The unbridled ambitions of the neo-conservatives and assertive nationalists in President George W Bush's first administration produced a foreign policy that was like a car with an accelerator, but no brakes. It was bound to go off the road. But how should America use its unprecedented power, and what role should values play? Realists warn against letting values determine policy, but democracy and human rights have been an inherent part of American foreign policy for two centuries. The Democratic Party could solve this problem by adopting the suggestion of Robert Wright and others that it pursue progressive realism. What would go into a progressive realist foreign policy?

It would start with an understanding of the strength and limits of American power. The US is the only superpower, but preponderance is not empire or hegemony. America can influence but not control other parts of the world.

Power always depends upon context, and the context of world politics today is like a three-dimensional chess game. The top board of military power is unipolar; but on the middle board of economic relations, the world is multipolar, and on the bottom board of transnational relations comprising issues like climate change, illegal drugs, avian flu and terrorism, power is chaotically distributed.

Military power is a small part of the solution in responding to these new threats on the bottom board of international relations. They require cooperation among governments and international institutions. Even on the top board (where America represents nearly half of world defence expenditures), the military is supreme in the global commons of air, sea and space, but more limited in its ability to control nationalistic populations in occupied areas.

A progressive realist policy would also stress the importance of developing an integrated grand strategy that combines hard military power with soft attractive power into smart power of the sort that won the Cold War. America needs to use hard power against terrorists, but it cannot hope to win the struggle against terrorism unless it gains the hearts and minds of moderates. The misuse of hard power (as at Abu Ghraib or Haditha) produces new terrorist recruits.

Today, the US has no such integrated strategy for combining hard and soft power. Many official instruments of soft power — public diplomacy, broadcasting, exchange programmes, development assistance, disaster relief, military to military contacts — are scattered around the government, and there is no overarching strategy policy, much less of a common budget, that even tries to integrate and combine them with hard power into a national coherent security strategy.

The US spends about roughly 500 times more on the its military than it does on broadcasting and exchanges. Is this the right proportion?

And how should the government relate to the non-official generators of soft power — everything from Hollywood to Harvard to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation — that emanates from civil society?

A progressive realist policy must advance the promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness enshrined in American tradition. Such a grand strategy would have four key pillars: (1) providing security for the US and its allies; (2) maintaining a strong domestic and international economy; (3) avoiding environmental disasters (such as pandemics and global flooding); and (4) encouraging liberal democracy and human rights at home and, where feasible, abroad.

This does not mean imposing American values by force. Democracy promotion is better accomplished by attraction than coercion, and it takes time and patience.

The US would be wise to encourage the gradual evolution of democracy, but in a manner that accepts the reality of cultural diversity.

Such a grand strategy would focus on four major threats. Probably the greatest danger is the intersection of terrorism with nuclear materials. Preventing this requires policies to counter terrorism and promote non-proliferation, better protection of nuclear materials, stability in the Middle East, as well as greater attention to failed states.

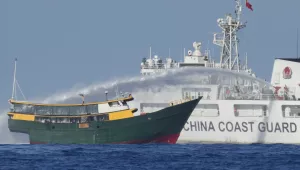

The second major challenge is the rise of a hostile hegemony as Asia gradually regains the three-fifths share of the world economy that gradually comes to match its three-fifths share of the world's population.

This requires a policy that integrates China as a responsible global stakeholder, but hedges against possible hostility by maintaining close relations with Japan, India and other countries in the region.

The third major threat is an economic depression, that could be possibly triggered by financial mismanagement, or by a crisis that disrupts global access to oil flows from the Persian Gulf, where two-thirds of global world oil reserves are located.

This will require policies that gradually reduce dependence on oil, while realising that the American economy cannot be isolated from global energy markets.

The fourth major threat is ecological breakdowns, such as pandemics and negative climate change. This will require prudent energy policies as well as greater cooperation through international institutions such as the World Health Organisation.

A progressive realist policy should look to the long-term evolution of world order and realise the responsibility of the most powerful country in the international system to produce global public or common goods.

In the 19th century, Britain defined its national interest broadly to include promoting freedom of the seas, an open international economy, and a stable European balance of power. Such common goods helped Britain, and benefited other countries as well. They also contributed to Britain's legitimacy and soft power.

With the US now in Britain's place, it should play a similar role by similarly promoting an open international economy and commons (seas, space, internet), mediating international disputes before they escalate, and developing international rules and institutions. Because globalisation will spread technical capabilities, and information technology will allow broader participation in global communications, American preponderance will become less dominant later this century.

Progressive realism requires America to prepare for that future by defining its national interest in a way that benefits all.

Joseph Nye is university distinguished service professor at Harvard and Sultan of Oman professor of international relations at the Kennedy School.

Nye, Joseph. “Progressive Realism.” The Bangkok Post, August 25, 2006