In a spectacular technological failure, Kenyan officials recently abandoned the electronic transfer of election results and switched to manual tallying. This was not expected in a country that developed the now world-famous mobile money transfer system, M-Pesa.

The collapse of the system delayed the announcement of the winner, causing anxiety in a country that witnessed serious post-election violence in 2007 that left more than 1,500 people dead and 250,000 displaced from their homes.

Rumors swirled on social media that the system had been hacked and as result the elections had been fatally compromised. A local civil society organization filed a law suit seeking to have the manual tallying halted. It claimed that the process lacked integrity. The suit was dismissed by the Kenya high court.

The failure was attributed to a variety of technical factors, but the sources of the problem have deeper roots.

It is widely held that technology tends to advance faster than the social institutions needed to govern it. This is a case where institutional innovation in governance outstripped the capacity of the country to provide the technical and managerial infrastructure needed to efficiently manage complex elections in a timely, transparent, and credible manner.

Kenya spent nearly 20 years negotiating a new constitution that was finally adopted in 2010. It provides for six categories of elections including votes for a president, national assembly members, female representatives to new counties, senators of a new chamber, governors, and civil leaders.

On the first polling day (March 4) the biometric voter identification kits failed. About 36 hours into the process the electronic transmission system relaying data from 33,400 polling stations supported by 240,000 clerks to a central tallying center ground to a halt.

Various explanations such as data overload and a bug in the system were offered but could not stand the test of logic. For example, officials asserted that a bug in the system was multiplying "reject" votes by eight. But the numbers of rejected votes were not always even, so this explanation could not hold. The process had in effect failed the credibility test.

In February the press had reported major flaws in the system but the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) denied there was a problem. Similarly, the head of Kenya's main mobile phone firm, Safaricom, wrote to the electoral commission warning of the limitations of the system.

Safaricom, which is partly owned by Vodafone, provided the virtual private network (VPN) for the electronic transmission system. It later said in a statement it was not responsible for the system's breakdown. The polling stations used Safaricom SIM cards and an app with proprietary software provided by the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) installed in the phone. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) funded technical assistance to the process.

Kenya's demand for greater transparency, accountability, and credibility in elections was compromised by the country's poor infrastructure. The high-tech biometric kits failed because of lack of power at polling stations. Officials of the Kenya IEBC were forced to revert to paper registers as laptops ran out of power, which accounted for some of the delays in voting.

There are many unanswered questions relating to technical specifications, procurement arrangements, support services, and training of polling officials that remain answered. These are essentially issues related to the proper approaches needed to deploy complex engineering systems.

Technical challenges quickly overwhelmed the system, as reported by the BBC: "One of the main flaws was that people out in the field had trouble synching the data," according to Erik Hersman, a Nairobi-based co-founder of Ushahidi, an open-source web service created to map the 2007 post-election violence in Kenya.

The co-evolution of basic infrastructure and democracy is now widely appreciated. It is not uncommon to hear arguments that good governance is a prerequisite for effective implementation of infrastructure projects. To a large extent this is true because big infrastructure projects tend to be associated with corrupt dealings.

But the absence of basic rural transportation may reduce voter participation. Alternatively, more polling stations may be needed for isolated communities. This in itself may reduce transparency in the electoral process.

Infrastructure failure is the norm in poor countries but it is taken for granted. In many cases it is passed off as market failure. It affects every aspect of social and economic life from access to medical services to school attendance to delivery of agricultural produce to markets. Where basic infrastructure is built, it is often left to decay because of lack of long-term investment in maintenance and services.

Even advanced countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom have to struggle to raise awareness on the importance of infrastructure for economic renewal. The importance of engineering in economic growth and human wellbeing will be underscored on March 18 by the announcement of the winner of the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering. The aim of the £1million global prize is to recognize and celebrate outstanding engineering advances that have changed the world.

As developing countries continue to aspire to higher governance and development standards, they will also need to ensure that they improve their engineering capabilities and the associated management practices. Failure to do so can lead to humbling reversals to analog days for countries that are aspiring to become important players in the digital age.

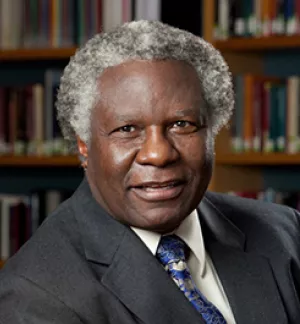

Calestous Juma (@calestous) is Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard Kennedy School and author of The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa (Oxford University Press, 2011). He co-chairs the African Union’s High Level Panel on Science, Technology and Innovation and serves on the judging panel of the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering.

Juma, Calestous. “Technology Trips Over Democracy in Kenya.” Technology+Policy | Innovation@Work, March 8, 2013