Introduction

This paper aims to articulate the absence of Indigenous people in Arctic climate change news coverage and to enumerate approaches for generating resonant, representative, and ethical stories in the white hot center of climate change.

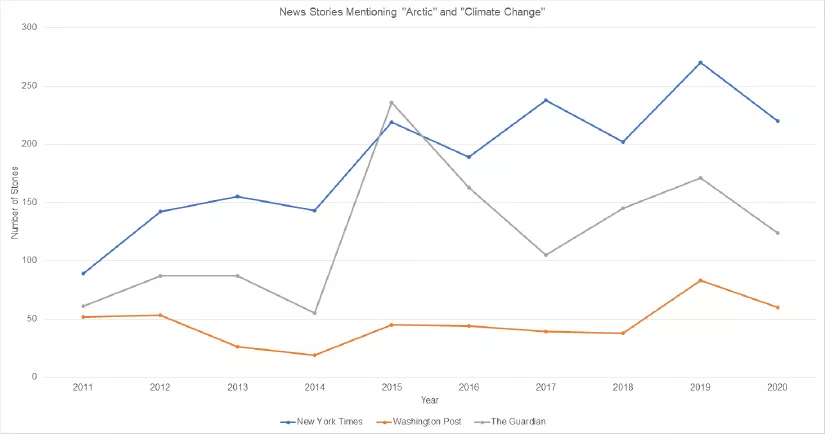

As temperatures have increased in the Arctic, so too has media interest in the region. A keyword analysis conducted using the Factiva database revealed that the number of news stories mentioning “Arctic” and “climate change” doubled in The Guardian in the past decade. During that same period, coverage increased by 2.5 times in the New York Times.

Yet, a population that is severely impacted by thawing permafrost and melting sea ice—the Indigenous people who live in the Arctic—are scarcely represented in the media.1 A separate analysis of news stories broadcast or published in a recent five year period including the keywords “climate change” and “Arctic” demonstrated that coverage focused primarily on science rather than on human subjects.2 When people were included in environmental reporting, they were typically non-resident experts like scientists, policy makers, or activists.

This type of coverage, often brimming with data and favoring outsider expertise, does not necessarily resonate with the public. In a survey of more than 10,000 people inside and outside of the Arctic, low and even decreasing interest in climate change was expressed.3 A range of theories have been posited to explain the global gap in concern and action relative to the severity of the effects of climate change. Behavioral scientists suggest that people freeze in the face of an issue so big that no individual can make a difference.4 And, “doom and gloom” reporting on environmental degradation only reinforces paralysis by presenting problem-oriented narratives without offering solutions.5 Yet, there is a bright spot in climate change communications: human-centered storytelling. This approach, proven to win hearts and minds, has potential to boost the impact of Arctic climate change reporting, and crucially, to increase the representation of Indigenous people in that coverage.6 An emergent framework for conducting community-engaged research in the sciences may prove to be useful for developing expanded journalism practices.

Elevating Indigenous Knowledge

The Arctic is home to a heterogeneous population comprised of more than forty different ethnic groups.7 Ten percent of the region’s four million residents identify as Indigenous.8 Yet, from colonial explorers to modern-day scientists, research in the Arctic has historically been conducted with little acknowledgement of, or regard for, the people living there.9 Only in recent decades have scientists begun to earnestly embrace Indigenous ways of knowing in their research. Indigenous knowledge, as defined by the Inuit Circumpolar Council, is:

A systematic way of thinking applied to phenomena across biological, physical, cultural and spiritual systems. It includes insights based on evidence acquired through direct and long-term experiences and extensive and multigenerational observations, lessons and skills. It has developed over millennia and is still developing in a living process, including knowledge acquired today and in the future, and it is passed on from generation to generation.

By valuing ways of knowing equally, Indigenous knowledge holders and scientists can work together to generate mutually beneficial research. For example, on the semi-arid land of Australia’s Ltyentye Apurte community, co-produced research has led to improved erosion control.10 And in Mazvihwa, Zimbabwe, collaboration between scientists and residents has armed Indigenous people with the information necessary to make land use decisions that balance farming needs and forestry protection.11 Co-produced initiatives in the Arctic have achieved success as well. For example, biologists and Yupik hunters teamed up in Alaska to gather information about the threatened Pacific Walrus population. As a result of this research, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was able to determine that the walrus population was in fact strong. Vera Metcalf, director of the Eskimo Walrus Commission, noted that the collaboration represents an instance in which, “Our Indigenous voice is being heard.”12

Co-production is not, however, a panacea. It is at odds with long-standing colonial methods of knowledge production and complications can be plentiful. Research institutions continue to struggle to create equitable agreements concerning data ownership.13 In spite of increased codification of best practices, Indigenous people often remain minimally involved in projects intended to be collaborative.14 And when engaged as full participants, too often Indigenous people are not fully recognized for their roles, particularly in public presentation and media narratives.15

Narrative Reforms Big and Small

Just as the “the framework, expectations, and design of the research [in the sciences] must itself be decolonized,” so too must media narratives and practices related to the Arctic.16 Journalists have long stated that media affect what people think about, not what they think, but in the last thirty years, data have demonstrated that the media do in fact influence what people think through the very process of telling them what to think about.17 Or, in the case of Indigenous people, what not to think about. News coverage in the United States and elsewhere renders Indigenous people virtually invisible.18 When Indigenous people are occasionally included in reporting, they are often reduced to simple caricatures or negative stereotypes.19 As a result, MEDIA INDIGENA’s founding Editor-in-Chief, Rick Harp, began podcasting. He writes on his organization’s website:

Regrettably, when it comes to mainstream coverage of events and issues involving Indigenous peoples, we all too often experience media at their worst. That’s because, when push comes to shove, Canadian media will always revert to their default perspective: that of the needs, interests and aspirations of the larger non-Indigenous society.

For Indigenous people, the consequences of this mainstream bias vary. Where our stories are overlooked, we remain out of sight, out of mind. Where distortions of who we are and what we want are rendered grounds for incitement, we become threats or targets. In such cases, media plays at ‘objectivity’ swiftly evaporate in favour of sensationalist peddling of fear, anxiety and resentment.

So while I make media out of an admittedly nerdy love for every minute aspect of the craft, I’m also driven by a core belief that stories can be truly life or death. And out of such consequences comes a cause—to share stories which keep Indigenous peoples alive, in every sense of the term.20

Sources like MEDIA INDIGENA, as well as other podcasts, blogs, and alternative news outlets, greatly contribute to the media landscape but they do not correct the omissions in the mainstream media’s coverage. By enacting narrative reform in large and small ways, news organizations have the opportunity to rebuke essentialist depictions of Indigenous people and to create more salient stories about climate change.21

When applied to journalism, the co-production framework developed in the sciences could shift Arctic narratives by availing the resources, reach, and expertise of mainstream newsgathering organizations to Indigenous knowledge holders. In this model, Indigenous participants are recognized and remunerated as co-authors. The act of storytelling is treated respectfully and acknowledged for its power to bind communities, shape the human experience, and convey essential lessons about all aspects of existence, including climate adaptation.22 And, in drawing on this narrative tradition, Indigenous media representation stands to increase as, “Indigenous stories place Indigenous people at the center of our/their research and its consequences.”23

Whereas western journalism practices can be extractive in nature, collaborative storytelling initiatives aim to be additive. Co-production in the news context has the potential not only to improve the vividness and efficacy coverage of the Arctic, but to serve as a capacity building tool for participants and their communities. Working alongside established journalists, Indigenous people can grow their networks and skill sets, opening up job pathways in journalism, where Indigenous writers are grossly underrepresented. (The United States-based Native American Journalists Association, a professional organization that encourages accurate, contextual coverage of Indigenous people, recently found that in 2018 and 2019, only 7% of stories written about Native Americans were authored by Native Americans.24)

Collaborative storytelling projects cannot be realized unless a variety of conditions are met. Journalists must be prepared to grapple with ingrained beliefs regarding expertise, authority, and decision-making, not to mention Western concepts of proof and fact. Co-produced news also requires the participation of Indigenous knowledge holders who may be rightfully skeptical due to generations of abuse and oppression at the hands of colonizers. And finally, daring outlets must possess the resources to fund multi-author projects during an era of epic budget cuts in newsrooms that have made even standard reporting difficult to execute. Funders like the Pulitzer Center and the MacArthur Foundation can offset costs by offering travel grants promoting exchange between Indigenous contributors and journalists as well as money to experiment with a form of storytelling that can only be developed through practice. Partnerships between journalism schools across regions may also be useful in making connections between students separated by geography and in providing access to infrastructure and funding.

While developing co-produced stories stands to be a resource-intensive endeavor, many simple strategies are available for journalists to advance Arctic narrative reform immediately.

Amplify Indigenous voices: Elevate Indigenous creators by sharing and crediting the work of Indigenous storytellers, scholars, and artists on social media channels and elsewhere.

Choose a new story: The Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the world and, as an aside, Indigenous people will be impacted first. Some version of this article has been written countless times.25 To improve reporting on the Arctic, other angles—and other stories altogether—should be explored.26 Cultural vitality, availability of healthcare, and food security in the Arctic are a few amongst many topics that are rarely addressed in mainstream media.27

Include diverse Indigenous perspectives: Hire, train, and elevate Indigenous photographers, writers, and researchers to tell their own stories of living in the changing Arctic.

Do not rely solely on scientists, policy makers, and activists as sources to provide insight on climate change.\

Endeavor to diversify the voices of Arctic residents by including women, youth, and others who are not typically represented in reporting on the region.

Develop dimensional, ethical portrayals: Be wary of exploitive uses of Indigenous suffering that are intended to prompt a response to climate change but that do not benefit the very Indigenous communities that are portrayed.28 Aim for depictions of Indigenous people that transcend reductive tropes.

Read press releases distributed by Indigenous organizations: Journalists, especially those not based in the Arctic, should look to Indigenous groups to learn what stories are most important to them. In lieu of a robust network of Indigenous sources, press releases distributed by Indigenous-led organizations like the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Saami Council can be good places to start.

Review existing guidelines: A number of Canadian organizations have developed comprehensive guides for writing about Indigenous people, including "Reporting in Indigenous Cultures," "Style Guide for Reporting on Indigenous Peoples," and "Interviewing Elders: Guidelines from the National Aboriginal Health Organization."

In addition to physical harm, the lived experience of climate change can cause shock, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress syndrome.29 Journalists should be prepared to consider these factors when speaking with people in affected regions.

Conclusion

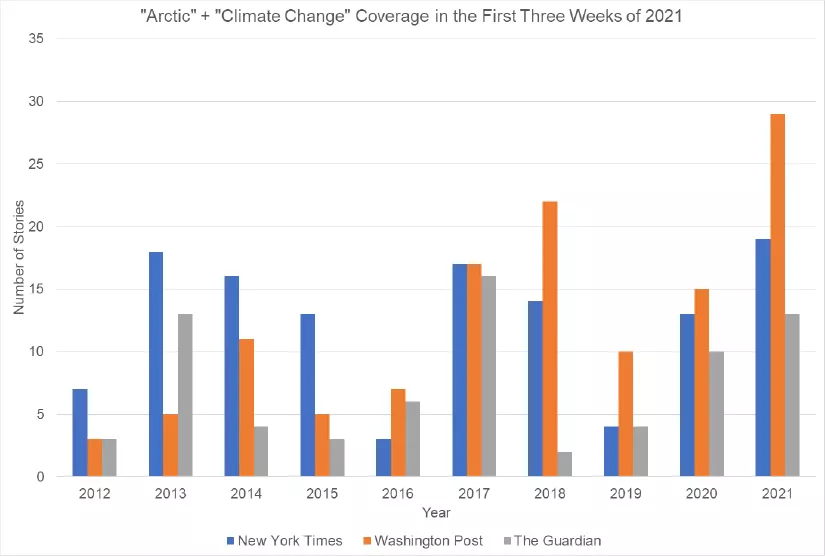

If the first few weeks of 2021 are any indicator, there will be more reporting on Arctic warming this year than ever before. [Appendix 1] To expand the narrative about the region, its people, and climate change, mainstream news reporting must involve Indigenous people in meaningful ways. Through approaches ranging from quick and straightforward to intensive and experimental, there is real potential to tell truer, more resonant stories of the Arctic that involve Indigenous voices and knowledge, starting today.

Agsten, Allison. “Reforming the Arctic Narrative: Indigenous Storytelling, Journalism, and the Potential of Co-Production in the North.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, June 2021

- Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, “Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples,” n.d., 3.

- Elizabeth Arnold, “Doom and Gloom: The Role of the Media in Public Disengagement on Climate Change,” Shorenstein Center (blog), May 29, 2018, https://shorensteincenter.org/media-disengagement-climate-change/.

- Paulina Pakszys et al., “Changing Arctic. Firm Scientific Evidence versus Public Interest in the Issue.: Where Is the Gap?,” Oceanologia 62, no. 4, Part B (October 1, 2020): 593–602, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceano.2020.03.004.

- “Why We Keep Ignoring Even the Most Dire Climate Change Warnings,” Time, accessed November 7, 2020, https://time.com/5418690/why-ignore-climate-change-warnings-un-report/.

- Elizabeth Arnold, “Doom and Gloom.”

- Abel Gustafson et al., “Personal Stories Can Shift Climate Change Beliefs and Risk Perceptions: The Mediating Role of Emotion,” Communication Reports 33, no. 3 (September 1, 2020): 121–35, https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2020.1799049.

- “Arctic Indigenous Peoples - Arctic Centre, University of Lapland,” Uni of Lapland, accessed January 16, 2021, https://www.arcticcentre.org/EN/arcticregion/Arctic-Indigenous-Peoples.

- “Arctic Peoples,” Arctic Council, accessed January 16, 2021, https://arctic-council.org/en/explore/topics/arctic-peoples/.

- “An Inuit Critique of Canadian Arctic Research,” Arctic Focus, accessed January 10, 2021, //www.arcticfocus.org/stories/inuit-critique-canadian-arctic-research/.

- Rosemary Hill et al., “Knowledge Co-Production for Indigenous Adaptation Pathways: Transform Post-Colonial Articulation Complexes to Empower Local Decision-Making,” Global Environmental Change 65 (November 1, 2020): 102161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102161.

- M. V. Eitzel et al., “Indigenous Climate Adaptation Sovereignty in a Zimbabwean Agro-Pastoral System: Exploring Definitions of Sustainability Success Using a Participatory Agent-Based Model,” Ecology and Society 25, no. 4 (2020): art13, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11946-250413.

- Richard Stone Sep. 9, 2020, and 11:55 Am, “As the Arctic Thaws, Indigenous Alaskans Demand a Voice in Climate Change Research,” Science | AAAS, September 9, 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/09/arctic-thaws-indigenous-alaskan….

- Laura Zanotti et al., “Political Ecology and Decolonial Research: Co-Production with the Iñupiat in Utqiaġvik,” Journal of Political Ecology 27, no. 1 (January 28, 2020): 43–66, https://doi.org/10.2458/v27i1.23335.

- “Principles for Successful Knowledge Co-Production for Sustainability Research | Future Earth,” accessed January 17, 2021, https://futureearth.org/2020/01/21/principles-for-successful-knowledge-….

- Cassandra Willyard, Megan Scudellari, and Linda Nordling, “How Three Research Groups Are Tearing down the Ivory Tower,” Nature 562, no. 7725 (October 3, 2018): 24–28, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06858-4.

- Ulunnguaq Markussen, “Towards an Arctic Awakening: Neocolonalism, Sustainable Development, Emancipatory Research, Collective Action, and Arctic Regional Policymaking,” in The Interconnected Arctic — UArctic Congress 2016, ed. Kirsi Latola and Hannele Savela, Springer Polar Sciences (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017), 305–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57532-2_31.

- Robert M. Entman, “How the Media Affect What People Think: An Information Processing Approach,” The Journal of Politics 51, no. 2 (1989): 347–70, https://doi.org/10.2307/2131346.

- July 18, 2018 | Rebecca Nagle | Media, and Race/Ethnicity, “Research Reveals Media Role in Stereotypes about Native Americans - Women’s Media Center,” accessed January 18, 2021, https://womensmediacenter.com/news-features/research-reveals-media-role….

- Raymond Nairn, Tim Mccreanor, and Angela Barnes, Mass Media Representations of Indigenous Peoples MURF Report, 2017.

- “What We’re About – MediaINDIGENA,” accessed March 31, 2021, https://mediaindigena.com/what-we-are-about/.

- The phrase “narrative reform” has been used in another context by the scholar Mariela Olivares to describe “societal perception and concomitant legislative processes.”

- Gregory A Cajete, “Children, Myth and Storytelling: An Indigenous Perspective,” Global Studies of Childhood 7, no. 2 (June 1, 2017): 113–30, https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610617703832.

- Aman Sium and Eric Ritskes, “Speaking Truth to Power: Indigenous Storytelling as an Act of Living Resistance,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2, no. 1 (May 9, 2013), https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/19626.

- “2020 NAJA Media Spotlight Report,” Native American Journalists Association, February 5, 2020, https://najanewsroom.com/2020-naja-media-spotlight-report/.

- Heather Exner-Pirot, “How to Write an Arctic Story in 5 Easy Steps,” ArcticToday (blog), December 4, 2018, https://www.arctictoday.com/write-arctic-story-5-easy-steps/.

- Elizabeth Arnold, “Doom and Gloom.”

- Henry P. Huntington et al., “Climate Change in Context: Putting People First in the Arctic,” Regional Environmental Change 19, no. 4 (April 1, 2019): 1217–23, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01478-8.

- Ella Belfer, James D. Ford, and Michelle Maillet, “Representation of Indigenous Peoples in Climate Change Reporting,” Climatic Change 145, no. 1 (November 1, 2017): 57–70, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2076-z.

- “EA_Beyond_Storms_and_Droughts_Psych_Impacts_of_Climate_Change.Pdf,” accessed January 19, 2021, https://ecoamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/eA_Beyond_Storms_and_….