Former President Bill Clinton reflected on the foreign policy challenges of his presidency at the inaugural Stephen W. Bosworth Memorial Lecture in Diplomacy, hosted Wednesday by the Harvard Kennedy School.

The virtual event was the first in a lecture series sponsored by the Future of Diplomacy Project at the Kennedy School to honor the legacy of the late Ambassador Stephen W. Bosworth, who served as ambassador to South Korea under Clinton.

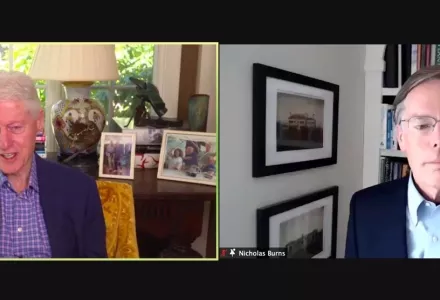

After opening remarks by University President Lawrence S. Bacow, Kennedy School professor R. Nicholas Burns interviewed Clinton about the diplomatic issues he confronted in his two terms in office.

Clinton said he believed America had “unprecedented” influence in the world at the time he entered the White House in 1993.

“I thought it was my job to try to build a world that America would be happy to be a leader in, but could no longer dominate — a world that could be as safe and fruitful as possible for the people of our country, and as many other countries as we could persuade that we should work together,” he said.

Clinton also spoke about his approach to diplomacy with Russia, which became an independent country after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“Russia was really important to me, because it’s a great country with a storied history, and they were in bad shape when I took office,” he said. “I didn’t think that humiliation was a very good strategy. I thought we needed to help them build in a positive way.”

He also reflected on his strategy towards U.S. relations with China, noting that the U.S. “has no choice but to work with them.”

“With China, our ‘work for the best, prepare for the worst’ scenario means that we have to do everything we can to cooperate with them in fighting climate change,” he said. “There are lots of win-win solutions there that may reduce tensions everywhere.”

In response to a student question about the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, Clinton noted the need to assume that there will be other infectious diseases that spread throughout our “interdependent world” in the future.

He said public health “ought to become an integral part of our foreign and domestic diplomatic policy,” and expressed hopes that young people will want to be a part of “building an International Health Corps.”

Clinton also reflected on Bosworth’s legacy and described the ambassador’s bipartisan outlook as “the total psychological opposite to what we see today.”

“This us-and-them business is killing us in America,” he said. “And it’s bad business for diplomacy.”

In a statement after the event, Burns — himself a former U.S. Ambassador to NATO and to Greece — also described Bosworth as “the ultimate diplomat.”

“He believed that America could succeed through diplomacy — through the peaceful resolution of disputes,” he wrote. “He was a listener who also believed we had to show respect toward other countries and find a way to resolve the most difficult disputes — on the Korean Peninsula and elsewhere.”

The purpose of the event was threefold, according to Burns: to honor Bosworth, share wisdom from Clinton, and highlight the critical importance of diplomacy.

“We hoped to elevate in the minds of the Harvard community the importance of diplomacy and the need for the U.S. to make a greater commitment to it,” he wrote.

The full text of this publication is available via Harvard Crimson.