Featured in the Belfer Center Spring 2021 Newsletter »

Introduction

Venture Capital (VC) is in the business of making educated guesses for financial returns. It requires an understanding of the requisites that make a startup succeed and a creative vision of the unknown. Most startups involve some combination of developing technology, undeveloped markets, scarce resources, new teams, unknown product-market fit, and new business models. Given the uncertainty generated from these circumstances, VCs rely on pattern recognition, diligence, and scenario-building to make informed decisions in the interest of their LPs.

Yet, the decisions VCs are making do not just impact LPs, founders, or customers. Instead, the decisions to fund and support various types of technology or innovation impact everyone in society. Indeed, venture-backed startups affect not only how we work, live, and move, but also jobs, the environment, the economy, democracy, human rights, privacy, and safety. Investors in these companies have massive responsibility in how our society is shaped, though they are rarely held accountable for the negative aspects of those outcomes.

That said, a growing number of investors and startups have started to consider not just the financial returns, but also the impact and ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) risks of their decisions, like other asset classes and publicly traded companies have before them. According to estimates, over $30 trillion in assets under management are invested using sustainable strategies such as ESG.1 There are rating agencies, methodologies, and frameworks to assist investors in analyzing returns, in addition to intended and immediate impact, and to evaluate, measure, and report risks. This results in an abundance of data, frameworks, tools, and a long list of impact considerations for companies to measure.

Despite the abundance of tools, there are gaps in these analyses. ESG and impact approaches, as they now stand, do not typically work for VC-backed early-stage technology companies primarily because of their evolving business models and products. In addition, there are limited methodologies to help startups or VCs plan for the possible negative consequences or anticipation of harms as a result of their respective technologies. We believe it is not only the responsibility of the founders or regulators to assess what the negative effects will be on society, but also the responsibility of investors who take credit for innovation, but not the risks. For this reason, we created a software tool, the Venture Capital Public Purpose Indicator (VCPPI) to help VCs and startups anticipate harms and reduce business risks.

The Venture Capital Public Purpose Indicator and this accompanying playbook provide guidance to VCs and startups that are interested in preventing negative consequences and in laying a public purpose foundation. They can be used alongside other existing diligence or planning processes. All of the resources used to create the VCPPI are cited in this playbook.

What is Public Purpose?

...and how is it different from ESG or impact?

ESG is a term used to consider environmental, social and governance risks and internal decision-making factors at a company. There are several different ESG factors and metrics, including industry-specific key issues such as climate change, human capital, labor management, corporate governance, gender diversity, privacy, and data security.2 ESG investing grew exponentially starting in 2004-2005, when 50 CEOs of major financial institutions and corporations came together with the United Nations (UN) to embed environmental, social and governance risk reduction factors in capital markets for better businesses, more sustainable markets and better outcomes for society.3 Historically, ESG—sometimes referred to as triple bottom line (people, planet, profits) investing—has been used for publicly traded assets, with private funds recently embracing ESG metrics. ESG was not directly developed for early-stage technology-first companies.

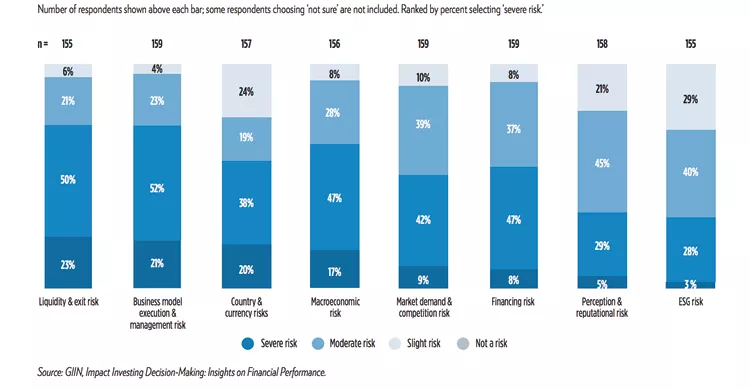

Impact Investing Portfolio Risk

Impact investing refers to capital that supports a company or product that intends to have a positive impact on society.4 Impact investing is often used in early-stage companies to illustrate that a company can make financial returns, as well as generate a positive impact on society. Impact investing does not always consider downside risks or negative impacts on society.

VC + Public Purpose looks at social, technological, and economic challenges in the long-term utilizing 6 themes: the environment, labor and inequality, privacy and security, diversity and inclusion, governance and anti-corruption, and long-term value creation. It combines aspects of ESG and impact investing, considering both internal decisions of technology companies and the external outcomes of these companies, while anticipating any possible negative consequences on society. VC + Public Purpose research is specifically built for venture-backed, early-stage technology-based startups. The evaluation process should lead to structured conversations between impact or generalists investors and startups during diligence, a pivot, or rapid growth. It, therefore, emphasizes the foundation that a startup is building and on the plans they will have for public purpose in the future. Our approach takes into consideration the uncertain and evolving nature of early-stage technology-first companies and aims to contribute to performance, for public purpose can be an economic driver as it relates to growth, profitability, competitive advantage, and liquidity.

Why Should VCs Care About Public Purpose?

“I don’t know how to explain to you that you should care about other people.”

—Lauren Morril

Rising economic instability, inequality, increasing climate crises, public health crises, national security issues, disinformation, online and offline hate crimes, lack of privacy and security of personal identifiable data, mass surveillance, racial injustice and an overwhelming lack of diversity and inclusion in STEM. These are just some areas of society that are almost always objectively considered harmful—for the economy, individuals, and the future. Politicians and regulators attempt to create solutions and, often, point the finger at the next person to blame. Major social media CEOs5 have been questioned by Congress and by journalists on their products and business strategies6; economists have analyzed monopoly power and rent-seeking7; and social scientists have written books exposing the harmful or predatory behavior of technology.8 Rarely, however, do we talk about the responsibility of investors when it comes to their involvement with life-altering technology, influential companies, and the knowledge that they need to be better investors—for the sake of everyone, not just their LPs.

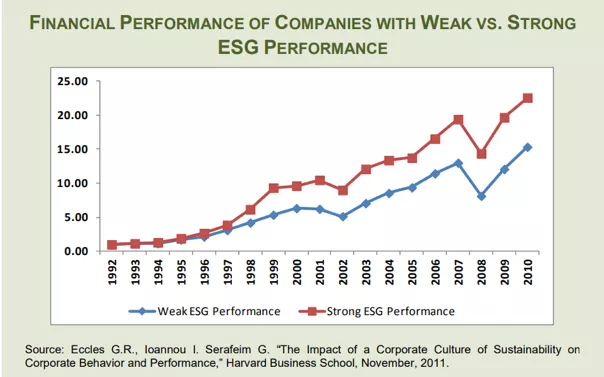

The existence of responsible investing and ESG is due, in part, to investors asking, “How can I do good and do well?”9 The business cases have been made. Companies perform better financially when they have strong ESG performance and diverse employees. Considering public purpose, ESG, or impact is time- and capacity-intensive, but can result in a reduction of legal costs, better public relations, foresight around regulation, improved talent recruitment and retention, potential moats against competitors, lower loan and credit default swap spreads and higher credit ratings.10

Beyond just doing the “right thing,” or doing so for possible compliance or regulations, VCs should be interested in public purpose because their investors are expecting it. According to a Morgan Stanley survey of 110 global institutional asset owners, 95 percent are integrating or considering integrating sustainable investing in all or part of their portfolios—signaling a demand from Limited Partners (LPs).11 On the other side of the equation, in oversubscribed rounds for startups, founders and CEOs are picking investors who align the most on values and mission, often demonstrated by their fund’s public purpose, ESG, or impact thesis.

An innovation ecosystem is beneficial for the general public and capitalism only when everyone has access to it and the technology that derives from it does more good than harm. The efforts that brought us to the moon, as well as gave us computers, the internet, cell phones, and vaccines, all occurred first due to an understanding of public purpose and value, which only then were followed by science and innovation. The “move fast and break things’’ era from Silicon Valley has departed from these values, thereby creating a lot of harm. Innovation can be slower, more thoughtful and tested for the effects—both positive and negative—on multiple stakeholders. As innovators, we should create plans against harm and not just rely on regulators to protect us. We should be creating systemic and innovative solutions to hard problems, in addition to creating wealth and returns.

“Make capitalism inclusive, sustainable, and driven by innovation that tackles concrete problems. That means changing government tools and culture, creating new markers of corporate governance, and ensuring that corporations, society and the government coalesce to share a common goal. We did it to go to the moon. We can do it again to fix our problems and improve the lives of every one of us. We simply can no longer afford not to.”

—Mariana Mazzucato12

The VC Perspective: Business Case Studies

Over 6 months, we spoke to approximately 40 startup investors across geographies in North America, the European Union (EU), Asia and Israel, with fund sizes ranging from $20M to $10B+ AUM and focus areas across Artificial Intelligence (AI), climate, fintech, deep tech, impact, marketplaces, SaaS and consumer tech. Some of the investors we spoke with are generalists, invest through an accelerator, or are from corporate VC; others are public sector investors, investing only in diverse founders, and fewer than 10% invest under an explicit impact thesis as a directive from their LPs. In our conversations, we discussed how these individuals and firms:

- Consider ESG, impact, or public purpose beyond or in parallel to their financial returns, if at all; and

- Assess negative impact, if at all, regardless of their status as an impact investor or not.

We also asked:

- What they need in a diligence tool or system to better measure public purpose in areas such as environment, labor, inequality, human rights, democracy, diversity, privacy, safety, security, anti-corruption and governance in their investments; and

- What their vision of the future is, as it relates to venture capital and public purpose.

From these conversations, a few themes and observations have shown up consistently and informed how we mapped our VCPPI tool.

- ESG vs. Impact vs. Mission Aligned. Frequently, generalist VC funds use the terms “impact” and “ESG” interchangeably. Typically, impact investors make a distinction between ESG and impact. Some investors consider impact in diligence as it relates to the race and gender of the startup’s founders; a company could have a female lead or a BIPOC founder and be considered impact, despite the business model itself not being impactful. Some funds seek to “change the world” or have a strong futures-oriented mission, but explicitly state that they are not impact investors and do not use any widely used frameworks to assess for ESG or impact. Instead, they rely on gut instincts or values set out by the GPs.

- Frameworks & Methodologies. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) are frequently, but loosely, used as a reference point or moral compass when impact investors define their criteria or investment thesis. Despite the abundance of ESG frameworks and methodologies available, impact investors are relying on an amalgamation of organizations such as the MSCI, Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) to create a customized framework that works for their respective firm. Therefore, the analysis often remains siloed and separate from financial reporting and only covers the most obvious possible negative consequences around race, gender, and data security. Some investors look at financial and growth metrics and then assess impact, while others look at these areas in parallel with equal weight or view them as entirely interconnected.

- Long-term value for the public. Regardless of whether they use or invest under “impact” or “ESG,” nearly all investors care about the ultimate influence that the technologies they invest in have on stakeholders beyond customers and investors. Impact or not, most investors seem to agree that a deeper level of scrutiny or diligence could be beneficial to both the company and society in the assessment of negative consequences. That said, at some larger funds, there remain some GPs who believe that these considerations are less intrinsically valuable, but instead more relevant for marketing strategies. Particularly in the early stage, some investors believe that standards, tools or disclosures detract from the “special sauce” of investing.

- Capacity. Time is a huge variable when it comes to how much investors pay attention to impact, if it is not a mandate from their LPs. For understanding the complex layers of impact—the negative consequences and adverse effects on vulnerable communities or economies—requires expertise and time. Sometimes, funds partner with nonprofits or academia to create mission statements or selection criteria. Some larger funds also hire experts in ESG to help with measuring and reporting. Investors also often worry that, if too much time is spent reporting and tracking on impact, then their founders will be distracted from building.

-

Futures-Thinking. Applying a purpose lens to investing at the early stage is hard because often the startup is too early to report on metrics or to answer long-term questions about their business model and supply chain. To make up for these unknowns, investors apply a level of rigor in their diligence for scenario-building, asking future-thinking strategic questions because so much of early-stage investing is about selling a vision and a strategy, as well as about asking founders to answer tough questions about how they plan to act and build. Often, in addition to questions of diligence, investors rely on pattern-matching to make decisions.

“Uncertainty, generally, is something to be avoided. If you can’t predict the outcomes of your actions, you will have a hard time planning and managing. And if others see that your business proposition is uncertain, they will shy away from including your product in their plans. But uncertainty can also shield against competition, allowing you to create excess value. If it does, it is productive uncertainty. Innovations, because they are new, usually come with uncertainties of one sort or another. Founders have to choose the subset of innovations where the uncertainty is productive to have the best chance of succeeding.”

—Jerry Neumann13 - Decision-Making. Many investors have said they would use a tool that helps them analyze public purpose in pre-investment diligence or for follow-on consideration. Some said they would use a tool to flag areas that they would want to monitor with the startup, particularly if they were to take a board seat or board observer role. Some said they would not abandon investments if the company pivoted away from their original intended impact, while others would not double down in further rounds if the company’s choices were considered harmful to the public. A few investors have gone so far as to add language in their term sheets or soft commitment clauses to hold the founders accountable to the impact that they promise to deliver. Investors recognize that there are inherent biases when it comes to making choices for new investments (faster to say no) versus the choices to follow-on existing investments (want to say yes).

- Theory of Change. Many investors interested in public purpose agree that the government, regulation or policy play a role in sustainable solutions. What varies is which key challenges are addressable through the private sector: business models acting as Band-Aid solutions as opposed to systemic change. Some investors recognize that there can be an opportunity with policy (e.g., climate tech). Some have heightened sensitivity to areas that are highly regulated or dominated by policy or government. Some investors believe society’s issues can be solved by markets or technology and agree that regulation limits innovation.

- Power of the Top Performers and LPs. Often, GPs claim that they would make more time for public purpose, if their LPs cared more and held them accountable. Some investors, particularly those with European LPs or with public pension investments, have been required to inc

- Increase their ESG and impact efforts over the last 2 years. Newer funds who are competing with other larger, top-performing venture funds on deals do not want to create friction in diligence by asking pressing questions to founders. When top-performing funds, especially those who lead rounds, do not ask tough futures-thinking or impact questions, smaller funds are less willing to do so for fear of losing their spot in a deal.

- Growth and Time. An area that lacks consensus is the timeline in which impact could realize. Some investors agree that the expectation of the elusive “hockey stick,” while being intentional about the impact or having thoughtful consideration of public purpose, does not always align. Investors do not seem to think there is a trade-off between overall return and purpose but, instead, it is about adjusting expectations on time. Some investors think that moving too fast and raising too much money is counter-intuitive to what is needed for impact or public purpose.

Analyzing Existing ESG and Impact Methodologies

For ESG or impact investors, frameworks help identify criteria and metrics that merit consideration. Some frameworks include methodologies for how to rank or score performance against these criteria and metrics. There are hundreds of frameworks, rating agencies and methodologies, ranging from those establishing high-level goals to those targeting a narrow component of public purpose such as climate. (See Appendix D for a non-exhaustive list of ESG and Impact tools, frameworks, startups and agencies.) The myriad of existing ESG organizations currently available can often be a source of confusion and divergence.14 Still, if used correctly and at the appropriate stage of a company, these resources can deliver value in holding corporations and their investors accountable. After analyzing more than 20 different investing frameworks, predominantly focused on ESG, we have identified several trends:

- Interconnectivity. Investors must recognize that a company’s impact resounds in its physical and virtual network, which extends to employees, contractors, customers, suppliers, investors and impacted communities, among other potential stakeholders. The Long-Term Stock Exchange (LTSE) directs companies to map their critical stakeholder groups and consider the role that they play in one another’s success. Several other frameworks—including GRI, SASB, the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) E&S Quality Score, and Sustainalytics—also emphasize the need to specifically report on suppliers’ management of issues around human rights, land use, biodiversity, social impact, child and forced labor, labor rights, environment performance and product safety.

- Long-term strategy. The strongest frameworks consider long-term impact. As a stock exchange, LTSE requires companies to report their policies for long-term value creation, including (1) consideration of a broader group of stakeholders and the critical role that they play in one another’s success; (2) measurement of success in years and decades and prioritization of long-term decision-making; (3) alignment of executive compensation and board compensation with long-term performance; (4) engagement with long-term shareholders; and (5) boards of directors’ engagement in and explicit oversight of long-term strategy. These reports help ensure high-quality growth capital and minimize stock-price volatility. Similarly, Integrated Reporting (IR) emphasizes the organization’s governance structure, the forward-looking risks and opportunities that might affect its ability to create value, and its resource allocation strategy for the long-term.

- Integrated reporting. ESG frameworks are continually redefining “profit” to reflect purpose and the associated values and costs of assets not encompassed in traditional corporate assets. They achieve this by producing integrated reporting structures that highlight the interconnectedness of financial performance and public purpose. IR, for instance, introduces a concept known as “the capitals’’ that incorporates a broad list of resources and relationships used and affected by an organization, including financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and natural capital. The components that generate these types of capital should be reported in a way that highlights their interconnectedness and ensures that the maximization of financial capital takes place hand-in-hand with—and not at the expense of—the other types of capital in the longer term.

- Industry- and sector-specific standards. Increasingly, ESG frameworks are adopting more sector-specific criteria, metrics and analyses. For example, SASB categorizes standards across 77 industries. Technology & Communications is separate from Food & Beverage, Health Care, Consumer Goods, and so forth. SASB further breaks out companies by sector within those industries; within Technology & Communications, SASB clusters companies by Hardware vs. Semiconductors vs. Internet Media & Services vs. Software & Services. By developing industry- and even sector-specific standards, frameworks can take into account the nuances of their respective companies. For example, SASB reports that Customer Privacy is likely to be a material issue for more than 50% of Internet Media & Services companies, but not for Semiconductor companies. These nuances are critical to effectively capture the shared value generated (or not generated) by companies.

- Emphasis on measurement. Newer ESG frameworks provide data-driven criteria and metrics, so that decision-makers can objectively measure effort, output and impact. Instead of relying on an organizations’ commitment to broad missions such as the SDG’s goal to “eradicate poverty,” investors can tangibly evaluate their performance through disclosures on how much workers are paid, how much they are provided in healthcare benefits and so forth. SASB offers clear technical protocols for how companies can report these metrics to standardize definitions, scope and accounting to allow comparisons across companies. MSCI ESG Ratings generates reports that rate/scale such metrics and enumerate levels of risk. These frameworks not only give companies the tools to incentivize positive action, but also standardize and quantify companies’ performance so that investors can compare them.

- Consistent reporting over time. It is essential to consistently consider companies’ performance in the context of public purpose over time. Businesses evolve, as do the social, political and environmental contexts in which they operate. As such, the definitions of, commitments to and influence on public purpose also evolve. Frequent measurement and reporting can not only help companies recalibrate their public purpose strategies, but also help investors gain an actual/historical view of a company’s standing on ESG issues. MSCI scores companies on their most recent quarterly performance, as well as on their 3-year historical record on managing risks and opportunities. While companies can map where they intend to move on certain issues, ESG standard reporting and measuring practices hold them accountable to such plans.

- A growing movement. Today, almost all frameworks are opt-in and self-reported, but their growing popularity is increasing reputational and social pressure for companies and investors to pay close attention to them. More investors, and even the general public, have been calling for companies to hold themselves to the standards that these frameworks provide. MSCI provides ESG ratings for more than 8,700 companies included in its regional and country indices. In 2020, 533 companies disclosed SASB metrics in their public company communications, up from 118 in 2019. With popularity comes proposed legislation. The UK Financial Conduct Authority has proposed a law that makes companies state whether their disclosures are consistent with Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) standards, and the European Commission recommends these disclosures. Similarly, the New Zealand Ministry for Environment has recently announced plans to make similar climate-related disclosures mandatory for certain public companies and financial institutions. Most recently, a coalition of more than 50 impact-oriented organizations, led by the U.S. Impact Investing Alliance and B Lab, called on the Biden-Harris Administration to create a White House initiative on inclusive economic growth.15

The amount of insight that these frameworks produce has been fostering the development of platforms like Metric,16Clarity AI,17Proof of Impact18 and Socialsuit,19 which are specifically invested in analyzing large data sets against ESG criteria in order to monitor and optimize organizations’ impact on people and the planet. However, existing ESG frameworks and their spillovers still fall short of covering crucial aspects of public purpose for some companies.

Summary of where ESG or impact frameworks fall short:

- Many ESG and impact frameworks fail to capture negative consequences or risks of technology-first companies.

- ESG is widely considered for public companies and large banks that have teams dedicated to their data and reporting. It is time-consuming for small startups to take on ongoing ESG metrics.

- For companies in early stages, some of the data requested for ESG reporting is not yet available.

- If a startup or investor considers ESG in their process, they are typically categorized as an impact investor to LPs and startups, which could impact their investor relations and deal flow.

- Generalist VC investors or those who do not invest under an explicit impact thesis want to be able to assess for negative possible outcomes to society without being referred to as an impact investor.

- When multiple investors in a round ask a startup for impact or ESG metrics, the requests across funds typically do not align and become a massive burden on a startup to complete varying requests.

- Financial materiality of impact or ESG is important but incredibly difficult to assess in the early stages when there is less emphasis on revenue and more emphasis on market size and growth.

- Startups typically make fast decisions and pivot on operations or business models, so what is measured in one quarter might not make sense in another, making it difficult to measure across time.

- New business models and products do not always fit perfectly into existing ESG or impact frameworks’ industries.

- ESG and impact have limited emphasis on economic drivers as they relate to growth, profitability, competitive advantage and liquidity.

- An overreliance on metrics takes away from the actual stories and scenarios, hiding some of the most consequential harms behind numbers and scores.

- ESG and impact metrics do not necessarily lead to structured conversations or considerations with VCs and startups; instead, the tools create benchmarks and are not integrated into diligence or planning.

- Existing frameworks and methodologies do not always allow for customized risk thresholds for companies or investors. For instance, a VC or startup might have more exposure to climate risks but is well equipped internally to address them.

VC + Public Purpose Indicator (VCPPI) as a Solution

The Venture Capital and Public Purpose Indicator is a tool that helps venture capitalists and early-stage startups assess their company and technology for public purpose, specifically around negative consequences. VCPPI will help VCs evaluate their portfolios to ensure startups are planning ahead for business and public risks related to the environment, labor & inequality, privacy & security, diversity & inclusion, governance & anti-corruption and long-term value creation. This tool can be used by generalist investors, in addition to impact investors.

The 3 sections to the Venture Capital and Public Purpose Indicator

- Score: Investors and startups analyze technology and company decision-making with pointed questions related to public purpose and business risks.

- Evaluate: Startups use a provided framework to evaluate stakeholders beyond customers and investors, with an emphasis on stakeholder access to power and resources and on how the technology impacts their lives.

- Simulate: Startups respond to scenarios related to public purpose to give an investor a sense of how the startup takes actions and makes decisions during tough situations.

VCs score the responses from the startups based upon their own risk and public purpose profile. The outcome of the tool is to show public purpose improvement over time and to create a checklist of items a VC and startup should discuss before, during, and after an investment.

If you are interested in a demo of the VC + Public Purpose Indicator, please visit our website.

VC + Public Purpose Themes from the VCPPI

Below are the 6 themes and corresponding questions we focused on for our research and the first section of the VCPPI tool.

Most of the questions that we ask below are qualitative and, given the nature of technology startups and their evolving models and decisions, these questions investigate decisions the CEOs have made in the past, how they are currently thinking about decisions and what their plans are for the future. Ideally, these questions would be customized depending on the type of technology and stage of a startup. The purpose of these questions is to anticipate decisions a startup may face and to allow VCs and startups to get on the same page regarding their public purpose intentions. We have provided reasoning, resources and additional reading for each of the sample questions.

Environment

Evaluates a startup’s effect on the world’s environmental issues, as well as that of the world’s environmental issues impact on a startup’s intended business model.

| Sample environmental questions for a VC to ask a startup | Why does this question matter? |

| What kind of resources or materials are you currently dependent on throughout your supply chain? What kind of materials could you become dependent on in the next 5 years? | Overexploitation of any materials and resources has long-lasting consequences on water supply, food, public health and risks of natural disasters. It also contributes to a decline in economic growth.20, 21 |

| How can executive, judicial and legislative climate-related regulations or international treaties impact your business model over the next 5-10 years? | Climate policy or regulation on a domestic and international scale can either provide ample opportunity for startups or impede growth and a startup’s plans to make money.22, 23 |

| How do the effects of climate change (water and food vulnerability, rising temperatures, sea level rise, extreme weather) affect your core business model now and in the future? | Startups may experience operational impacts from extreme weather to supply shortages. Startups can also be exposed to transition risks arising from responses to climate change, such as changes in technologies, markets and regulation.24 |

| Does your company directly impact a system related to climate (food, water, waste, energy)? If yes, is the system dysfunctional? Why or why not. | Fast-paced change related to urbanization or climate change generates uncertainty on already vulnerable systems. If a company directly impacts food, water, waste or energy infrastructure, one should ensure that it is in improving it, not making the system more vulnerable.25 |

| Where does your company stand on sustainability efforts relative to your competitors? | Having strong sustainability efforts can differentiate a startup’s strategy from their competitors, particularly if they are consumer-facing or in a market in which climate-related regulations are increasing.26 |

Labor and Inequality

Assesses how a startup creates sustainable jobs and provides a livable wage, reduces wealth and income inequality and provides dignified labor with benefits.

| Sample labor and inequality questions for a VC to ask a startup | Why does this question matter? |

| What percentage of your workers are full-time vs. part-time vs. contractors? | Being classified as either an employee or a contractor can determine whether workers have access to appropriate pay, benefits and protection from discrimination.27 Full investment in employees reduces turnover and possible legal battles. |

| Does your business model rely on low-wage or gig labor at any point in your supply chain? What percentage of your workers has access to paid time off, healthcare and other benefits? | Workers include gig, part-time, contractors and any other employees. In New York alone, earnings are so low for gig employees that 27 percent are covered by Medicaid, while 20 percent do not have any health insurance coverage. The occupational fatality rate for gig workers is over three times as great as it is for private payroll employees.28 |

| Does your company pay all workers, including part-time and contractors, a fair and livable wage ($16.54/hour) in the U.S.? | A living wage can be calculated by the MIT living wage calculator.29 Gig worker’s equivalent hourly wage is roughly at the 10th percentile of all wage and salary workers’ wages, earning less than what 90 percent of workers earn, with some studies showing 74% of Uber drivers, for example, earn less than the minimum wage in their state.30 |

| What is the possible impact that your company will have on existing job markets (domestic and international, skilled and unskilled, blue collar and white collar) over the next 10 years? What kind of work could be displaced by the company? | Innovation could lead to job growth, but could also displace industries. New tech, in concert with economic incentives, policy choices and institutional forces will alter the jobs available and the skills they demand. It’s important to understand how shifts in labor will impact companies and how innovation will shift labor.31 |

| Pre-COVID, what percentage of your workers were hired from the local economy in which you are located? | Increasing economic mobility in economically immobile cities or for underserved populations means creating opportunities (jobs, training, etc.) locally and adds to the overall economic growth of an area.32 |

Privacy and Security

Determines how much a startup centers privacy and security related to human rights, civil liberties and democracy in the development of their product and company.33

| Sample privacy and security questions for a VC to ask a startup | Why does this question matter? |

| Is any part of your company’s technology observing behaviors from any stakeholder? If yes, does the surveillance limit work autonomy, diminish well-being and/or limit workers’ and the public’s privacy? How are the stakeholders made aware of this observation? | Surveillance limits the opportunity to present oneself in the manner of one’s choosing. It is hence limiting on individual autonomy, impacting how individuals interact with the world. Constant observation also infringes on privacy, a dimension of one’s personality deserving positive protection.34 International human rights law frameworks should be applied to ensure that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are not infringed upon. Users who are being surveilled should be notified with enough time and information to enable them to challenge the surveillance decision or seek other remedies.35 |

| Which data/privacy policies (GDPR, HIPAA) currently impact your company? Are there other policies or norms that could impact the company, such as increased privacy laws in the U.S. or expected product disclosures? | HIPAA, CCPA and the broad adoption and enforcement of GDPR impact how some companies do business or develop models or products. With members of Congress releasing over 20 comprehensive information privacy bills or drafts, the U.S. will continue to debate privacy issues, and data companies should be aware of the operational and technical impacts of these bills.36 |

| Does your company use systems that make inferences and predictions about sensitive characteristics, behaviors and thoughts or rely on highly automated decision-making? If so, how is the company ensuring there are not mistaken results or reliance on profiling? | As of 2015, the outcomes of upward of 25 national elections in the world were being determined by Google’s search engine due, in part, to its predictive profiling.37 Predictive technology is typically biased against Black, Indigenous Peoples and People of Color.38 There needs to be clear governance for algorithmic transparency and accountability, allowing users to understand the overall system and to challenge any particular outcome.3940 |

| If collecting any data, does your company sell the data that you are collecting? If not, are there any plans to monetize data down the road? If yes, who are you selling the data to? | Large data collection can result in pricing discrimination, users remaining unaware of their data being sold to 3rd parties, not receiving compensation for their data and exploitation of marginalized communities.41 Users should be aware if their data is being collected and monetized, and they should have control of their data. Companies should publicly commit to the privacy of their users. |

| Does your company currently have an Access or Audit Log in place to track who has viewed any pieces of the company’s data? | Having detailed audit logs helps companies monitor data and keep track of potential security breaches or internal misuses of information. They help to ensure that users follow all documented protocols and also assist in preventing and tracking down fraud.42 |

Diversity and Inclusion

Helps a startup analyze the accessibility of their technology, in addition to assessing the internal decision-making that impacts recruiting and retaining diverse talent, while providing an inclusive environment that prioritizes mental health.

| Sample diversity and inclusion questions for a VC to ask a startup | Why does this question matter? |

| What is the demographic (ability/ age/race/gender/education level/etc.) breakdown of your company’s target customer or user? | Products should be used successfully by people of all different abilities, races, genders, ages and education levels. Building products with technology accessibility in mind provides access to larger markets and compliance with accessibility laws.43 |

| What practices does your company have in place to continue to evaluate product accessibility? | Staying current on testing methods and tools to test websites, software and electronic documents helps conform with the Revised 508 Standards.44 |

| Is there any difference between the end users and those people with buying power? | If a company has a customer that is different from its final user, it is necessary to understand and align the interests of all the buyers and users. What works for the customer (buying power) might not necessarily work for the person directly impacted (user) and could create harm. Understanding the difference can also lead to improved products.45 |

| Does your company engage in any internal or external initiatives to reduce discrimination, including initiatives for hiring and recruitment that consider age, race, gender, sexuality, ability, nationality, etc.? Does your company currently sponsor visas? | Based on survey results from more than 1,300 employees, almost half said that they would leave their current job for a more inclusive company (defined as embracing all people, making one feel valued and feel they belong in their organization).46 It is unlawful discrimination to require job applicants to have a particular citizenship status or immigration status. Employment opportunities should generally be available to all individuals who are authorized to work in the United States, including U.S. citizens, permanent residents, asylees, refugees and temporary residents.47 |

| Does your company provide resources for workers to ensure that they are prioritizing their mental health as it relates to depression, anxiety, substance abuse, mood disorders, etc.? | Nearly 1 in 5 US adults aged 18 or older (18.3%, or 44.7 million people) reported a mental illness in 2016. In addition, 71% of adults reported at least one symptom of stress, such as feeling overwhelmed or anxious. Workplace wellness programs can identify those at risk, connect them to treatment and put in place supports to help reduce and manage stress.48 |

Governance and Anti-Corruption

Understanding the evolution of startup governance over time and the complex stakeholders who often have overlapping and shifting roles on boards, while also minimizing corruption and undue market power.

| Sample Governance and Anti-Corruption questions for a VC to ask a startup | Why does this question matter? |

| How does your company externally influence the market that they are working within (participating in coalitions, lobbying, etc.)? | If policy impacts a business model, it is common for companies to participate in lobbying or PACs. Lobbying can lead to an increase in shareholder returns49 in the short run, but can also reduce overall economic growth and lead to monopolistic situations—reducing quality and increasing prices for customers.50 Pushing competitors out too early can also reduce the size of a market and impact fundraising or customer acquisition capabilities. |

| What is your company’s process if it discovers any unethical behavior (stealing, rule violation, lying, bribery, control, bullying, discrimination) from workers, founders and board members? | There are many frameworks to prevent fraud and corruption by the OECD, World Bank, ICC and more. Taking into account its structure and size, a company should have internal auditing controls and compliance programs to assist in preventing and detecting acts of corruption.51 |

| Do your company and board have any mechanisms to actively hear and incorporate feedback from internal and external stakeholders (employees, contractors, customers, shareholders, suppliers, investors, impacted communities, etc.) for both company building and product development? | Integrated external engagement (IEE) is increasingly a priority, with one study revealing that CEOs spend at least one-quarter of their time managing external engagement.52 External engagement needs to be part of everyday business decision-making, beyond corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts. For example, the Porter and Kramer “shared value” framework53 or Kramer’s “collective impact.”54 |

| Are there voting members of the board who are stakeholders beyond investors or founders? |

Given the significant influence that a company’s key stakeholders (community members, employees, unions, etc.) have on its future prospects, the board’s knowledge and understanding of the interests of those stakeholders should be among the factors that are considered when assessing the overall composition and balance of the board and whether there is a need to recruit new directors who represent those interests.55 |

| How does your company plan to incorporate its values and long-term vision into the board? | Race, gender and cognitive (behavior, opinions, experiences) diversity on boards lead to company improvement when there is a good culture in the boardroom.56 It is crucial to have strategic alignment on long-term vision and decision-making and its particular relation to performance and compensation. |

Long-Term Value Creation

Encourages a startup to think about real growth metrics, threats to a business and value creation for the general public and stakeholders beyond customers and investors, in a 10+ year timeframe.

| Sample long-term value creation questions for a VC to ask a startup | Why does this question matter? |

| Does the company displace any existing public sector functions? | The public sector is required to act in the public’s interest. If public sector services or products are privatized, it’s important to ensure that essential services remain affordable and available to large segments of the population.57 |

| If not already so, what will it take (growth models, time horizon, policy, etc.) for your company to become profitable? | Growth rates depend on a variety of factors: talent, capital requirements and the size, maturity and competition in the market. The market can punish premature or non-existent growth or over-inflated valuations and can cause quick collapses. Hard problems require patient capital and solutions, allowing for course corrections without total failure.58 |

| For employees who have left your company, how many purchased the vested options that they have not yet exercised? | Options reduce turnover during a vesting schedule, which reduces recruiting costs. Turnover is natural, with the Bureau of Statistics reporting that the average turnover rate in the U.S. is about 12% to 15% annually. A worker first-hand experiences the potential of the long-term success of a company. If former workers believe in a company’s long-term success, despite their departure, they are more likely to exercise their vested options.59 |

| Was the science or the technology at your company backed by university research, government grants or any other consortiums? | Cooperative efforts between academia, public and private sectors is essential for nascent markets and early business models. Researchers suggest and history illustrates that establishing cooperative research and development across the private sector, while ensuring that knowledge gained is leveraged by the broader scientific community, fosters long-term growth and scale.60 |

| If not already doing so, will your company ever give things away, or use a freemium business model in exchange for data? | Because freemium is a form of marketing and does not guarantee revenue, companies often have to sell the data that they are collecting to make up for lost revenue. The commodification of data and therefore privacy leads to concerns that might be a business model risk for such businesses and their long-term value creation: are they creating products for paying customers or free customers?61 |

Additional questions for each of these themes can be found in Appendix C.

The Importance of Stakeholder Analysis

Stakeholder analysis is the second section of our VCPPI tool. A stakeholder analysis is a process of systematically gathering and analyzing qualitative information to determine whose interests should be taken into account when developing and/or implementing technology. This is different from customer discovery or external engagement62 in that it analyzes who is impacted by the technology being created or deployed, not just purchasing or using. For this analysis, we recommend that early-stage companies consider current stakeholders, as well as ones they will potentially have in the immediate—from now to 5 years—and long-term—5 to 10+ years.

What is the purpose of this analysis?

Its purpose is to ensure that a startup has considered multiple perspectives, regardless of positions of decision-making or buying power. This analysis will help identify the communities or organizations that one should be considering or engaging with and to understand their position or influence on technology development, growth, reputation, regulation and overall harm.63

- Will the stakeholder push back or take action against your company?

- Will the stakeholder champion your company?

- How are the various stakeholders connected to each other?

- Does your company make the stakeholder’s life easier or harder?

- Does your company make the stakeholder’s financial situation better or worse?

- Does your company infringe upon the stakeholder’s human rights?

Some of this analysis can be collected through 3rd parties and research. Other times, the analysis requires engaging directly with communities in the form of community meetings, interviews, surveys, focus groups, etc.

“Building a strong connection with broad elements of society creates value, not least because it builds resilience into the business model. Compromising your connections with stakeholders simply to make earnings targets, on the other hand, destroys value. It’s the essence of short termism, measurably and overwhelmingly harmful to most shareholders’ economic interests. Research shows that firms that make significant investments for longer-term payoffs have future cash flows that are discounted less by investors than the cash flows of firms that allocate a smaller portion of their cash for the long term; immediate-minded fixes such as share repurchases (which arguably divert cash from investments that generate longer-term returns) correlate with increased discounting as well.”64

—Witold Henisz, Tim Koller, and Robin Nuttall

What is a stakeholder?

Any party or organization that interacts, buys, consumes or is impacted by the technology or company in question. The net impact of the technology or company can be either positive or negative, as well as either direct or indirect, to them. These stakeholders’ interactions with your company can be either intentional or accidental or unintentional. Stakeholders can and will evolve, and they have varying degrees of power and resources. They can be a company’s champion or opponent and, for that reason, it is always important to engage with them when appropriate.

On the VCPPI tool, we provided 8 initial stakeholder groups to consider. These suggested stakeholder groups are just the beginning! VCs and startups should consider other stakeholder groups, like environmental coalitions, and specific people or organizations within these groups.

- The Media: Can provide information and influence decisions.

- Regulators/Government: Can be local, state, federal or international. They can legislate, tax or regulate.

- Corporations: Can acquire, compete or dominate a market.

- Low-wage workers (not necessarily employed by the startup): Primarily service or retail workers. This group can be external or internal to your company. Can also be customers.

- High-skilled workers: Harder to replace and specialized in labor. This group can be external or internal to your company. Can also be customers.

- Paying customers: Has purchasing power and will exchange money for the product or service.

- Community groups: This includes groups such as unions, churches, hospitals and schools. Deep relationships, interests and concerns in the community.

- Marginalized groups: Marginalized in terms of disability, ethnicity, immigration status, gender, nationality, race, religion and sexual orientation. Commonly at risk of being discriminated against due to their identity, background or status.

Understanding power and resources

Stakeholders can persuade or influence a company. Their power may be derived from the nature of the stakeholder’s position, their connections or an abundance of resources. A stakeholder can have a lot of power over your technology, but not necessarily a lot of resources (e.g., low-income communities that protest the purchasing of a specific consumer product). Startups should rank stakeholders based on their perceived level of power to influence. Those with the least amount of power should be prioritized because they are typically the most vulnerable in society and can have the most to lose with disruption and technology. Power ranking is useful for assisting in decision-making situations in which various stakeholders have competing interests, resources are limited and stakeholder needs must be appropriately balanced.65

Engaging with the community

When you do not have experience with in-the-field engagement, how do you properly engage with stakeholders or communities? Appropriate community engagement requires planning, practice and a deep understanding of the community that you are hoping to engage with. As a first step, research other organizations—charitable groups, civic engagement groups, homeowner associations, organizing groups or anchor institutions such as faith-based organizations, hospitals and schools—that can act as intermediaries between your company and the community you are hoping to reach. Often these groups have meaningful relationships, have built trust and can facilitate connections or conversations if direct engagement is required. There are also organizations such as City Tech Collaborative and Public Sentiment, which helps decision-makers solve local problems using genuine community engagement fueled by local community networks and powerful digital tools.66 Lessons can be learned from how Sidewalk Labs failed to genuinely engage with multiple stakeholders in the immediate Toronto community during their Quayside project.67 Keep in mind that community engagement in these cases is not about customer acquisition or market research but about reducing harms and risks. If you are offered advice on how your startup or technology can impact a specific community, you should conduct additional research and seriously consider incorporating that feedback.

If you are interested in a demo of the Stakeholder Analysis on the VC + Public Purpose Indicator, please visit our website.

Startup Scenario Building and Responses

Scenario building helps develop an artificial plan based on a quick analysis and understanding of trends and events, illustrating the various paths that a startup can take. Every decision founders make at their company is a choice under a varying degree of uncertainty. These decisions can also have a major impact on the success of the company or the well-being of the general public.

In the third section of the VCPPI tool, startups are asked to respond to 3 randomly selected scenarios that are related to decisions a startup might have to make that overlap with public purpose considerations, answering the question, “What would you do?” We are looking for how startups would think on their feet in these difficult situations. We want startups to respond without overly scripted or overthought responses. These scenarios are hypothetical and there are no right or wrong answers. Responses should include a thought process and should be based on predictions about where the future is going. Helpful details in response include sharing how one would gather information to make a decision, as well as the actual method one would take to get to a final decision or response.

For each scenario, the responder will have 60 seconds to reply by recording a response on video. After the startup has recorded a response, the VC reviewer will be able to watch the playback of the video and offer suggestions or take notes for things to discuss in a follow-up.

Sample public purpose-related scenarios from the VCPPI tool:

- A junior member of your team discovers a data security breach at your company. What is your response over the next week?

- What is your immediate response if you hear your employees might unionize?

- If there is a downturn in the economy and your current investors temporarily pause investing, banks are lending less money and customers are spending less money, how do you react in the immediate moments to keep your company alive?

- Imagine local policy requires all companies to reduce their carbon footprint by 50%. What are ways your company could reduce its carbon footprint?

- If a major investor and member of your board want you to conduct your business in a way that goes against your values and mission, what are your first steps in working through the conflict?

If you are interested in a demo of the Scenario Builder on the VC + Public Purpose Indicator, please visit our website.

Public Purpose Integration in VC

Many investors and CEOs want to care and do more about how startups impact the public, but are not sure how. Generalist investors, impact investors and startups overwhelmingly signal interest to understand long-term public purpose.

The Theory: The obvious work is to figure out what a startup or fund stands for. At this point, you have your mission or values and the mandates that your LPs have laid out, but how do our 6 themes of public purpose (Environment, Labor & Inequality, Privacy & Security, Diversity and Inclusion, Governance & Anti-Corruption, Long-Term Value Creation) plug into your decision-making process? Any organization needs to figure out what its collective vision of the future looks like and how its technology or investments harmonize with that future. Some funds and startups will have a theory of change68 and others will just look for the next unicorns. What are the hard no’s (e.g., DoD contracts, freemium business models, water-intensive hardware, etc.)? Do the introspective work: what do you stand for and is it backed by research, science and not just personal values, patterns or gut instincts?

The Practice: For investors, there are plenty of ways to plug public purpose into your day-to-day operations. We have seen investors adjust their questions in diligence, build scenarios for startup founders to respond to and assist startups as they map their stakeholders during pre-investment considerations, during a pivot or rapid growth. These three practices were the inspiration for our VCPPI tool. Some funds make public purpose or impact explicit in their legal documents for pro-rata or follow-on considerations. VCs can also help startups think through their public purpose decision-making: addressing what needs to happen now, in the next 6 months or 12+ months and how to bring those decisions in OKR or goal-setting conversations. Investors can also learn alongside their startup founders by bringing in experts to provide workshops or lectures to their portfolio on topics such as ethical tech, human-centered design, human rights violations, data security, privacy, etc. Similarly, for extending education, there are over 50 books, academics, think tank papers, podcasts and pieces of government research that are referenced throughout this document. See Appendix F. The most influence and responsibility comes from the investors who take board seats. Startups and board members have a lot to worry, but centering public purpose in those boardroom conversations only minimizes risk to the company and the public.

We encourage startups and investors to use impact, ESG or public purpose tools that work for their process—whatever that might be. There is not one market-defined standard or process, and our VCPPI is just one tool that could be used. Doing research and figuring out which tool, framework and standards work best for your stage, a vision of the future, or theory of change is key.

For additional suggestions for VCs, please see The Startup Perspective: Business Case Studies.

For a non-exhaustive list of ESG and impact frameworks, please see Appendix D.

The Startup Perspective: Business Case Studies

To better understand the startups’ perspective on public purpose, ESG and impact, our team conducted a series of interviews with early-stage founders and CEOs. Their startups spanned from consumer marketplaces to robotics companies across industries like fintech, aerospace and urban mobility. We asked each of these companies questions about:

- The public purpose mission of the company

- How has your mission evolved?

- How do you ensure long-term alignment surrounding your mission with your stakeholders?

- How the company measures itself against that public purpose mission

- What metrics or benchmarks do you use to track your impact, if at all?

- If applicable, which frameworks do you employ to track these metrics? Do you audit these metrics externally?

- How the company considers negative consequences surrounding their public purpose

- Have you considered how potential changes in environmental regulations impact your long-term sustainability plan?

- Would you cease operations with a supplier if you discovered they follow unethical labor practices?

Given the influence investors can have on a startup, we derived several key areas in which VCs can positively contribute to their portfolio companies’ public purpose strategy:

- Take time to understand and state your expectations towards startups’ impact-focused missions and goals.

To get a better grounding of the startups, we started each of our interviews by asking about the company’s mission as it pertained to public purpose and how it has evolved.

In the cases where startups had already pivoted or gone through a change in their mission or impact area, that change was sometimes made as a “virtue signal” to potential investors. One of the startups we interviewed said that it was reviewing its mission statement to better reflect its broader ESG strategy because the startup believed that it would resonate with the series A investors it was targeting for the near future. Another startup, whose impact and mission included the “democratization” of the solution it developed, emphasized that the reference to democratization should be read in the commercial sense of making its solution widely affordable and accessible to a broader set of clients. Its pragmatic approach to a core part of its stated mission reflected investor expectations to “maximize profits and attract clients.”

VCs can help startups more meaningfully direct their impact towards benefitting the larger public or at least reducing harms. This takes a commitment to understanding a prospect or portfolio company’s current mission as it stands and to appreciate the space in which it operates. It also involves a clear, upfront message about what it is that a VC might expect and care about public purpose.

A great example of a VC understanding its startup’s mission: as one of the startups we spoke with pivoted to pursue a more climate-related purpose (a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions for customers in the hospitality space), one of their angel investors approached and suggested that the startup could also prioritize the reduction of other types of pollutants, beyond GHG emissions, that align with its business model and target customer segment. VCs should take time to understand the impact area of their startups and also help them refine what market opportunities there are in that space.

- Push for specific impact metrics tracking

Several of the startups, generalist or impact, that we spoke to did not have a comprehensive list of metrics that they measured and monitored pertaining to impact or public purpose. One company shared that, in advance of any fundraising, they ask investors for what types of metrics they would be most interested in seeing, and then tailored their pitch deck to highlight their performance in those areas. Another company argued that their public purpose could not be measured, as values cannot be assigned to the improved quality of life their service offers.

Similar to Point 1., if VCs could emphasize to their startups the importance of specific, ideally consistent impact or mission-related qualitative and quantitative tracking, then they could hold them (and startups could hold themselves) more accountable to the attainment of public purpose. It is also important for the various major investors, particularly on a board, to align early on how to prioritize metrics, so that a startup is consistent across their investors.

As startups grow, VCs can also point their startups in the direction of third parties to help develop and track these measurements. One startup that we interviewed onboarded an external resource and began to publish impact-related metrics to their board. The board was enthusiastic about this advanced reporting and, in other cases, could be the driving force behind it.

- Grow and share your network

Particularly at the earlier stages, a startup’s network is limited to the founders’ social and professional networks. Consequently, many early-stage boards lack meaningful diversity—in terms of gender, race, experience, education, investment status or ethnicity. One startup that we spoke with noted their glaringly homogenous older, white, male board. When asked about its curation, the founder noted that their advisors accumulated by personal relationships. They said that they are actively searching for people of color and women to join their advisory board, but fault their limited success in finding these people as a consequence of their small size.

VCs can and should leverage their extensive networks to increase diversity on startups’ advisory boards. To expand the depth and breadth of their own networks, investors should be intentional in actively seeking out diverse perspectives, new organizations to engage with and different spaces to be part of, dropping their over-reliance on their existing circles. One startup noted with pride their intentionally diverse investor base—40% women, and a notable number of people of color. They acknowledged that this intentionality around (and access to) diverse investors came from one of their early VCs, who proactively made numerous introductions on behalf of the startup’s founder.

- Conduct scenario-planning exercises with your portfolio

Most founders became defensive or evasive when we asked them to consider external or internal low-likelihood high-impact events that could put their companies or entire industries on the verge of an existential threat and test the limits of their real commitment to public purpose. Those events oftentimes included new federal law or new regulations impacting the core of the businesses, the realization that their technologies or services could be exploited by customers or other stakeholders to cause harm or abuse and newly surfaced environmental neglect found in the supply chain, among other negative or unintended consequences.

Most startups seemed off-guard when questioned about their preparedness to deal with such events. One of the interviewees evaded these questions altogether and simply referred to their company’s growth strategy. Another said that the biggest negative consequences on their radar were “fraud and larger competitors,” although our analysis indicated that the startup should be elevating human rights and data privacy considerations. Yet another emphasized how their company complied with existing laws and called for governmental action to prevent certain risks to their business.

With some notable exceptions, few founders seemed to have thought deeply about how to adequately prepare for future public purpose-related events that stress-test their impact on the public. This is an additional area where VCs could help provide startups with the space to consider these longer-term consequences through intentional, structured scenario-building and conversations. Startups, particularly at the early stages, might lack the capacity to consider impact beyond the short-term; however, it is essential to do so in order to strengthen strategic planning and reduce future risk. Our VCPPI tool provides a mechanism to facilitate some of those conversations.

Defining Success by Preventing Risk and Harm

On top of all of the things a startup needs to worry about, particularly in the early stages—product, investors, customers, talent, cash flow, growth, mental health and more—public purpose could seem daunting when time capacity is a reality. The unknown is also intimidating as startups pivot and make new changes daily. But startups and VCs should make time for the things that matter, and public purpose in venture-backed startups matters. Investors and startup founders should work together to consider, on an ongoing basis, difficult decisions and risks, as well as how they impact not only business models, growth, product-market fit, regulation and talent, but also negative consequences on the general public. Doing so early will save time in the long run.

If VCs and startups considered public purpose in diligence, what could we prevent?

“I’m pretty sure I had or still have COVID-19, and I self-isolated the moment I started having symptoms. My children have had it as well. I immediately contacted Lyft to let them know that I would be returning my rental and isolating. I then contacted them to see what relief would be available to me. They indicated that without a positive test result, I get no help. But no one can get tested in Colorado unless they are admitted to the hospital or meet the criteria for high risk. I contacted my primary care physician, and they indicated they would not issue a request for a test because I do not meet the criteria. I’m convinced Lyft knows that not many people can get tested so they made that a requirement for helping drivers, thus limiting their need to help drivers. This is a crock of shit. I have been driving full-time for Lyft for a year with over 3,900 rides. I would estimate Lyft has made in excess of $40,000 from me. Still, they can’t help me even though I did the right thing and stopped driving.”69

Without government or market standards for VC-backed startups, we hope VCs and startups anticipate technological and company-building harms with our research and VCPPI tool. We want VCs to take responsibility for the outcomes of their investments, not just their returns. We want to help startups realize the importance of privacy and security and how they relate to human rights and civil liberties before they infringe upon them. We want to encourage startups, regardless of their mission, to mitigate climate change as early as possible. We hope generalist investors and startups alike will prioritize labor issues and provide dignified work for the highly educated engineers and the low-wage workers who keep the “machines” running. We hope that startups and investors will get serious about recruiting diverse talent and prioritizing their well-being. We hope to guide startups and VCs as they create processes early on to prevent corruption and ethical issues. We want to help reduce economic inequality and motivate innovators to think about long-term value creation for all, not just a few.

Appendices

Appendix A - Frequently Asked Questions

What is meant by “negative consequences”?

Also known as unanticipated consequences or negative externalities, are outcomes of purposeful action that create harm or risk to the public or company. This is the opposite of intended positive impact where the action results in a measurable and foreseeable harm reducer or benefit to the public. Examples of negative consequences include deep fakes, news misinformation, labor lawsuits, or depleting natural disasters.

What evidence do you have that these are the right areas to be focusing on?

We have used social scientific evidence, analyzed business cases, and applied theories from economists and political scientists to prioritize the questions being asked. For more information on our references in Appendix F.

Is the Public Purpose Indicator tool supposed to replace other frameworks or methodologies?

No. We don’t think there is one framework, organization, or methodology on the market that covers all bases. This tool is to be used alongside existing forms of diligence. This tool would also work for investors who do not measure impact or ESG and want to start to consider public purpose.

Where did the idea of VC + Public Purpose come from?

Despite having a business degree, TAPP Fellow, Liz Sisson, has worked most of her career in government and policy before joining the Urban Us venture team in 2017. She often approached investing like a policy process. She considered stakeholders outside of customers and investors and thought about the long-term impact the startups in the Urban Us portfolio could have on inequality, labor, privacy, and the environment. She wanted to scale that type of public purpose and educate other investors on the impact (both negative and positive) that investments could have.

Appendix B - Definitions for Frequently Used Public Purpose Terms

- Impact Investing: Impact investments are investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. Impact investments can be made in both emerging and developed markets, and target a range of returns from below market to market rate, depending on investors’ strategic goals.70

- Corporate Social Responsibility: A management concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and interactions with their stakeholders. CSR can be philanthropy, charity, volunteer, donations, or ESG practices.

- ESG: ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance. Investors are increasingly applying these non-financial factors as part of their analysis process to identify material risks and growth opportunities. ESG metrics are not commonly part of mandatory financial reporting, though companies who are interested in CSR are increasingly making disclosures in their annual report or in a standalone sustainability report.71

- Shared Value: Policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates. Shared value creation focuses on identifying and expanding the connections between societal and economic progress.72

- B-corporations: Certified B Corporations are businesses that meet the highest standards of verified social and environmental performance, public transparency, and legal accountability to balance profit and purpose.73

- Social Responsibility/ISO 26000: International standards on an organization’s performance on their commitment to the welfare of society and the environment.74

- Conscious Capitalism: An economic philosophy with four specific tenets—higher purpose, stakeholder integration, conscious leadership, and conscious culture and management—to build strong businesses and help advance capitalism further toward realizing its highest potential.75

- Compassionate Capitalism: This means that corporations account for the risks they impose on the environment, the communities that interact with their company, office, or factories and treating their employees with more kindness.

- Stakeholder Capitalism: A form of capitalism in which companies seek long-term value creation by taking into account the needs of all their stakeholders, and society at large

- Public Interest Technology: Adopts best practices in human-centered design, product development, process re-engineering, and data science to solve public problems in an inclusive, iterative manner—continuously learning, improving, and aiming to deliver better outcomes to the public.76

- Responsible Technology: Refers to the versatile, multidisciplinary field that aims to better align the development and deployment of digital technologies with individual and societal values and expectations.77

Appendix C - Additional Questions for Diligence

Additional public purpose-related questions an investor could ask startups in diligence.

Environment

- How scarce are the natural resources being used today?

- Do any of the environmental considerations increase costs for the startup?

- Does the startup/technology directly purchase or rely on outside parties to purchase supplies and goods?

- Are there environmental considerations for who the startup/company’s future vendors or partners might be?

- Does the startup/technology know the sustainability efforts of their current cloud provider or data center?

- Is the startup carbon-neutral? If not, are there plans to become carbon-neutral?

Labor & Inequality

- Can your company operate without relying on low-wage workers?

- Are the workers of the startup’s suppliers or retailers paid a fair and livable wage?

- Does the company provide skilling or upskilling programs for workers and/or the immediate community?

- Is the CEO paid (salary and bonus and shares) less than 7x than the lowest paid worker?

- Do you plan on sharing equity with your lowest level employees?

Privacy & Security

- What type of disclosures are legally or culturally expected for the product?

- How much transparency and control is offered to customers or any other stakeholders when it comes to the observation of their behaviors or processing of their data?

- Could this startup be used to restrict speech?

- Can the customer’s end users manipulate or use the product in a harmful way?

- Does this technology manipulate or control human behavior or have any associated threats to human dignity, agency, and collective democracy?

- Does this technology use systems which make inferences and predictions about sensitive characteristics, behaviors and thoughts?

- Are any parts of this product enabling war, violence, divisiveness, bias, misinformation or hateful behavior? If yes, what is your plan to prevent this?

- Does this product require content moderation? If so, who will moderate?

- Does the company buy data or in any way use data brokers’ services?

- Does the company extend more careful privacy and security standards even for geographic areas that may not yet have legislation on those issues?

- Does the company have a product liability policy?

- How large is the startup’s IT team? Has the IT team grown in proportion to other departments?

- How many data breaches have been identified at the startup?

- How often has the startup conducted an internal audit of its security measures in the last 12 months?

Diversity and Inclusion

- Think about the last five people to leave your organization. Do you notice any commonality in their circumstances or background of their departure?

- What is the demographic breakdown of end users and customers (if they are not the same)?