Introduction

The sanctions debate is, once again, in full bloom. Thanks to Iran’s budding nuclear program and the intransigence of Tehran thus far, policymakers and pundits are again pondering the utility of sanctions. Amid a flurry of sanctions activity at the U.S. Department of Treasury, in Congress, at the UN, and overseas, the question persists: ‘‘Do sanctions work?’’

This question is hardly new. In the 1990s, the end of the Cold War and the rise of U.S. dominance led to a sharp increase in the use of sanctions, as Congress felt less inhibited in encroaching on the president in foreign policy, and as the United States tried to use its economic might to advance international goals. State sponsors of terror, suspected proliferators, weapons traders, human rights abusers, coup enactors, human traffickers, civil war instigators_nearly every foreign policy challenge_seemed to call for sanctions. By the end of that decade, however, many foreign policy stalwarts lamented the poor record of these tools, calling them ‘‘chicken soup diplomacy’’ or ‘‘feel good’’ foreign policy.1 Many concluded that imposing sanctions did little more than satisfy the U.S. desire to take action and inoculate the United States against accusations of indifference in the face of situations that were intolerable, but whose strategic import did not warrant a more robust response.

Read the full article:

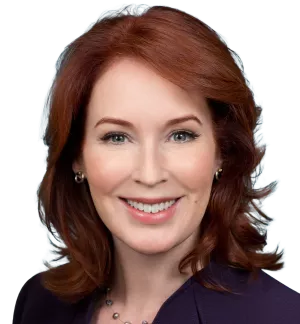

O'Sullivan, Meghan. “Iran and the Great Sanctions Debate.” Washington Quarterly, October 2010