How U.S. Law Enforcement Expanded its Extraterritorial Reach to Counter WMD Proliferation Networks

Download the Full Report

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Martin Malin, Matt Bunn, Will Tobey, Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, Steven E. Miller, Robert Shaw, and Kenneth MacDonald, as well as those law enforcement and intelligence professionals who wish to remain nameless, for their helpful comments. The authors would also like to thank Jacob Carozza and Humza Jilani, who assisted with the editing and preparation of the report, as well as Amber Morgan and Alex O'Neill for assistance with background research efforts. Research for this report was supported by grants from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Table of Contents:

- Executive Summary

- Findings and Recommendations

- Report Organization

- Section 1: Cutting off the Supply of WMD Technology

- U.S. Coordination and Capacity Building Efforts

- Domestic U.S. Authorities for Counterproliferation Law Enforcement

- Domestic U.S. Implementation and Enforcement

- Summary

- Section 2: Overseas Counterproliferation Investigations and Operations

- Counterproliferation and the Challenge of Jurisdiction

- U.S. Legal Dimensions of Extraterritoriality

- U.S. Extraterritorial Counterproliferation Operations

- The Intersection of Law Enforcement and Regulation

- Implications of Expanding Law Enforcement Counterproliferation Extraterritoriality

- Section 3: Recommendations and Conclusions

- Enhancing Domestic Integration and Collaboration

- Maintaining both Capability and Legitimacy

- Increasing Financial Transparency

- Conclusion

- Conclusion

-

Notes

Executive Summary

The networks of middlemen and intermediaries involved in the illicit procurement of weapons of mass destruction (WMD)-related goods and technologies often operate outside of the United States, which presents several legal and political challenges regarding U.S. trade control enforcement activities. This report considers the extraterritorial efforts of U.S. law enforcement in counterproliferation-related activities and their implications. In other words, how does the United States contend with violations of its weapons of mass destruction (WMD)-related trade controls in overseas jurisdictions, and what are the implications for broader U.S. and international nonproliferation efforts, as well as wider international security and economic concerns?

In recent decades, North Korea and Iran have demonstrated a keen ability to exploit lax governance and oversight in various countries to illicitly procure WMD-related and dual-use goods and technologies—i.e., goods and technologies that have both WMD and civilian applications—in the international marketplace. Even countries with sophisticated indigenous capabilities, like China, India, and Pakistan, continue to illicitly procure these goods and technologies through black and grey markets. Illicit suppliers and middlemen, for example, have frequently used circuitous routes, acquiring goods through third countries and transshipping them in order to avoid the scrutiny of law enforcement, intelligence, and regulatory agencies. In order to address these gaps, the United States, in concert with international partners, has taken significant steps to ensure states make concrete commitments to implement supply-side controls in order to prevent the spread of WMD-related goods and technologies. The United States has promoted stronger controls on illicit trade through law enforcement and intelligence cooperation, industry outreach, and capacity-building and training efforts. In principle, while other countries face similar challenges with extraterritorial enforcement, the United States has been the most aggressive.

Despite international commitments to implementing national trade controls, significant gaps in financial, supply-chain, and logistical systems remain, mainly due to political and legal differences between foreign jurisdictions. In response, U.S. law enforcement has adopted a wide range of counterproliferation activities to contend with jurisdictional hurdles. Take, for example, the case of Karl Lee—a “principal contributor” to Iran’s ballistic missile program. Karl Lee (aka Li Fang Wei) is a China-based businessman who, since the early 2000s, according to U.S. prosecutors, supplied Iran’s ballistic missile program with advanced technologies and controlled materials, such as graphite, specialty metal alloys, gyroscopes, accelerometers, and various machine tools and manufacturing equipment. Some of the goods, like graphite, appear to have been produced in his factory located in Dalian, China. In 2014, open source records suggested that Lee expanded his manufacturing operations beyond graphite, to include fiber optic gyroscopes—a critical component used in missile guidance systems.1 The Karl Lee case helps to illustrate a particularly tough problem when it comes to WMD proliferation: jurisdiction. That is, what can the United States do to counter networks and middlemen that traffic in WMD-related goods and technologies who are located in foreign jurisdictions where authorities are unwilling to work with U.S. officials or their allies?

Findings and Recommendations

This report finds that while conducting extraterritorial enforcement demonstrates a strong commitment to controlling the spread of WMD-related goods and technology and that U.S. tools and efforts in this area are expanding, such actions can also erode trust and may undermine efforts to ensure consistent implementation of trade control norms and obligations, such as those found in UN Security Council Resolution 1540.

Overall, this report recommends that the United States should work toward finding a balance between extraterritorial law enforcement activities and ensuring a consistent and multilateral approach to global nonproliferation objectives—especially for implementing global strategic trade controls. In order to enhance U.S. counterproliferation efforts in this area, we make three general recommendations:

- Recommendation 1. Currently, counterproliferation-related law enforcement activities are spread across several agencies of the U.S. government with few points of integration. The inter-agency mechanisms that do exist for coordination—like the Export Enforcement Coordination Center—are limited in terms of scope, participation, and funding. Moreover, the United States lacks a national counterproliferation law enforcement strategy. Consequently, enforcement —at times—can appear ad hoc and produce counterproductive results concerning broader nonproliferation goals and objectives. In order to more effectively coordinate extraterritorial enforcement activities, the Trump administration should appoint a director for counterproliferation law enforcement on the National Security Council staff, under the Senior Director for nonproliferation, responsible for developing a national strategy that integrates broader U.S. and international counterproliferation objectives. The director should also conduct a comprehensive assessment of U.S. counterproliferation law enforcement activities, focusing on ways to reduce redundancy and overlap by increasing information-sharing and coordination. Such an assessment should also explore ways to maximize the efficacy of inter-agency cooperation.

- Recommendation 2. The United States must calibrate its extraterritorial enforcement efforts in order to prevent overuse and ensure future capability. As a consequence of U.S. unilateral sanctions policies, countries and non-state actors are adapting to minimize and mitigate exposure to U.S. legal and regulatory risks. Extraterritorial law enforcement actions may contribute to this trend and ultimately undermine broader U.S. and international nonproliferation objectives and commitments, as well as broader international security and economic concerns. Instead, preference should be given to options that make use of official legal procedures while adhering to international rules and norms, in the service of nonproliferation objectives that enjoy international support—like adherence to and implementation of Resolution 1540. Multilateral cooperation should remain a cornerstone of U.S. counterproliferation efforts. The Department of State, in concert with the Departments of Treasury and Justice, should work to update bilateral legal assistance treaties to incorporate legal definitions and standards consistent with contemporary interpretations of jurisdiction for export controls and nonproliferation objectives.

- Recommendation 3. Finally, the United States should continue to focus on deterring, preventing, and disrupting illicit procurement networks by taking broader steps to constrain proliferators’ use of “enabling institutions,” such as secrecy jurisdictions within the United States and overseas. It is essential that U.S. counterproliferation law enforcement continue to examine and question its assumptions and conventional wisdom about the nature of illicit procurement. A practical law enforcement approach needs to be based on a sound understanding of the causes and consequences of illicit procurement, to include: motivations, modus operandi, and processes of adaptation.

Report Organization

Using open source information, interviews with current and former law enforcement officials, and reviews of court records and proceedings, this report provides a detailed assessment of current U.S. law enforcement efforts for countering WMD proliferation, the legal and political challenges the United States faces, and the implications of U.S. enforcement efforts for broader nonproliferation, foreign policy, and economic goals. In Section 1 we review the U.S. and international commitments to implement supply-side controls to prevent the spread of WMD-related goods and technologies and highlight current gaps and challenges. Section 2 considers U.S. law enforcement efforts to counter proliferation activities that occur in foreign jurisdictions. These include undercover and sting operations, the use of lure techniques, information operations, as well as new tools at the nexus between law enforcement and regulation. Section 2 concludes with a discussion of how these tools may impact broader nonproliferation efforts. Finally, section 3 offers recommendations to enhance law enforcement for counterproliferation while avoiding potential unintended consequences of increased extraterritorial enforcement.

Section 1: Cutting off the Supply of WMD Technology

History has repeatedly shown that states seeking WMD have relied—at least partially—on acquiring foreign materials and technologies.2 During the 1980s and 1990s, for example, Pakistan and Iraq covertly sourced sensitive nuclear enrichment components from international suppliers.3 According to recent United Nations (UN) reports, North Korea continues to supply its nuclear and ballistic missile programs from foreign manufacturers, despite strict international sanctions regimes and trade controls.4 Although Iran agreed to curb its nuclear program following the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the country continues to illicitly procure foreign materials for use in its ballistic missiles.5

Given states’ apparent and persistent need to source WMD-related goods and technologies from foreign suppliers, beyond a keen interest in curbing the demand for WMD, policymakers have focused a great deal of attention on supply-side controls (e.g., multilateral and national export-controls, targeted financial sanctions regimes, and embargoes, among other legal and regulatory actions). At the very least, restricting the supply of critical equipment, technology, and materials may be a useful stop-gap to curbing demand—albeit, one more likely to slow rather than prevent the eventual success of a WMD program.6 Although this report does not directly address the efficacy of multilateral supply-side regimes, it is essential to understand the general scope and parameters of the regimes. Equally, export controls are one facet of a layered and multidimensional regime that requires cooperation and coordination among diplomatic, intelligence, regulatory, law enforcement, and commercial resources.7 Within this landscape, enforcement represents a narrow range of activities—extraterritorial enforcement is even more narrow. However, given the significant power and reach of U.S. enforcement efforts, it is important to fully understand how the United States has approached enforcement, its evolution, and its potential unintended consequences for other intelligence, law enforcement, and diplomatic efforts.

Early on in the post-WWII years, the United States and its allies recognized the importance of controlling exports of strategic goods and technologies. Established in 1949, the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom) was one of the first informal arrangements between Western powers to deny strategic technologies to the then-Soviet Union. To be sure, many viewed the CoCom as nothing more than a “gentleman’s handshake” with little or no authority to address violations—most of which were dealt with in secret.8 Although the CoCom ceased its operations by 1994, several multilateral and international arrangements, including the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), and the Australia Group, have emerged and endured as supplier states have increasingly harmonized their export controls.9

As global trade and commerce boomed throughout the 1990s, controlling proliferation-sensitive goods and technologies required increasing levels of cooperation and coordination among diverse political, legal, and regulatory systems. Different concepts of ownership and jurisdiction (i.e., what a country considers as part of its legal territory), as well as different political and policy objectives, have frustrated states’ efforts to form an international consensus on what should and should not be controlled, and more broadly constrained the implementation of supply-side measures.10 For example, it was not until 1992 that the Nuclear Suppliers Group included dual-use goods and technologies in its guidelines (i.e., goods and technologies that could make a “major contribution to an unsafeguarded nuclear fuel cycle or nuclear explosive,” but also have non-nuclear uses).11

As A.Q. Khan’s nuclear proliferation network unraveled in the early 2000s, it was clear that global export control regimes—at the time—were unprepared to deal with non-state WMD proliferation. His network employed layers of middlemen, suppliers, and financiers from Europe and South East Asia to the Middle East in order to acquire, manufacture, and sell nuclear enrichment technologies, weapons plans, and other dual-use goods to Iran, Libya, and North Korea.12 The Nuclear Suppliers Group, the Australia Group, the Missile Technology Control Regime, and the Wassenaar Arrangement were each informal, multilateral agreements between states that provided guidelines and established norms for implementing domestic legislation, administrative procedures, and conducting enforcement mechanisms consistent with requirements spelled out in international nonproliferation treaties.13 These regimes, however, were not legally binding, failed to keep pace with rapid globalization and the spread of dual-use goods and technologies, and ignored the emerging role of the non-state actor in WMD proliferation.14

By May 2003, the Bush administration began to explore options to address non-state WMD proliferation and assemble support for broader international commitments. One of the first efforts was the U.S.-led Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), which was a non-legally binding agreement between members to accept a set of principles concerning interdicting shipments potentially related to WMD trafficking. Initially only 40 members, PSI membership now totals 105. However, as some have pointed out, although PSI improved coordination and communication between international counterproliferation efforts, it did not address several legal challenges.15 Eventually, Bush administration officials moved to put forward a UN resolution that would mandate countries to address WMD proliferation threats—namely by criminalizing the proliferation of WMD and putting into place national export control systems. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1540, adopted in 2004, requires all member states to implement “appropriate effective” domestic rules and regulations—including export controls, border controls, physical protection of nuclear materials, and financial controls—to prevent the spread of WMD technologies to non-state actors.16 These requirements, in theory, form a baseline level allowing states to implement country-specific UN sanctions.

U.S. Coordination and Capacity Building Efforts

Although not the focus of this report, it is important to highlight U.S. outreach, capacity-building, and other diplomatic efforts to ensure states’ compliance with UNSCR 1540 goals and objectives. A key criticism of UNSCR 1540 is that although the Resolution is legally binding, it lacks an enforcement mechanism. Thus, from a governance perspective, it is incumbent on states with robust supply-side controls to assist weaker states. In the United States, for example, the State Department’s Export Control and Related Border Security Program (EXBS) has provided technical assistance, training and outreach to more than sixty countries with varying degrees of success. The Department of Energy conducts outreach and technical assistance to help states secure materials and implement nuclear smuggling detection and deterrence programs along borders.17 The Department of Commerce works with foreign companies to implement rigorous corporate compliance and due diligence programs for export controls.18

However, this approach is still inadequate to address non-compliant and non-cooperative states. In fact, the United States has taken coercive tactics when presented with egregious issues of non-compliance. For example, the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia both implemented national export legislations in 2007 and 2010, respectively, but only after coming under threat of sanctions by the United States.

Fourteen years after the adoption of UNSCR 1540, several states continue to fall behind in implementing the Resolution’s obligations.19 According to the most recent UN report, 137 of 193 member states have put into place nuclear export control legislation, meaning more than 50 states have not done so. Only 60 states have catch-all provisions in their export control laws (i.e., rules and regulations governing goods and technologies that do not fall under an export control regime) and only 84 states have legal authorities that address transshipment (i.e., shipping goods to a third-party jurisdiction before being shipped to its final destination).20 Vague guidance on the more than 300 requirements of the resolution, as well as concerns about the Resolution’s applicability to national goals and objectives, undermine implementation efforts.21

Two key themes have emerged to explain states’ failure to act. The first suggests that states see strategic trade controls as self-limiting and potentially harmful to their national economic and security interests. The second theme suggests that a lack of national capacity, limited capability and resources, and various bureaucratic and political constraints impede the implementation of trade controls.

In an early study of national export control systems, Cupitt et al. proposed a framework, based on an economic-rationalist perspective, to describe the conditions when states are likely to implement internationally compatible export controls.22 The framework attempts to explain why states implement export control systems in terms of maximizing the political and economic benefits of belonging to a liberal international community. The authors conclude that resource constraints and the political costs of administering a national export control systems account for a “considerable portion of the policy variance” between countries, rather than the particular government’s perception of external security threats posed by WMD-related illicit trade and proliferation.23

In a more recent study, Stinnett et al. discuss states’ compliance with UN Security Council Resolution 1540 from two perspectives: external pressure and capacity.24 Whereas the former perspective explains compliance as a consequence of national interest and external pressures, the capacity perspective emphasizes limitations in the technical and bureaucratic capabilities of governments.25 In an analysis of thirty countries, the authors found significant evidence to support the limited capacity explanation for states’ willingness to implement its UNSCR 1540 obligations. The authors found no support for the hypothesis that states with economies that rely heavily on exports would have greater economic incentives not to implement 1540 obligations or the hypothesis that strategic partnerships with the United States are associated with “more aggressive nonproliferation efforts.”26 These findings are generally consistent with an earlier study of UNSCR 1540 compliance by Fuhrmann, who finds that compliance is strongly associated with both political willingness and capacity.27

In addition to Resolution 1540 obligations, there are several other international agreements—both legally binding and non-legally binding—that address threats stemming from WMD-related proliferation. Several UN sanctions regimes, for example, require member states to enact measures to detect, prevent, and stop certain financial transactions, as well as implement trade restrictions related to WMD proliferation. UN Resolutions in 2006 required member states to prevent the export of nuclear, missile and military technologies to North Korea.28 Subsequent UN Resolutions have broadened the measures against North Korea significantly to include trade embargoes on coal and other goods, financial sanctions, and maritime restrictions on North Korean shipping.29 However, as with Resolution 1540, compliance with UN sanctions regimes and enforcement can vary significantly—even though the UN sanctions are legally binding measures.

In the case of North Korea, for example, Pyongyang has demonstrated a keen ability to exploit gaps in states’ sanctions implementation. According to the March 2018 UN Panel of Experts Report, North Korea’s illicit networks traded in banned goods through China, Mexico, Russia, and the Philippines, among several others.30 They established front companies in jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, Australia, Hong Kong, China, and Malaysia, as well as brokering services in Australia, Angola, Egypt, Italy, and Japan.31 To finance illegal trade and commerce—including military sales to Mozambique and Namibia and ballistic missile technology to Syria—Pyongyang’s agents built banking relationships throughout China, Russia, Libya, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia.32 The sheer number of countries involved in these recent evasion efforts illustrate both the scope of North Korean activities and that all countries could potentially be exploited in proliferation networks.

Other multilateral commitments have dealt issues that run parallel to WMD proliferation—like proliferation financing and money laundering. Since 2012, for example, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which is an inter-governmental body established in 1989 that promotes the implementation of global anti-money laundering standards, has recommended that states implement targeted financial sanctions, “…to comply with United Nations Security Council resolutions relating to the prevention, suppression, and disruption of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and its financing.”33 Such recommendations are increasingly important as the international community turns to targeted financial and economic sanctions to punish states engaged in WMD proliferation. Much like Resolution 1540, however, international controls on the financing of proliferation are fragmented and vary widely by state.34 Some countries, like Singapore, have extensive legislation that criminalizes the financing of proliferation, specifically. Others only implement controls based on entity lists, thus leaving room for proliferators and sanctions evaders to obfuscate payments by other means.35

To summarize, while there is a range of international and multilateral agreements to control the spread of WMD-related goods and technologies, they are often weak, rarely legally binding, and, in many cases, vague. Consequently, the United States has developed counterproliferation practices that seek to address these gaps that emerge beyond traditional U.S. jurisdictions. The next section describes the primary statutory authorities that criminalize WMD proliferation-related activities.

Domestic U.S. Authorities for Counterproliferation Law Enforcement

In the broadest sense, U.S. counterproliferation efforts seek to discourage interest in pursuing WMD, prevent efforts to acquire WMD or related technologies, roll back existing programs, and deter WMD use by possessor states by leveraging defense, intelligence, diplomatic, and law enforcement capabilities.36 Although many statutes address the domestic and international security concerns of WMD proliferation, the following describes the primary criminal and civil legal authorities and regulations available to U.S. law enforcement agencies.37

The Atomic Energy Act (AEA). The AEA, which Congress passed in 1956 (amending the 1946 Atomic Energy Act), lays out the cornerstone policies of the United States for both civilian and military use of nuclear technologies. The Act makes anyone who “…willfully violates, attempts to violate, or conspires to violate…” its provisions subject to criminal prosecution. The Act also makes it illegal for “…for any person, inside or outside of the United States, to knowingly participate in the development of, manufacture, produce, transfer, acquire, receive, possess, import, export, or use, or possess and threaten to use, any atomic weapon.” The criminal penalties are specified in 42 U.S.C, Chapter 23, section 2272. Depending on the criminal act and the magnitude of harm, penalties can range from fines up to $2 million to a life sentence in prison.

The Arms Export Control Act (AECA). Enacted in June 1976, the AECA gives the president authority to control and regulate the export and import of military-related goods. Although the AECA is focused mainly on military-related trade, the Act does oblige the president to prohibit sales to any country that—after August 1977—delivers or receives “nuclear reprocessing equipment, materials, or technology to any other country” or is a “non-nuclear-weapon state which, on or after August 8, 1985, exports illegally… from the United States any material, equipment, or technology which would contribute significantly to the ability of such country to manufacture a nuclear explosive device…” The AECA makes it a crime to “…willfully, in a registration or license application or required report, make any untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading…” Most of these provisions are implemented through the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). Violations of section 2278, which detail licensing and munitions list requirements, are punishable by up to a $1 million fine and twenty years in prison.

The Export Control Reform Act (ECRA). Signed in 2018 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act, the ECRA is the newest fixture of U.S. export control legislation that permanently enacts significant portions of the 1979 Export Administration Act (EAA), which had expired in 1994.38 In addition to giving the president authorities to maintain export control lists, the Act also requires the Administration to identify and regulate “emerging and foundational technologies of concern,” in addition to other licensing administration functions. Regarding enforcement, the ECRA makes it a crime for someone who “…knowingly violates or conspires to or attempts to violate any provision… or any regulation, order, or license issued thereunder…” In other words, violations of the implementing regulations carry criminal and civil penalties, which range from up to a $1 million fine and ten years in prison. The ECRA also includes civil penalties for violations, which can include fines up to $300,000 or the revocation of export privileges. Also, the ECRA expands law enforcement authorities for the Department of Commerce. The Agency can now use possible violations of the ECRA as a predicate offense to obtain search warrants, conduct undercover operations, conduct both domestic and foreign investigations, and make arrests. These authorities are now consistent with other law enforcement agencies, like the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). First signed in 1977, IEEPA provides the president sweeping authorities to regulate international transactions in times of national security crises. Prior to IEEPA, the president used authorities under the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act to regulate international trade and commerce in times of national crisis. The problem, however, was that the 1917 Act was not entirely clear regarding its scope and duration.39 Practically, IEEPA and the Trading with the Enemy Act are the same, but with one notable difference. While the United States must be in a state of war for the president to regulate trade and commerce under the Trading with the Enemy Act, the president has complete discretion to declare a national emergency under IEEPA. The only requirement is that the emergency is an “unusual and extraordinary” threat that emanates in whole or substantially outside of the United States. What exactly constitutes “unusual” or “extraordinary,” however, is up for interpretation. Once the president declares a threat, he or she can investigate, regulate, or prohibit a range of transactions and economic activities with few exceptions. The exceptions primarily relate to humanitarian aid and education materials. Per the statute—not the corresponding implementing regulations—violations or conspiracy to violate IEEPA can result in criminal penalties including fines up to $1 million and up to twenty years in prison. Violating IEEPA is also a predicate offense for many financial crimes, like money laundering. This means IEEPA violations can also incur money laundering charges, which have far stiffer penalties. There are also civil penalties associated with IEEPA violations, including fines up to $250,000.

Supporting Legislation and Executive Actions. IEEPA is by far the most commonly used legal authority to impose restrictions against WMD proliferators—both state and non-state actors—primarily due to the flexibility and power it provides the president.40 In 1994, for example, President Clinton signed Executive Order 12938, which declared the proliferation of WMD to be an “unusual and extraordinary” threat to the United States, and directed Federal agencies to develop policies to control exports of WMD-related goods and technologies, as well as impose sanctions on states that stockpile or use chemical or biological weapons. In 2005, President Bush expanded the scope of the executive order by imposing sanctions on foreign persons that “…have engaged, or attempted to engage, in activities or transactions that have materially contributed to, or pose a risk of materially contributing to, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction or their means of delivery…”41 Violations of these executive orders, among many others, are governed under IEEPA penalties.

In addition to executive orders, several pieces of Congressional legislation also rely on IEEPA, AECA, and EAA (now ECRA) authorities to provide a legal basis for criminal and civil penalties. The 1996 Iran Sanctions Act (as amended), for example, specifically targets Iran’s energy sector, as well as persons who export, transfer, or transship military and weapons-related goods and services. Under the Act, the President can use IEEPA authorities to impose a range of economic restrictions.

The 2010 Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act (CISADA) also permits the President to leverage IEEPA authorities to target Iran’s banking and finance sectors. In addition to prohibiting most imports from Iran, the Act also imposes IEEPA-based restrictions—issued by the Secretary of the Treasury—that bar U.S. banks from opening correspondent accounts with any foreign financial institution that facilitate Iran’s WMD or nuclear program.42

Domestic U.S. Implementation and Enforcement

U.S. national authorities responsible for enforcing counterproliferation-related rules and regulations are spread across more than a dozen agencies, offices, and inter-agency organizations. Below we highlight the key agencies and offices with law enforcement authorities to investigate and prosecute WMD proliferation-related violations or with regulatory functions that may impact enforcement.

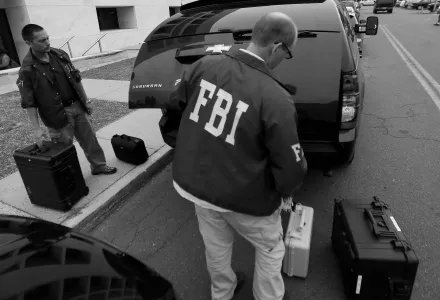

Federal Bureau of Investigation. In July 2011, the FBI established the Counterproliferation Center (CPC) to combat the spread of WMD and other technologies. As part of the agency’s Counterintelligence Directorate, the CPC draws upon both intelligence and law enforcement authorities to facilitate proliferation-related investigations and operations worldwide. These include violations of the Arms Export Control Act, Export Administration Act, Trading with the Enemy Act, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

Department of Homeland Security. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) is in charge of the agency’s Counterproliferation Investigations Program, which is responsible for investigating and preventing “…sensitive U.S. technologies and weapons from reaching terrorists, criminal organizations and foreign adversaries.” According to ICE, HSI has the broadest investigative and enforcement authorities for issues dealing with export laws. The statutory authorities include the Arms Export Control Act, the Export Administration Act, the International Economic Emergency Powers Act, as well as other statutes that deal with smuggling and trafficking.

ICE is also the steward of the inter-agency Export Enforcement Coordination Center (E2C2), which it serves as the primary coordinating hub for all federal export control-related investigations and operations. In November 2010, President Obama established the E2C2 under Executive Order 13558—largely a result of a 2006 Government Accountability Office report that highlighted several gaps and inefficiencies in U.S. export control enforcement systems.43 In addition to coordinating information between agencies, the E2C2 also serves to reconcile and resolve investigative and operational issues that may arise, act as the primary conduit between law enforcement and the intelligence communities, coordinate public outreach, and establish government-wide reporting and tracking databases. Participating agencies include the Departments of Commerce, Defense, Energy, Homeland Security, Justice, State, Treasury, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) provides support to the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI)—a global effort that began in 2003 aimed at stopping the trafficking of WMD, their delivery systems, and related materials. States participating in the PSI agree to many commitments, including interdicting the transfers to and from states and non-state actors, developing mechanisms to facilitate information exchanges, and strengthening national legal authorities to facilitate interdictions. Although the State Department provides the outward facing point of contact, for its part, CBP applies its full range of enforcement and investigative authorities in support of PSI. These include targeting and analysis, inspection and detention, intelligence and information sharing, and industry outreach.

Department of Commerce. Within the Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security, the Office of Export Enforcement (OEE) is responsible for investigating and prosecuting export control violations, as well as conducting industry outreach and training. The OEE also maintains stewardship of the Sentinel program, which ensures compliance by conducting end-user verification checks and educational outreach to foreign trade groups.

As part of the 2018 Export Control Reform Act, the Department of Commerce received new legal authorities to enhance its investigations and operations, including the use of undercover employees. Before the 2018 Act, the Department of Commerce had the authority to carry out general investigative activities and impose administrative sanctions and civil penalties—including denying export privileges.44

Department of Justice, National Security Division. The National Security Division was established in 2006 as part of the USA PATRIOT Act reform efforts to consolidate the coordination and cooperation between prosecutors and law enforcement agencies. Within the division, the Counterintelligence and Export Control Section is responsible for supervising or coordinating the prosecution of WMD proliferation-related cases that are referred by the FBI, DHS, Commerce, and other agencies.

Department of the Treasury. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which is responsible for safeguarding the U.S. financial system, facilitates the collection, analysis, and dissemination of financial intelligence to U.S. law enforcement. Much of this intelligence is collected through regulatory reporting requirements under the Bank Secrecy Act (i.e., Currency Transaction Reports, Suspicious Activity Reports, and Reports of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts). Although FinCEN does not possess law enforcement authorities similar to the FBI or DHS/HSI, its intelligence and analysis functions are critical to furthering counterproliferation investigations and operations. FinCEN also has the authority to make “Section 314” requests on behalf of investigators. Section 314 of the USA PATRIOT Act permits FinCEN to query U.S. financial institutions for transactional information on persons of interest for the purpose of running down leads (i.e., Section 314 requests are not a substitution for obtaining a subpoena).

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is responsible for implementing and administering U.S. sanctions regimes. Acting under national emergency powers authorized by the president, as well as specific sanctions legislation, OFAC has the authority to conduct civil investigations and enforcement actions against sanctions violators and provide assistance to other federal, state, and local law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Although OFAC does not investigate or prosecute criminal violations, the office works closely with law enforcement and intelligence agencies to develop sanctions packages, designating particular individuals and entities for sanctions enforcement. It is often the case, for example, that OFAC relies on law enforcement and intelligence information to justify its sanctions recommendations. Also, a designation can provide the necessary legal underpinning to pursue criminal or administrative action against a violator. For example, if OFAC designates an entity under Executive Order 13382, “Blocking Property of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferators and Their Supporters,” Federal law enforcement can pursue criminal or civil charges based on the underlying IEEPA statute.

Intelligence. While the focus of this report is on extraterritorial law enforcement, it is important to recognize the close integration and cooperation between the law enforcement and intelligence communities on matters related to export controls and WMD proliferation. The National Counterproliferation Center (NCPC), which is under the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, is the primary hub for coordinating intelligence activities to counter nuclear, chemical, and biological proliferation and their means of delivery. The NCPC also acts as a critical interface with U.S. law enforcement agencies. Other intelligence agencies and offices with counterproliferation missions that closely coordinate with law enforcement include National Security Agency, S2G (counterproliferation); Central Intelligence Agency, Strategic Interdiction Group; and Defense Intelligence Agency, Defense Counterproliferation.

Summary

In addition to the diplomatic initiatives to curb international demand for WMD and reinforce nonproliferation norms, supply-side approaches have remained a staple of U.S. efforts to stem the spread of WMD proliferation-sensitive goods and technologies. In general, U.S. law enforcement agencies—with support from intelligence and diplomatic agencies—share the responsibility for investigating and prosecuting violations of U.S. WMD-related export controls.

While the United States continues to be a global leader in terms of its political and legal commitments to counterproliferation, U.S. enforcement efforts are complex and fragmented. As illustrated above, investigations and operations are spread over several federal agencies. In some cases, there is considerable overlap between agencies. The FBI and DHS Homeland Security Investigations, for example, share the same legal authorities to investigate export control violations. Although inter-agency groups, like the Export Enforcement Coordination Center, are meant to avoid overlap and duplication, technological, bureaucratic, and sometimes legal hurdles prevent proper coordination and collaboration. A 2006 report by the Government Accountability Office specifically highlighted several impediments to greater collaboration and information sharing, like differences in case management and IT systems.45 Unfortunately, few of these issues have been adequately addressed.46

Outside of the United States, there are clear disparities in national approaches, translating into a patchwork landscape of supply-side controls. While UNSCR 1540 obliges all states to put in place national export control systems, among other requirements, the resolution provides significant leeway for each state to determine its system of national legislation, implementing authorities, and priorities. From a U.S. enforcement perspective, what happens when entities violate U.S. domestic law in foreign jurisdictions? The next section details the scope and implications of these jurisdictional hurdles regarding U.S. counterproliferation law enforcement.

Section 2: Overseas Counterproliferation Investigations and Operations

Law enforcement counterproliferation activities generally entail some level of coordination and cooperation with foreign governments, mainly due to the transnational nature of illicit procurement. This section considers the activities and legal tools that the U.S. government has deployed in its efforts to conduct export enforcement actions overseas. It considers the U.S. approaches to the jurisdictional challenge, extraterritorial counterproliferation operations, and actions at the nexus between law enforcement and regulation. Before considering these challenges and implications, the section begins by outlining the U.S. resources available to assist in these transnational investigations and enforcement operations.

Most U.S. law enforcement agencies directly involved in counterproliferation maintain an overseas presence in order to facilitate coordination with the host government. The U.S. Department of Commerce, for example, maintains Export Control Officers (ECOs) in seven foreign jurisdictions to support end-user verification programs, as well as industry outreach and training.47 In 2015, State Department and Department of Commerce officials conducted more than 1,000 end-user verifications in 55 countries.48 The Department of Homeland Security’s HSI maintains 66 offices in 49 countries as of 2017—although these resources are generally in support of broader Immigration and Customs Enforcement missions.49 Similarly, the FBI staffs 64 legal attaché offices and more than a dozen smaller offices, which provide coverage to over 200 foreign territories.50

According to one former law enforcement official, an overseas presence facilitates robust liaison relationships with local law enforcement and intelligence and is critical to ensuring successful counterproliferation investigations and operations.51 One commonly used mechanism to coordinate international law enforcement efforts is INTERPOL—an international law enforcement organization with 192 member countries. With mission areas in anti-trafficking in illicit goods and CBRNE terrorism prevention, INTERPOL facilitates legal assistance, conducts capacity-building efforts, and raises awareness of proliferation-related dangers. In many cases, the United States requests an INTERPOL “Red Notice” regarding persons trafficking in WMD-related goods and technologies.52 These notices convey relevant information about persons wanted by a member state, as well as restrict the individual’s ability to travel internationally and are considered the closest instrument to an international arrest warrant.

While liaison efforts are often ad hoc or informal arrangements between U.S. and foreign law enforcement agencies, or over specific investigations, there are also several legal agreements to help ensure due process and reciprocity between jurisdictions.53 For example, the United States currently has extradition treaties in place with over 100 countries.54 Having an extradition treaty in place, however, does not guarantee legal reciprocity, and in many cases, extradition treaties are insufficient to ensure cooperation. To supplement these treaties, the United States relies on several bilateral agreements that establish rules for each party to the agreement to exchange evidence and information in criminal and civil matters. As of 2017, the United States has approximately 50 bilateral Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) and Agreements (MLAAs), the contents of which vary between countries, but place obligations on states to assist in criminal investigations and prosecutions.55 In most cases, these agreements rely on the principle of “dual-criminality,” meaning an individual can be extradited from one country to stand trial for breaking U.S. laws only if a similar law exists in the extraditing country.

In addition to MLATs, the United States also has approximately eighty Customs Mutual Assistance Agreements (CMAAs) in place. These legal agreements, which are based upon a model developed by the World Customs Organization (WCO) and negotiated bilaterally, allow for the “exchange of information, intelligence, and documents that will ultimately assist countries in the prevention and investigation of customs offenses.”56 Although the CMAAs allow for information sharing, they “do not guarantee that U.S. law enforcement will have access to foreign persons, ports, and facilities.”57

Several other arrangements allow for the exchange and sharing of information that may be relevant to counterproliferation investigations and operations. Concerning financial information, for example, the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has several Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) to facilitate the sharing of financial intelligence between the United States and other countries’ financial intelligence units (FIUs).58 The United States is also a member of the Egmont Group, a body consisting of over 150 FIUs from different countries, which seeks to facilitate information exchange at the operational level per a set of principles and rules approved in 2013.59 In the past, however, law enforcement has been reluctant to use these mechanisms—especially in “unfriendly jurisdictions”—for fear of giving a “tip-off” to the target of the investigation or operation.

As noted above, these mechanisms facilitate law enforcement efforts for the United States around the world and supplement the intelligence operations, diplomatic initiatives, and the work of various international bodies dedicated to preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their delivery systems.

Counterproliferation and the Challenge of Jurisdiction

Perhaps the single biggest impediment to successful counterproliferation law enforcement is having to contend with the political and legal challenges of foreign jurisdictions. The jurisdictional challenge stems from the basic accepted principle of sovereignty—meaning states have the right to manage their internal affairs in accordance with their laws, norms, and customs. From the perspective of accepted international legal norms, it is generally not possible (or accepted) for one state to impose its domestic law on entities inside another state. Thus, pursuing a counterproliferation policy that addresses the transnational nature of illicit WMD procurement becomes fraught with jurisdictional challenges. Often, these challenges put elements within an illicit procurement network out of jurisdictional reach. Even when states are willing to cooperate, however, differences in national legal systems and norms can frustrate investigations and prosecutions.

Furthermore, illicit networks are adaptive entities and have been known to base their operations on assessments of local legal, regulatory, and political risk—a concept known as “jurisdictional arbitrage.”60 Savvy proliferators will deliberately base themselves in jurisdictions where the risk of detection or prosecution is low. A.Q. Khan’s illicit activities, for example, illustrate how jurisdictional shopping—in Malaysia, Turkey, South Africa, and the United Arab Emirates—can frustrate law enforcement efforts.

U.S. Legal Dimensions of Extraterritoriality

Given the transnational nature of illicit procurement, at what point does the United States consider entities and property not located within the United States within the bounds of U.S. law? International legal norms dictate interpretations of jurisdiction that can vary considerably, especially concerning extraterritorial law enforcement. Most countries base their interpretation of jurisdiction on one or more of four general principles. The first principle defines jurisdiction in terms of its geographic territory.61 Over the last several decades, however, economic globalization and the rise of international non-governmental organizations have reduced the relevance of a territory-oriented principle of jurisdiction in most cases.62 The most commonly adopted principle is the nationality principle—meaning states base jurisdiction on nationality rather than territory. Some countries, like the United States and Canada, have interpreted the nationality principle in a rather broad context to include citizens, companies, and property under its jurisdiction. This includes foreign companies that are owned or operated by U.S. entities, but otherwise located abroad, as well as companies that may only be partially owned by U.S. entities.

The last two legal dimensions of jurisdiction are the protective and universal principles. The protective principle is based on the right of a sovereign state to protect its economic and security interests.63 In this respect, claiming extraterritorial jurisdiction is consistent with international legal norms, but is substantively and arbitrarily defined by each state in terms of what constitutes a threat. Lastly, states may claim extraterritorial jurisdiction in order to enforce universal rights. This principle is mainly concerned with state violations of international law on slavery, piracy, and certain human rights violations.

Box: Nodes out of Reach: Nicholas Kaiga

In October 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice charged Belgian national Nicholas Kaiga with export violations following a multi-year undercover investigation. According to court records, Kaiga conspired with an unnamed Iranian individual to procure export-controlled aluminum tubes from the United States. The Iranian counterpart operated front companies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Malaysia, which Kaiga used to transship the goods to Iran.

Although U.S. law enforcement effectively employed undercover methods to ensnare Brussels-based Kaiga and disrupt his illicit activities, U.S. law enforcement was unable to conduct enforcement action against the Iranian elements of the network located in the UAE and Malaysia. The individual controlling the UAE and Malaysian companies, which had a limited footprint in the UAE and used a virtual office in Kuala Lumpur, appears to have been based in Iran. This case highlights the challenge of taking out nodes in proliferation networks in multi-jurisdictional law enforcement operations, and particularly when proliferators establish front companies in jurisdictions in which they are not physically based. The inability to address these nodes limits the overall effectiveness of the law enforcement actions and can leave pathways for the procurement network to reconstitute itself.

Box: Differing Laws and Legal Systems: Gotthard Lerch on Trial

In October 2008, a German court convicted and sentenced Swiss national Gotthard Lerch to more than five years in prison for his participation in A.Q. Khan’s nuclear proliferation network. According to the plea agreement, between 1999 and 2003, Lerch illegally procured and transshipped export-controlled vacuum pumps to Libya. Although Switzerland extradited Lerch to Germany in 2004, the extradition arrangements between Switzerland and Germany created several prosecutorial challenges that dragged on for four years.i

In particular, Switzerland's legal assistance treaty with Germany prohibited extradition for the prosecution of crimes that Switzerland does not also outlaw. German prosecutors wished to charge Lerch with one count of treason and two counts of export violations. At the time, however, Swiss law defined treason differently from German law—meaning Lerch could not be charged with this crime under Swiss law. German authorities were also forced to drop other serious charges involving the sale of nuclear technology because CIA and British intelligence refused to share relevant information with prosecutors. Moreover, Malaysia and South Africa refused to send associates of Lerch to testify against him. In 2008, Germany finally prosecuted Lerch for minor violations and sentenced him to time served.

Box Notes:

1. Peter Crail, “Germany Convicts Khan Associate,” Arms Control Today, November 4, 2008, https://www.armscontrol.org/print/3417 (accessed February 11, 2019); Leonard S. Spector and Egle Murauskaite, “Countering Nuclear Commodity Smuggling: A System of Systems” (James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, March 2014), p. 142

Box: Shopping for Jurisdiction: Hub Selection in the A.Q. Khan Network

Seeking to fulfill a deal struck with Libya in 1997 to provide a full gas centrifuge plant for uranium enrichment, the A.Q. Khan network looked to expand its manufacturing operations in the early 2000s. Khan eventually settled on a factory in Malaysia to manufacture key components because of Malaysia’s weak export control systems and lack of enforcement, as well as other favorable political and economic factors. The plant would eventually send tens of thousands of machined centrifuge parts to Libya, some of which international partners interdicted on the vessel, BBC China, in 2003—an event which signaled the beginning of the end of the network’s activities.

Before Malaysia, Khan rejected a number of options. Dubai—a laxly regulated environment where Khan located his central transshipment hub—was dismissed because of the lack of a skilled workforce, and because of concern that importing labor and applying for work permits would raise government interest.1 Turkey was also considered, but also dismissed because of a lack of skilled labor.2 A third location, South Africa, was dismissed because the country’s history with nuclear weapons meant that imports of specialty metals would raise concerns in exporting countries.3

Ultimately, Malaysia had many attributes making it an attractive legal jurisdiction for the operation—most notably, limited export control legislation and enforcement.4 Bukhari Sayed Abu Tahir, Khan’s right-hand man, also had personal and political connections to Malaysia. He “mixed with Malaysia’s elite” and grew close to Kamaluddin Abdullah, the son of the Malaysian Prime Minister.5 More broadly, Malaysia’s emergence as a key manufacturing hub for various industries, alongside limited oversight, meant that imports of advanced machine tools and metals would not raise red flags in exporting states.

Box Notes:

1. Catherine Collins and Douglas Frantz, Fallout: The True Story of the CIA’s Secret War on Nuclear Trafficking (New York: Free Press, 2014), p. 241.

2. Collins and Frantz, p. 241.

3. Collins and Frantz, p. 261.

4. As a former Malaysian official has noted, the Khan network’s activities did not breach Malaysian law. M. S. A. Kareem, “Implementation and Enforcement of Strategic Trade Controls in Malaysia,” Strategic Trade Review Vol. 2, No. 2 (2016), p. 108.

5. Albright, Peddling Peril, p. 134.

Problems quickly emerge, however, when a citizen in one country violates the law or threatens the security and safety of nationals in a foreign country. Under these circumstances, international norms have generally held that the extraterritorial application of the law must be through the consent of the state (i.e., the foreign jurisdiction). In practice, states give consent through multilateral or bilateral extradition agreements. Another issue arises when jurisdictional claims by one state create confusing or contradictory obligations for an individual or company headquartered in a foreign country. In other words, what happens when complying with one state’s laws comes into conflict with another state’s domestic laws?64

Between 1977 and 2001, several fundamental changes to domestic rules and regulations greatly expanded the jurisdictional reach of U.S. authorities to target overseas proliferators. In 1979, for example, Congress expanded the reach of the Export Administration Act, giving the president authority to include “persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.” Because Congress failed to specify its intent as to what jurisdiction entailed, presidents have subsequently interpreted the statute broadly to include property.65

One of the first tests of this interpretation came in December 1981, when President Ronald Reagan attempted to slow Russia’s progress on its Siberian natural gas pipeline by restricting American exports and re-exports of goods and services related to oil and gas production.66 The pipeline, which was scheduled to supply Western Europe’s energy requirements, was a politically contentious issue because it threatened to undermine the U.S. role in the region. Under the rule, Reagan banned all U.S. goods and services relating to the pipeline for export or re-export to the then-Soviet Union. Unlike previous export restrictions, however, this executive order also assumed jurisdiction over American goods already overseas or already under contract.67 Many U.S. allies saw this jurisdictional expansion as overreach and swiftly moved to protect their economic and national interests. In 1982, for example, the French government ordered its largest oil and natural gas manufacturers to proceed with shipments in direct violations of U.S. sanctions—mainly as a protest to America’s extraterritorial application of its domestic law.68 Amidst a rising tide of protests from critical economic partners, President Reagan rolled back the extraterritorial dimensions of the sanctions.69

The most significant changes to U.S. extraterritorial policy occurred after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Congressional leaders determined that amendments to existing rules and regulations could help address jurisdictional gaps, especially when dealing with terrorist financing. The U.S. Department of the Treasury would later use these new authorities against banks and other financial institutions involved in sanctions violations and WMD proliferation. First, Sections 311, 312, and 313 of the USA PATRIOT Act expanded enforcement agencies’ ability to enforce U.S. rules and regulations indirectly. Section 311, for example, gives authority to the Treasury Department to designate a foreign country (or entity) as a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern.” Once designated, the Treasury Department can impose any number of special measures, to include requiring U.S. banks to conduct enhanced due diligence of its customers’ accounts and transactions or even restrict banks from opening or maintaining a foreign financial institutions’ correspondent account.70

Finally, the USA PATRIOT Act amended IEEPA language to extend jurisdiction to both people and property. As previously mentioned, most countries adhere to the principle of nationality when determining jurisdiction, which for all intents and purposes, pertains to individuals and companies. Extending this to include property is a much broader interpretation, which gives authorities significant leverage over foreign institutions trading with U.S. banks and businesses.71

U.S. Extraterritorial Counterproliferation Operations

When cooperative efforts fail or are not feasible for political or security reasons, U.S. law enforcement agencies have employed a number of tools to target overseas proliferators. The following describes the scope of these methods and how law enforcement agencies have historically used them. Notably, this section explores U.S. operations to counter proliferation networks through undercover, sting, and lure operations, and through information operations.

Undercover, Sting, and Lure Operations. Seeking extradition for violations of U.S. federal law can be a complicated process, as states may lack sufficient legal frameworks or political will to effectuate extradition proceedings with the United States. In such cases, the U.S. law enforcement agencies resort to alternative methods. Since the 1980s, federal law enforcement has used varying degrees of deception to investigate and prosecute overseas illicit procurement networks.72

In such cases, sting and undercover operations have become commonplace investigative tools to build criminal cases. Although the use and definition of undercover operations can vary by agency, the FBI defines its undercover activities as “…any investigative activity involving the use of an assumed name or cover identity by an employee of the FBI or another Federal, state, or local law enforcement organization working with the FBI.”73 It is important to note, however, that not all Federal law enforcement agencies have the legal authority to conduct undercover or sting operations. The Department of Commerce only recently received statutory authority to conduct undercover operations in support of their mission as part of the 2018 Export Control Reform Act.

Obtaining an indictment against an overseas procurement agent is not necessarily a simple or straightforward process. U.S. prosecutors are often reluctant to indict those overseas for many reasons, but most common among those are the low likelihood of the subject being extradited to the United States and the low likelihood of obtaining a conviction if the subject is extradited. In some cases, lack of expertise or knowledge about the case contributed to the decision not to pursue an indictment. As one law enforcement official noted, the bureaucratic process of an indictment is cumbersome, and “un-indicting” someone is a far more difficult and time-intensive process.74 In other cases, political decisions can affect the decision to indict.

Once law enforcement authorities have obtained enough information to pursue an indictment, the next step is to secure an arrest, which is not always feasible if the subject is located overseas. In counterproliferation-related investigations, lure operations and INTERPOL Red Notices are common methods when hurdles to seeking extradition seem insurmountable.

As previously mentioned, Red Notices are the closest legal instrument to an international arrest warrant and can be distributed as widely or as narrowly as needed. This flexibility can help reduce concerns about adversarial governments providing a “tip-off” warning to the fugitive. If a foreign government arrests a fugitive pursuant to an INTERPOL Red Note, it is incumbent on the U.S. prosecutor to secure the required extradition documents for that specific jurisdiction, per existing treaties or that country’s domestic law.

In some cases, such as that of David Levick, an Australian individual who allegedly exported U.S. goods to Iran via Malaysian intermediaries, Australia’s extradition treaty with the United States did not cover the crimes with which he was charged.75 In another example, the U.S. extradition treaty with Singapore, which came into force more than eighty years ago in 1935—when Singapore was still part of the British Empire and before the advent of nuclear weapons or ballistic missiles—does very little to address export control concerns.76 Where national laws do not include provisions for export violations, other charges such as conspiracy or falsifying documents may be used. Having to find alternative criminal charges to facilitate cooperation is quite common in proliferation-related cases. One of the main reasons is that many of the U.S. export control laws are authorized under presidential national emergency powers, which is technically a temporary authorization. Often, foreign jurisdictions lack similar laws or are reluctant to cooperate with U.S. extradition requests based on presidential emergency authorizations.

In other cases, such as the Iranian cases described in the box below, the government of the arrested person has marshalled significant political arguments and even issued veiled threats, communicated both publicly and privately, against the extraditing governments (e.g., Thailand, the UK and Hong Kong—all of which have extradition treaties in place with the United States) in order to try and prevent extradition. Those in the crosshairs often view strategic trade controls and sanctions as politically motivated. As one former enforcement official noted, law enforcement in these areas is “more political than traditional enforcement areas.”77

Box: The Sting: Jiang Guanghou Yan

Jiang Guanghou Yan pled guilty in March 2016 for intentionally trafficking in fraudulent goods.1 Yan worked as a representative in China for a Shenzhen-based company, HK Potential. The investigation began in 2012 when industry sources provided DHS investigators information about suspicious inquiries that Yan had made during a trade show. Specifically, Yan expressed interest in the processes and techniques certain manufacturers use to detect counterfeit integrated circuits.

Eventually, law enforcement agents, acting in an undercover capacity, purchased and received several orders of integrated circuits that Yan knowingly altered to appear as if they were a higher grade. By July 2015, Yan had attempted to procure export-controlled military-grade integrated circuits, used in a variety of military applications, for shipment to China— even offering to replace the stolen parts with counterfeit parts. Yan was eventually taken into custody in December 2015 when he traveled to the United States in order to finalize the transaction. The case represents a typical undercover sting operation, targeting an individual overseas.

Box Notes:

1. “Actual Investigations of Export Control and Antiboycott Violations” (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, January 2017), p. 48.

When formal extradition efforts fail, U.S. law enforcement will often use lure operations against targets in unfriendly states. The U.S. Attorneys’ Manual defines a lure operation as using “…subterfuge to entice a criminal defendant to leave a foreign country so that he or she can be arrested in the United States, in international waters or airspace, or in a third country for subsequent extradition…”78 Such lure operations have proven successful in a number of counterproliferation-related investigations.

Interestingly, while lure operations are a preferred method of bringing a fugitive into custody when legal extradition arrangements are unavailable, the U.S. Department of Justice maintains the legal opinion that extraterritorial law enforcement activities are not prohibited even if they contravene international customary law. The FBI, for example, could make an arrest in a foreign jurisdiction without the consent of government authorities in that jurisdiction.79 Before this 1989 legal memorandum, the Justice Department considered such action to be an “…invasion of sovereignty for one country to carry out law enforcement activities within another country without that country’s consent.”80 Such cases, however, are still rare and require prior approval by the attorney general and sometimes the president.81

Information awareness campaigns. In 2013, Congress established the Transnational Organized Crime Rewards (TOCR) program, which directs the Secretary of State to issue rewards for information on those involved in transnational crime, like human trafficking, money laundering, and dealing in arms and other illicit goods.”82 The TOCR program is primarily based on a similar program for narco-traffickers, the Narcotics Reward Program, which the Department of State established in 1986.83

Box: Prisoner Swaps, Nuclear Deals, and Politics

In early 2016, the Department of Justice released seven Iranian prisoners held in the United States and dropped charges against 14 others.1 Of those released, one Iranian was incarcerated for running a network responsible for procuring U.S.-manufactured microelectronics for use in surface-to-air missiles. Another was serving eight years for conspiracy to supply Iran with satellite technology. Most of the cases that prosecutors dropped, however, involved suspects located overseas, in particular in Iran. One of the Iranians was Seyed Jamili, who procured more than 1,000 pressure transducers for Iran's nuclear program through a Chinese intermediary.2 The intermediary, Sihai Cheng, is currently serving a nine-year prison sentence for IEEPA violations.3

The release of these prisoners and dropping of these cases show how high-level political considerations can impact export enforcement. While the Obama administration claimed the move was to secure the release of American prisoners in Iran, others chided the decision as politically-motivated and connected to securing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—the agreement between Iran and world powers, which limited Iran's nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.

Box Notes:

1. Josh Meyer, “Obama’s Hidden Iran Deal Giveaway,” Politico, April 24, 2017, http://politi.co/2p8GrIa (accessed February 11, 2019).

2. A pressure transducer—also referred to as a pressure transmitter—converts pressure into an analog electrical signal. Highly calibrated pressure transducers are key centrifuge components for the enrichment process.

3. Milton J. Valencia, “Chinese Man’s Lawyers Say Iran Deal Left Client Caught in Middle,” Boston Globe, January 27, 2016

Box: Late 2000s Iranian Extradition Cases

A series of cases involving Iranian nationals in the mid-to-late 2000s provide some insights into the challenges of extraditions. During this period, Iranian procurement networks were actively seeking military-grade goods and technologies.

Jamshid Ghassemi, a high-ranking Iranian Air Force official, was arrested in Thailand in 2006 for attempting to procure accelerometers for use in missile guidance systems. Ghassemi’s defense reportedly made three arguments for his release: that U.S. extradition documents were filed too late, that Ghassemi would face torture to reveal Iranian military secrets in the United States, and that the U.S.-Thailand extradition treaty exempts “military offenses.”1 Ghassemi was released in September 2008 after Thailand denied the extradition request.

Nosratollah Tajik, a former Iranian ambassador to Jordan, faced extradition from the United Kingdom to the United States following a U.S. sting operation during which he sought to export U.S. night vision goggles to Iran. UK authorities approved the extradition request in 2007. However, the United States allegedly did not respond until 2011. Tajik appealed the order because the process had taken too long and won in 2012.2 It is important to note that during the extradition process, the UK government expressed strong concerns that Tajik’s extradition could lead to Iranian retributions against UK diplomatic staff.3

A third individual, Yousef Boushvash, was arrested in Hong Kong in 2007 following a U.S. sting operation in which he attempted to procure U.S.-origin fighter aircraft parts for Iran.4 In 2008, a Hong Kong government official noted that the authority to extradite Boushvash to the United States had been withdrawn "per instructions from the central government of the People's Republic of China."5 After release by the Hong Kong authorities, Boushvash disappeared and managed to evade U.S. authorities and an INTERPOL arrest warrant.

Box Notes:

1. John Pomfret, “U.S. Presses Thailand to Hand over Accused Russian Arms Dealer,” The Washington Post, August 19, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/08/19/AR2010081906034.html (accessed February 11, 2019).

2. Terri Judd, “Former High Ranking Iranian Diplomat Nosratollah Tajik Avoids Extradition to US,” The Independent, November 27, 2012, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/former-high-ranking-iranian-diplomat-nosratollah-tajik-avoids-extradition-to-us-8360080.html (accessed February 11, 2019).

3. American Embassy in London, “Iran: UK Intends to Go Forward on Tajik Extradition but Concerned About Safety of Its Tehran Embassy” (Department of State, June 2008), http://wikileaks.wikimee.org/cable/2008/06/08LONDON1580.html (accessed February 11, 2019). Indeed, these concerns may have been credible given the storming of the UK’s mission in Tehran in 2011 by protestors.

4. Mark Hosenball, “Back on the Black Market,” Newsweek, June 21, 2008, http://www.newsweek.com/back-black-market-90731 (accessed February 11, 2019).

5. Mark Hosenball, “U.S. Faces Setbacks on Blocking Arms Sales to Iran,” Newsweek, October 7, 2008, http://www.newsweek.com/us-faces-setbacks-blocking-arms-sales-iran-92237 (accessed February 11, 2019).

Box: Back for More: Fuyi “Frank” Sun

In 2011, Mr. Sun contacted an aerospace company to procure export-controlled carbon fiber to ship to China.1 Unfortunately for Sun, he had contacted a sting operation set up by the FBI to catch would-be procurement agents. During the undercover operation, FBI agents repeatedly asked Sun if he intended to apply for an export license, to which he indicated that he would. However, after failing to obtain a proper export license, Sun indicated that he intended to ship the carbon fiber to an intermediary country and then re-export the goods to China—all through an offshore company.

Although initial discussions failed because Sun felt the FBI might be monitoring his activity, it was not enough to deter him from returning to the fake aerospace company four years later in 2015 to set up additional deals. Eventually, Mr. Sun traveled to the United States in 2016 in order to meet with “representatives.” Undercover agents eventually arrested Sun after he paid agents $25,000 in cash and explained how he would repackage and mislabel the items in order to transship through Australia on to China.

Box Notes:

1. United States of America v. Fuyi Sun, aka “Frank,” 1:16-CR-00404 Southern District of New York (April 13, 2016).

Thus far, U.S. law enforcement authorities have used the TOCR program against only one WMD proliferator—Chinese national Li Fangwei (aka Karl Lee).84 The State Department’s reward for Lee’s capture also coincided with the issuance of an FBI “Wanted” poster. He is listed in the Counterintelligence section of the FBI’s website alongside nine other individuals including spies, hackers, and intellectual property thieves. The U.S. State Department also placed a $5 million bounty for information leading to Lee’s arrest as part of its Transnational Organized Crime Rewards Program.

While “Wanted” posters and rewards programs are not necessarily extraterritorial applications of U.S. domestic law, they are useful tools for raising awareness in foreign territories. Law enforcement agencies, like the FBI, have used “Wanted” posters since the 1920s— famously depicting gangsters like “Pretty Boy” Floyd and John Dillinger, to Osama bin Laden. It is unknown, however, how effective these programs are for counterproliferation. Karl Lee received little attention in the Chinese press after the U.S. imposed sanctions and issued its criminal indictment. Coupled with the Red Notice, however, such programs serve to not only raise awareness but limit Lee’s travel. It is also possible that rewards programs and increased transparency compel Lee to alter his business operations in such a way as to provide an opportunity for law enforcement to take action—perhaps by undermining trust within his organization.85

The Intersection of Law Enforcement and Regulation

The most common methods of disrupting proliferation network activities today exploit the structure of international financial systems. They range from targeted sanctions and banking regulations to the use of civil and criminal courts. In some cases, these tools allow enforcement agencies to gather critical intelligence to identify key network nodes and members, while other tools can disrupt the network directly by blocking access to the U.S. financial system or through seizures of proliferator assets.