As I have been researching "smart city" harms and prevention tactics, I have reviewed current surveillance technology laws with an eye for how they are being constructed, applied, and subverted. This post summarizes their status to date, what they are missing, and some initial thoughts on where legal protections might go next.

Why Surveillance Technology Laws

Many legal scholars have argued regulation is needed to protect people from harmful government surveillance because Fourth Amendment judicial scrutiny is too limited in scope and slow to be reviewed. Unlike Fourth Amendment protections, regulation could categorically limit certain types of surveillance (rather than relying on a reasonable search analysis), and it could also address private-sector surveillance sources, which are often excluded from Fourth Amendment scrutiny via the third-party doctrine. Further, proactive regulation could prevent surveillance harms before they occur, while judicial review can only occur after the damage is done. Lastly, regulation could change reflexively with community values beyond the imagination of the Constitution's drafters.

This post will only cover the sixteen local "surveillance technology" laws (cited and linked below) and will not cover related facial recognition technology laws, biometric laws, and consumer privacy laws that are also trending. Four of the jurisdictions that have passed surveillance technology laws (Berkley, Cambridge, San Francisco, and Somerville) have also banned facial recognition technology to some extent.

Missing Sources

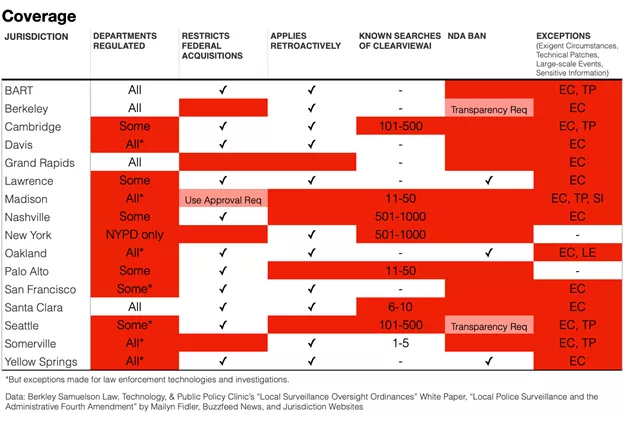

Surveillance technology laws currently have a broad range of applicability when it comes to who, what, and even when these oversight provisions kick in on the frontend, as well as exceptions and loopholes on the backend. Is anything included? Let us dig in.

What is regulated?

While a goal of surveillance technology regulation is to limit harmful surveillance before it occurs, it is challenging to craft a definition of "surveillance technology" that is broad enough to anticipate all potential types of new technology and narrow enough to be implementable. Many of these ordinances begin by defining "surveillance technology" as:

"any electronic surveillance device, hardware, or software that is capable of collecting, capturing, recording, retaining, processing, intercepting, analyzing, monitoring, or sharing audio, visual, digital, location, thermal, biometric, or similar information specifically associated with, or capable of being associated with, any Identifiable Individual or group..."

They then go on to include a detailed list of included and excluded technologies. While the above definition is flexible enough to apply to many new technologies and targets data re-identification, many jurisdictions exclude "cameras attached to government property," "medical equipment," and "parking citation devices," all of which could be deployed in ways that constitute the kind of surveillance these laws are supposed to prevent. For example, imagine powerful streetlight cameras or facial recognition technology kiosks being excluded from oversight as "cameras on government property" or "medical equipment." Many of the definitions and exclusions were long, and some used circular logic, making these laws challenging to implement. Others included specific types of surveillance technology (ISMI catchers) or company brand names (Shotspooter) that may not be relevant in the future. Definitions are important! San Francisco had to amend their facial recognition technology definition after realizing it included iPhones used by government employees.

Given the complexity of capturing all potential surveillance tools as technology continues to advance and proliferate, legislators may want to consider inclusive and principles-based definitions and allow for policy mechanisms that can be updated iteratively. For example, jurisdictions may lead with technology definitions that include "technology that collects or manages information that can re-identify a person or group" or "all novel technologies" and then maintain specific lists of prohibited technologies (e.g., "facial recognition technology") by name as public policy documents. Jurisdictions may also want to regulate certain types of data collection (as biometrics laws have done) or specific uses (as is the case with the U.S. Census data, which cannot be shared with law enforcement) to achieve their overall objectives. Lastly, to ensure all of these types of tech (or data or uses) are being captured, legislators may want to require a third-party audit of government systems and practices.

Who is regulated?

In addition to definitional challenges, surveillance technology laws vary broadly in who they oversee. Only four jurisdictions' surveillance technology laws applied to all departments without exceptions for certain law enforcement technologies and investigations. Also, four jurisdictions failed to include federal acquisitions in their oversight scheme despite ample evidence that some of local government's most sophisticated surveillance tools come from federal sources. Moreover, even if surveillance technology is prohibited in your jurisdiction, it is common practice to get similar data from neighboring and overlapping jurisdictions where it is not prohibited.

In addition to gaps in department and jurisdiction coverage, there has been fantastic investigative reporting on the rampant government use of data collected by private data brokers to track cars, cell phone location, faces, home security cameras, and utilities. Private-sector data brokers sometimes provide this data for free to governments bypassing procurement rules and political review and often require nondisclosure agreements (NDAs), bypassing public and judicial scrutiny. Only three jurisdictions ban the use of NDAs as part of their surveillance technology law. Advocates at the EFF call for banning government use and strict limits to private use of facial recognition technology given their risk/utility levels. While this distinction may make sense theoretically, today, private use is barely limited, and the entanglement of government and private use is severe. Given the use of private tools by government employees to "get the job done" (such as email and messaging apps) and the growing amateur use of facial recognition technology to identify people, I suspect a bright-line distinction between government and non-government regulation will be difficult to implement on the ground.

To ensure these regulations are effective, legislators may want to consider national, state, and regional opportunities, as well as private sector prohibitions (like Portland and New York City have done for facial recognition technology and as proposed by Senator Wyden this week with The Fourth Amendment is Not For Sale Act). Advocates may want to study obstacles to surveillance technology law passage and lobbying trends to strategically surmount those loci of power. Audits like investigative journalists have been doing above can help capture all government use of surveillance data, whether it originated from another government or a private source.

When is it regulated?

Surveillance technology laws vary in when they apply. Five jurisdictions' surveillance technology laws do not apply retroactively, and fourteen have exceptions for incidents as they arise, such as exigent circumstances, technical patches, and large-scale events. While retroactive oversight could be costly and disruptive to active programming, jurisdictions that aim to regulate harmful surveillance may want to reconsider automatically grandfathering in practices already in place, which may be very dangerous. Similarly, while space for emergencies is desirable, much of harmful historical surveillance has been categorized under such terms.

To ensure surveillance technology laws oversee all harmful surveillance, legislators may consider nuanced oversight schemes that treat retrospective or emergency technology use differently but do not remove it from oversight. For example, retroactive review can be prioritized by public input. For emergency applications, additional enforcement penalties could be levied if inappropriately used to avoid oversight, and other requirements could be imposed, such as no data retention.

Missing Actualization

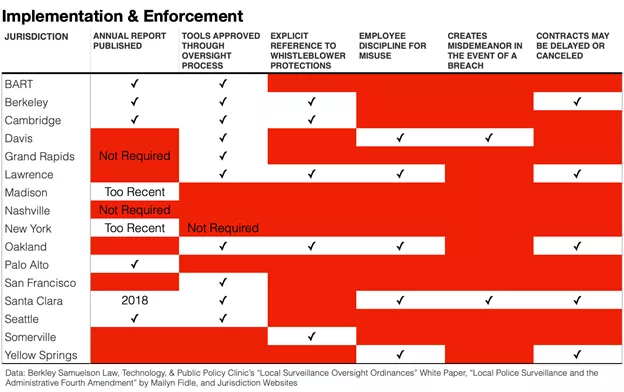

Surveillance technology laws vary in their oversight requirements, implementation status, and teeth. While many of the reporting requirements are similar in kind, several jurisdictions have not completed these reports, and they vary in quality. The enforcement mechanisms also vary across jurisdictions.

What does implementation look like?

While fifteen jurisdictions require an annual report, I could only find 2020 annual reports for five. Some jurisdictions did not have an annual report online but did have some impact reports submitted to the city council for review online. BART, Berkley, Oakland, Santa Clara, San Francisco, and Seattle all had Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs) submitted (and it looks like approved) through their oversight process. While this technology could be scoped to uses the community is comfortable with, its approval is concerning considering its known discriminatory effects. On the other extreme, Cambridge's surveillance technology reports included their RMV website and Tweetdeck. While these certainly could be used for harmful surveillance, one wonders if other government website or social media policies may be able to address these concerns rather than putting everything through surveillance technology review. Also, it is easy to imagine personal use of Tweetdeck subverting any government use restrictions. Other annual reports like Palo Alto's barely had any information, and many of the individual impact and use reports lacked evidence or rigor, for example, stating the cost-effectiveness of a tool without any comparative analysis (BART) or relying solely on a lack of complaints to determine impacts on equity (Seattle). Seattle had the most comprehensive reports online, including quarterly review and also what was considered a non-surveillance technology, and they were the easiest to find and navigate. For the jurisdictions without an annual report posted online, we can look to EFF's Atlas of Surveillance to get a sense of some of the tools they are currently using, see: Davis, CA (ALPRs, BWCs), Grand Rapids, WI (ALPRs, cameras, Ring), Lawrence, MA (BWCs), Nashville, TN (ALPRs, drones, face recognition, fusion center, predictive policing), Oakland, CA (ALPRs, BWCs, cell-site simulator, drones, gunshot detection), San Francisco, CA (ALPRs, BWCs, cell-site simulator, drones, fusion center, gunshot detection). If these are the tools being using in jurisdictions with surveillance technology oversight laws, what takes place in jurisdictions without oversight? Somerville and Yellow Springs currently don't have reports online nor any surveillance technology listed on Atlas of Surveillance.

To ensure reporting gets completed and is actively reported out to the public, legislators may want to consider baking surveillance technology reporting into ongoing processes such as strategic planning or budgeting in addition to specific surveillance technology reports and be sure to include these items if approved, are flagged in transparent procurement processes. Legislators may want to consider if these reports are applying enough rigor and are accessible enough to inform public engagement and adjust as needed.

What does enforcement look like?

In addition to varying levels of implementation, jurisdictions have a range of enforcement mechanisms. Some jurisdictions highlight local whistleblower protectors in their ordinance. Some include options to discipline or criminally charge employees who fail to follow the law. And some allow for the cancelation of non-compliant contracts. I could not find readily available evidence of how often, if at all, these enforcement mechanisms have been used to date. It would be fascinating to see what enforcement has occurred in jurisdictions like Somerville that have not published an annual report on time and where their City Council is currently following up.

To encourage employee disclosure, legislators may want to highlight whistleblower protections and consider a campaign for reporting known breaches. In addition to requiring these enforcement mechanisms, legislators may want to transparently disclose which departments and employees have been disciplined.

Missing the Point?

Surveillance technology laws might be missing more than coverage and implementation. They might be missing the very thing they are after: protecting people from harmful surveillance.

Do these laws stop discrimination?

Disproportionate impact to black and brown (and other historically discriminated against communities) is a well-documented surveillance harm. Bruce Schneier highlights the distinct need to regulate the discriminatory aspects of surveillance technologies in his January 2020 op-ed entitled We're Banning Facial Recognition. We're Missing the Point:

"In all cases, modern mass surveillance has three broad components: identification, correlation, and discrimination...Regulating this system means addressing all three steps of the process. A ban on facial recognition won't make any difference if, in response, surveillance systems switch to identifying people by smartphone MAC addresses. The problem is that we are being identified without our knowledge or consent, and society needs rules about when that is permissible… [and] we need better rules about when and how it is permissible for companies to discriminate. Discrimination based on protected characteristics like race and gender is already illegal, but those rules are ineffectual against surveillance and control technologies. When people can be identified and their data correlated at a speed and scale previously unseen, we need new rules."

ACLU's Community Control Over Police Surveillance (COPS) model legislation, which has inspired many of these surveillance technology laws, aims to prevent discrimination by including a disparate impact analysis requirement. None of the sixteen jurisdictions have used this portion of their model language entirely. Three jurisdictions (Lawrence, Seattle, and Yellow Springs) have the strongest language related to disparate impact analysis, with Seattle being the only jurisdiction that requires Equity Impact Assessments. Six jurisdictions (BART, Berkley, Cambridge, NYPD, Palo Alto, San Francisco) mention disparate/disproportional impact in their reporting sections. Four broadly mention civil rights (Oakland, Nashville, Santa Clara, Somerville). And three don't mention discrimination at all (Davis, Grand Rapids, Madison). Given the light touch of disparate impact analysis in the published reports online (see above), advocates may consider providing more implementation tools for such impact analyses or consider if the prospective analysis is a tool jurisdiction are capable of or willing to do.

Advocates who want to prevent these discriminatory harms have criticized surveillance technology oversight regulations stating that they reinforce the use of these technologies by formalizing processes around their existence rather than prohibiting their use full stop. This critique is inextricably linked to broader conversations about racism, inequality, and harmful policing practices. STOP LAPD Spying has explicitly called for an end to the CCOPs campaign and for abolishing surveillance technologies that are discriminatory. Tawana Petty, the National Organizing Director for Data 4 Black Lives, has similarly called for an end to facial recognition technology because of its detrimental effects on the black community. The Action Center on Race & the Economy has published a set of recommendations for 21st Century Policing that couple the broader national call to defund the police and invest in community safety with explicit calls to end surveillance data collection and end all funding of surveillance technology.

Given the evidence that these technologies have discriminatory effects and limited evidence that prospective disparate impact analyses are effective, legislators may consider heading these calls to prohibit surveillance technology that exacerbates discrimination (as cities like Oakland and New Orleans are beginning to do with predictive policing bans) and seek policies that reduce surveillance instead of overseeing it.

Is surveillance technology necessary?

Another critique of surveillance technology has been policymakers' attitude that such surveillance is inevitable or necessary because of public policy aims of safety and welfare. In addition to the above discrimination question that asks whose safety is being protected, are communities gaining an amount of safety that warrants this much surveillance? In 2013, EFF developed a set of International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance that challenged how much surveillance was necessary given the risks. Their principles call for analyses missing from current surveillance technology laws, including reviewing if surveillance is necessary, adequate, and proportional [to risks], and they also call for a user notification requirement. With headlines such as Despite Scanning Millions of Faces, Feds Caught Zero Imposters at Airports Last Year, is surveillance meeting these principle thresholds today?

Given the known risks, potential risks, and public concerns related to surveillance technologies, legislators may consider flipping oversight of these tools on their heads and ask for agencies to prove why they are necessary in the first place. And demand more rigor and oversight on why these tools are better choices than another programming.

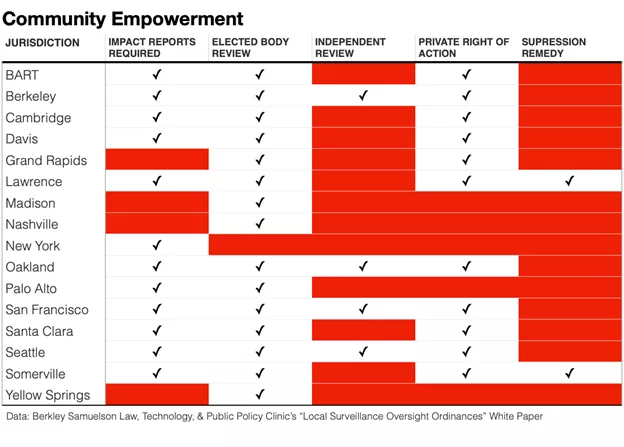

Do these laws empower communities?

In addition to varying impact analyses, surveillance technology laws vary widely in how involved community members are in oversight decision-making and what remedies are available to them if harmful searches occur. All jurisdictions provide an elected body to review surveillance technology except for the NYPD (because of NYC City Council rules), but only four include an independent review (Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, Seattle). While ten jurisdictions provide a private right of action when the jurisdiction fails to provide corrective actions, they vary in the type of relief they provide. Some jurisdictions limit relief to injunctive relief (e.g., Seattle). Some cap monetary damages (e.g., Berkley caps out at $15,000) or prohibit the inclusion of attorney fees. And some provide fully for actual damages, including attorney fees (Oakland). Only two jurisdictions provide a suppression remedy if the government obtains evidence against you per an invasive search not permissible by the surveillance technology law.

To ensure community norms are thoroughly represented in a jurisdiction's use of surveillance technology, legislators may consider proactive design justice principle-infused policymaking well in advance of any decisions to include technology or data collection. To ensure communities are thoroughly protected from surveillance technology harms, legislators may consider providing for suppression remedies in addition to private rights of action with comprehensive types of relief.

What’s Next?

Given the current state of surveillance technology laws, what's next? I think we can expect to see privacy-related laws of all flavors to continue to trend and hopefully will see more analysis on what approaches are most effective. Similarly, we can expect to see Fourth Amendment scholars and litigators continue to fight for the expansion of Fourth Amendment protections to new digital applications (such as ALPRs, scooter data, or smart city sensors). How the Supreme Court responds to new Fourth Amendment cases may be affected by this advocacy as well as public sentiment writ large. In addition to these incremental approaches, there could be national regulation or new ways of thinking about regulating privacy contextually, as Helen Nissenbaum has suggested. If privacy concerns continue to uptick without proportional regulation, we may also see new tools and techniques to obfuscate surveillance technologies become more prevalent.

What do you think? What did I miss? Get in touch: rebeccawilliams@hks.harvard.edu

Further Reading

- To keep up with new privacy legislation broadly, follow the Whose Streets? Our Streets! (Tech Edition) newsletter and check out further reading below.

- Berkeley Law’s Samuelson Law, Technology, and Policy Clinic's ”Local Surveillance Oversight Ordinances” white paper

- Mailyn Filder’s “Local Police Surveillance and the Administrative Fourth Amendment” law review article and Lawfare reporting

This post covers the 16 U.S. local “surveillance laws'' all scoped to govern the use of “surveillance technologies'' including Berkeley, Cal., Mun. Code § 2.99 (2018); Cambridge, Mass., Mun. Code §2.128 (2018); Davis, Cal., Mun. Code §26.07 (2018); Grand Rapids, Mich., Admin. Pol’y§15-03(2015); Lawrence, Mass., Mun. Code §9.25 (2018); Madison, Wis., Mun. Code §23.63 (2020); Nashville, Tenn., Metro. Code §13.08.080 (2017); N.Y.C., N.Y., Admin. Code §14-188 (2020); Oakland, Cal., Mun. Code §9.64 (2021); Palo Alto, Cal., Admin. Code §§2.30.620–2.30.690(2018); S.F., Cal., Admin. Code §19B (2019); S.F. Bay Area Rapid Transit Dist., Cal., Code§17(2018); Santa Clara Cnty., Cal., Mun. Code §A40 (2016); Seattle, Wash., Mun. Code §14.18 (2017); Somerville, Mass., Mun. Code §§10-61–10-69(2019); Yellow Springs, Ohio, Mun. Code §607 (2018).

Williams, Rebecca . “Everything Local Surveillance Laws Are Missing In One Post .” April 26, 2021