Panelists:

- Kenneth Katzman

- David Kay

- John Lauder

- Michael Singh

- William Tobey

Moderated by the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control

Introduction

Since the beginning of the year, the P5+1 group of countries have held several rounds of talks with Iran, the objective being to find a comprehensive solution to the dispute over that country’s nuclear program; the latest round was held this week in Vienna. The talks are expected to run through July and may extend for a further six months. In the meantime, an interim accord is in effect, under which Iran has restricted its nuclear expansion in exchange for limited relief from sanctions.

Last December, President Barack Obama cautiously predicted that there was a less than even chance the talks would succeed in achieving a final agreement. Administration officials have sounded more optimistic recently. There has even been speculation in the media that the two sides could begin moving toward a final deal this month, and conclude a deal by the July deadline. Yet, after several rounds of negotiation, the two sides are still far apart, in particular on the extent and nature of Iran’s continuing uranium enrichment work.

What would be the consequences if, in the absence of a comprehensive solution, the interim deal became, de facto, permanent? Would this solution satisfy the United States, its allies, or Iran? Does the interim deal have gaps that would be fatal to any long-term arrangement? What are the consequences if no deal is reached? And, are such consequences better or worse than those resulting from an extension of the interim deal, or from a deal that fails to meet minimum acceptable standards?

These questions were addressed at a private roundtable discussion hosted by the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control on April 25, 2014. The participants were Kenneth Katzman, Specialist in Middle East Affairs at the Congressional Research Service, David Kay, a Senior Fellow at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, John Lauder, who spent over 30 years working on nonproliferation and arms control at the Central Intelligence Agency, Michael Singh, Managing Director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, and William Tobey, Senior Fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

There was broad consensus among the participants that there is substantial momentum now toward moving beyond the interim deal to a more comprehensive agreement. The participants also judged that the interim deal should not become permanent because it does not contain several key elements. These include a full explanation of Iran’s past nuclear work, adequate means to verify its ongoing nuclear work, a sufficient curb on Iran’s nuclear “breakout” potential, and an arrangement for controlling Iran’s future nuclear procurement. The participants also concluded that there will be important costs to striking a deal with Iran, and therefore that certain critical elements – such as those listed above – must be included for the deal to be considered adequate, and worth those costs. Following is the moderators’ summary of the discussion. The findings below and the summary above are a composite of the panelists’ individual views. No finding should be attributed to any single panelist, or be seen as a statement of policy of any government.

The interim nuclear accord with Iran is not likely to evolve into a permanent deal, even if the present talks should fail.

The interim accord was a “standstill” agreement, never meant to be final. It omits many elements a final deal should include. Among these omitted elements are: an adequate ability to inspect Iran’s nuclear program, an adequate knowledge of Iran’s suspected attempt to develop nuclear weaponry, an adequate means of preventing secret nuclear-related imports by Iran, and an adequate amount of time to detect and organize a response if Iran is discovered to be “breaking out,” or making a dash to nuclear weapons. Iran’s current “breakout” window for one weapon is generally estimated to be on the order of three months, but there is uncertainty about the full extent of Iran’s nuclear weapons program. The United States reportedly is seeking to extend that window to twelve months.

Congress would not accept the interim accord as permanent. Most members are unhappy about the current pause in sanctions and would not wait beyond the built-in twelve month expiry date of the accord to enact new ones. Nor would U.S. allies in the Middle East accept the interim accord as final because it does not require Iran to answer questions about past nuclear work with military applications.

Finally, Iran is unlikely to accept the status quo because the interim accord requires Iran to freeze work on its heavy water reactor, cease expanding its centrifuge plants, and end production of higher enriched uranium. Moreover, Iran would be uncertain of gaining substantial sanctions relief under the status quo.

The interim accord does not reveal Iran’s true nuclear intention.

If Iran should agree to a final deal that is adequate, it would be at least some evidence that Iran had made an important decision: to join the international community instead of bucking it, and to get off the path toward becoming a nuclear weapon state (virtual or actual), as least for now. The most important proof of such a decision will be Iran’s willingness to explain nuclear research that has “possible military dimensions” – work that has no place in a civilian program, but is essential to nuclear weapons. If Iran fails to explain this work, it will show that Iran has not made such a strategic decision. The same will be true of missiles. If Iran does not intend to develop a nuclear warhead, Iran will not need the long-range missiles it is currently developing. The inaccuracy of these missiles makes them ineffective for delivering conventional warheads. Iran would accept restraint on its missiles if its intention is peaceful.

However, even Iran’s acceptance of an adequate deal will not be conclusive evidence that Iran has made a fundamental strategic decision to give up nuclear weapons. Iran could violate the agreement, as Iran has violated its pledges under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. Conclusive evidence of Iran’s nuclear intention would only come through a broader understanding that addresses Iran’s overall behavior. Embedding a nuclear agreement in such a broader understanding may also make it less likely that Iran will violate the agreement.

To be adequate, a final deal must include the following: robust verification of nuclear material, equipment and research; a full explanation of nuclear weapon-related work; an effective mechanism for controlling all nuclear-related procurement; and an increase in the time it would take Iran to “breakout.”

Verification: Critical parts of Iran’s nuclear program are still unknown. A final deal must allow access to sites, persons, and records sufficient to insure that Iran’s program is fully understood. That is, to determine that Iran has no “bomb in the basement,” nor the ability to produce one, and that Iran no longer conducts secret activities or has secret sites. Such transparency does not now exist. Iran should be required to supply a comprehensive accounting of its past and present nuclear work. Countries could examine the accounting for internal inconsistencies, and compare it to national intelligence information. Such analysis could be used to support inspections. A forum of some sort would be necessary to discuss inconsistencies that arise, as well as ongoing compliance. This is an arms control monitoring model that has worked in the past.

Weapon development: The United States and other countries have compiled evidence linking Iran to nuclear weapon research. Iran has explored technologies uniquely suited to building and testing fission bombs, including seeking to develop missiles capable of carrying a nuclear payload. Iran has refused requests by the International Atomic Energy Agency to explain this research. A final deal must require a full explanation. Without it, Iran’s intention will remain suspect. In addition, the explanation is needed to establish how close Iran may be to the ability actually to field a nuclear weapon, and to reveal whether Iran may still have secret sites. For all these reasons, the explanation of its suspicious research should be a requirement of a final deal.

Procurement: Iran imported materials relevant to its nuclear enterprise illicitly for many years, and continues to do so. A final deal must prevent such imports. The best way to accomplish this is to set up an agreed channel for nuclear imports that would be exclusive. No import outside the channel would be permitted, and such a channel would include a mechanism for regulating what Iran is allowed to buy. The IAEA would be provided with a list of licitly procured equipment, and supplier countries could conduct end-use checks. This type of arrangement will be essential if a final deal relaxes the rules now barring Iran from nuclear-related procurement. Without such a mechanism, there would be a great risk that Iran could divert newly-permitted imports to secret sites. Iran can be expected to seek nuclear assistance from many countries; there must be a way to determine which imports are legitimately needed for a peaceful nuclear enterprise and which are not. No such mechanism exists now.

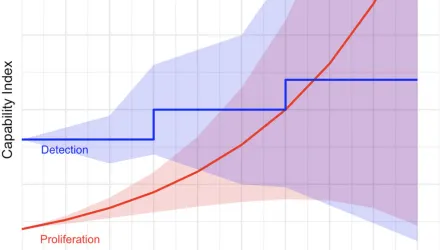

Breakout time: Iran is estimated to be able to make the fuel for a nuclear weapon in two to three months. The estimate assumes that Iran would feed its stockpile of enriched uranium gas through the roughly 9,000 gas centrifuges it is operating. In addition, Iran is building a heavy water reactor that could produce enough plutonium for approximately two bombs per year. A final deal cannot leave this capability in place. The deal must either eliminate uranium enrichment and the heavy water reactor, or eliminate the possibility that Iran could use either to fuel a bomb quickly. If the reactor remains, its plutonium production should be reduced to a token level, with any plutonium removed from the country. If enrichment is not eliminated, it should be reduced to a token level, with any enriched material being removed from the country. Research and development work on more efficient centrifuges must also be constrained. Such machines are several times more powerful than those Iran is currently operating, and would reduce Iran’s breakout time if deployed in larger numbers. Their wider use in Iran also increases the risk posed by covert sites; advanced centrifuges would increase Iran’s capability to operate a small enrichment plant secretly, using fewer centrifuges, and thereby decrease the chance of detection.

There will be a number of costs to striking a final deal. Therefore, it is crucial to get a final deal that is adequate. The costs are damage to nonproliferation standards; political legitimization for Iran; and diminished attention to the Iranian threat by governments.

Undermining U.S. nonproliferation standards: If a final deal allows Iran to retain uranium enrichment and a heavy water reactor, which now seems likely, U.S. allies will demand the right to have the same. The United States has blocked uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing in both South Korea and Taiwan. An agreement not to pursue these activities represents a “gold standard” in nuclear cooperation agreements with the United States. It has been accepted by U.S. allies like the United Arab Emirates. But once the United States approves sensitive nuclear activity in Iran, it will be difficult to convince America’s allies to forego it.

Political legitimization: A final deal will inevitably bolster the regime in Iran. U.S. policy in Syria shows the effect of such agreements. In Syria, the United States reduced its effort to get rid of the Assad regime – the primary strategic goal – to clear the way for a deal orchestrated by Russia to eliminate Syria’s chemical weapons, which was a secondary goal. The result was to cement Assad’s position, prolong the war, and increase civilian casualties.

Loss of interest by governments: After a final deal, which political leaders will present as “solving” Iran’s nuclear problem, governments will shift their attention to other matters. Nevertheless, it will still be necessary to strictly monitor Iran’s compliance. In that sense, no deal will really be “final.” Rather, it will impose imperfect constraints on Iran and will be the equivalent of containment. For nearly three decades, Iran broke its word to inspectors, conducted illicit research, and built secret sites. It may do so again. Yet, political leaders will be loath to have Iran back on their agenda. They may contest, or even ignore, any damning intelligence finding. Such findings may also become increasingly rare, as the government resources focused on Iran are directed elsewhere. Nor is it likely that there will be an effective response to a violation. Sanctions, after being dropped under the final deal, will be difficult to reinstate in time to be useful, unless Iran’s violation is egregious. A military strike may be the sole remedy. A strike, which is widely viewed as unlikely now, will be less so in the future, after attention shifts elsewhere.

It would be better not to have a final deal than to have an inadequate one.

For the United States and its allies, not having a deal would avoid dropping the sanctions they have devoted several years to building up, and would preserve sanctions as an alternative to war. Not having a deal also would avoid bolstering the Iranian regime, which would remain vulnerable to unrest caused by sanctions. Not having a deal would avoid as well the burden of having to convince allies not to acquire sensitive nuclear technologies, thus preserving U.S. nonproliferation standards. And not having a deal would avoid the procurement dilemma caused by legitimizing Iran’s decision to enrich uranium and operate a heavy water reactor.

At the same time, it may be difficult to recapture the momentum on sanctions that existed before the latest round of negotiations. If the negotiations fall through, Congress probably would enact more sanctions, which the United States and its allies would work to enforce. However, some countries may be less willing than before to follow suit. Iran won several important concessions through the interim accord, including acknowledgement of its right to pursue uranium enrichment, acceptance of a heavy water reactor, and legitimization of the rationale that all of this work is part of a peaceful nuclear effort.

The United States should take the time to achieve a final deal that is adequate, rather than make a deal quickly.

The U.S. administration appears to want a final deal before the midterm elections in November for fear that a new Congress may be less receptive to a deal than the present one, and in order to be able to point to a foreign policy victory. On the Iranian side, President Hassan Rouhani would like to deliver soon on his promise of sanctions relief, to quell opposition at home. Therefore, both sides have an incentive to strike a deal quickly. On the key issues of uranium enrichment and completion of the heavy water reactor, the United States seems to have already made major concessions. Questions about nuclear weapon-related research are mentioned in the interim accord but have not been a focus of negotiations so far.

The United States should not now, in an attempt to finish a deal quickly, concede on the essential elements described above. In particular, it should not concede on the need for Iran to give a full explanation of its past efforts linked to nuclear weaponry. That explanation is crucial to determining Iran’s true intention. The participants expressed concern that the United States now seems unwilling to press for all the key elements within the current negotiations. It would be a mistake to focus mainly on increasing the time for breakout – from three to six, or twelve months – which the United States now seems to be doing. Such an extension is less important than other issues, and is not important enough on its own to merit additional concessions.

Katzman, Kenneth, David Kay, John Lauder, Michael Singh and William Tobey. "A Final Deal with Iran: Filling the Gaps." Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control, Washington, D.C. April 25, 2014.

The full text of this publication is available in the link below.