on the Normalization of Bilateral Relations,” https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/departementene/ud/vedlegg/statement_kina.pdf.

- “China Global Investment Tracker,” American Enterprise Institute,” https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

- Xie Zhenqi, “China’s 10,000-km Fiber Cable to Reach the Warming Arctic,” CGTN, December 14, 2017, https://news.cgtn.com/news/7949444d32637a6333566d54/index.html.

- Thomas Nilsen, “New Trans-Arctic Pathway for Asia-Bound Subsea Cable,” The Barents Observer, December 21, 2021, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/industry-and-energy/new-transarctic-pathway-for-asiabound-subsea-cable/141661.

- “Far North Fiber,” Far North Fiber Inc., https://www.farnorthfiber.com/.

- Malte Humpert, “Iceland For Sale: Chinese Tycoon Seeks to Purchase 300 km² of Wilderness,” The Arctic Institute, September 2, 2011, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/iceland-sale-chinese-tycoon/.

- “Vilja að Grímsstaðir verði þjóðareign,” Morgunblaðið, August 31, 2012, https://www.mbl.is/frettir/innlent/2012/08/31/vilja_ad_grimsstadir_verdi_thjodareign/.

- Egill Thor Nielsson and Gudbjorg Rikey Th. Hauksdottir, “Kina, investeringer og sikkerhetspolitikk: Politikk og perspektiver i Norden – Island,” Internasjonal Politikk, Vol 78 Nr. 1 (2020), https://doi.org/10.23865/intpol.v78.2075.

- “Bæjarstjórinn er bjartsýnn,” Morgunblaðið, May 2, 2012, https://www.mbl.is/frettir/innlent/2012/05/02/baejarstjorinn_er_bjartsynn/.

- “Beiðni Huangs synjað,” Morgunblaðið, November 25, 2011, https://www.mbl.is/frettir/innlent/2011/11/25/beidni_huangs_synjad/.

- Knut-Eirik Lindblad, “Norwegian Landowner Sells Huge Amount of Land to Chinese Billionaire Huang Nubo,” Nordlys, May 16, 2014, https://www.nordlys.no/nyheter/norwegian-landowner-sells-huge-amount-of-land-to-chinese-billionaire-huang-nubo/s/1-79-7362483#am-comments.

- Atle Staalsen, “No Chinese Resort in Svalbard, After All,” The Barents Observer, October 21, 2016, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/arctic/no-chinese-resort-in-svalbard-after-all/114034.

- Thomas Nilsen, “Last Private Land on Svalbard Up for Sale for €300 Million,” The Barents Observer, May 12, 2024, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/arctic/last-private-land-on-svalbard-up-for-sale-for-300-million/122271.

- Richard Milne, “Norway Blocks Sale of Last Private Property on Arctic Archipelago,” Financial Times, July 1, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/35b7ef53-9b27-4f88-b3c9-627ab912f261.

- “CNOOC Awarded a Licence in Dreki Area Offshore Iceland,” Offshore Energy, January 22, 2014, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/cnooc-awarded-a-licence-in-dreki-area-offshore-iceland/.

- “Gefa eftir leyfi á Drekasvæðinu,” Morgunblaðið, January 23, 2018, https://www.mbl.is/frettir/innlent/2018/01/22/gefa_eftir_leyfi_a_drekasvaedinu/.

- Alma Ómarsdóttir, “Óvíst um framhald rannsókna á Drekasvæðinu,” RÚV, January 22, 2018, https://www.ruv.is/frettir/innlent/ovist-um-framhald-rannsokna-a-drekasvaedinu.

- Baldur Thorhallsson and Snaefridur Grimsdottir, “Lilliputian Encounters with Gulliver: Sino-Icelandic Relations from 1995 to 2021,” Center for Small State Studies, University of Iceland, https://ams.hi.is/en/publication/94/.

- “Siglingar á norðurslóðum – Ísland í brennidepli,” December 2019, https://ioes.hi.is/files/2021-04/Siglingar-a-norðurslodum.pdf.

- Kristján Már Unnarsson, “Segir Finnafjörð fastan í þagnarmúr ríkisstjórnar,” Vísir, April 10, 2023, https://www.visir.is/g/20232400381d/segir-finnafjord-fastan-i-thagnarmur-rikisstjornar.

- “Marorka fundaði með Cosco Group,” Vísir, October 16, 2012, https://www.visir.is/g/2012710169965/marorka-fundadi-med-cosco-group.

- Ágúst Ólafsson, “Vilja frekari aðkomu ríkisins að áformum í Finnafirði,” RÚV, December 13, 2022, https://www.ruv.is/frettir/innlent/2022-12-13-vilja-frekari-adkomu-rikisins-ad-aformum-i-finnafirdi.

- Malte Humpert, “Iceland Invests in Arctic Shipping with Development of Finnafjord Deepwater Port,” Arctic Today, April 17, 2019, https://www.arctictoday.com/iceland-invests-in-arctic-shipping-with-development-of-finnafjord-deepwater-port/.

- Thomas Nilsen, “Chinese Company to Build Longest Bridge in Northern Norway,” The Barents Observer, October 24, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20200813104259/https://barentsobserver.com/en/business/2013/10/chinese-company-build-longest-bridge-northern-norway-24-10.

- “Norsk bru blir kinesisk stålindustris inngangsbillett til Europa,” NRK Nordland, August 7, 2017, https://www.nrk.no/nordland/norsk-bru-blir-kinesisk-stalindustris-inngangsbillett-til-europa-1.13631878.

- Dou Shicong, “Built by Chinese Contractor, Norway Opens Its Second-Largest Bridge,” YiCai Global, December 11, 2018, https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/built-by-chinese-contractor-norway-opens-its-second-largest-bridge.

- Kai Jæger Kristoffersen and Ole Dalen, “Kinesisk firma bygger gigantbru i Narvik: – Forsinkelsene koster kommunen dyrt,” NRK Nordland, August 3, 2018, https://www.nrk.no/nordland/kinesisk--vant-anbudet-om-halogalandsbrua-_-na-er-den-forsinket-nok-en-gang-1.14151414.

- Petter Strøm, “Skandalebrua må stenge i ei uke fordi asfalten løsner,” NRK Nordland, September 5, 2024, https://www.nrk.no/nordland/asfalten-losner-pa-halogalandsbrua.-ma-stenges-i-ei-uke.-og-snart-ma-de-jobbe-mer-1.17031664.

- “Chinese-built Bridge Boosts Development in Northern Norway,” Xinhua News Agency, December 11, 2023, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/0N0A8H4C.html.

- Zhejiang Geely Holding Group, “Geely Group Invests in Iceland’s Carbon Recycling International in Further Step Forward for New Energy & Methanol Vehicle Efforts,” July 3, 2015, https://zgh.com/media-center/news/20150703_1/?lang=en.

- “CRI to Supply Methanol Synthesis Tech to Chinese e-Methanol Project,” Bioenergy International, October 8, 2024, https://bioenergyinternational.com/cri-to-supply-methanol-synthesis-tech-to-chinese-e-methanol-project/.

- “Quality, Plants and Locations – Global Presence and Local Production,” Elkem, https://www.elkem.com/about-elkem/corporate-structure/elkem-silicon-products/about-us/our-plants-and-locations/.

- “Elkem Norway,” Elkem, https://www.elkem.com/about-elkem/worldwide-presence/norway/.

- Zhong Nan, “Bluestar Unit Lists Shares on Norway Bourse,” China Daily, March 23, 2018, https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201803/23/WS5ab46028a3105cdcf6513c9b.html.

- Brit Jorunn Svanes, Geir Bjarte Hjetland, and Stian Sjursen Tackle, “Statseigd kinesisk selskap kjøper seg inn i vestlandsverft,” NRK, January 4, 2016, https://www.nrk.no/vestland/statseigd-kinesisk-selskap-kjoper-seg-inn-i-vestlandsverft-1.12732102.

- “China Everbright Limited Announces Sale of the Boreal Group Vauban,” Everbright Limited, November 1, 2021, https://www.everbright.com/en/news/china-everbright-limited-announces-sale-boreal-group-vauban.

- “To COSL-rigger skal bore for Equinor,” Equinor, August 31, 2023, https://www.equinor.com/no/nyheter/20230831-riggkontrakter.

- “Agreement with Vår Energi,” Rig Partner, January 30, 2024, https://rig-partner.no/agreement-with-var-energi/.

- Osman Kibar, “Enstemmig vedtak på Stortinget: Krever fullt innsyn i Equinors Kina-avtaler,” Dagens Næringsliv, October 5, 2023, https://www.dn.no/energi/cosl/equinor/kina/enstemmig-vedtak-pa-stortinget-krever-fullt-innsyn-i-equinors-kina-avtaler/2-1-1530476.

- Atle Staalsen, “Chinese Rig Finds Oil in Barents Sea,” The Barents Observer, December 16, 2024, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/news/chinese-rig-finds-oil-in-barents-sea/422160.

- Ingrid Hjellbakk Kvamstø, Inghild Eriksen, and Håvard Gulldahl, “Kinesiske gigantbedrifter vil investere i Kirkenes,” NRK, April 9, 2024, https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/investorer-fra-kina-vil-satse-i-kirkenes-og-pa-nordostpassasjen-1.16820203.

- Ministry of Justice and Public Security of Norway, “Kirkenes Port: Mehl clear that Chinese establishments may be stopped,” April 9, 2024, https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/kirkenes-havn-mehl-klar-pa-at-kinesiske-etableringer-kan-bli-stanset/id3052357/.

- Jackie Northam, “A Mayor In Norway's Arctic Looks To China To Reinvent His Frontier Town,” NPR, January 18, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/01/18/796288234/a-mayor-in-norways-arctic-looks-to-china-to-reinvent-his-frontier-town.

- Kvamstø et al. “Kinesiske gigantbedrifter vil investere i Kirkenes.”

- Atle Staalsen, “China Eyes Stake in Kirkenes Infrastructure,” The Barents Observer, June 10, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20250430144744/https://barentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2015/06/china-eyes-stake-kirkenes-infrastructure-10-06.

- Atle Staalsen, “Kirkenes Port Developers Put Their Faith in the Chinese,” The Barents Observer, June 7, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20250430144744/https://barentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2015/06/china-eyes-stake-kirkenes-infrastructure-10-06.

- Thomas Nilsen, “Lapland Regional Council Rejects Arctic Railway,” Arctic Today, May 17, 2021, https://www.arctictoday.com/lapland-regional-council-rejects-arctic-railway/.

- Letter from U.S. House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party.

- “Arctic Yellow River Station,” Polar Research Institute of China, https://en.pric.org.cn/index.php?c=category&id=98.

- European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association, “Annual Report 2019-2020,” https://eiscat.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/EISCAT-report-2019-2020_compressed.pdf.

- “Sites,” European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association,” December 13, 2024, https://eiscat.se/about/sites/.

- Lars Egil Mogård, “Norsk nei til Kina-radar på Svalbard,” NRK, September 11, 2014, https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/nekter-kina-radar-pa-svalbard-1.11927625.

- Finnish Meteorological Institute, “FMI Provides Satellite Services to China,” April 17, 2018, https://space.fmi.fi/2018/04/17/fmi-provides-satellite-services-to-china/.

- “Defence Ministry Blocked Chinese Plans for Research Airbase in Lapland,” Yle News, April 3, 2021, https://yle.fi/a/3-11820411.

- Matti Puranen and Sanna Kopra, “Finland and the Demise of China’s Polar Silk Road,” The Jamestown Foundation, December 30, 2022, https://jamestown.org/program/finland-and-the-demise-of-chinas-polar-silk-road/.

- Jonathan Barrett and Johan Ahlander, “Exclusive: Swedish Space Company Halts New Business Helping China Operate Satellites,” Reuters, December 21, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/exclusive-swedish-space-company-halts-new-business-helping-china-operate-satell-idUSKCN26C1ZS/.

- “Big Science Infrastructure,” Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, http://english.aircas.cn/research2020/bsi/202302/t20230213_327036.html.

- “Swedish Security Experts: We’re Too Naive about China,” SVT Nyheter, January 15, 2019, https://www.svt.se/nyheter/utrikes/swedish-security-experts-we-re-too-naive-about-china.

- “China Iceland Arctic Research Observatory,” Interact International Network for Terrestrial Research and Monitoring in the Arctic, https://eu-interact.org/field-sites/karholl-research-station/.

- Kristín Ingvarsdóttir and Guðbjörg Ríkey Th. Hauksdóttir, “Science diplomacy for stronger bilateral relations? The role of Arctic science in Iceland’s relations with Japan and China,” The Polar Journal, Vol. 14 (2024): pp. 314-332, https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2024.2342114.

- Ibid.

- Andreas Raspotnik, “’Solar-Terrestrial’ Interaction Between Iceland and China,” High North News, April 4, 2016, https://www.highnorthnews.com/nb/solar-terrestrial-interaction-between-iceland-and-china.

- Ingvarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir, “Science diplomacy for stronger bilateral relations?.”

- Michael Rubin, “Iceland: China’s Trojan Horse in Europe,” American Enterprise Institute, November 22, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20241204050433/https://www.aei.org/op-eds/iceland-chinas-trojan-horse-in-europe/.

- Letter from U.S. House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party.

- Kjartan Kjartansson, “Njósnir Kínverja á Íslandi viðkvæmt mál sem nauðsynlegt sé að ræða,” Vísir, March 27, 2025, https://www.visir.is/g/20252706806d/njosnir-kin-verja-a-is-landi-vid-kvaemt-mal-sem-naud-syn-legt-se-ad-raeda?fbclid=IwY2xjawJTfQJleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHZTBkqDyZ0B3fEjeUVfBiGMkkD609hHD7KhpPkFmXDg1q-pGfKQPDmsjzQ_aem_dy_C4Wh1F3osP0kr7XepiA.

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China to Iceland, “Groundless Accusations Are Not Conducive to China-Iceland Friendly Cooperation,” March 28, 2025, http://is.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zbgx/202503/t20250328_11583907.htm.

- “China Global Investment Tracker.”

- “Teck Shares Slump with China’s Sell,” Elk Valley Coal News, https://elkvalleycoal.com/teck-shares-slump-chinas-sell/.

- “Chinese Companies Agree to Develop LNG in Alaska as Trump Visits,” Reuters, November 9, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/chinese-companies-agree-to-develop-lng-in-alaska-as-trump-visits-idUSKBN1D90OA/.

- Arne O. Holm, “Arctic Council Tensions Run High: Verbal Thunderstorm from Mike Pompeo,” High North News, May 7, 2019, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/verbal-thunderstorm-mike-pompeo.

- Office of the White House, “National Strategy for the Arctic Region,” October 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Strategy-for-the-Arctic-Region.pdf.

- Marc Lanteigne and Mingming Shi, “China Steps Up Its Mining Interests in Greenland,” The Diplomat, February 12, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/china-steps-up-its-mining-interests-in-greenland/.

- Greenland Ministry of Mineral Resources and Justice, “Stop for olieefterforskning i Grønland,” July 15, 2021, https://naalakkersuisut.gl/Nyheder/2021/07/1507_oliestop?sc_lang=da.

- “China Withdraws Bid for Greenland Airport Projects,” Reuters, June 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/business/china-withdraws-bid-for-greenland-airport-projects-sermitsiaq-newspaper-idUSKCN1T5190/.

- “Greenland Strips Chinese Mining Firm of Licence to Iron Ore Deposit,” Reuters, November 22, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/greenland-strips-chinese-mining-firm-licence-iron-ore-deposit-2021-11-22/.

- Erik Matzen, “Denmark Spurned Chinese Offer for Greenland Base Over Security,” Reuters, April 6, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/denmark-spurned-chinese-offer-for-greenland-base-over-security-sources-idUSKBN1782E1/.

- Michael Paul, “Greenland’s Project Independence,” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, German Institute for International Affairs, January 10, 2021, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2021C10_GreenlandIndependence.pdf.

- Hans van Leeuwen, “How an Aussie Zinc Miner Switched Horses from China to the US,” Financial Review, December 8, 2021, https://www.afr.com/companies/mining/how-an-aussie-zinc-miner-switched-horses-from-china-to-the-us-20211208-p59fpt.

- Martin Breum, “A Year into Biden’s Presidency, U.S. Military Plans for Greenland Remain Unclear,” Arctic Today, January 19, 2022, https://www.arctictoday.com/a-year-into-bidens-presidency-u-s-military-plans-for-greenland-remain-unclear/.

- Esmarie Iannucci, “Ironbark Taps Potential Partner for Citronen,” Mining Weekly, May 23, 2022, https://www.miningweekly.com/article/ironbark-taps-potential-partner-for-citronen-2022-05-23.

- Michael Allan McCrae, “Zinc Project in Greenland Receives Chinese Backing,” Mining.com, August 11, 2017, https://www.mining.com/zinc-project-greenland-receives-chinese-backing/.

- Walter Turnowsky, “Kinesisk selskab kan ikke overtage uran-projekt,” Sermitsiaq, June 14, 2017, https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/erhverv/kinesisk-selskab-kan-ikke-overtage-uran-projekt/595027.

- Cecilia Jamasmie, “Greenland Bans Uranium Mining, Blocking Vast Rare Earths Project,” Mining.com, November 10, 2021, https://www.mining.com/greenland-bans-uranium-mining-blocking-vast-rare-earths-project/.

- Yang Jiang, “Chinese Investments in Greenland,” Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Report Vol. 2021 No. 05, https://research.diis.dk/files/4834625/Chinese_investments_in_Greenland_DIIS_Report_2021_05.pdf.

- “Memorandum of Understanding Between the State Oceanic Administration of the People’s Republic of China and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and the Church of Greenland on Scientific Cooperation,” https://www.nis.gl/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/MoU-IKIIN-og-State-Oceanic-Administration-China.pdf.

- Cui Xueqin, “北师大在格陵兰启动北极第二个卫星地面站建设,” ScienceNet.cn, June 4, 2017, https://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2017/6/378159.shtm.

- “Greenland: China Discreetly Launches Satellite Ground Station Project,” Jichanghulu, December 14, 2017, https://jichanglulu.wordpress.com/2017/12/14/greenland-satellite/.

- Walter Strong, “Ottawa Blocks Chinese Takeover of Nunavut Gold Mine Project after National Security Review,” CBC, December 22, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/canada-china-tmac-1.5851305.

- “Nunavik Nickel Mine,” MDO Data Online Inc., https://miningdataonline.com/property/1603/Nunavik-Nickel-Mine.aspx.

- Jane George, “Nunavik Mine Owes $72 Million to Creditors; Chinese Owners Turn Project Over to Toronto Bank,” Nunatsiaq News, August 14, 2013, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/65674nunavik_mine_owes_72_million_to_creditors_chinese_owners_turn_project_/.

- “Project Overview,” Selwyn Chihong, https://selwynchihong.com/project/.

- “Development Projects,” MMG Australia Limited, https://www.mmg.com/our-business/development-projects/.

- Senate of Canada, “The Grays Bay Road and Port Project,” October 1, 2018, https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/421/ARCT/Briefs/2018-10-01_NRC_e.pdf.

- Jackie Hong, “Receivership Ending at Yukon’s Abandoned Wolverine Mine, Gov’t Now Looks to Closure, Remediation,” CBC News, February 15, 2024, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/receivership-wolverine-mine-pwc-discharged-1.7116781.

- “Judge Rules in Favour of Yukon Government Seeking Money for Mine Cleanup,” CBC News, June 4, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/yukon-zinc-wolverine-mine-yukon-costs-ruling-1.5597619.

“Lac Otelnuk Iron Projet, Quebec,” Mining Technology, August 15, 2016, https://www.mining-technology.com/projects/lac-otelnuk-iron-project-quebec/.