Trade, Aid, and Influence

From the Preface to China into Africa:

Africa attracted China as early as the T’ang dynasty (A.D. 618–907); ninth century reports of the meat-eating, ivory-exporting people of Po-pa-li in the “southwestern sea” may refer to the inhabitants of what is now modern Kenya or Tanzania. By the eleventh or twelfth centuries, the city-state dwellers from Pate to Kilwa along the eastern African coast appeared to have been shipping elephant tusks, rhinoceros horn, tortoise shell, aromatic woods, incense, and myrrh directly or indirectly to southern China. During the Sung dynasty (A.D. 1127–1279), Chinese shipping was common throughout the western reaches of the Indian Ocean. Chinese objects from this period of all kinds, including specie, have been found from today’s Somalia to Mozambique. Chinese references to k’un lun—slaves as “black as ink”—are also common from Sung times. But it is from the fifteenth century that we can date China’s first certain direct involvement with Africa. Between 1417 and 1431, the Ming emperors dispatched three large expeditions to eastern Africa to collect walking proof of the celestial approval of their virtuous and harmonious reigns. Only Africa could supply a confirmation of these blessings; the arrival of unicorns from distant lands would supply the propitious signs of heaven’s mandate, and only in Africa could unicorns—giraffe—be found. Hence, from Kenya or Tanzania a number of giraffe (and other animals) were strapped to the pitching decks of Chinese junks and transported across the sea to the imperial palace in distant Beijing.

China and Africa have enriched each other intellectually, culturally, and commercially ever since. But direct contact and interactive influence have been episodic. During the middle years of the twentieth century, Maoist China funded and educated sub-Saharan African anticolonial liberation movements and leaders, some of which and some of whom later emerged victorious in their national struggles for freedom; others lost out to Soviet-backed movements. China assisted the new nations of sub-Saharan Africa during the remainder of the twentieth century, especially by providing military hardware and training, but also by providing Chinese labor and capital to construct major railways and roads.

Africa and China are now immersed in their third era of heavy engagement. This one is much more transformative than the earlier iterations. Indeed, as the contributed chapters in this book make very evident, China’s current thrust into sub-Saharan Africa promises to do more for economic growth and poverty alleviation there than anything attempted by Western colonialism or the massive initiatives of the international lending agencies and other donors. China’s very rapaciousness—its seeming insatiable demand for liquid forms of energy, and for the raw materials that feed its widening industrial maw—responds to sub-Saharan Africa’s relatively abundant supplies of unprocessed metals, diamonds, and gold. China also offers a ready market for Africa’s timber, cotton, sugar, and other agricultural crops, and may also purchase light manufactures. This new symbiosis between Africa and China could—as this book demonstrates—be the making of Africa, the poorest and most troubled continent.

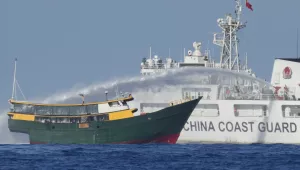

There are major cautions, too, which most of the chapters in this book spell out. China is no altruist. It prides itself on not meddling and on merely desiring Africa’s resources. Thus it professes to care little about how individual African nations are being ruled; nor does it seek to change or improve the societies in which it is becoming a major, if not the dominant, commercial influence. China is extractive and exploitive, while simultaneously wanting friends and seeking to remove any remaining African ties to Taiwan. China also does not yet understand that, as salutary as competition might be for Africa’s continuing maturation, importing Chinese labor to complete Chinese-organized infrastructural and mining projects inhibits skill transfers and reduces indigenous employment growth. Doing so also breeds resentment, as does the undercutting of local merchants and industrialists by the supply of cheaper Chinese goods or sharper Chinese entrepreneurial instincts. Africans, and Westerners certainly, further complain about China’s disdain for human rights and mayhem in Africa. The fact that China may have been and may still be morally complicit in the Sudan’s massacring of Darfuri civilians or the repression of Equatorial Guineans and Zimbabweans, through the supply of weapons of war to the relevant militaries and through the refusal to employ its evident economic leverage appropriately on the side of peace, weighs heavily in the balance.

China is opportunistic. The contributions to this book assess the positive and negative results of its latest move into Africa, and look at each of the salient issues in turn. Fortunately, in creating a final, mixed conclusion, the contributors do so by weighing the available evidence dispassionately and from a variety of national perspectives. This is as much an African as a Chinese analysis, with European and American inputs as well.

Rotberg, Robert. “China into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence.” Brookings Institution Press and World Peace Foundation, October 2008