Introduction

No piece of hardware better exemplifies America’s military might than an aircraft carrier. And for more than seven decades, dating to the brutal naval clashes of World War II, that has been especially true in the Asia-Pacific. Broad oceanic expanses, narrow straits through tropical archipelagos, and ever-expanding maritime trade make naval power the guarantor of security in the region. U.S. aircraft carriers remain the lynchpin of that power.

So when I landed aboard the USS John C. Stennis as it sailed through the waters of the South China Sea in April 2016, I knew the gesture would be noticed. The nuclear-powered Stennis is massive: longer than three football fields, the Nimitz-class carrier is essentially a 4.5-acre floating fortress home to 3,000 American men and women who do everything from conduct counter-piracy operations to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Even before we touched down on the flight deck, the Chinese foreign ministry had issued a statement criticizing my visit as emblematic of a “Cold War mentality.”1

China’s reaction stemmed in part from the Stennis’ location: she was patrolling in the 500-mile stretch of open ocean between Manilla and the Paracel Islands. The Paracels, less than five square miles of coral reef and sand that dot the ocean between the Philippines and China’s Hainan Island, typify a series of nondescript but strategically located tropical island chains that had become major irritants in international relations. Both China and Vietnam claim the Paracels as their own. Both had taken unilateral actions in the area to bolster their claims. Unchecked, friction over the Paracels, or over the disputed Spratly Islands to the south, risked jeopardizing decades of security and prosperity in Asia.

The New York Times reported that the visit would play into “fears within the Chinese leadership about American efforts to halt China’s rise.”2 China’s overheated reaction suggested its leaders had either misinterpreted the visit or, more likely, sought to mischaracterize it. My visit was not about Cold War muscle-flexing. But it was important to challenge China on an essential principle of international law—the freedom to navigate in international waters—and to underline America’s enduring commitment to peace and stability in the region.

The cornerstone of America’s defense is deterrence. From Guam and Hawaii to Yongsan and Yokosuka, the nearly 400,000 civilian and military personnel of our Pacific Command are dedicated first and foremost to the defense of U.S. interests and allies. That’s the acid test for our presence in the Asia-Pacific. But they also have a politico-military role, which is to undergird generally friendly economic and political relationships and cooperative relationships among militaries. China, however, sees this long-standing mission and the future of the region very differently. And its behavior is increasingly hostile to the requirements of a secure, prosperous region. China’s rise is one of the great miracles of our time. My hope is that it helps lift living standards even more broadly across the Pacific. But I believe that China’s behavior is instead driven by a needless struggle for supremacy that threatens a long and dearly bought peace in the Pacficic that dates from 1945.

My visit to the Stennis concluded without further escalation, though Beijing said it proved “who was the real promoter of the militarization in the South China Sea.” The truth, as I and many other U.S. officials said repeatedly, is that the United States had no objection to China’s rise. What the U.S. should not accept, and should strenuously work against, is the growing Chinese tendency to undermine the pillars of peace and stability that have enabled its rise and that of its Asian neighbors.

I have long observed two competing strains in Chinese strategic thinking. One values partnership and increased integration in global security structures. The other leans toward unilateral action and refuses to acknowledge global norms when they are seen to inhibit China’s interests. During my time as Secretary, and in fact throughout nearly 25 years of familiarity with Chinese military leadership and presidents Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping, I became concerned that this second strain was growing ascendant among China’s leaders. Our goal was, and should continue to be, not to impose Cold War, NATO-inspired structures on the Asia-Pacific or on our relationship with China, but to invite China into a far different, but equally successful, multilateral security network.

My tenure as Secretary left me firmly convinced of the importance of this goal—and painfully aware of the challenges in achieving it. Since World War II, our policy toward the Asia-Pacific, and toward China in particular, has enjoyed remarkable continuity. But it was conceived in an age when China was an extremely poor nation—one that had withstood a “century of humiliation” at the hands of Western powers. Today, China is a colossus, with an economy that rivals ours and rapidly expanding military capabilities. Redefining America’s strategic posture for Asia to reflect these 21st century realities became one of my most important jobs. My recalcitrant counterparts in Beijing—and some of my occasionally short-sighted colleagues in Washington—ensured it would be one of my most difficult.

The Strategy of a Principled, Inclusive Network

To understand how I approached China during my time as Secretary, it’s important to note that I don’t see U.S. strategy in Asia as centered on China at all. I said many times: We don’t have a China policy, we have an Asia policy. The heart of that policy is a mesh of political, diplomatic, economic, and military relationships with many nations that has sustained security and underwritten an extraordinary leap in economic development.

During my time as Secretary, I referred to this structure over and over as the “principled, inclusive network.” Enunciating and reinforcing its strategic and military dimensions in a rapidly changing security environment was my constant priority as Secretary of Defense. Even amid pressing challenges such as the fight against ISIS and the need to confront Russian aggression, no other issue I dealt with had such lasting implications for our national security and prosperity.

My three-word title for this policy was admittedly not very catchy. But my counterparts in the region understood it. They understood that all three words have been essential to its success and will remain essential to its future.

It is based, first and foremost, on fundamental shared principles of international behavior: on peaceful resolution of conflict and opposition to coercion; on freedom of commerce, including freedom of navigation through international space by sea and air; on a shared responsibility among the network’s participants for preserving security and stability. It also refers to the principles of free and fair trade—principles embodied (albeit imperfectly) in the now-abandoned Trans-Pacific Partnership. These principles, not geographic or ideological lines as in Cold War Europe, define the structure. A European system would not work in Asia. Adherence to these principles may on occasion work against any nation’s short-term interests on individual issues, including our own. But in the long run, participants will be safer and more prosperous for their commitment to its principles. They are principles that have served the Asia-Pacific well over the past seven decades. More and more countries have come to embrace them as they see the dividends that result: first Japan and Taiwan, then South Korea, then Southeast Asia, and now India. Principle stands in contrast to the coercive, statist and zero-sum behavior in which China excels.

Next, in addition to being principled, the network is also inclusive. It seeks to grow in ways that accommodate each of its members’ growth. It is a remarkable feature of the U.S.-led security architecture of the post-World War II Asia-Pacific region that it has continually broadened. More nations have participated, and participated more deeply, at every stage of its development. Some participants, such as Australia, have long cultural and political ties to the United States. Others, such as Vietnam, are one-time adversaries who have made a strategic choice to join. Still others, such as India, have gradually strengthened their engagement as their economic and security challenges have changed. I stressed the word “inclusive” in this policy formulation in part to signal that China was a welcome member.

Third and finally, it was important to see these relationships as an informal network—not an alliance, not a treaty, not a bloc. Nor did they comprise a strategy of condominium, in which superpowers China and the United States dealt over the heads of other Asian powers.

The network structure suits Asia. Unlike NATO, it was not formed by a formal compact of nations joined in collective defense against a single foe. Nor is it, as the Trump administration (or at least the president himself) apparently sees the region, just a series of one-on-one relationships between individual nations. Such an erroneous strategic approach would fritter away one of America’s key advantages over China, the interlocking relationships we’ve built over decades. It would allow China to do what it does best: marshal its combined economic, political, and military muscle that only a statist dictatorship can wield against smaller nations, picking them off and their businesses one-by-one. The network as I meant it is a multi-layered complex of relationships, some bilateral, some multilateral, that can accommodate a wide variety of interests within a shared regional understanding of fundamentals.

Neither a NATO-style alliance nor one-by-one relationships allow us to forge that kind of progress, but a flexible, adaptable network based on principles and inclusiveness can. It is not about one country—not about China, and not about the United States. It is about a set of shared principles that have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in empowering Asia, the most consequential region for America’s future, to achieve remarkable economic and social progress. Preserving and strengthening that network should, I believe, be the overarching strategic objective of U.S. security policy in Asia.

I always noted that despite Chinese propaganda, the network actively seeks China’s participation, as our military-to-military engagements and those of other Asian nations have demonstrated. While China would love nothing more than to convince its neighbors that American policy in the region is driven by a desire to exclude it, the network is built on respect for any partner who adheres to its principles. After benefitting from the network since the days of Deng Xiaoping, one would think it’s time for China to contribute to it.

Sadly, this was not at all China’s policy during my time as Secretary of Defense or during the years leading up to them. Nor since.

Aligning Economic and Military Strategy

China never misses the chance to describe its growing power as a “peaceful rise.” Though serious observers don’t buy the spin, one reason Beijing can make such a claim is that Washington since the end of the Cold War has often backed down in the face of Chinese bullying. From aggressive territorial claims to human rights abuses and brazen theft on a trillion-dollar scale, China has violated core international norms time and again with little repercussions beyond scolding American speeches. The rationale for tolerating China’s troubling behavior in the security sphere was premised on an economic policy that never made sense to me. The de facto economic relationship we have with China is that we give up skilled jobs here in exchange for cheap goods made there that we buy with money borrowed from China. Some see that as virtuous. I don’t. Strategic issues of trade are not outside the lane of the Secretary of Defense, since they clearly have security implications. The Trans-Pacific Partnership, a U.S.-led trade bloc negotiated by the Obama administration’s economic team, was the most obvious example—by rejecting it, the United States has pushed our Asian friends and allies into the arms of China’s state-run economy, giving Beijing even greater leverage to impose its will. China’s centralized control of its economy gives it tools that simply aren’t possible in our society. American economists have yet to give us a credible policy playbook for dealing with a country which, for example, will threaten to stop buying important South Korean agricultural goods if South Korea agrees to deploy missile defenses against North Korean missiles. More broadly, I think our passive approach has been just plain bad for the American people. Our economic policies tend to treat China as a big version of France—rather than a Communist monolith. In all the decades of the Cold War, we never had a substantial trading relationship with a communist nation. We have no trade playbook for China—and it shows. The Trump administration’s tariff measures in April 2018 are a predictable over-correction to this problem. It’s important to transform these policies, to protect our security and our prosperity.

In April 2015, I gave a speech on Asia Policy at Arizona State University’s McCain Institute before a trip to Singapore and Vietnam. There, I spoke about the need for economic and diplomatic strategy that married America’s strengths in these realms to our military might. In particular, I advocated for the TPP. Perhaps no other facet of the Pacific rebalance demonstrated the potential and the frustrations of Asia policy during my time as Secretary.

The TPP’s economic rationale was obvious: it would have opened more Asian markets to U.S. goods, strengthened protections for U.S. companies’ intellectual property, and reinforced environmental and labor protections, leveling the playing field for U.S. firms in those areas while benefitting the people of the region. But it was the security aspects of the TPP that naturally interested me most. By strengthening our relationships with key regional partners, the TPP would bolster the network and, with it, our national security. For that reason, I often said that the TPP was as important strategically as an aircraft carrier.

That wasn’t to be; Congress abandoned the TPP after the 2016 election. Could a different, more effective political strategy have achieved its ratification, or was its defeat inevitable? We’ll never know. The domestic politics of trade were stacked against the deal. The top four vote-getters in the 2016 election cycle—Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, Donald Trump, and Ted Cruz—all opposed it.. The TPP’s defeat wasn’t just a missed opportunity. It provided space for China to expand its already significant economic influence over key Asian economies—influence it is unlikely to wield in as open and respectful a manner as the United States has done. It was a missed opportunity to strengthen our strategic relationships in Asia by helping our friends and allies in the region counter the enormous economic leverage China has over them—leverage it is increasingly willing to use to bend the region to its will in the security realm. I meant it when I said I would rather have TPP than another carrier to deploy to the Pacific. Our failure to finalize participation in the agreement damaged our national security in the region that much.

The Up-and-Down Nature of U.S.-China Relations

Though some journalists accurately called me one of the few “China hawks” in the Obama administration, the irony of my time as Secretary of Defense is that I would have much preferred to lead the department toward a stronger and more productive relationship with China and its military. Much of my time in and out of government has been spent trying to build those stronger ties. I know and consider as friends dozens of senior Chinese government and military officials, and I’ve visited there many times. But China’s behavior over the years no longer warranted that approach, especially from a Secretary of Defense.

I’ve done my part to try to contribute to closer U.S.-China relations. I helped lead a series of meetings from 1998 to 2008 with senior Chinese military delegations, almost one a year, as part of the Harvard-Stanford Preventive Defense Project, which I co-directed with one of my predecessors as Secretary, William Perry. Those efforts also included meetings with Taiwanese officials in close parallel, as well as meetings with other Asian nations. Additionally, in 1998, when President Clinton named Perry the coordinator for North Korea policy, I served as his deputy, which entailed regular meetings with Chinese leaders. Going over agendas from those meetings a decade or more ago, I am struck by the breadth of the discussions—everything from cooperation on nuclear nonproliferation issues to the shared importance of solar energy development and other environmental matters. The discussions were generally friendly but frank. Often in China, our official host was Xiong Guankai, a general who headed foreign relations for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Xiong could be hawkish and harsh in tone, definitely among the most aggressive Chinese officers of that period. Today, he’d fit well within the PLA mainstream. Despite the occasional tough talk, I consider him a friend. But I’m realistic about the frame of mind Xiong reflects.

During the first year of the Bush administration, it took a hard line on China in the brief period before 9/11 swallowed its attention. During that period, I got regular phone calls from China’s defense attaché, desperate for suggestions as to how to arrange a meeting with then Secretary of Defense Don Rumsfeld or his senior staff. The Bush administration had intended for its first Quadrennial Defense Review, published in late 2001, to focus strongly on countering China, a focus that I thought if taken too far would reinforce the arguments of many Chinese officials that we saw China as an enemy and give more impetus to their steady movement toward truculence. But it turned out that the Bush administration ended up with little time and attention to spend on the Asia-Pacific compared to the Middle East, and during the same period Chinese attitudes evolved in troubling directions nonetheless.

I mention these relationships between myself (and other U.S. leaders) and Chinese figures during the years before the Obama administration because they illustrate a path that U.S.-China security relationships could have taken—one in which China and the United States would surely disagree with one another, but at least operate by the same set of rules, and in relationships of trust and basic understanding. China, on this path, would be an increasingly important pillar in the principled and inclusive security network.

This long experience had convinced me that the United States should reject the view that China is an adversary that must be contained. This view holds that a rising power like China encountering an established power such as the United States often leads to conflict. It’s an idea as old as the ancient Greeks and the story of a dominant Sparta and rising Athens, which inspired the popular term for such conflicts: the “Thucydides Trap.” Thucydides, a historian of the period, wrote that this dynamic caused the Peloponnesian War. I have used Thucydides’ analysis in the course on military history I gave at Harvard in years past, and my friend Graham Allison subsequently wrote an important book on the subject.

The analogy can be a useful one, and it captures some aspects of the challenge we face today with China. As a form of applied history, it’s a relevant warning against reacting without careful thought to the rise of a new power. But in the popular retelling of Thucydides, it was irrational Spartan fear of Athens’ peaceful, nonthreatening rise that provoked the Peloponnesian War. That tale inaccurately portrays the ancient story—in which Athens’ own miscalculations certainly played a role—and it badly mischaracterizes the U.S.-China relationship. We are not a fearful Sparta and China is not a young and innocent Athens. The United States has welcomed China’s inclusion in global economic and security structures for 50 years and should continue to do so—so long as it does not undermine the pillars that have made those structures so successful. Rather than lashing out in fear, the United States has on the contrary behaved in ways that encouraged China to succeed and join the family of nations as a full and active partner since the days of Deng Xiaoping. It’s also worth reminding those, especially in China, who seek to apply Thucydides to the present that war did in fact come to Athens and Sparta—and that Athens, China in this famous analogy, lost the war.

But neither of our nations is doomed to relive history. There is another, far more fruitful path, and I believe there is still an opportunity to follow it.

Chinese leaders prefer to be convinced that we see them as a hostile power, and that our real strategy is containment. Not only is that untrue; it would be unwise. China is not the Soviet Union, and Asia today is not Europe in the post-war period. Unlike the USSR, which wanted to make a communist world, China has no such stated intention. Despite its sometimes heated rhetoric, Beijing has a strong interest in preserving the institutions and security structure that have enabled its rise, while ensuring that its own internal governance is largely unchallenged. The Warsaw Pact existed to oppose the Western democracies’ post-war vision of European security. Far from impeding it, the U.S.-led post-war security architecture in the Pacific has unquestionably fueled China’s revitalization. But while some Chinese officials still grudgingly acknowledge this fact, the dictatorship’s internal propaganda ignores it entirely.

The best way to counter such propaganda is with persistent, persuasive action. And though Beijing won’t acknowledge it, the U.S. effort to integrate China more closely with Asia’s security network has yielded some significant successes in that realm. China has sent warships to the Gulf of Aden to aid in international anti-piracy efforts since 2008. This was remarkable, because since the 1949 establishment of Communist China, its military has never strayed far from the mainland (though it fought a number of wars around its borders). Similarly, U.S. and Chinese officials have made important and substantive progress on measures to reduce the risk of miscalculation when our forces operate in close proximity at sea or in the air, part of a broader military-to-military engagement effort. In 2015, during my time as Secretary, we reached an agreement with China on safety in air-to-air engagements involving our forces. Similarly, after years of resistance, China in 2014 joined the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea agreement, to prevent potential maritime accidents. These are significant changes from what had been a more isolationist stance that left China out of most military-to-military contacts until recent years. Today, Chinese forces even participate in the region’s biggest multilateral military exercise, the annual Rim of the Pacific Exercise, or RIMPAC, hosted by the United States and based at Pearl Harbor. I remember the longstanding reluctance of the PLA Navy to join RIMPAC, and it did not do so until 2014.

I continued to invite China to RIMPAC during my time as Secretary, despite significant pressure from members of Congress such as John McCain to disinvite them. That was exactly the wrong thing to do. It was contrary to the inclusive approach to Asia strategy I advocated. International agreements and military exercises are important to build fundamental understanding between our militaries that helps avoid miscalculation in time of crisis. And the more we can bring China into the international fold, the less likely the Chinese are to engage in go-it-alone behavior.

More pointedly, if China was to be excluded from military affairs in the region, it should be their doing, not America’s. Self-isolation by China itself has been, in fact, a steadily growing tendency.

China’s Self-Isolation

There is no question that the principled, inclusive security network in the Asia-Pacific would be stronger if China participated. So would China. After all, no nation has benefitted more from its peace dividend. And that is why I spent decades, long before Chinese media portrayed me as a Cold War holdover, seeking to strengthen the U.S.-China security relationship.

But policy needs to be based on what the Chinese do think, not what they should think. As I’ve said, China exhibits two tendencies in its international behavior: One is productive and engaging, participating in and strengthening multilateral institutions. The second and growing strain is bullying and rule-breaking, coercive and domineering. Just as there are two strains in China’s behavior, I have come to believe that there need to be two branches of our policy toward China. When China engages productively with the international community, we should seek to encourage and reinforce this tendency. But when China behaves inappropriately on the international stage, the United States must firmly push back and stand up for the principles of international order. At times, U.S. policy has not pushed back as firmly as necessary to discourage China’s growing strain of bullying behavior.

Maritime and cyber activities are two forms of Chinese aggression that cause concern in the states of the Pacific network, which deepens China’s self-isolation. China’s actions in the South China Sea are a direct challenge to peace and stability in the Pacific. Unjustified claims in the Spratlys and Paracels are bad enough, but efforts to make these claims a fait accompli by artificially enlarging reefs and atolls, building airstrips and fortifications and installing radar and other military systems are a direct challenge to international norms. As I said repeatedly during my time as Secretary and as the State Department and White House repeated as well, the United States took no position on the substance of these claims, nor on the other, equally expansive claims that other Asian nations have made in the South and East China seas. We are not for or against any particular claim; what we oppose is the attempt to resolve these claims by figuratively, and sometimes literally, bulldozing through international law, taking unilateral action, and threatening to resolve claims by force.

The so-called “Nine-Dash Line” exemplifies China’s expansive and coercive territorial claims. China has regularly published maps containing a nine-dashed line encompassing all of the South China Sea as evidence of its “indisputable sovereignty” over the waters and islands of the area.3 There is no plausible legal or historical basis for such a claim, but China persists in making it—hoping that it can bully its neighbors into accepting it and convince the United States not to care. There’s a children’s book called “Harold and the Purple Crayon,” in which a four-year-old can reshape the world exactly as he wants it by simply drawing with his purple Crayon. The Nine-Dash Line is just like Harold’s make-believe.

Even as China became more audacious in projecting its power in the region, some mistaken policy mechanisms in Washington hindered our ability to counter it. I was frustrated as Secretary by our inability to promote freedom of navigation, an essential principle of the Asia-Pacific security network. Free use of the seas and air fueled the engine of Asian economic growth by enabling trade across the vast distances and through the narrow waterways of the region. One important way the United States upholds this principle is through freedom of navigation operations, or FONOPs.

FONOPs challenge excessive maritime and airspace claims and reinforce the rights of the United States and any other nation to fly, sail, and operate anywhere international law allows. Such operations are a routine feature of our naval activity; in fiscal 2015, the United States conducted FONOPs challenging unjustified claims by 22 nations, including adversaries such as Iran and close allies such as Japan and South Korea. But operations involving China were the only ones to make headlines.

Unfortunately, National Security Council approval for FONOPs, which have been required since 2002, are far too difficult to obtain. In fact, White House and NSC involvement in the details of planning FONOPs was itself unusual. The NSC approached the question in a lawyerly manner that I thought badly missed the strategic forest for the legal trees. When we did receive approval, the diplomatic and political messaging surrounding operations was timid and ineffective. FONOPs merely declare that, whatever any nation does to try to create “facts on the water” by making expansive claims or undertaking hurried construction projects, those efforts will not be allowed to interfere with the rights of other nations to peacefully transit international waters. FONOPs say, “The principle stands, no matter how hard you try to dredge your way out of it.” Yet the United States seldom spoke with that clarity.

This failure rested in part on an arcane legal distinction. Under international maritime law, all vessels, including warships, are entitled to what is known as “innocent passage” through another nation’s territorial waters, so long as they do not engage in military activities such as firing weapons. Conducting a transit near an island claimed by China as an innocent passage was the least confrontational FONOP we could undertake. For example, in November 2015, the USS Lassen passed within the 12-nautical-mile territorial limit of Subi Reef, a bare spec of sand in the South China Sea, naturally under water at high tide, where China had dredged up enough soil to build an artificial reef large enough for an airstrip and was claiming territorial rights. The Lassen’s trip took months of meetings and planning to arrange, but in an arcane provision of international law having to do with Subi Reef’s location near another land feature, the ever-myopic NSC lawyers ultimately required the ship to observe the rules of innocent passage, rather than conducting full operations during the transit as we originally planned. When news of the innocent passage became public, we were widely criticized for failing to forcefully confront China’s excessive claims; some observers even argued that by observing innocent-passage rules, we had implicitly sanctioned China’s territorial claims.4 That was not the case, but I fear the accusation that we muddled our message is justified. The Chinese spun former U.S. officials, journalists, and think tanks with glee. It would have been better to have switched to a less ambiguous FONOP when it became clear that the message of the Subi Reef transit plan would become so garbled.

The South China Sea gets most of the attention from security professionals, but perhaps even more destabilizing in the long term are China’s actions in cyberspace. The Internet and rapidly advancing computer power have played a central role in building prosperity worldwide, and no nation has benefitted more than China. Yet China has repeatedly taken actions in cyberspace that put short-term security or economic interests ahead of long-term benefit for China and the rest of the world. Not long after I became Secretary of Defense, Washington discovered China’s massive theft of personal data on millions of federal employees from the Office of Personnel Management. More broadly, China has sought to quash the free flow of ideas—establishing its “Great Firewall” to prevent internal dissent and working through international institutions to ensure that it and other authoritarian nations can throttle ideas. China threatens to expel U.S. tech companies that refuse to abet its repression, and it regularly engages in economic espionage against U.S. companies.

Attempts to engage the Chinese on these issues are generally met by protests that the United States is infringing on China’s “core interests”—inflexible positions not subject to negotiation or compromise. Trying to extend the use of this phrase from control of Tibet or Taiwan to the South China Sea, China has used “core interest” as a trump card to shut down discussion. But as I have occasionally told Chinese officials, China can’t just play the “core interests” card and expect the United States to endorse claims and demands that threaten the principled, inclusive network. And this is why, despite my strong desire for closer and more productive ties with China, my time as Secretary of Defense tilted toward confrontation rather than cooperation with the Chinese.

Serving under Bill Perry in 1996, I had seen a vivid demonstration of the need for strong push-back against China’s unproductive tendencies. In March of that year, as Taiwan prepared to hold its first democratic presidential election, China conducted a series of provocative missile launches within 20 miles of Taiwan’s coast, and was preparing to hold massive live-fire exercises along the Taiwan Strait. There was a real fear of military confrontation between the mainland and Taiwan. But then Bill Clinton called China’s bluff. In what China called a “brazen” display of U.S. military might, Washington sent two carrier groups to the region. China backed down, Taiwan’s election went ahead, and U.S.-Taiwan relations grew stronger. Shortly afterward, the Chinese defense minister came to the Pentagon and stated ruefully that he had “lost face” in the encounter. Then-Secretary of Defense Perry replied simply, “You deserved to.” China’s leadership clearly took the lesson to heart: its military investments since then seem designed in part to deter us from providing that kind of protection to our friends in need.

I greatly admired President Obama’s cool, analytic personality. It often served him well. I fear that China, and the South China Sea in particular, may have been one area in which the president’s analysis misled him. He believed that traditional Washington foreign policy thinkers were prone to reach for confrontation and containment as strategies when a less forceful approach was called for. So he viewed recommendations from me and others to more aggressively challenge China’s excessive maritime claims and other counterproductive behaviors as suspect. When I would travel to Asia, his direction to me was succinct: “Don’t go banging pots and pans over there.” I was not to make trouble.

There were few other voices in the administration advocating a tougher approach. Hillary Clinton had left by the time I was Secretary, replaced at State by John Kerry, who had plenty of acquaintance with the Asia-Pacific region, but whose efforts were focused on the Middle East, especially the Iran nuclear deal and on Syria. His priorities for Asia were TPP and the climate change agreement, a major success. Economic policy-makers such as Jack Lew at Treasury, like his predecessors going back to the Bush administration, mostly wanted to avoid turbulence in the financial markets. Vice President Biden was closest to my own way of thinking—especially on the economic aspects of our relationship with China.

I was especially concerned by the implications of China’s successful attempts to convince the president to endorse what it called “a new model of superpower relations” in the Pacific. In China’s view, Asia over the past 70 years was dominated by one superpower—the United States—and now it was time for the United States to step back and let China exercise dominance. This idea ran directly counter to the goal of strengthening the principled, inclusive network, which was built on the notion that all nations, not just China, should have a role in determining the region’s path. For a time, the White House, too, adopted the phrase, after the president met with Xi Jinping in 2013. We had thankfully dropped the phrase by the time I was in the Secretary’s office, but China still speaks in such terms, and during my first meeting with a senior Chinese official as Secretary, tried to convince me to as well.

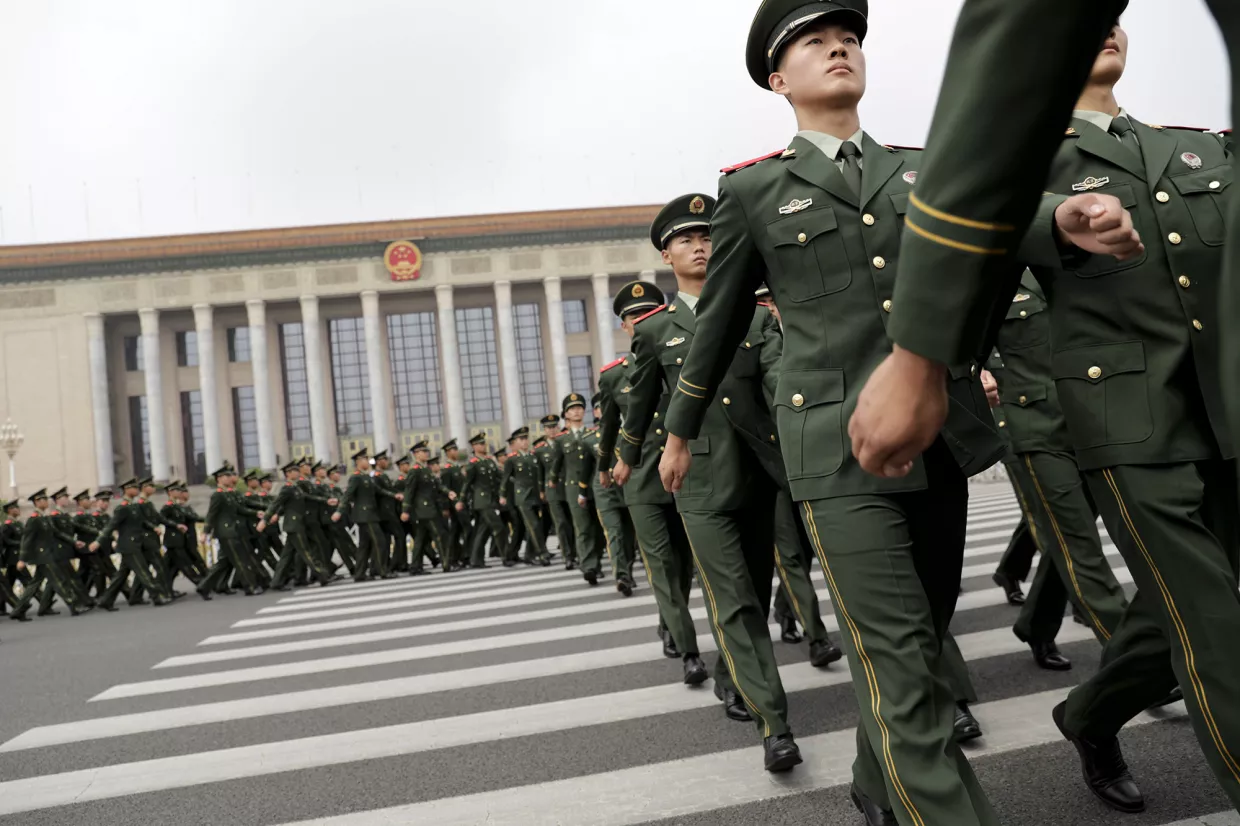

Just four months after I was sworn in as Secretary, Gen. Fan Changlong, vice-chairman of China’s Central Military Commission, entered the Pentagon to the usual pomp and ceremony, greeted by an honor guard and a military band at the River Entrance, where I awaited him.

I had known Fan for some years. Fan surely expected a conversation among old friends. Instead, I confronted him privately but pointedly on a number of issues, and not just China’s unilateral actions in disputed South China Sea island chains. Just a few days before, the OPM hack, and China’s almost-certain responsibility for that theft, had become public. I was furious. I also did not mince words about China’s support for the increasingly provocative regime in North Korea.

Fan was taken aback. It was likely that his direction from his political leaders was to above all else avoid conflict that might disrupt U.S.-China relations—my staff had received such guidance from the State Department and White House, too, but I was not prepared to follow it. As our talk continued, it became increasingly clear that Fan would not be able to report back a “successful meeting”—which to the Chinese meant a meeting free of tension or controversy. During our conversations, Fan sought my agreement to China’s “new model of military-to-military relations.” But I felt it was important to demonstrate that the discussion could not be business-as-usual. I told Fan that I would not agree to a new model of military-to-military relations. I told him our model suited the United States and our friends and others just fine and had been in use around the world for decades. I needed Fan and his military colleagues to understand that China’s actions were destructive to what could and should be a productive U.S.-China relationship. China should not have been provoking Taiwan in 1996, and it should not have been dredging up trouble in the South China Sea 20 years later. Yes, I had long and warm relationships with Chinese officials. But that could not, and did not, affect my responsibility to challenge China’s recalcitrant behavior. Fan went home, doubtless disappointed, but with no ambiguity about the standards we expected the Chinese to uphold.

And that, ultimately, is why I was the only defense Secretary during President Obama’s two terms not to visit China.

Personally, this was deeply disappointing. President Xi even extended an invitation himself: During Xi’s state visit in September 2015, I was among the officials who met with him in the White House residence before the state dinner that evening. Xi sought me out, called President Obama over, and said he would like me to visit China. My boss readily agreed, saying, “Ash, you should do that.”

But professionally, given China’s behavior on a number of fronts, I feared that rewarding China with a visit—which is how the Chinese would see it—would only invite worse actions. Moreover, the Chinese had staged provocations during my predecessors’ visits: In 2011, they tested a new stealth fighter while Bob Gates was visiting in what could only be seen as muscle-flexing and an attempt at embarrassment (one Bob handled with aplomb). During Leon Panetta’s visit in 2014, protestors surrounded U.S. Ambassador Gary Locke’s car and the Chinese defense minister sharply and publicly criticized our Japanese allies while sitting by Leon’s side. Frankly, I also knew that key figures in the Obama administration did not support my stance on China. For all these reasons, there was never a time when I thought visiting China would be productive. I saw little chance for positive accomplishments, and significant risk of additional Chinese one-upmanship.

The Pacific Military Rebalance

While my time as Secretary of Defense did not set the conditions for much improvement in military relations with China, the sum of my efforts as a senior Pentagon official—“weapons czar,” deputy, and Secretary—during the Obama administration did in fact give wide scope for strengthening the military underpinning of the overall Asia-Pacific security network. It was a major preoccupation in configuring our forces, investing in new technology, devising new war plans, and working with old allies and new partners. I sounded this theme at my first major opportunity as Secretary in April 2015 in my speech to the McCain Institute. I noted that the Asia-Pacific would by 2050 contain half the world’s population, and by 2030 would contain the majority of the global economic middle-class. From a security standpoint, the region includes some of the world’s largest militaries, not just China’s massive People’s Liberation Army and Navy, but the powerful militaries of India, Japan, Australia and other nations. With that continued growth in demographic, economic, and military might, I pointed out, “the regional status quo will change. So to secure our enduring interests, and our future that is so closely aligned with the region, we’re changing, too.”5

It is important to put China’s military rise, visible as it is, in proportion. The United States still outspends China on defense every year by a wide margin. Moreover, a nation’s comprehensive military strength is measured by its accumulated spending over many years—the capital stock of its arsenal. By that measure the United States is vastly superior. Next, in comparison to the PLA, the U.S. military is an experienced one, with actual warfighting operations part of almost every U.S. commander’s history. And finally, it is the United States and not China that has the weight of many partners and allies on its side. For all these reasons, it will be a long time before China matches America in comprehensive military power.

The stop in Arizona was a preview of my first major speech on Asia-Pacific policy, at the annual Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore the following month. This conclave was named after the hotel in which it was held. It is the premier annual gathering of defense leaders focused on the Asia-Pacific, much like the Munich Security Conference each winter focuses on Europe and NATO. In my preview in Arizona, I spoke about launching a second phase of the “rebalance” to the Pacific—the Obama administration’s ungainly name for a much-overdue policy of reorienting the nation’s political, diplomatic, economic, and security policy to reflect Asia’s immense impact on the United States and its interests.

The rebalance, first announced in 2011, was born of the realization that, while U.S. national security thinking has disproportionately focused on the Middle East for two decades or more, it is Asia that holds the greatest long-run significance to our country. During my time as Undersecretary and Deputy Secretary, work in the Pentagon, State Department, and National Security Council on the rebalance was intense. Hillary Clinton was a champion of the rebalance as Secretary of State, spurred by the creative and energetic Kurt Campbell, State’s Assistant Secretary of East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

As Deputy Secretary of Defense, and earlier as Undersecretary for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (AT&L) before the rebalance became policy, I was absorbed by the unique military challenges of the vast Asia-Pacific, and I turned the weapons-buying and research arms of the Pentagon in that direction. For a decade, development of new weapons systems and technical innovation had focused on the problems of the wars in the Middle East. We had achieved important successes, such as the rapid development and acquisition of MRAP anti-mine vehicles and of new intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance techniques such as use of drones, aerostats, and multispectral sensors to watch for IED placements. I had worked more than I ever would have wanted to on new approaches to caring for amputees and post-traumatic stress. We had learned important lessons about how to quickly develop and deploy new tools and technologies to defeat emerging threats in Afghanistan and Iraq, and that was vital work.

But while the department was focused on those wars, the Asia-Pacific had been neglected. Threats in the region, including the rise of transnational terror groups, piracy, smuggling, and above all China’s rapidly increasing capabilities, had evolved, but we had not. Admiral Bob Willard, who took over at U.S. Pacific Command in 2009, and Sam Locklear, who succeeded him, were eager for partners in Washington to address those concerns. And so we worked with people like Christine Fox, the director of cost assessment and program evaluation; Policy Undersecretary Michèle Flournoy; Air Force General Mark Welsh; and Navy Admiral Johnathan Greenert to begin refocusing both the footprint of our forces in the Pacific and the systems with which we equipped those forces during the early years of the administration.

So when I came to Shangri-La for the first time as Secretary of Defense, I spoke of initiating a second phase of the rebalance, involving the shift of even more U.S forces to the Asia-Pacific, but above all on investments in high-end capabilities with relevance to the Pacific, with its vast distances and advancing Chinese military capabilities.6

Among the forces I described as shifting were some of our most advanced hardware, such as F-22 and F-35 fighters, the P-8 maritime surveillance plan, the B-2 bomber, the Global Hawk drone, and the V-22 tilt-rotor transport, as well as the Navy’s newest and most advanced surface combatants, such as the new Zumwalt-class stealthy destroyers and Aegis-equipped vessels. Phase two would also involve large investments in new weapons systems in a traditional vein, such as additional Virginia-class submarines with extra numbers of launch tubes for missiles and torpedoes, and development of the brand-new B-21 long-range stealth bomber, the first new bomber in three decades, the design of which I had overseen as Undersecretary of AT&L.

But the new thrust of phase two was new capabilities in high-tech emerging domains such as electronic warfare, cyber, and space. For electronic warfare, the aim was to restore a lead in jamming, counter-jamming, and stealth that had slipped in the years of preoccupation with the Middle East. In cyber, new ideas and funding were for both better defense and new offensive weapons. For space, the key was integrating space capabilities into our conventional war plans; these had too long been viewed as peacetime and intelligence-collection capabilities, not instruments of war. We also found ingeniously innovative new uses for a huge stock of our existing weapons systems, some of which I could announce, such as adapting the Tomahawk land-attack missile for maritime use, but others that could only be hinted at. The Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO), which I started as Deputy Secretary in 2012 and which remained classified until 2016, was established for this purpose—to reimagine existing technologies and apply them to new roles. SCO pursued projects such as the “arsenal plane,” converting existing warplanes into a “flying launch pad” for conventional payloads, linked to other aircraft with fifth-generation sensor and targeting capabilities. I announced that we had adapted the SM-6 surface-to-air missile, built to shoot down airplanes, to attack ships as well. We were exploring electric railgun projectiles for use in missile defense. And all this was just a partial list.

These new investments were the heart of the second phase of the rebalance and they responded to the need to boost our capabilities in a relentlessly demanding Pacific environment. I also pushed for innovation in how we thought about and planned for the Asia-Pacific security environment. A host of smart and thoughtful professionals in the services helped develop new operational and doctrinal concepts that we applied to revised war plans, which were another important part of the rebalance.

China was prone to describe the deployments and investments of our rebalance as Cold War thinking aimed at checking its rise. They were not; the rebalance, like all our Asia policy, was about much more than China, and served many goals. But without doubt these investments were necessary to provide future policy makers with the capability to push back against the second, more bullying and unilateral strain in Chinese foreign policy.

The Rebalance Toward Old Allies and New Partners

(U.S. Navy / Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Cory Asato)

I got the opportunity in June 2015 to do what secretaries of defense are occasionally fortunate enough to do: make history. After my speech at Shangri-La, I traveled to Vietnam. The highlight of my trip, which coincided with the 20-year anniversary of reestablishing diplomatic relations with Vietnam, was a visit to the Vietnamese naval command at Haiphong Harbor—the same harbor whose mining by U.S. forces during the Vietnam War has been the source of Vietnamese anger in the decades since. The Vietnamese arranged for a tour of one of their coast guard vessels—the first time a U.S. Defense Secretary had boarded a Vietnamese warship since the Vietnam War.

The visit wasn’t just symbolic. While there, I was able to announce a small but important agreement for Vietnam to purchase U.S.-made patrol boats, part of a larger trend toward stronger maritime security relationships in the region. I also signed a comprehensive joint vision statement calling for closer defense cooperation between these former enemies across a broad front. This agreement was important because it would greenlight the two militaries to initiate cooperative activities long after I was gone.

My visit was part of a long journey toward closer U.S.-Vietnam ties. Years before, Vietnam veterans such as John Kerry and John McCain had begun working to bridge the emotional gulf between former enemies. In the Pentagon, we worked hard to strengthen defense relationships. My visit in June 2015 helped continue the forward progress leading to President Obama’s own trip to Vietnam in May 2016, in which he announced the lifting of the U.S. arms embargo.

Improving diplomatic and security relationships is essential to bolstering the principled, inclusive network, and it was a critical part of our rebalance—as important as the buildup of U.S. military forces in the Asia-Pacific. Across the region, it enlarged security partnerships with longstanding allies, built on existing non-alliance partnerships, and sought out brand new partners and relationships.

Japan is an example of that first category, a longstanding ally but with a new twist: the sometimes-overlooked fact that China is not the only rising power in Asia. Japan is a rising military power, too, because of legal and constitutional changes of great significance championed by Prime Minister Abe. Japan has long been an economic power, but its impressive military capabilities have been confined since World War II to a strict policy of territorial defense—no projection of Japanese power or the U.S.-Japan alliance to the region as a whole. Abe, recognizing an environment of growing Chinese aggressiveness, violent extremist activity in Asia, and North Korean belligerence, engineered an expansion to enable Japan’s military to operate regionally and even globally. Japan’s willingness to participate in Asian security, including training and exercising with other nations, beyond a purely passive, home-island defense role makes it an increasingly important player in the region.

Another long-standing ally was South Korea. As was traditional for new secretaries of defense, soon after I was sworn in, and in my second overseas trip as Secretary after visiting the Middle East and Afghanistan, I flew in April 2015 to South Korea as well as Japan. The alliance with South Korea is naturally focused on deterring North Korea and defending the South in the event of war. Missile defense was the most visible example of closer cooperation with South Korea. When I was Undersecretary and Bob Gates was Secretary, we began upgrading the capabilities and increasing the numbers of our Ground Based Interceptor missile defenses in Alaska and California. These moves were controversial at the time, with some commentators suggesting they would antagonize Russia and China. Both falsely alleged that these defenses could intercept their missiles and not just North Korea’s. We didn’t want the United States to find itself down the road vulnerable to a North Korean missile and nuclear warhead capable of reaching our homeland. Today, the importance of this controversial decision taken years ago is clear.

Similarly, during my time as Secretary, we sought to continue building our combined capabilities with South Korea. After much discussion, South Korea’s agreement to allow the deployment of our THAAD missile defense system was an important step toward countering North Korean provocations. China’s loud but unjustified criticism of this deployment has not overridden the judgment of successive South Korean presidential administrations that THAAD is a necessary counter to North Korea’s reckless pursuit of a wide range of ballistic missile technologies. In addition to missile defense, we made changes in the U.S.-ROK war plans for defense of the South, in command and control, and in improvements to weapons systems for both our forces.

The North Korean state owes its existence and its survival to China’s economic, political, and military support. Yet time and again, China has chosen to tolerate or even encourage North Korean misbehavior—to choose its own, narrow (and in my mind, misguided) goals over the principled good of the entire region, even in the matter of Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons. My public and private argument to the Chinese has been that actions like this aren’t just a problem for the United States. They’re a problem for the entire region—and especially for China. War on the Korean peninsula would do incalculable harm to China’s rise as an economic and political power. If China has in the past been concerned mostly with preserving North Korea as an irritant to and buffer against the United States, Kim Jong Un is rapidly outliving his usefulness to Beijing. There is no more urgent security challenge in the region than North Korea, and U.S. policy must continue to push the Chinese to do more to prevent crisis from turning into catastrophe. It’s true that China hasn’t been willing or able to do much, but we should continue to try.

Important as the North Korean threat is, South Korea, like Japan, is increasingly thinking in broader regional security terms. The United States needed to encourage this important ally to rise as a regional power. I was able to help foster a cautiously growing trilateral relationship with South Korea, Japan, and the United States, demonstrating the ability of the network to flex and adapt. While I was Secretary, the North Korean threat and China’s rise pushed Japan and South Korea, with substantial U.S. assistance, to strengthen their own security partnership, transforming what was once a pair of bilateral relationships with the United States into an increasingly substantive trilateral partnership. This was not easy for either nation; there is traumatic history between the Japanese and the Koreans, and after many decades, it can still be a fraught relationship. At my first trip to the Shangri-La Dialogue as Secretary in June 2015, I convened a first-of-its kind trilateral meeting between defense ministers of the three nations. So sensitive were both nations that Assistant Secretary Dave Shear had to negotiate the shape of the table. (We decided on an equilateral triangle.) The first conversation was strained, and faces were stony; I felt a little like a party host trying to get strangers to chat. In photos of that first meeting with South Korea’s Han Min Koo and Japan’s Gen Nakatani, I’m the only one smiling.7 But by the time we met again in 2016, the conversation was much lighter; I even almost—almost—got the ministers to smile for the cameras.

Australia, already a close ally, became an increasingly pivotal player in the network. An important plan to shift from a concentrated force presence in a few locations, such as Okinawa, to a more dispersed posture included a rotational force presence in Darwin, Australia. China’s economic influence on Australia is a large and somewhat underestimated factor in Asian affairs; China is a major export market for Australian agriculture. Despite that influence, we were able to reach a cost-sharing agreement with Australia on our troop presence in Darwin, to conduct larger exercises with the Aussies, and to increase cooperation on maritime security issues such as anti-submarine warfare. Together with Australia’s substantial role in the counter-ISIS campaign, these steps demonstrated the value Canberra places on our bilateral relationship and a broader principled Asian security network.

India is another example of how the strategic benefits of the principled, inclusive network can overcome hesitation. Once deeply skeptical of U.S. influence in South Asia, India became a more active participant in regional security during my two years as Secretary of Defense than at any time in its history.

I met with Indian Defense Minister Manohar Parrikar at least half a dozen times, holding as many bilateral conversations with him as any of my other counterparts around the world. I knew the Indians well from past assignments; as Leon Panetta’s deputy, I had led the Defense Technology and Trade Initiative, or DTTI, with India that began breaking down the Cold War barriers between our two militaries. Those barriers resulted from India’s championing of the so-called Non-Aligned Movement of developing nations that refused to take sides in the ideological conflict between Washington and Moscow.

A second barrier was technological: despite non-alignment, India has bought many weapons systems from Russia. These were incompatible with U.S. systems. U.S. technology export controls were still in place from that era, when we had not wanted to comingle our systems with Russian systems for fear of espionage. Finally, our continuing but rocky relationship with Pakistan—a necessity in view of the porous border with Afghanistan, Pakistan’s inadequately secured nuclear weapons, and Pakistan’s historic role as a base for terrorists—was an irritant to India. We needed to break these barriers down.

Importantly, in June 2016, India became a so-called “major defense partner” of the United States, a diplomatic status allowing DoD to institutionalize closer ties including military-to-military relations and defense technical issues, and we concluded an agreement to enable cooperation on logistics.

Many factors led to India’s decision to seek closer ties to us: its growing economic and political confidence, its assessment of the strategic situation on the subcontinent, and the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. Growing nervousness over China’s behavior from the South China Sea to the Himalayan border region played a pivotal role. Under Modi, India was pursuing two major initiatives. One, called “Make in India,” stressed development of indigenous technology and manufacturing. I called the DTTI our “handshake” with Modi’s technology and industrial policy. India was also seeking to grow beyond its historic preoccupation with its neighbor Pakistan and follow a broader “Act East” policy. At the same time, of course, we were looking to extend the Pacific Rebalance to the west. The result was something I referred to as the “second handshake.” The two handshakes together forge a partnership with the potential to be as important to our two nations and to the region’s network as our alliances with Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia also strengthened their commitments to the network. Singapore is an Asian bellwether of attitudes toward China. Its population and political leadership, largely ethnic Chinese, has both a kinship with China and a healthy skepticism of its aims. As a barometer of China’s image and influence in the region, I took the growing Singaporean appetite for closer security ties with us and with other friends and allies in the region as a positive sign for the network. Following a long tradition of Singaporean tutelage of Americans in the ways of Asia, dating in my case to meetings with the legendary founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, I consulted frequently with Defense Minister Ng. He and his wife became good friends of my wife, Stephanie, and me.

So, clearly, the network is growing and strengthening. China, meanwhile, stands virtually alone. As I sometimes ask my students at Harvard Kennedy School, “How many dependable allies does China have in the Asia-Pacific?” Unless you think Kim Jong Un is dependable, the correct answer is “zero.” This is a testament to wise U.S. policy, to Chinese missteps, and more than anything to the powerful idea of a principled network that bestows security and prosperity. But this progress does not mean that the rebalance to the acific was an unbroken chain of successes.

Asia, China, and the Future of the Principled, Inclusive Network

(U.S. Coast Guard photo / Petty Officer 2nd Class David Weydert)

For more than two decades, I worked to strengthen military and diplomatic ties with China, alongside scores of other U.S. and allied officials, all of us sincere in our belief that China could be encouraged to join the principled, inclusive network that has served as the backbone of regional security since the end of World War II. It is easy for me to imagine having used my time as Secretary of Defense to solidify those ties and bring China into closer partnership with the United States and the other participants in the network.

That was not to be. It is difficult to look back over China’s actions in recent decades and continue to argue that China accepts the principled, inclusive network. The domineering, unilateral strain in its policies appears, time after time, to have triumphed over the strain that values partnership and integration. In the Taiwan Strait, on the Korean Peninsula, in cyberspace, in global trade—at nearly every turn, China’s leaders have chosen isolation over integration and confrontation over inclusion. China appears to have concluded that the United States dominated Asia for 70 years, and now it’s China’s turn. This badly misunderstands our role in the postwar Asian security network, and ignores a golden opportunity for China to become a full participant and enjoy the same benefits that we and a growing number of Asian allies, partners, and friends have enjoyed.

What does China’s choice mean for U.S. policy? First, it means the rebalance begun under President Obama should continue, especially the military aspects of the rebalance. We must continue to invest in the innovative systems and ideas required to counter China’s military capabilities. We must have the quality and quantity of forces necessary to prevent Chinese aggression if we can, and counter it if we must. We must also continue to build stronger military partnerships in the region, with established allies such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia as well as newer partners such as Vietnam and India. Partnership is at the heart of the principled, inclusive network, and the stronger the ties among the United States and its partners, the better off we all are.

If China has chosen isolation over partnership, the United States, too, has a choice. The Asian security network has served our interests well, and it can continue—but only if the United States continues to believe in it. I fear our nation has lost confidence in the network approach. Over the last three presidential administrations, including the current one, we have struggled economically, diplomatically, and militarily, to muster coherent support for the principled, inclusive network. Without U.S. leadership and support, the network will be replaced by another, parallel network China is seeking to erect. The China-proposed network would include such initiatives as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (IAAB) and One Belt, One Road (OBOR)—both of which would be detrimental to U.S. interests. The IAAB, a potential rival to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, would not match the high standards of the WB and IMF in relation to governance, environmental, and other safeguards—and OBOR is likely to extent China’s political influence more than it extends actual property.

The parallel network proposed by China would serve China’s interests, replacing principle with brute force and inclusion with dominion.

Notes

- Schmidt, Michael S. “In South China Sea Visit, U.S. Defense Chief Flexes Military Muscle.” The New York Times, April 15, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/16/world/asia/south-china-sea-us-ash-carter.html.

- Schmidt, Michael S. “In South China Sea Visit, U.S. Defense Chief Flexes Military Muscle.” The New York Times, April 15, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/16/world/asia/south-china-sea-us-ash-carter.html.

- United States Department of State. Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs. Limits in the Seas: China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea. No. 143. December 5, 2014. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/234936.pdf.

- For example, see Ku, Julian. “The US Navy’s “Innocent Passage” In the South China Sea May Have Actually Strengthened China’s Sketchy Territorial Claims.” Lawfare, November 4, 2015. https://www.lawfareblog.com/us-navys-innocent-passage-south-china-sea-may-have-actually-strengthened-chinas-sketchy-territorial

- Carter, Ashton B. “Remarks on the Next Phase of the U.S. Rebalance to the Asia-Pacific.” Speech, McCain Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ. April 6, 2015. https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech-View/Article/606660/remarks-on-the-next-phase-of-the-us-rebalance-to-the-asia-pacific-mccain-instit/

- Carter, Ashton B. “A Regional Security Architecture Where Everyone Rises.” Speech, IISS Shangri-La Dialogue, Singapore. May 30, 2015. https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech-View/Article/606676/iiss-shangri-la-dialogue-a-regional-security-architecture-where-everyone-rises/

- See photo at: https://www.defense.gov/Photos/Photo-Gallery/igphoto/2001141711/

Carter, Ash. “Reflections on American Grand Strategy in Asia.” October 2018