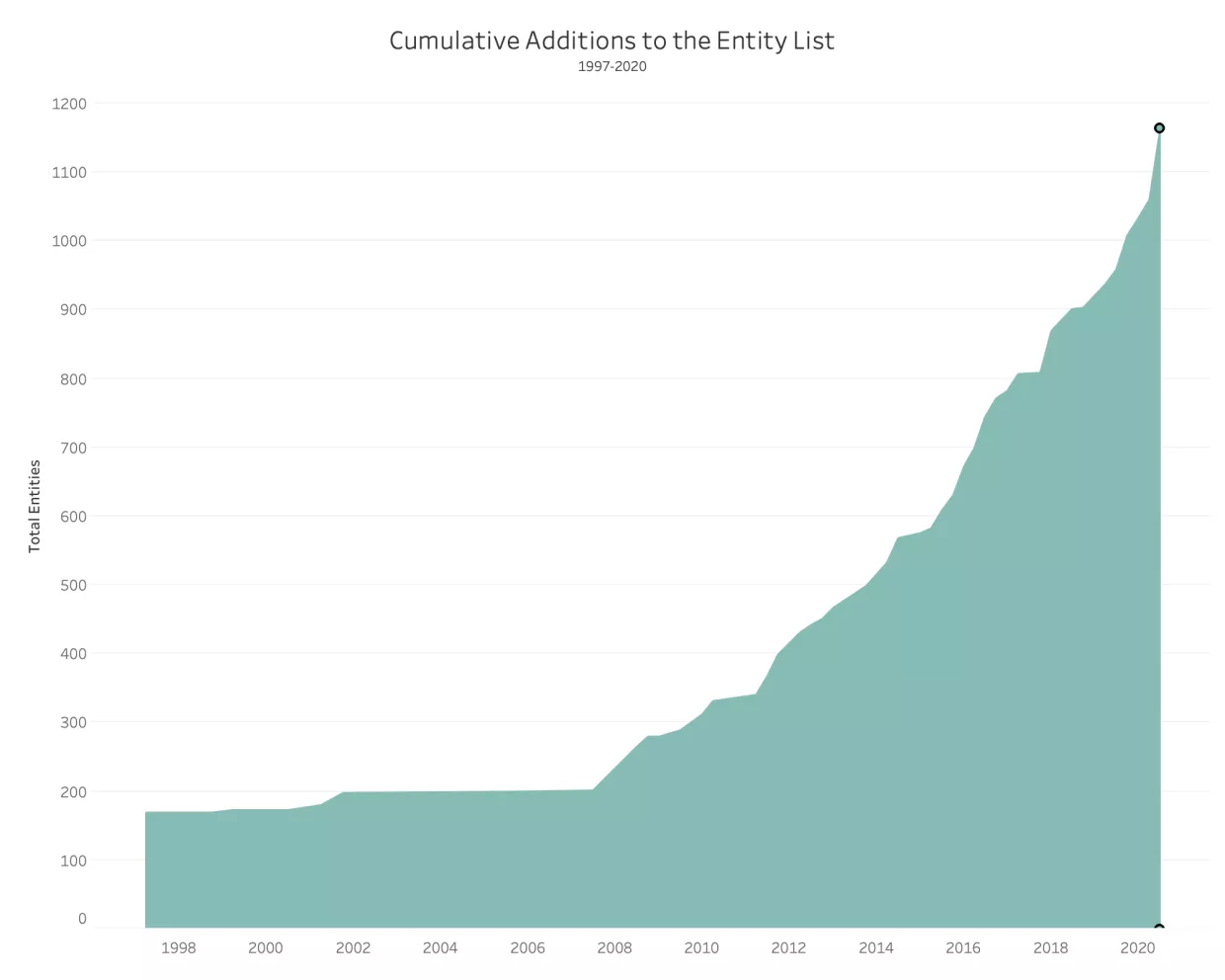

The US government is increasingly relying on export controls to restrict foreign companies from accessing critical made-in-America components. Within the US Commerce Department, the Bureau of Industry Security (BIS) maintains the “Entity List” of blacklisted firms under export control restrictions. This list has traditionally not received much attention, as policymakers tend to focus on more widely publicized Treasury Department and State Department sanctions. However, in the last 10 years the Entity List has increased nine-fold to nearly 1,200 entities, as hundreds of companies from China’s Huawei to Russia’s Gazprom join the ranks of foreign firms prohibited from receiving U.S. exports.

The Economic Diplomacy Initiative (EDI) at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is presenting a first-of-its-kind analysis of the makeup of the Commerce Department’s Entity List, by country, by sector, and by year of addition. Starting with raw data made available by the Commerce Department, we manually grouped blacklisted sub-entities at the parent level to give a clearer view of the companies targeted by export controls. While the Entity List does not include industry tags, we used Federal Register announcements and secondary research to manually assign industry sectors to each entity. The analysis provides a quantitative review of the evolving use of the entity list to shed light on shifting aims of US economic and national security policy.

Overview

While sanctions primarily focus on limiting the movement of money, people, and weapons, export controls focus on limiting the movement of physical goods. The Entity List “is a list of parties for which the United States Government maintains restrictions on certain exports, reexports, or transfers of items.” If a foreign party is on the Entity List, US companies are banned from exporting, reexporting, or transferring items to that party, unless that US company gets a special license requirement that allows them to bypass Export Administration Regulations (EAR 15 CFR Parts 730-774).

Executive orders are the main mechanism for adding companies to the Entity List. For example, EO 13783 added Huawei and 68 Huawei affiliates across 26 destinations to the Entity List in May 2019. Nearly all of the executive orders in the last decade have drawn their powers from the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) and the National Emergencies Act, which give the president power “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat... to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.”

The export controls of the Entity List are different from traditional sanctions. Commerce enforces controls on exports, reexports, or transfers to nearly 1,200 foreign companies. Treasury enforces 8,800 sanctions against financial institutions, governments, and individuals to block the flow of money that would otherwise fund activities dangerous to national security. Lastly, State enforces 900 sanctions primarily relating to stopping the spread of weapons, arms, and nuclear materials and also enforces travel bans.

BIS adds companies to the Entity List often without much fanfare. The Bureau has launched 82 press releases in the last 3 years, but over 400 entities have been added to the list at the time. Some announcements include multiple entities, like the October 19, 2020 addition of 28 Chinese companies for “engaging in or enabling activities contrary to the foreign policy interests of the United States” primarily focused on “human rights violations and abuses in China’s campaign targeting Uighurs”. However, the BIS has simply not made any public announcements on its website for hundreds of blacklisted entities, instead relying on Federal Register notices that may make it difficult to track key updates and changes, a particular challenge for US companies aiming to maintain compliance. The Commerce Department does allow US businesses to provide feedback on blacklisted entities. In March 2020, BIS announced that it would extend its public comment period on Huawei controls, stating, “The Department has received requests from industry to allow for additional comments.”

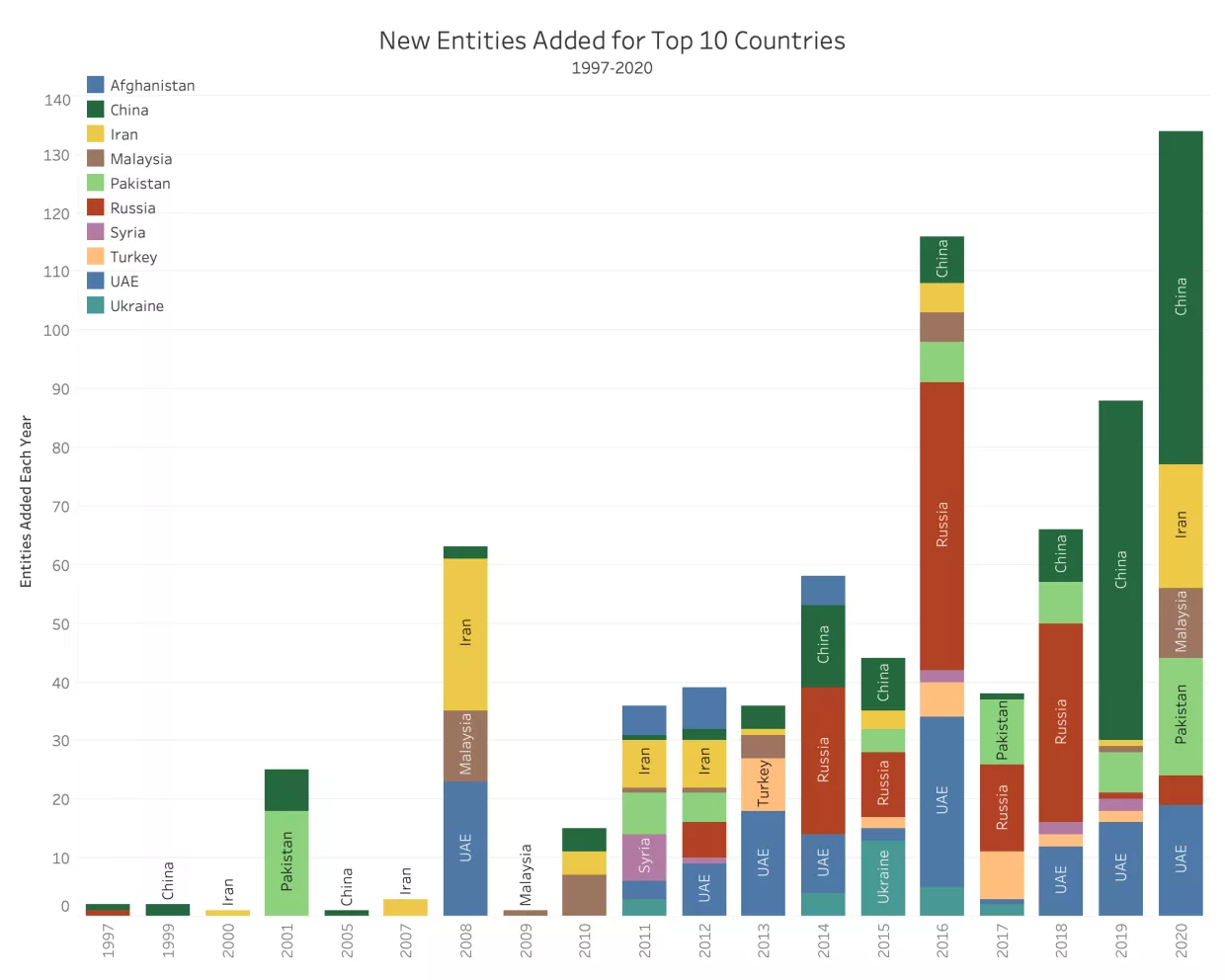

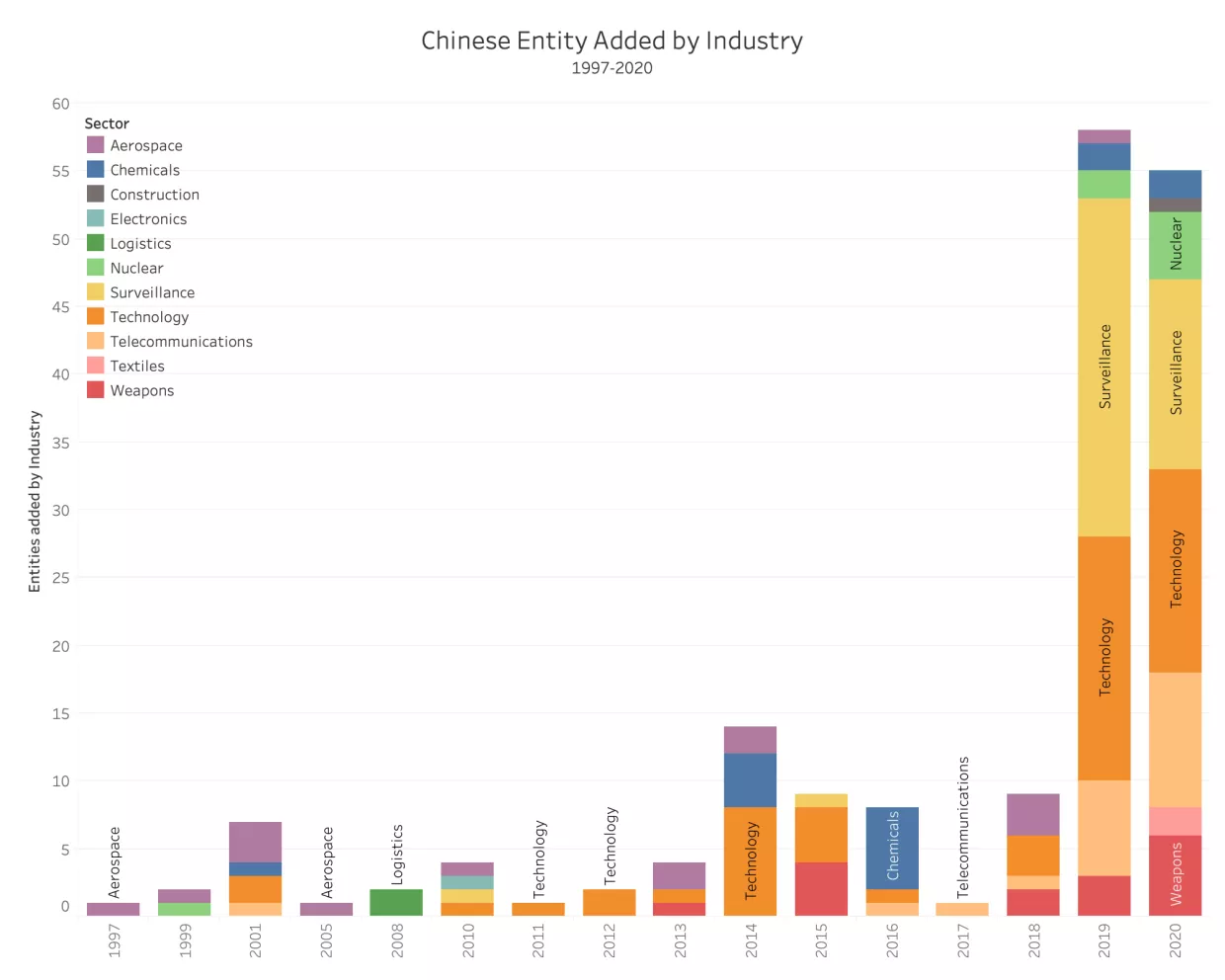

Time-series analysis of the Entity List reveals its rising prominence as a tool of US foreign policy, starting in the Obama years and continuing under the Trump Administration. In the last 10 years (2010-2020), BIS added 832 companies and individuals to the entity list, a 420% increase from the prior 10-year period (2000-2010). Regional focus has shifted from the Middle East to Russia to China over the prior two decades, and the sectoral focus from aerospace and missiles to companies building surveillance equipment and integrated circuits, reflecting the evolving aims and priorities of US foreign policy.

Regional focus

The Obama administration wielded export controls against entities in a number of regions, including in Russia, Iran, and the UAE. This strategy reflected the Administration’s foreign policy objectives, such as: rebuking Russian aggression in Ukraine; increasing pressure on Iran leading up to nuclear negotiations; and halting the UAE’s role as middleman to supply products to banned companies in Syria, Turkey, and Afghanistan.

Beginning in 2014, Chinese entities feature more prominently on the entities list, commensurate with the growing China challenge. As US policymakers navigate trade imbalances, economic competition, and the control of information and data, export controls, which are suited to addressing the economic challenge, have taken on a more prominent role. Accordingly, the US added 58 Chinese parent-companies to the Entity List in one year alone (2019). The Commerce Department has been central, for example, to US strategy to curb the proliferation of Huawei’s 5G telecommunications equipment due to concerns about espionage or sabotage of critical networks.

Sectoral focus

The vast majority of the 180 Chinese companies that have been added in 2020 were in the technology and surveillance space, primarily companies that specialize in artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and integrated circuits. Notable Chinese additions to the entity list include Huawei; SenseTime, the most valuable AI startup in the world; and Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co. and Zhejiang Dahua Technology Co., which are two of the largest video surveillance firms in the world.

Huawei has become the poster child for the Entity List. In 2012, Mike Rogers (R-Mich) gave a speech to the Congressional Intelligence Committee marking the beginning of America’s campaign against Huawei. Representative Rogers argued that Huawei would be added to the Entity List because of its “prolific threats of cyber espionage for the Chinese government.” US officials have maintained that Huawei tech must be kept out of phones, 5G towers, and telco services because of the “backdoors” the company has created to transfer information back to certain agencies. While only a few Huawei sub-entities were added in 2012 during the Obama administration, the Trump administration has added 152 Huawei sub-entities since May 2019. President Biden’s pick for the Commerce Department, Gina Raimondo, has not committed to keeping Huawei on the Entity List, despite growing pressure from the GOP.

Despite the Trump administration’s pleas, the UK still uses Huawei technology in non-core components of its 5G infrastructure.

Longer-term implications

When BIS adds companies to the Entity List, the ripple effects are felt throughout the global economy and political environment.

On the political side, other countries have created corresponding lists of banned US companies to restrict global trade.

China in particular has responded to the US Entity List with one of its own. In September 2020, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) released the “Unreliable Entity List” (UEL) which contains 14 articles outlining the circumstances that will land a company on China’s UEL. For instance, MOFCOM can add entities to the UEL for:

- “Endangering China’s national sovereignty, security, or development interests;

- Or suspending normal transactions with, or applying discriminatory measures against, an enterprise, other organization, or individual of China, which violates normal market transaction principles and causes serious damage to the legitimate rights and interests of the Chinese party.”

When China adds a company to the UEL, the government can then restrict imports/exports, investments in China, entry of any personnel, or cancel any work permits. While MOFCOM has not yet added any companies to the UEL, The Global times which is owned and published by the Chinese government’s official newspaper, has said that China is readying countermeasures against Qualcomm, Cisco, Apple, and suspending the purchase of Boeing airplanes.

The Chinese government created protocols for Chinese companies to follow if they believe they have been unjustifiably penalized by US controls. The rules, published in January 2021, help companies submit grievances to the government which can then enact “necessary counter-measures” in response.

On the economic side, export controls clearly present a trade-off between furthering national security objectives and creating costs for American companies in the form of lost trade opportunities and compliance fees. While the Entity List is essential for upholding US national security, policymakers must also understand the economic consequences.

In addition, experts argue that export controls could harm the competitiveness of US companies in the long term. In the case of semiconductors, for example, China is driving investment into supporting companies and investing in talent to further develop its local capabilities. If US policy succeeds in driving nations to reduce their reliance on American firms, it could lead to longer-term declines in revenue, research and development, and market competitiveness.

President-elect Biden has signaled that he will maintain a hardline stance against Chinese tech exports. However, his administration has noted that America cannot rely solely on its own policy tools to promote global security, but instead wants to create a broad coalition of countries to enforce actions. While the Biden administration will continue to use the Entity List as a tool of economic statecraft, the new coalition-approach may change which countries and companies come into the spotlight.

Special thanks to Castellum.ai for their insights, to Aditi Kumar for her expertise, and to Julia Friedlander and the Atlantic Council for their guidance.

Ney, Jeremy. “United States Entity List: Limits on American Exports.” February 2021