Egypt’s decision last month to stop selling natural gas to Israel could be a harbinger of increasingly confrontational Egyptian-Israeli relations, an indication of a worsening Egyptian economy, or both.

In any case, the end of the arrangement, which provided 40 percent of Israel’s supply, suggests the need for more Israeli creative thinking and assertive diplomacy -- not with Egypt but, counterintuitively, with Turkey and Lebanon.

The Egyptian move would have raised greater concerns just a few years ago than it does today among Israelis, who import 70 percent of natural gas and all of their oil. Then, Israel saw no alternative to a near-complete dependence on other countries to meet its energy needs.

Discoveries of large underwater gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean, however, have changed Israel’s energy prospects almost overnight. In 2009, a consortium of U.S. and Israeli companies discovered the Tamar field about 50 miles off the Israeli coast, with an estimated 8.3 trillion cubic feet of gas. A year later, a similar consortium discovered Leviathan, a huge field nearby estimated to hold 16 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

Strategic Game-Changers

These finds, and the prospect of more in adjacent waters, could be strategic game-changers for Israel. A 2010 U.S. Geological Survey study estimated that the Levant Basin off the coast of Syria, Lebanon, Israel and the Gaza Strip could hold about 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil, 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas and 5 billion barrels of natural gas liquids. If true, Israel could meet its own electricity needs in the future and possibly become a net exporter to a gas-thirsty region. This would bring economic and political benefits as well as regional clout at a time when Israel’s regional standing is more uncertain than it has been for decades.

But, because nothing is simple in the Middle East, there is also a real threat that these gas discoveries could serve as a spur for conflict rather than economic growth. The Tamar and Leviathan discoveries are generally accepted to fall within Israel’s exclusive economic zone in the Mediterranean, although Lebanon originally insisted that Leviathan crosses into its waters. Exploration continues, and it could be only a matter of time before a field is discovered straddling contested boundaries.

Imagine a scenario in which a new field is found in Israeli waters but bleeds into the 330-square-mile disputed area where Israel and Lebanon’s claimed economic zones overlap. It could also run into Cypriot territorial waters. Suddenly, the world could face a situation in which Turkey insists that the field not be developed until the problem of a divided Cyprus is resolved, while Hezbollah threatens to take military action against what it sees as an Israeli effort to commandeer Lebanese national resources. (In December 2010, Hezbollah stated that it wouldn’t allow Israel to “plunder Lebanon’s maritime assets.”) The U.S. would be pulled in two directions -- one by its NATO ally Turkey, the other by Israel.

It is just this scenario that dozens of students considered in a recent competition I supervised for Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The students, looking for ways to resolve this problem, came up with two broadly different approaches.

Politics Before Economics

The first is the politics-before-economics pathway, which posits that the regional conflicts need to be resolved before the gas can be developed. This model assumes that companies are unlikely to make multibillion-dollar investments in a situation of acute political uncertainty. Depending on the location of the drilling, the extraction operations could face threats ranging from Hezbollah rockets to Turkish naval incursions. The complicated nature of gas extraction, which requires capital- intensive infrastructure such as pipelines or liquefied natural gas facilities, means that there would be plentiful targets for sabotage. (The Arish-Ashkelon pipeline, carrying gas from Egypt to Israel, was attacked 10 times last year.)

Moreover, the economics of the investment would need to make sense solely in the context of Israel’s domestic-energy market -- and perhaps Jordan’s -- because exports northward and beyond to Europe wouldn’t be feasible so long as Lebanon and Turkey objected to Israel’s plans.

The optimist in all of us might say that the prospects of plentiful, economical gas should be enough to push conflicts to resolution. Israel and Lebanon, currently in a state of frozen war, should be able to resolve their differences, agree on maritime (and land) borders, and negotiate a mechanism for the shared exploitation and commercialization of the gas. After all, Lebanon, which is 99 percent dependent on imports for its gas, could be a huge beneficiary of this peace.

One might also hope that the lure of energy riches would bring about an equally historic resolution of the Cyprus conflict, under which the Republic of Cyprus, an EU member, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus come to agreement on the terms of their coexistence. Such progress on Cyprus could provide a boost to the Israeli-Turkish relations, which have been on a negative trajectory since the Gaza flotilla incident in May 2010. If sufficient, gas developed in the eastern Mediterranean could flow through Turkey, and on to Europe, helping lessen Turkey’s dependence on Russian gas and bolstering its ambitions to become an energy corridor.

This potential outcome of sweetness and light should motivate American and other diplomats who may find themselves involved in mediating crises in the Levant. But optimism should be tempered by reality. One need only look to the Caspian Sea -- where five bordering states have failed to agree on boundaries for years -- to see how waiting to resolve territorial disputes can stall development of natural resources.

Agreeing to Disagree

Fortunately -- as the students I worked with pointed out -- there is an alternative to waiting for a complete resolution of longstanding conflicts. This less-obvious route involves more limited bargains, which don’t demand final resolution of complex territorial and political disputes.

Israel and Lebanon -- as well as Cyprus and Turkey, if necessary -- might agree to disagree. They might choose a limited accord in which each side states that it does not relinquish any of its claims or withdraw any of its grievances, but agrees to start developing the gas and oil fields following agreed-upon guidelines, pending final resolution of the big political issues.

Historical examples suggest this model is viable. In 1979, Malaysia and Thailand agreed to a joint development arrangement to exploit the resources of their continental shelf, setting aside “the question of delimitation of the Gulf of Thailand for a period of fifty years.” More recently, the 2003 Timor Sea Treaty between East Timor and Australia pushed off the settlement of boundaries for 50 years in order to open the door for resource development under agreed terms.

Even in the Middle East, there have been some precedents, if less-successful ones. In 1971, Iran and the United Arab Emirate of Sharjah, feuding over control of the island of Abu Musa, agreed to a joint resource-development plan, but stated that that pact shouldn’t be interpreted to suggest that either “Iran nor Sharjah will give up its claim to Abu Musa nor recognize the other’s claim.”

These precedents suggest a less ambitious approach to developing eastern Mediterranean gas is worth exploring if more comprehensive peace efforts prove impossible at the time. Too often, politics trumps economics in the Middle East. Let this time be an exception.

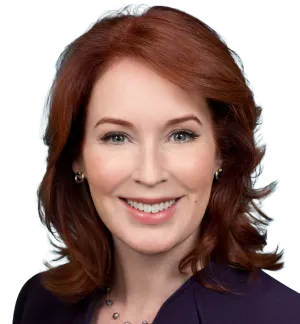

O'Sullivan, Meghan. “Israel’s Undersea Gas Bonanza May Spur Mideastern Strife.” Bloomberg Opinion, May 21, 2012