A Principled and Pragmatic Approach to Promote Human Rights and Pursue Denuclearization

Acknowledgements

Between April and July of this year, our working group engaged in robust discussions with the singular goal of recommending a pragmatic, solutions-oriented policy on North Korea to the Biden administration. The recommendations in this report are derived from the collective and varied experiences and insights of the US-NK Policy Working Group. Our working group members—some of whom have analyzed and observed North Korea since 1979—include former U.S. Army and U.S. Navy officers with extensive experience in security affairs on the Korean peninsula, retired U.S. intelligence community analysts, academics, and human rights NGO leaders. Our birth places include the U.S., South Korea, North Korea, and Romania. Two of our members secretly listened to American and other foreign radio programs in Romania and North Korea before eventually settling in the United States.

Firstly, I am deeply grateful to our working group members who voluntarily spent countless hours on this project: Guy Arrigoni, Markus Garlauskas, Hyun-Seung Lee, David Maxwell, John Park, Greg Scarlatoiu, Sue Mi Terry, and Skip Vincenzo. Furthermore, I am so grateful to everyone who reviewed iterations of this report and provided advice based on lived experiences in North Korea, and knowledge gained from working in various capacities in the U.S. government: Andrew Kim, Jim Kelman, Matt Armstrong, Will Tobey, Seongmin Lee, Choongkwon Park, and Paul Thomas. A special note of gratitude to the reviewers who prefer to remain anonymous. Thank you to Benjamin Fu, a student at Harvard College, for your enthusiastic support on this project.

Thank you to the Belfer Center and the Stanton Foundation for supporting my fellowship, which enabled me to pursue this project. Special thanks to Andrew Facini and the incredible communications team for shaping this report in a way that the readers could view more enjoyably. Lastly, thank you to Professor Graham Allison for supporting this endeavor from the beginning to end.

It is the hope of this group that the proposed policies and ideas in this report will spark debate, garner support, and play a role in shaping more peaceful and secure relations between the governments and people of the United States, its allies, and North Korea.

—Jieun Baek, Convener and Author, US-NK Policy Working Group

Executive Summary

The North Korean nuclear threat remains one of the most persistent and complex foreign policy issues facing the United States today. The growing risk that the Kim regime’s nuclear and missile programs pose to the U.S. underscores the need to consider every tool of statecraft available to pursue the United States’ policy objectives on North Korea.

The Biden administration has emphasized the importance of alliances and core values of democracy in its foreign policy approach. Given this emphasis, public diplomacy—activities intended to understand, inform, and influence foreign audiences—should be considered an essential tool in achieving our long-term policy objectives in North Korea. Public diplomacy has the potential to spur domestic change in North Korea—change that could result in improved human rights conditions, leading to behavioral change in the Kim regime, and eventually denuclearization.

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan has said, “[the US’] policy towards North Korea is not aimed at hostility. It’s aimed at solutions.”1 A solutions-oriented policy seeks long-term solutions. We believe that public diplomacy is the most effective means available for the United States to incrementally help foster conditions in the long term that could lead to the Kim regime becoming more accountable to its people and voluntarily pursuing denuclearization. These conditions are unlikely to occur without the transformation of relations between the regime and its people.

The overarching goal of a public diplomacy policy with North Korea should be to provide diverse and truthful content and messaging that helps to foster change from within that leads to a different and freer country. Public diplomacy could help to fundamentally transform the domestic environment of North Korea,2 which could in turn create conditions conducive to the U.S. advancing its long-term policy goal of denuclearization of North Korea. Public diplomacy would also bolster other policy instruments designed to shape the regime’s behavior, including diplomacy, sanctions, and UN resolutions.

Seeking to induce changes in the regime’s behavior is not a new strategy, with economic sanctions being the preferred tool. However, sanctions are only one avenue for promoting a change in behavior. Public diplomacy could significantly widen the bandwidth of pressure into an area the regime is most vulnerable to—internal pressure. The United States’ current public diplomacy efforts should be expanded to encourage North Koreans to broaden their perspectives and foster change.

What we are proposing is not a tall ask. The people, ideas, mechanisms, and theories of change to implement an effective public diplomacy policy all presently exist inside and outside of the USG. If the USG were to provide both resource support and the policy top cover that resource-constrained public diplomacy efforts need to operate, the return on investment to U.S. national security interests and policy objectives in North Korea would be tremendous.

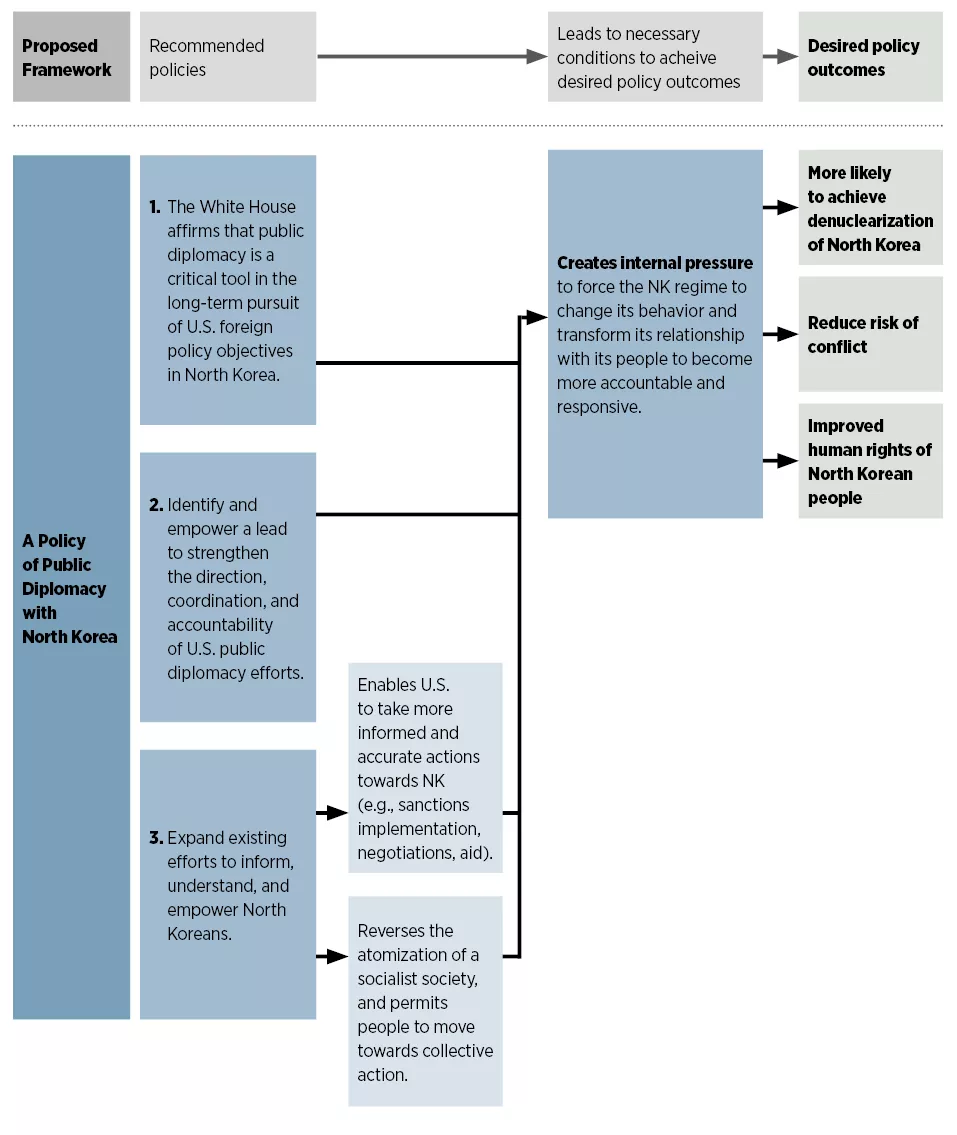

This report proposes three recommendations for how the USG can adopt a public diplomacy policy with North Korea:

Recommendation 1: The White House affirm that public diplomacy is a critical tool in the long-term pursuit of U.S. foreign policy objectives in North Korea.

Recommendation 2: Identify and empower a lead to strengthen the direction, coordination, and accountability of U.S. public diplomacy efforts on North Korea.

Recommendation 3: Expand existing efforts to inform, understand, and empower North Koreans.

Preamble

The North Korean nuclear threat is an intractable problem that will only grow in scale and complexity unless North Korea dramatically alters the program’s trajectory. North Korea’s nuclear capabilities continue to potentially (1) compromise our interests on the Korean peninsula and beyond; (2) make the United States vulnerable to nuclear threat; (3) undermine our credibility and security interests in Asia, and (4) make our allies susceptible to nuclear coercion. It is reasonable to assume, absent some fundamental change in Pyongyang’s worldview, that North Korea will continue to develop its nuclear arsenal and engage in acts of coercion, proliferation, and other illicit activities.

Once North Korea can more credibly threaten American cities with nuclear attack, we believe that the United States, the Republic of Korea (ROK), Japan, and the broader international community will be significantly more vulnerable to nuclear coercion. The consequence of this probable scenario would likely be a significant weakening of America’s credibility, an erosion of the U.S.-ROK alliance, and/or conflict in the region. The growing risk that the Kim regime’s nuclear and missile programs pose to the United States underscores the clear need for a different approach.

This report is predicated on the U.S. policy objectives expressed by key figures in the Biden Administration. In his remarks during the U.S.-ROK Foreign and Defense Ministerial press conference, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin stated that, “We are committed to the denuclearization of North Korea, reducing the broader threat the DPRK poses to the United States and our allies, and improving the lives of all Koreans, including the people of North Korea who continue to suffer widespread and systematic abuses at the hands of their repressive government.”3

President Biden has also placed a renewed focus on prioritizing North Korean human rights. In his first overseas trip, Secretary of State Blinken said in Seoul, “President Biden has been very clear from day one that he was determined to put human rights and democracy back at the center of American foreign policy. North Korea, unfortunately, is one of the most egregious human rights situations that we know around the world.”4

While denuclearization has consistently remained the United States’ policy priority on North Korea, the promotion of human rights has historically been less of a priority. In the past, promoting human rights in North Korea has been treated as a policy goal, leveraged as a pressure tactic, or neglected altogether under the presumption that it might anger the Kim regime and therefore interfere with nuclear negotiations. Moreover, some advocates of denuclearization argue that human rights abuses are ultimately a domestic problem of North Korea and therefore should not be pursued as a U.S. policy goal, especially if it comes at the expense of nuclear negotiations.

However, we must recognize that North Korea’s nuclear program and the government’s systematic abuses of its own people’s human rights are inseparable. North Korea would not be anywhere near their current level of nuclear capability if the regime did not chronically deprive its population of resources and engage in systematic abuses of human rights.5 If it did not engage in such abuses against its own people (a practice that has put all three dynastic leaders in a state of perpetual paranoia of internal threats), then the Kim regime would not be so fearful of external interference in its internal affairs, which has helped to lead it to prioritize nuclear weapons over its population’s well-being. Had there been a more informed and coordinated citizenry and unconstrained access to outside information, North Korea’s domestic and international environment would most likely look very different from what it is today, potentially leading Pyongyang to embrace a different set of priorities.

Kim Jong-Un is incentivized to prevent the introduction of reform into his country due to the fear that revelations of his and his family’s crimes will lead to his downfall. Jung Pak (current Deputy Assistant Secretary of State in the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs) said at Brookings in 2018, “Indoctrination at such a scale is necessary because Kim fears his people more than he fears the United States. The people are his most proximate threat to the regime.”6 Similarly, Jong-Ho Ri (a former senior economic official in North Korea) stated that the “North Korean dictator fears that opening its doors will reveal the crimes against humanity and collapse a power system wrapped up in lies and deception.”7 Pak’s and Ri’s comments emphasize that absent an impetus for the regime to transform its relationship with its people, the regime will most likely never do so on its own. In other words, unless the Kim regime fundamentally—albeit slowly—changes the way it treats its people, it will never change the way it maintains its control. Without such change, the needs and desires of North Korea’s people are unlikely to affect the regime’s priorities. This means that, absent such change, the regime would never have a strong incentive to denuclearize, even if denuclearization would tremendously benefit North Korea’s people and economy.

The North Korea problem is unique in that the solution to its nuclear problem and human rights crisis is the same, which is to compel the regime to fundamentally change its relationship with its people. We argue that a policy of public diplomacy that is intended to inform and influence North Koreans could fundamentally transform the domestic environment of North Korea. This transformed environment, in turn, would incrementally create conditions conducive to the United States achieving our objectives in North Korea. This policy of public diplomacy would mutually reinforce other policy instruments designed to shape the regime’s behavior, including diplomacy, sanctions, and UN resolutions.

Recognizing the challenges that North Korea poses, the only realistic and sustainable long-term solution that the United States should pursue is to promote internal conditions that convince the regime that it needs to incrementally and fundamentally change its relationship with the North Korean people. While clearly not easy or without risk, the North Korean regime must become more accountable and responsive to its people and move towards a society where people are empowered and have better protected human rights.

We are not advocating for regime change. Rather, a transformed environment inside North Korea would be more conducive to achieving U.S. policy objectives of denuclearizing North Korea and promoting the human rights of its people. A regime that is more accountable to its people would place a lower priority on nuclear capabilities, pose less of a threat to the United States and our allies, pose less of a threat to its own people, and be able to more openly engage and integrate with the international community. A regime that is accountable to its people is more likely to be accountable to other nations. If North Korea changes, it would have the opportunity to become a full member of the international community, which would have vast benefits for the people of North Korea. Pyongyang could make that choice, but only if a greater degree of accountability to the North Korean people makes it in its interest to do so.

We began our online working group discussions by reviewing the following set of operating assumptions. These operating assumptions provided a firm basis for the policy recommendations in this report.

- The United States should not accept North Korea as a nuclear weapons state. If the United States and our allies were to accept North Korea as a nuclear state, Kim is likely to perceive his strategy to be successful and has no incentive to change path.

- Meaningful and voluntary denuclearization will not occur under Kim Jong-Un’s current style of rule.8

- Even within the constraints of international sanctions, North Korea’s nuclear and missile arsenal will most likely continue to grow in quality and quantity.

A Policy of Public Diplomacy with North Korea

“A Policy of Public Diplomacy with North Korea” offers three recommendations for how the United States can persuade the North Korean regime to transform its relationship with its people and its position on nuclear weapons—two seemingly separate yet deeply linked matters. The direct and indirect products of these changes directly affect U.S. foreign policy objectives in North Korea and the region. This report proposes three recommendations for how the USG can adopt a public diplomacy policy with North Korea—explained in more detail further below:

- The White House affirm that public diplomacy is a critical tool in the long-term pursuit of U.S. foreign policy objectives in North Korea.

- Identify and empower a lead to strengthen the direction, coordination, and accountability of U.S. public diplomacy efforts.

- Expand existing efforts to inform, understand, and empower North Koreans.

Public diplomacy-based change over time is the best tool to create the conditions to induce North Korea to better respect the rights of its people, increasing the prospects it will eventually accept denuclearization.Public diplomacy efforts must be intertwined with every aspect of United States’ policy priorities in North Korea, because if the current regime were to fundamentally change certain core values, the barriers to normalization would be lowered significantly. This changed environment would encourage the regime to pursue a less hostile relationship with the outside world and deescalate its nuclear program.

The most effective method to fundamentally change the North Korean regime’s behavior and produce the United States’ desired policy outcomes is to create internal sources of pressure. To enable this pressure, information needs to get into and out of North Korea as much as information needs to travel safely within North Korea between North Koreans. Targeted public diplomacy efforts would shape the worldview and decision-making processes of North Koreans (both elites and non-elites), which would then create internal pressure to compel the regime to change its behavior. While external pressure from sanctions and other coercive measures may constrain the regime’s behavior, to date this strategy has failed to fundamentally change the regime’s behavior in a way that aligns with U.S. national security interests and international norms.

An approach that uses public diplomacy to shape North Korea’s domestic environment through direct and indirect engagement with its people must be a priority if the U.S. is to achieve its long-term policy goals in North Korea. This would benefit the United States, its allies, and the people of North Korea in the long term.

Why North Korean Human Rights Is Critical to U.S. Policy on North Korea

U.S. national security issue

A government that is a systematic abuser of its population typically behaves in other arenas that do not align with our national security interests. Kim denies human rights to North Koreans as an effective means to stay in power and maintain the regime in its current state. But if the regime is compelled to fundamentally transform its relationship with its people, the United States could deal with a reformed North Korean state that may be more willing to negotiate away its nuclear weapons, less dependent on illicit activities and human rights abuses, and more likely to behave as a normal state—all of which would enable them to more easily integrate into the global community of nations.

Furthermore, the USG visibly leading international efforts to promote human rights and public diplomacy efforts for North Koreans would help to counter the extreme anti-American indoctrination in North Korea. As stated in the UN COI report, “There are two basic themes central to the North Korean indoctrination programme. One is to instil utmost loyalty and commitment towards the Supreme Leader. The other is to instil hostility and deep hatred towards Japan, the United States of America (USA), and the Republic of Korea (ROK).”9 This reversal of the perception of the United States will be critical when the time comes to deal with a reformed North Korean state where domestic popular opinions factor into the government’s decision-making processes. By creating favorable views of the United States among North Koreans now, the U.S. would also be preparing the groundwork for the entire Korean peninsula as its future ally.

Bedrock of U.S. foreign policy

Human rights issues are a valid central policy reason to engage with a country. When the relationship between a government and its people is predatory, the United States has historically pressured and encouraged the government to change its behavior. Improvements of human rights in North Korea must remain a policy objective, rather than a tactical consideration. This issue needs to be at the forefront of American policy, holding a co-equal status of significance with denuclearization and other security matters.

The human rights crisis in North Korea has always been a bipartisan issue in the United States. Troublingly, there have recently been growing rifts in the U.S. Congress as North Korean human rights have begun to be politicized in the United States. Lobbying groups have been strongly propounding misguided policy recommendations to U.S. representatives in an attempt to lessen the focus on human rights and lift sanctions prematurely. The politicization of human rights in North Korea is a deeply concerning development on an issue that was—and ought to remain—a bipartisan issue anchored in what are some of the best values and foreign policy traditions of the United States.10

Recommendations:

A Policy of Public Diplomacy with North Korea

North Koreans live in the most repressive, isolated society in the world, and the government’s monopolization of information, in large part, enables it to exert nearly complete control over its population. This is a state that “ensure[s] as little exposure to knowledge which contradicts information that is propagated through state-controlled media and other means of indoctrination and information control.”11 Given the undermining effect that citizens’ consumption of unauthorized content has on the regime’s authority, the regime has dedicated significant resources to block inflows of unauthorized content, and instituted severe penalties on citizens for consuming information that range from high fines and sentences to political prison camps and even public execution.12

Yet despite such extreme efforts of the North Korean regime to block foreign content, both ‘ordinary’ and elite North Koreans risk their lives to learn more about the world outside of their country. Due to this domestic demand for foreign and unauthorized content, foreign information and media have been trickling into the country and consequently have been sparking irreversible social changes throughout the country. However, the increasingly prohibitive information environment under Kim Jong-Un could reverse this trend.13

While there have been several U.S. and South Korean government-funded radio programs that target North Koreans, most information dissemination efforts have been led by under-resourced, small NGOs, based mainly in South Korea and the United States. If piecemeal, small-scale efforts across a fractured landscape of NGOs and civil society actors could produce such changes inside North Korea to date, a U.S. policy to pursue public diplomacy with North Korea could yield incredibly powerful results.

A successful policy of public diplomacy that provides diverse and truthful content and messaging to targeted audiences in North Korea could help convince people to prefer and demand a different and freer country for themselves. In North Korea, where power is so centralized around Kim and the Korea Workers’ Party, it is critical to shape the elites’ decision-making processes and to incentivize them to push for a system that is more accountable to the people. The content and messaging should provide credible hope, awareness, and empowerment for a future that is better than the environment North Koreans live in today. The following section provides detailed and targeted recommendations.

Recommendation 1: The White House affirm that public diplomacy is a critical tool in the long-term pursuit of U.S. foreign policy objectives in North Korea.

The White House’s affirmation and prioritization of public diplomacy as a central feature of U.S. policy towards North Korea will drive the integration, support, and expansion of related efforts that are ongoing within the USG. Prioritizing this issue and implementing this policy will require resources and authorization given to key figures in the Biden administration and the U.S. Congress. Many of the ideas and talented, relevant personnel needed to operationalize this policy recommendation already exist within and outside the USG. With senior-level authorization and government resources, the payoff for enhancing mainly public diplomacy efforts into North Korea will serve U.S. national interests well in pursuing its long-term policy objectives in North Korea.

National Security Advisor Sullivan said that “[the US’] policy towards North Korea is not aimed at hostility. It’s aimed at solutions. It’s aimed at ultimately achieving the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.”14 A solutions-oriented policy is one that seeks long-term solutions, and a robust policy of public diplomacy is uniquely suited to focus on the long term.

A policy of public diplomacy would allow the United States to pursue a long-term solution to the North Korea challenge that extends beyond a presidential administration term. This is critical because 1) the security costs of not pursuing long-term solutions are too high, and 2) only a long-term solution will fundamentally address the core challenges with North Korea, a nuclear-armed dictatorship that continues to threaten the United States’ national security and drive wedges in its important alliances.

First, the United States should pursue a long-term approach towards North Korea because the security risks are too great to continue with short-term tactics that merely manage the nuclear North Korea problem. Pursuing a “managing North Korea” approach and addressing only crises and symptoms of the North Korean nuclear threat allows North Korea to buy more time to develop their nuclear arsenal, increasing thethreat to the United States and its allies. If the U.S. does not rethink its approach, North Korea may be able to credibly hold the United States, South Korea, and other neighbors of the Korean peninsula hostage through nuclear blackmail. Additionally, North Korea will only continue to depend on illicit activities and evade sanctions to generate revenue.

Second, only long-term solutions can address the fundamental problem of the North Korean issue. Short-term solutions are not an effective means of influencing a totalitarian regime that is committed to its current style of rule, one that requires total control over its people, maintains a nuclear arsenal aimed at the United States, and is committed to driving wedges between the United States’ important alliances and its evolving relationship with China.

In addition to the need to seek a long-term solution, the United States must break out of the ‘false binary’ approach to North Korea, where policies are selected between short term vs. longer term; engagement vs. holding a tougher stance. Our recommended approach of public diplomacy that seeks to promote long-term, sustained change within North Korea can and ought to be pursued in parallel with strategic nuclear negotiations and sanctions that take place on shorter timelines.

Multilateral and unilateral sanctions that are designed to compel the Kim regime to change its behavior have yielded limited results, in part because the regime has robustly leaned on illicit activities globally, and evaded sanctions. More importantly, no matter how much these sanctions affect the North Korean economy and the livelihoods of its people, since the Kim regime is not accountable to its people, sanctions can only apply limited pressure to the regime. The regime can even cite sanctions as examples of the external threats that justify its siege mentality, including its nuclear program and draconian internal control.

In marked contrast, information campaigns that have been implemented by small NGOs across the United States, South Korea, and elsewhere have had enormous impact in sparking irreversible changes inside North Korea. According to a female escapee from Pyongyang, “[North Korea] has changed a lot. The level of consciousness has increased, about everything from what we eat to what we think ... Media from outside is definitely causing things to change.”15 These resource-strapped information dissemination campaigns have also elicited sustained outrage from the Kim regime, sending a strong signal that the inflow of foreign information into North Korea is having significant impacts on North Korean society, impacts that the Kim regime finds to be undermining its authority.

Recommendation 2: Identify and empower a lead to strengthen the direction, coordination, and accountability of U.S. public diplomacy efforts on North Korea.

Identifying and empowering a central entity (hereinafter the “lead entity”) is key to driving coordinated, purposeful, and public diplomacy efforts aimed at North Koreans and audiences that may interact with North Koreans. This lead entity could be the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy/Public Affairs, the Bureau of East Asia and the Pacific, in the portfolio of the US’ North Korean Human Rights Envoy (once the position is filled), or the Special Representative for North Korea Policy.

The lead entity would coordinate and integrate efforts to craft clear messages and themes for segmented North Korean audiences, implement activities, and track the effectiveness of information consumption in a dynamic, iterative way. The lead could incubate an innovation cell that works with NGOs and private companies to robustly test and scale up ideas to distribute information to North Korean people.16 To more effectively distribute content into North Korea, this innovation cell could further develop diverse and robust distribution methods into North Korea that are tested, refined, and optimized over time. There are significant opportunities for developing secure information distribution methods in the domains of land, air, sea, and space. Several private organizations and NGOs already work in this space. Rather than replicate or seek to control these efforts, a public diplomacy policy might have more success by better enabling these existing efforts.

There is a plethora of ideas that NGOs have developed that could be considered and incorporated into public diplomacy efforts. To date, most information dissemination efforts have been limited to land-based smuggling routes across the North Korea-Chinese border, radio programs, and airborne activity with leaflets via the DMZ. Information distribution efforts into North Korea have been taking place for over twenty years by civil society actors, and it is important to learn lessons of successes and setbacks from these actors and their efforts. Building on the lessons learned from prior campaigns would enable the refinement of present-day efforts and is therefore as important as developing new ideas. These efforts require extensive piloting, testing, focus groups, and usability tests with North Korean escapees.

The USG should collaborate with U.S. tech companies to create effective delivery methods of information to North Korean people. Many U.S. tech companies have expressed interest in providing information to hard-to-reach places including North Korea. However, the main hesitation that companies have in providing information to North Korea is their fear of breaching U.S. sanctions.17 Many private companies do not have detailed knowledge on what they are and are not allowed to do, and therefore generally steer clear of engaging in any activities related to providing content to North Korean people. Therefore, the USG should consider partnering with American tech companies that want to provide content and information delivery methods to North Korean people; OFAC waivers and incentives could be offered to companies who do so. Lessons learned from U.S. companies’ dealings with China should guide implementation.

History reveals many cases of authoritarian countries where citizens were given more access to free information and collectively demanded more government accountability and reform. Such successful cases—including South Korea, Myanmar, Egypt, and Iran—led to the internal reorganization of a government that either transitioned into a more liberal form of governance or isolated reforms without leading to a regime collapse. There are also many lessons to be learned from other comparative contexts of highly effective information penetration efforts into closed societies, such as the Soviet Union, Cuba, Burma, Iran, and Eritrea.

The lead entity should consistently track effectiveness to calibrate and optimize public diplomacy efforts. The overarching goal of these efforts is to provide diverse and truthful content and messaging to targeted audiences in North Korea that will convince people to prefer and demand a different and freer country for themselves. It is undeniable that foreign content has powerful effects on North Korean people’s thought processes in questioning the reality in which they live; surveys, testimonies, and other qualitative evidence clearly and consistently emphasize this point.18 A quote by a North Korean female escapee from Yanggang Province captures this point: “At first I watched outside media purely out of curiosity. However, as time went by, I began to believe in the contents. It was an addictive experience. Once you start watching, you simply cannot stop.”19

To pursue this goal of providing content and messaging to North Koreans, the lead entity would be responsible for keeping a close and consistent gauge on the type of effects information is having in order to regularly refine the activities and increase impact. To optimize tailored public diplomacy efforts, there has to be clear indicators to gauge the effectiveness of specific campaigns. Harnessing the power and insights of North Korean escapees, especially recent escapees, will serve as a powerful tool to measure the effectiveness of these efforts. The criteria to measure the effectiveness of public diplomacy efforts should be continually updated and revised as information professionals apply their expertise to this project. These professionals know how to conduct target audience analysis (especially for hard-to-reach populations) and pre- and post-testing of themes and messages to gauge measures of effectiveness.

Structured analysis of indicators of effectiveness could expand on existing Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) surveys. Suggested areas to measure changes in North Korean citizens due to consuming foreign content could include changes in:

- Level of loyalty to, and belief in, the regime and Kim family

- Recognizing and harboring grievances of one’s life

- Risk tolerance to air grievances to peers and local authorities

- Desire to live in a different type of society and government

- Views of the United States and South Korea

- One’s belief that one deserves a better life

- Level to which one believes the Kim regime’s internal propaganda/narrative

- Understanding of market economy; the level of import of North Korea’s nuclear program

- Understanding of a free democratic system

Some of these effects may not materialize in immediate behavioral changes, which is why it is critical to constantly gauge what information is interesting (or not), what is in high (or low) demand, and what new content North Koreans want.

Given the challenges of accessing North Korean citizens, most efforts to measure effectiveness of foreign information have surveyed and interviewed North Korean escapees and travelers, but watching the regime’s responses could also provide helpful insights. Resource-constrained, uncoordinated information dissemination campaigns by NGOs and activists have elicited sustained outrage from the Kim regime, who recently called foreign content a “vicious cancer.”20 Such statements provide a strong signal that the inflow of foreign information into North Korea is having strong impacts on North Korean society, impacts that the Kim regime finds to be undermining its authority.

Recommendation 3: Expand efforts to inform, understand, and empower North Koreans.

Informing North Koreans

Clear goals for public diplomacy efforts aimed at segmented audiences must be set and achieved if the United States is to sufficiently pressure the North Korean regime into fundamentally transforming its relationship with the population.

To be deliberate and dynamic in reaching these goals, audience segmentation and tailoring messages to different audiences is key. Accordingly, the North Korean population should be broken down into three broad audiences, with tailored content targeting these segmented audiences: regime elite, second-tier leadership, and the broader population.21 Each of the three segmented audiences should then be further segmented for the purpose of providing tailored messaging and content. The higher status the targeted audience is, the more specific the messaging ought to be, since the targeted individuals are in positions of higher authority, and thus may be more consequential decision makers.

For example, the top elites among the party and military, along with technical specialists and scientists, should be parsed out for the purposes of targeting them with tailored messaging. They have very different backgrounds and interests than most people in North Korea, and also have more potential to affect meaningful change in their own spheres of authority. In addition, it will be critical to target university and graduate students, especially those from elite families, because they are the next generation of leaders. Another elite group to target is those living and working abroad in China, Russia, across the Middle East, and beyond, including diplomats, business professionals, and graduate students.

In terms of reaching all segments of the population, especially the non-elite majority, content that promotes market activities inside North Korea is most effective. Promotion of market activities is inseparable from efforts to enhance North Koreans’ welfare and information activities because market activities allow people to be significantly less dependent on the state. Given that domestic market activities are somewhat regime sanctioned, any public diplomacy effort that promotes gradual internal change in North Korea ought to promote ordinary citizens’ market activities inside the country. Empowering domestic market activities for ordinary North Koreans at the levels of the system that are not completely co-opted by the regime will foster incremental change and may encourage broad public support for any reform-minded elites’ initiatives, should the latter occur in the future.

The greatest breakthroughs in the improvement of North Koreans’ lives took place during and after the Arduous March (the great famine in the 1990s), when “trade or die” became the de facto motto for survival.22 To survive, citizens had no choice but to engage in illegal, capitalistic activities, signaling their lack of trust and dependence on the socialist state’s ability to provide. This collective dependence on market activities has burgeoned to the point where in present day, the majority of North Koreans depend on market activities to survive in this socialist country.23 The fact that market activities undermined the control of the regime and fostered independent thinking among people makes a strong case for providing content that can empower market activities for ordinary North Koreans.

Providing politically neutral and politically devoid information is important because the regime’s suppression of nonpolitical information has a corrosive effect on people’s attitude towards the regime. Average citizens will continue to harbor grievances against the state for blocking practical content (e.g., content about weather, public health, and food). Such content can have multiple tiers of benefit: the face value of the information, and the second-order value of the questioning that citizens will experience when the regime feels undermined by such innocuous content.

See Appendix on page 29 (in pdf; available below here) for a table of suggested themes, messages, and content.

Understanding North Koreans

The United States should strengthen mechanisms to aggregate and share open-source information about North Korea from North Korean escapees and other information seeping out of North Korea.24 By more efficiently aggregating and sharing information about North Korea from North Korean escapees, the USG could harness the collective informational power of escapees to enable more effective public diplomacy efforts and efforts of NGOs. The majority of the nearly 40,000 North Korean escapees living across the world maintain contact with North Korean citizens, and therefore possess rich, up-to-date information about the ground-level workings of the country.25 There is a clear demand among escapees, including those living in the United States, for providing information to the USG. By capturing the untapped information available about North Korea, the USG could better tailor public diplomacy efforts toward North Koreans.

In addition to escapees, some North Korean citizens who live and work abroad (including North Korean IT workers and hackers) may be willing to provide critical information, either voluntarily or for an incentive, that could inform U.S. public diplomacy efforts. Furthermore, this mechanism could elicit critical information on sanctions, North Korea’s cyber activities, shifts in leadership, and the regime’s internal policies. In particular, sanctions are an important policy area that could be implemented with more precision and impact if the USG had consistent access to inflows of information from North Korean escapees and others.

Empowering North Koreans by fostering information-sharing and safe channels of communication among North Korean people

In addition to getting information into and out of North Korea, it will be critical to foster safe channels of communication and information sharing among North Korean people. The North Korean regime continues to expend significant resources to prevent its citizens from consuming and circulating any unauthorized information. The regime is increasingly becoming more sophisticated in strengthening their abilities to monitor, censor, and surveil citizens from consuming such information.

Empowering North Koreans with the ability to safely communicate and share information is key to cultivating the conditions to pressure their government to become more responsive and accountable to its people. North Koreans who can safely communicate and share information will feel empowered to eventually mobilize and compel the government to reorganize its interests and reconsider their behavior.

Coordinating Multilateral Support for Pursuing Public Diplomacy with North Korea

For a long-term policy that pursues a transformed relationship between the North Korean regime and its people to be successful, the United States will need to provide credible assurances of support for North Koreans who want to move towards a freer, more accountable political system.26 The United States and our allies should collaboratively decide if there is political will to support a peaceful transformation inside North Korea. If this is the case, the United States should coordinate multilateral support for this policy with allies, including South Korea, Japan, the European Union, Canada, and Australia.

With the Biden administration pursuing a more robust values-based and multilateral approach to foreign policy, the timing is right for the United States to take back leadership on this issue. The United States should consider adding North Korean human rights back onto the agenda of the UN Security Council by reviving a coalition of like-minded states. This recommendation is in line with Secretary Blinken’s February 2021 press statement declaring that the United States intends to seek election for a seat on the UN Human Rights Council starting in January 2022.27 Furthermore, the USG should suggest the creation of post-UN Commission of Inquiry investigative mechanisms on North Korean human rights.

It is critical to work with the ROK on this policy. In a May 2021 joint statement, Presidents Biden and Moon announced that they “agree to redouble their commitment to democratic values, and the promotion of human rights at home and abroad ...The United States and the Republic of Korea share a vision for a region governed by democratic norms, human rights, and the rule of law at home and abroad ... We agree to work together to improve the human rights situation in the DPRK and commit to continue facilitating the provision of humanitarian aid to the neediest North Koreans.”28 No matter who the South Koreans elect for their next president in March 2022, the U.S.-ROK alliance must remember that the preservation and protection of human rights is one of the shared core values of this important alliance.

North Korea has a history of engaging in subversive actions against South Korea and continues its attempts to undermine the U.S.-ROK alliance. To address these challenges, it is critical that the alliance is in lockstep not only on the security front but also on improving rights for North Koreans. The objective of this policy is denuclearization, not regime change. Nonetheless, regime survival is not assured. And so, it is appropriate that the United States, its allies, as well as China, plan ahead. A note on this is included in the Appendix.

Conclusion

President Bill Clinton recently said that “with North Korea, you have to know what you won’t do, and you have to do everything else. You just have to keep trying.”29

It is time to test different approaches towards North Korea; the security costs and risks of the continuation of the current path are simply too high. North Korea continues to evade sanctions, generate billions in revenue through illicit activities, develop cyber capabilities, and grow its nuclear capabilities, posing a great threat to the United States and our allies.

If implemented, this emphasis on public diplomacy with North Korea could, over time, create unprecedented tensions inside North Korea and compel the Kim regime to re-evaluate its interests and transform its relationship with the people, allowing the United States to achieve our long-term objectives of denuclearization and improved human rights in North Korea.

Implementing this policy will come with predictable challenges, challenges that may raise tensions with the North Koreans in the short term. The mere mention of the term ‘human rights’ could serve as a pretext for the North Koreans to refuse to return to the negotiating table. But if this policy problem were simple, it would have been resolved decades ago.

These recommendations are not groundbreaking. In fact, they would be considered quite ordinary if the target country were any country other than North Korea. Access to information for a 25-million strong population in today’s digital era of instant communication and information-sharing should be considered an obvious provision. This is especially the case since South Korea’s population has 1.1 cell phone per capita and a 96% internet penetration rate.30

An old Chinese proverb states that “the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The next best time to plant a tree is now.” While this recommended policy should have been implemented decades ago, the next best time to do so is now.

Appendix

Diagram of a policy of public diplomacy with North Korea

Table of suggested messaging for public diplomacy efforts

| Targeted audience31 | Segments within targeted audience |

|---|---|

| Regime Elite |

|

|

Examples of goals of public diplomacy efforts Convince elites that they can gain from a scenario where the regime has a transformed relationship with the population Drive wedge between elites and Kim, and erode elites’ support of him There are long-term prospects for survival outside of NK and separate from this current regime; Need to give credible assurances to elites, should they voluntarily defect Persuade Kim that he can “better secure his personal survival by respecting the human rights of the North Korean people and agreeing to relinquish his nuclear weapons in a permanent and verifiable manner.”32 Convince elites that there will be future accountability for their actions Provide vision for children of elites who could thrive in a world with a freer North Korea |

|

| Second-Tier Leadership |

|

|

Examples of goals of public diplomacy efforts If you push the regime towards having a transformed relationship with its people, you will have a place in the new political situation on the peninsula Influence their decisions in instability scenarios (e.g., not attack South Korea despite orders) Maintain control over all WMD; don’t allow loose weapons and secure them until they can be properly safeguarded Convince them that there will be future accountability for their actions |

|

|

Examples of content Stories of Eastern European elites, and how they benefited from the post-Cold War era Toolkit for transitional justice Visions for alternatives to the status quo regarding political systems, economic systems, financial systems, social contracts, legal systems, etc. Content that names individuals guilty of crimes against humanity Content that reveals accurate information of crimes against humanity being committed in North Korea (e.g., satellite images of political prison camps, testimonies of tortured individuals) |

| Broader Population |

|

Examples of goals of public diplomacy efforts Psychologically prepare them for what comes next in a non-totalitarian society Provide content that would reduce the risks in a regime collapse scenario in the second order effects. Content that would encourage NK population and officials to think about what their lives would be like in a post-collapse scenario The international community is observing their country, and working towards providing better livelihoods for NK people Convince them to have morale and hope; The international community cares about North Korean people, feels that they are treated badly by the Kim regime, and that they should have the basic rights the rest of the world generally enjoys, such a food, freedom of movement, freedom to choose, freedom from fear, etc. |

|

Examples of content General knowledge about the outside world Truths about their country, regime, how other people in different parts of North Korea live (e.g., how their government works, corruption of the leadership) Knowledge about what their future can and will comprise (e.g., land ownership, political economy, private rights) Narratives of successful defectors Human rights violations that their state has committed against them, given the obligations that they have assumed as a state Highlight the toll that nuclear weapons program has taken on the human security/welfare of North Koreans Information that allows NK people to trade and farm better (e.g., accurate information about weather, prices, how basic tech works) |

Preemptive diplomacy to secure nuclear material in the event of instability

In his remarks to USFK planners during a briefing at the Pentagon in 1998, Kurt Campbell said, “There are two ways to approach planning for the collapse of North Korea: to be ill-prepared or to be really prepared.” 33 To be clear, we are not advocating for regime change, and so this report did not discuss regime collapse scenarios. However, what is undeniably important is to prepare for securing North Korea’s nuclear material in the event of sudden internal change. The United States and neighboring states must proactively put a coordinated, multilateral plan in place that could be executed if there comes a time to secure North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

If there were to be instability or sudden change inside North Korea, there will be a divergence in the United States’ political and security priorities, and those of the regional powers, and sharp differences in whether or how to intervene in the North and their ultimate disposition. This is why preemptive diplomacy on key issues— (1) defining the end of the Kim regime and (2) coordinating legitimate actor(s) to be first movers into a collapsed North Korea—is critical among the United States, China, South Korea, and other neighboring states.

Miscommunication, misunderstanding, and competing interests will complicate a multilateral response to a regime collapse scenario where securing nuclear weapons will be of utmost priority. The price for miscoordination could be inadvertent conflict. Therefore, our efforts to shape the political and security environment through dialogue—particularly with China, despite our ongoing tensions—prior to collapse are critical. Such efforts will provide the foundation for a coordinated, broad, and multilateral approach to managing a collapse scenario and securing nuclear weapons.

A strong public diplomacy campaign can contribute to positive outcomes in any contingency, such as conflict, war, regime collapse or unification. The themes and messages delivered through such a policy could lay the foundation for a free Korean people throughout the peninsula—a result that will be important to the outcome of any contingency.

Defining the end of the Kim regime

The United States and neighboring states must discuss and coordinate on a critical metric: how to define the political end of the Kim regime. Regardless of how the regime collapses or changes, and however the aftermath unfolds inside the country, one of the most disputed elements of any scenario will likely be the point at which the United States and surrounding powers deem the end of the Kim regime (separate from North Korea as a sovereign state). The critical threshold point for when external interventions might start taking place to deal with North Korea’s nuclear arsenal is when there will be sufficient consensus by nations that the North Korean regime has ended.

It will be highly likely that there will be disparate interpretations of this metric of if/when the regime comes to a political end. For example, South Korea—depending on their president/ruling party at the time—and the United States may define this metric in political terms. So, once there are initial signs of political discontinuity (e.g., precipitation of erosion of Kim’s control, or Kim dies without a clear successor), these countries may view the Kim regime to have ended. China, on the other hand, may define this metric very conservatively through legal definitions of sovereignty, in order to preserve North Korea as a buffer state for as long as possible until there is total evidence of near anarchy in the state.

Narrowing these gaps in potentially disparate interpretations of this metric is critical because it will inform subsequent long-term cooperation among external powers in securing North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

Perceived legitimacy of first movers into North Korea

In past cases of state collapse, there have been the immediate tasks of securing nuclear materials, establishing law and order, strengthening border control, disarming conventional weapons, deterring/defeating internal armed resistances, among others. Historical cases have shown that the efficacy of these efforts is significantly undercut when the new power (or body of powers) is not viewed as politically legitimate by both internal and external actors.

The first movers into a collapsed North Korea to establish stability and secure nuclear materials must be perceived as legitimate by both internal and external actors. Finding the balance between stability and the legitimacy of the actor(s) will be key. South Korea may consider itself as the most legitimate first mover to establish control in North Korea. China may focus on a longer timeline for intervening into North Korea and view a protracted, negotiated UN process as the only legitimate process.

A dispute over the legitimacy of the actor(s) securing stability in North Korea could block the immediate actions and cooperation needed to secure North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. This is a highly consequential question that must be discussed and sorted out before any instability occurs in North Korea. In a collapse scenario, rapid, effective, and short-term cooperation will be essential, since many response missions will be time sensitive. The longer WMDs are left unsecured, the higher the likelihood that they will go unaccounted for, cross international borders, and fall into the hands of state and non-state actors.

Predictable Counter Arguments

This proposed policy of public diplomacy will likely encounter criticism. Five anticipated points are listed below, followed by our response to these counter arguments.

First, individuals who seek an end-of-war declaration and those who advocate for engagement with the North Korean regime are likely to be critical of this recommended policy because they may perceive public diplomacy efforts to elicit retaliation from the North Korean regime and consequently be an obstacle to engaging with the Kim regime.

Second, there may be those who argue that North Korea should be accepted as a permanent nuclear weapons state and negotiate for limitations and reductions (similar to SALT/START negotiations).

Third, Beijing will presumably not support such efforts,as it will likely renew their longstanding claims that such efforts would constitute interference in the domestic affairs of another country. Furthermore, Beijing’s clear priority on preventing instability or conflict on China’s borders will likely foster its opposition to this U.S. policy.

Fourth, there may be an argument against providing information to North Koreans because it endangers North Korean citizens, given that the regime continues to severely penalize information crimes as political acts of treason.

Fifth, some may argue that public diplomacy with North Koreans may trigger unintended effects, causing some North Koreans to become further entrenched in their beliefs of the regime. If not maneuvered strategically and carefully, public diplomacy efforts could only harden the North Korean regime’s narrative and domestic legitimacy. Worse, the system could change just enough to create a veneer of progress that may convince some external actors that the regime is on the path towards reform. But if there is no momentum established in moving reforms towards a government that is more accountable to its people in a substantive way, we may end up with an even more sophisticated, legitimized Kim regime.

North Korea, in its dealings with other nations, has engaged in extensive public diplomacy campaigns for decades and continues to do so. The regime has invested in significant efforts to build sympathetic associations around the world, and to promote their values and messages to both targeted and general audiences and in various languages.34 North Korea’s efforts to shape both their domestic and foreign audiences’ views of the regime are becoming increasingly sophisticated on digital platforms, making our pursuit of this policy of U.S. public diplomacy that much more urgent.

These five counter arguments to a policy of public diplomacy are reasonable to address, but do not comprise sufficient reasons for blocking this policy from moving forward. Our responses to these five counterarguments are below. Some of our responses to separate counterarguments are the same.

It may be the case that public diplomacy could hamper short-term engagement with the North Korean government. However, the goal of any U.S. policy with North Korea has not been to merely de-escalate confrontation with the North Korean regime. A resolution of urgent crises does not equal, nor should be conflated with, meaningful and lasting peace.

Furthermore, pressuring the regime to change its behavior is not a new phenomenon, as most policies towards North Korea are designed to do exactly this. External pressure, in the form of sanctions and UN resolutions, is designed to compel the North Korean regime to change its behavior. This policy of public diplomacy would only widen the bandwidth of pressure into an area the regime is most vulnerable to: internal pressure. This will have the additive effect of convincing the regime to change their behavior.

Next, the United States and our allies must not accept North Korea as a permanent nuclear weapons state. Not only would this set a bad precedent for other states interested in pursuing a nuclear weapons program, and perhaps trigger an arms race in the region, but it would also convince Kim that his strategy is successful, causing him to double down on his efforts to continue using his nuclear program as his main bargaining chip in negotiations with states. Furthermore, even if the United States and our allies were to accept North Korea as a permanent nuclear weapons state, it is highly unlikely that North Korea would negotiate in good faith and act as a responsible owner of nuclear weapons. After all, the regime consistently claims domestically and internationally that the United States and ROK are its sworn enemies.

There are critical questions pertaining to U.S.-China relations vis-à-vis North Korea, such as 1) Will China have the same interests and preferred sequenced stages as the United States and neighboring states move towards peaceful denuclearization of the Korean peninsula? 2) To what extent can the United States rely on and coordinate with China regarding North Korean concerns? While it is beyond this report’s scope to address these critical questions, what can be affirmatively stated is that North Korea consistently serves as a spoiler for U.S.-China relations.

There are indeed significant risks involved for North Korean citizens who consume unauthorized information and media, which is why it is critical for entities who provide content to North Koreans to rigorously consider and adopt risk mitigation measures in every stage of planning and implementation for both content curation and information transmission efforts. For each intervention, there should be robust individual threat modeling based on knowledge of the regime’s evolving technical capabilities in surveillance, monitoring, and censorship of its citizens. Designing the methods through which information can be safely consumed is equally important as curating content that is nonpolitical for North Koreans to consume. If citizens are caught with foreign content, they are likely to face less harsh penalties if the content they are caught with is nonpolitical in nature.

Furthermore, there is a moral duty that entities living in free democracies must provide information to people living in totalitarian regimes who crave and desire information and media. It is an undeniable fact that North Koreans want to learn about the outside world. A female North Korean defector from North Hamgyoung Province who defected in 2013 said, “I knew South Korean and American movies were dangerous but I think my curiosity was greater [than my fear].”35 Various surveys and studies of North Korean escapees reveal that an overwhelming majority of escapees have had repeat exposure to foreign media inside North Korea despite the risks.36 Simply put, if North Koreans want information, entities in free societies ought to provide it. Coupled with this moral duty to provide information to people in unfree societies is the equally important duty to not manipulate anyone into viewing content that they do not desire to view or that would inadvertently endanger them.

To avoid unintended effects of public diplomacy efforts, it is critical to have as many North Korean escapees as possible involved in the process of curating and creating content, in the design of media devices and other information transmission methods, and in every part of the testing, iterating, and implementation phase. North Korean escapees are the best proxies for the target audiences for this policy of public diplomacy, and regularly gauging their feedback throughout the design, testing, implementation, and feedback process will minimize the possibility of unintended backfire effects.

Works Cited

Baek, Jieun. North Korea’s Hidden Revolution: How the Information Underground Is Transforming a Closed Society. Yale University Press, 2016.

Baik, Sung-Won. “Leaked N. Korean Document Shows Internal Policy Against Denuclearization.” Voice of America. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.voanews.com/east-asia/leaked-n-korean-document-shows-internal-policy-against-denuclearization.

Blinken, Antony. “Putting Human Rights at the Center of U.S. Foreign Policy.” United States Department of State (blog), February 24, 2021. https://www.state.gov/putting-human-rights-at-the-center-of-u-s-foreign-policy/.

“Blinken: N. Korea’s Human Rights Abuses Most Egregious in the World l KBS WORLD.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://world.kbs.co.kr/service/news_view.htm?lang=e&Seq_Code=160260.

Bowman, Bradley and David Maxwell. “Maximum Pressure 2.0: A Plan for North Korea.” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, December 2019. https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2019/12/3/maximum-pressure-2/.

Cha, Victor, and Lisa Collins. “The Markets: Private Economy and Capitalism in North Korea?” Beyond Parallel (CSIS), August 26, 2018. https://beyondparallel.csis.org/markets-private-economy-capitalism-north-korea/.

Chestnut, Sheena. “Illicit Activity and Proliferation: North Korean Smuggling Networks.” International Security 32, no. 1 (Summer 2007): 80–111.

Choe, Sang-Hun. “Kim Jong-Un Calls K-Pop a ‘Vicious Cancer.’” New York Times, June 11, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/11/world/asia/kim-jong-un-k-pop.html.

DuMond, Marie. “View Inside North Korea: Information and Its Consequences in North Korea.” Beyond Parallel (CSIS), January 12, 2017. https://beyondparallel.csis.org/information-and-its-consequences-in-north-korea/.

Fifield, Anna. “He Ran North Korea’s Secret Moneymaking Operation. Now He Lives in Virginia.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/he-ran-north-koreas-secret-money-making-operation-now-he-lives-in-virginia/2017/07/12/4cb9a590-6584-11e7-94ab-5b1f0ff459df_story.html.

Gauthier, Brandon. “North Korea’s American Allies: DPRK Public Diplomacy and the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, 1971-1976.” Wilson Center, January 2015. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/north-koreas-american-allies.

Hastings, Justin V., Daniel Wertz, and Andrew Yeo. “Market Activities & the Building Blocks of Civil Society in North Korea.” The National Committee on North Korea, 57.

Hotham, Oliver. “Inside the Kim Family Business - Office 39.” NK News, 2014. https://www.nknews.org/2014/07/inside-the-kim-family-business-office-39/.

Hotham, Oliver, and Colin Zwirko. “What’s Up Pyongyang? North Korea Experiments with Vlogging to Fight ‘Fake News.’” NK News, May 18, 2020. https://www.nknews.org/2020/05/whats-up-pyongyang-north-korea-experiments-with-vlogging-to-fight-fake-news/.

Indictment, United States of America v. Mun Chol Myong, 1:19-cr-00147-RC (D.D.C. filed March 22,

2021), page 7. (https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1379211/download)

Jacobsen, Annie. Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America. Little, Brown and Company, 2014.

Jang, Seulkee. “Exclusive: Daily NK Obtains Materials Explaining Specifics of New ‘Anti-Reactionary Thought’ Law.” Daily NK. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.dailynk.com/english/exclusive-daily-nk-obtains-materials-explaining-specifics-new-anti-reactionary-thought-law/.

Kretchun, Nat and Jane Kim. “A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment.” InterMedia, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e86bbf3c7360c384ada23c0/t/5e8756ad69bf073956519c68/1585927858207/A_Quiet_Opening_FINAL.pdf.

Lankov, Andrei, and Seok-hyang Kim. “North Korean Market Vendors: The Rise of Grassroots Capitalists in a Post-Stalinist Society.” Pacific Affairs 81, no. 1 (2008): 53–72.

“Mad Scientist Laboratory,” July 26, 2021. https://madsciblog.tradoc.army.mil/.

“NKorea Warns U.S. of ‘Very Grave Situation’ Over Biden Speech - ABC News.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/nkorea-warns-us-grave-situation-biden-speech-77443536.

Noland, Marcus, and Stephen Haggard. Witness to Transformation: Refugee Insights into North Korea. Petersen Institute for International Economics, 2011. https://www.piie.com/bookstore/witness-transformation-refugee-insights-north-korea.

“OHCHR | CoI DPRK Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/hrc/coidprk/pages/commissioninquiryonhrindprk.aspx.

Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Unification. “Policy on North Korean Defectors< Data & Statistics< South-North Relations< Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Unification.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/eng_unikorea/relations/statistics/defectors/.

“Pres. Bill Clinton Serves as Inaugural Speaker for Stephen W. Bosworth Memorial Lecture in Diplomacy.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMPGmn4yzHY.

“Reform and Open North Korea Is the Only Way for Economic Unification of Korean Peninsula.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://onekoreanetwork.com/2021/07/04/reform-and-open-north-korea-is-the-only-way-for-economic-unification-of-korean-peninsula/.

U.S. Department of Defense. “Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III and Secretary of State Antony Blinken Conduct Press Conference With Their Counterparts After a U.S.-ROK Foreign and Defense Ministerial (‘2+2’), Hosted by the ROK’s Foreign Minister Chung Eui-Yong and Minister of Defense Suh Wook.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/2541299/secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-and-secretary-of-state-antony-blinken-c/.

Smith, Josh. “North Korea Cracks Down on Foreign Media, Speaking Styles.” Reuters. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-media/north-korea-cracks-down-on-foreign-media-speaking-styles-idUSKBN29P0C4.

“The Creation of the North Korean Market System.” Daily NK, June 8, 2018. https://www.dailynk.com/english/report-creation-north-korean-market-system/.

“U.S. Department of State 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/north-korea/.

The White House. “U.S.-ROK Leaders’ Joint Statement,” May 22, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/05/21/u-s-rok-leaders-joint-statement/.

USC Center on Public Diplomacy. “What Is PD?” February 14, 2014. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/page/what-is-pd.

Whong, Eugene. “HRNK Releases Report on Human Rights Denial at the Local Level in North Korea.” Radio Free Asia. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/denied-from-the-start-12202018155602.html.

Williams, Martyn. “Digital Trenches: North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive.” The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, December 2019. https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/Williams_Digital_Trenches_Web_FINAL.pdf.

Wilson Center. “North Korean Public Diplomacy.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/collection/221/north-korean-public-diplomacy.

World Bank. “Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population) | World Bank Data.” Accessed July 27, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS.

Baek, Jieun. “A Policy of Public Diplomacy with North Korea.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, August 2021

- “NKorea Warns US of ‘Very Grave Situation’ Over Biden Speech - ABC News.”

- The definition and understanding of the term and methodology ‘public diplomacy’ has evolved over time. For this report, the author uses a widely accepted understanding of public diplomacy, which comprises activities intended to understand, inform, and influence foreign audiences. For a brief overview of the field of public diplomacy, see “What Is PD?”

- “Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III and Secretary of State Antony Blinken Conduct Press Conference With Their Counterparts After a U.S.-ROK Foreign and Defense Ministerial (‘2+2’), Hosted by the ROK’s Foreign Minister Chung Eui-Yong and Minister of Defense Suh Wook.”

- “Blinken: N. Korea’s Human Rights Abuses Most Egregious in the World l KBS WORLD.”7,27]]}}}],”schema”:”https://github.com/citation-style-language/schema/raw/master/csl-citation.json”}

- For more information on North Korea’s human rights record, see “OHCHR | CoI DPRK Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” and “US Department of State 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.”

- Whong, “HRNK Releases Report on Human Rights Denial at the Local Level in North Korea.”

- “Reform and Open North Korea Is the Only Way for Economic Unification of Korean Peninsula.” Fifield, “He Ran North Korea’s Secret Moneymaking Operation. Now He Lives in Virginia.” [video interview included in this article] Ri Jong-Ho held senior level positions in Office 39, which the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) refers to as “a secretive branch of the government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) that provides critical support to North Korean leadership in part through engaging in illicit economic activities and managing slush funds and generating revenues for the leadership.” “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. Mun Chol Myong.” For more on Bureau 39, see Chestnut, Sheena, “Illicit Activity and Proliferation: North Korean Smuggling Networks” and Hotham, “Inside the Kim Family Business.”

- Baik, “Leaked N. Korean Document Shows Internal Policy Against Denuclearization.”

- “OHCHR | CoI DPRK Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” 11.

- There are historical precedents of the USG pursuing human rights and security priorities in parallel. For example, President Reagan and his administration’s arms control negotiations with the Soviet Union also focused on the Soviet Union’s human rights record. This case is one of several strong historical precedents that underscore the belief that human rights and denuclearization do not have to be mutually exclusive pursuits, but rather could be parallel policy priorities.

- “OHCHR | CoI DPRK Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” 109.

- For a summarized analysis of North Korea’s laws and practices of penalizing crimes related to information, see Williams, “Digital Trenches: North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive.”

- North Korea’s recently introduced ‘anti-reactionary thought’ law has stricter prohibitions and more severe penalties for consuming and circulating foreign content. Jang, “Exclusive: Daily NK Obtains Materials Explaining Specifics of New ‘Anti-Reactionary Thought’ Law” and Smith, “North Korea Cracks down on Foreign Media, Speaking Styles.”

- “NKorea Warns US of ‘very Grave Situation’ over Biden Speech.”

- Nat Kretchun and Jane Kim, “A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment,” 1.

- There are several such USG-sponsored innovation programs. An example of a program that seeks to develop innovative capabilities for various operations and contexts is the U.S. Army’s “Mad Scientist” program, “Mad Scientist Laboratory.”

- Author gained these insights from off-the-record conversations between 2018-2021.

- For more on how foreign content and media has affected North Korean people, see Baek, North Korea’s Hidden Revolution: How the Information Underground Is Transforming a Closed Society, and Nat Kretchun and Jane Kim, “A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment.”

- Nat Kretchun and Jane Kim, “A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment,” 8.

- Choe, “Kim Jong-Un Calls K-Pop a ‘Vicious Cancer.’”

- This categorization of the North Korean population is borrowed from Maxwell and Bowman, “Maximum Pressure 2.0: A Plan for North Korea.”

- For more on socioeconomic changes in the aftermath of the Arduous March of the 1990s, see Noland and Haggard, Witness to Transformation.

- For more on the marketization of North Korea, see “The Creation of the North Korean Market System.” (downloadable report at the bottom of this article), Hastings, Wertz, and Yeo, “Market Activities & the Building Blocks of Civil Society in North Korea”, Cha and Collins, “The Markets: Private Economy and Capitalism in North Korea?” and Lankov and Kim, “North Korean Market Vendors.”

- See “Maximum Pressure 2.0” page 59 for a similar idea on creating an entity (Korea Defector Information Institute) through which North Korean escapees could provide information.

- There are an estimated 33,783 North Korean escapees in South Korea, nearly 250 in United States, an estimated 1,000 in the United Kingdom, and several thousand living in Canada, Australia, and Europe. “Policy on North Korean Defectors< Data & Statistics< South-North Relations< Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Unification.”

- There are moral hazards associated with foreign radio programs. One often cited case is the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. While the role that Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty played in motivating the anti-Soviet protests in Budapest remains disputed, it was the case that there was no Western intervention to support the protests in Hungary during the Soviet crackdown of the protests.

- Blinken, “Putting Human Rights at the Center of U.S. Foreign Policy.”

- “U.S.-ROK Leaders’ Joint Statement.”

- “Pres. Bill Clinton Serves as Inaugural Speaker for Stephen W. Bosworth Memorial Lecture in Diplomacy - YouTube.” (Minute 32:30)

- “Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population) | World Bank Data.”

- This table uses Bradley Bowman and David Maxwell’s conception of audience segmentation of North Koreans; Maximum Pressure 2.0

- Maximum Pressure 2.0, page 48

- Dr. Kurt Campbell, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs—Asia Pacific (DASD-ISA-APAC), remarks to USFK planners during a briefing at the Pentagon, 1 May 1998.

- Gauthier, “North Korea’s American Allies: DPRK Public Diplomacy and the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, 1971-1976.”, “North Korean Public Diplomacy.” Hotham and Zwirko, “What’s Up Pyongyang? North Korea Experiments with Vlogging to Fight ‘Fake News.’”

- Nat Kretchun and Jane Kim, “A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment,” 26.

- In a 2015 BBG survey of 250 North Korean refugees, 81% had viewed foreign content on USBs in North Korea. Kretchun, 19.

- 91.6% of North Korean respondents to this CSIS study stated that they consumed foreign media at least once a month. DuMond, “View Inside North Korea: Information and Its Consequences in North Korea.”