Science and innovation are increasingly being recognised as key sources of economic renewal around the world. This awareness is creating new social demands on institutions such as universities and national research institutes.

The challenge, therefore, is in reforming these institutions so that they can take on contemporary economic, social and environmental missions.

The most damaging legacy of the African system of higher education is the separation between research, training and practical activities. Research is generally carried out in institutes that do not enrol students.

Universities, on the other hand, do little research of direct relevance to society. Much of the development work is undertaken by local communities, non-governmental organisations, and Government officials will little technical experience.

Conventional responses to this challenge include seeking more funding for universities, strengthening collaboration between universities and the productive sector, and increasing student access to research institutes and the private sector.

Bureaucratic resistance

Such proposals, however commendable, fall short of the radical steps needed to bring research, training and operational activities under the same institutions.

This problem is compounded by the fact that these related functions fall under different ministries, and efforts to rationalise them often meets with bureaucratic resistance and even outright political hostility.

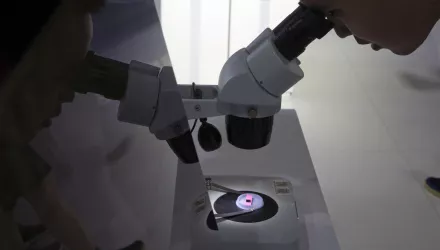

Take the health sector, for example. Health research is often carried out in national institutes that are separate from medical schools and hospitals. What is needed to improve Africa’s healthcare systems is to establish "research and training hospitals" by merging existing functions in research institutes, medical schools and hospitals.

Similarly, agricultural research and training functions should be merged and linked directly to farming communities. Other areas that can benefit from such synergies include engineering and infrastructure development.

Building new roads, ports, harbours, railways and telecommunications facilities, for example, could strengthen engineering education and promote the development of small and medium-sized enterprises.

Other areas that could benefit from such linkages include environmental management. East Africa could benefit hugely from a regional wildlife research university directly linked to the tourism sector. The university can help to incubate private and social enterprises that not only help to expand economic opportunities, but also contribute to environmental management.

Introducing such reforms will require high-level executive leadership. In Malaysia, for example, Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi is taking person interest in helping to strengthen the role of teaching hospitals as a key part of the country’s healthcare system.

In light of its leadership in this area, the United Nations University has established its new International Institute for Global Health at Kabangsaan University in Kuala Lumpur.

New policies that require medical schools to own hospitals can help to strengthen such political leadership. Analogous policies also need to be adopted for agricultural, industrial and environmental sectors.

Other long-term measures include providing tax incentives to private individuals and firms that create and run technical institutes. An example of such an approach is the support provided by Samsung in the creation of the Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine in Korea in 1997.

Mobile phone firms such Safaricom and Celtel could be encouraged to consolidate their charitable contributions and create a new generation of university-level schools that serve their skill needs as well as the needs of the wider society.

Some of their senior staff would be highly qualified to serve as adjunct faculty of the schools. Traditional engineering and agricultural firms operating in the region can play a similar role.

Bringing together research, training and practice under the same institutions require new management approaches that give equal standing to researchers, academics and practitioners. It takes appropriate governance systems and leadership skills that focus on professional integration as a guiding principle.

Efforts to bring higher education to the service of community development will need to be accompanied by reforms in the overall functioning of government.

Kagame's wise leadership

More specifically, presidential offices will need to equip themselves with the capacity to manage technical knowledge as key inputs into development. In other words, these offices will need to get smarter than they are today.

A good example of wise leadership is that of President Paul Kagame of Rwanda who appointed Minister Romain Murenzi in his office to be in charge of matters related to science, technology and innovation.

Rwanda’s vision is based on real successes on the ground, which include the critical role the Kigali Institute of Science, Technology and Management has played in the country’s reconstruction after the genocide.

It is expected that other African presidents will follow this visionary leadership as they prepare for the first summit of African presidents on science and innovation to be held in Addis Ababa in January, 2007.

The growing interest in science and innovation among African leaders is commendable. But bringing practical utility to scholarship should be the ultimate test of academic excellence in Africa.

Prof Juma teaches the Practice of International Development at Harvard University and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.

Juma, Calestous. “Merge Academia with Scientific Research.” The Daily Nation, June 13, 2006