This article is republished from the Arctic Yearbook 2023 under a Creative Commons license.

Abstract

Since the end of the Cold War, the Arctic has been defined by Arctic scholars as “exceptional.” A region protected from geopolitical tensions to the south. However, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent pause of circumpolar cooperation have challenged this designation. The Arctic appears to be again dominated by geopolitics. This article seeks to see beyond conventional understandings of “Arctic exceptionalism,” acknowledge a broader range of characteristics and features that make the Arctic unique and consider how this expanded view alters our perceptions of the region’s governance. Constructed as a thought experiment, this article asks, “what makes the Arctic exceptional?” And, by extension, “how does this allow us to see the Arctic and its governance differently?” To answer these questions, we introduce three stories of the Arctic as defined through geopolitics, environment, and Gwich’in homelands. What insights do these stories provide about the past, present and future of the Arctic and Arctic governance? In a time of rapid change, uncertainty about the future, and reckoning with the past, it is important to examine assumptions, challenge the status quo, and continue to foster governance innovation. This article seeks to contribute to this effort.

Introduction

‘Arctic Exceptionalism’ is a concept that has been used to describe the Arctic as a unique region that enjoys a “level of immunity to many of the world’s geopolitical problems” (Murkowski, 2021). Therefore, it is not surprising that the freezing of Arctic cooperation following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has generated headlines announcing the death of Arctic exceptionalism (Exner-Pirot, 2023), or arguing that it never really existed (Melchiorre, 2022; J. Smith, 2022). However, Arctic experts often remind us that there are many Arctics (Dodds & Smith, 2022; Łuszczuk, 2017). In this article, we argue that Arctic scholars should be open to the idea that there are multiple features, beyond geopolitical dynamics, that have made and may continue to make this region exceptional.

During this time of rapid change, uncertainty about the future, and reckoning with the past, there is an opportunity to critically examine mainstream assumptions, challenge the status quo, and foster further governance innovation. To contribute to this effort, this article asks: “What makes the Arctic exceptional?” We, the authors, seek to challenge mainstream discourses about the Arctic and its governance. Constructed as a thought experiment, we introduce the stories of Arctic geopolitics, environment, and Gwich’in homelands to expose different narratives regarding what defines the Arctic and what makes the region and its governance exceptional. Each story examines the Arctic from a different position that draws on the expertise, knowledge, and experience of the authors.

We begin with the geopolitical story of the Arctic because this is commonly where mainstream discussions about its exceptionalism are focused. We map out the evolving narrative of how states have interacted in the region and how they have defined the Arctic as a region. We then examine the relationship between the geopolitical story of the Arctic and the conventional narrative of Arctic exceptionalism. Next, we introduce the environmental story of the Arctic. In contrast to the firm lines drawn in the region by states, this story outlines multiple, dynamic boundaries that have been used to define the Arctic. Through this story, we demonstrate that Arctic exceptionalism has characteristics that extend beyond geopolitics, emphasizing dynamic connections within and beyond the region. Finally, we present the Gwich’in story. This story shares a deep, intimate connection with place. It brings to life elements of Arctic exceptionalism that are often referenced, but perhaps still under-appreciated – how the engagement of Arctic Indigenous Peoples in the governance of this region is at the heart of Arctic exceptionalism.

Following the presentation of each story, we revisit the idea of Arctic exceptionalism. We consider how these three stories, brought together, provide an expanded and richer understanding of what makes the Arctic exceptional. We go on to consider how this expanded view may provide new insights about the form and function of Arctic governance in the face of significant geopolitical, environmental, and socio-economic changes.

The delivery of these stories may be uncomfortable for the reader. When we started, we attempted to find a common voice for the entire article. But we realized that in writing, as in practice, each story has its own language, style, and tone. We wanted to respect that. We wanted to allow the narrative of each story to be present in this article as it is in the interactions of Indigenous Peoples, policymakers, and researchers within the Arctic Council, and other institutions in the region, where widely different perspectives are shared and reconciled. We came to understand that sitting with this discomfort provides an opportunity to learn and challenge our assumptions. It is an opportunity for growth and new ways of thinking (Boudreau Morris, 2017; Natanel, 2022). We invite you to experience the value (and discomfort) of bringing these stories together and to explore their points of harmony and discord.

Geopolitical Story: The Conventional Exceptionalism Narrative

In the most simplistic and classical terms, geopolitics focuses our attention on the interests and power of states combined with the strategic value and control of physical territories and space (Dodds, 2019; Heininen, 2018). In these terms, we see global affairs as the interplay of states and observe distinct stages in how the Arctic has been positioned in the world and how the region has been governed. In recent history, the mainstream perception of the region has evolved from that of a remote, unclaimed space of discovery and competition between colonial states, to a strategic military theater of great powers, to an exceptional space of peace and cooperation, to the contemporary reemergence of competition and tension. Each of these geopolitical realities has involved different governance architectures, but all have assumed that the primary actors are states.

Emergence of Arctic as a Region

The name “Arctic” originates from the Greek arktos, or bear, because of its proximity to the constellations Ursa Major and Ursa Minor in the northern sky (Liddell & Scott, n.d.), but the idea of the Arctic as a region came into being quite recently. European exploration of the Far North began as early as the 16th century as a quest for natural resources, in particular Dutch whaling and hunting of seals and walruses. The rush of southern explorers to discover shipping routes to and across the North Pole began in earnest in the 19th and early 20th century. These celebrated expeditions to the Far North told Europeans a misleading story of the Arctic as empty, devoid of sovereign actors, and undefined in geopolitical terms: Terra Nullius, like a blank spot on the map (Labévière & Thual, 2008: 17). According to the principles of international law at that time, that blank spot was up for grabs.

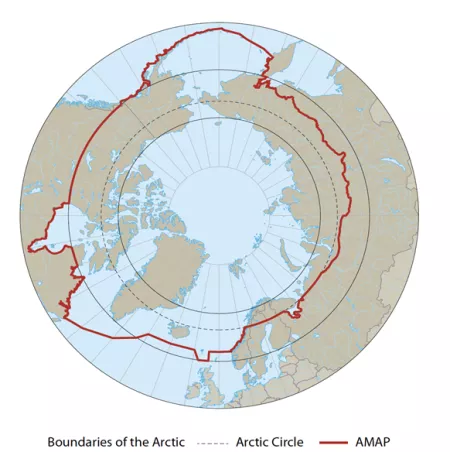

As states claimed land and established boundaries, they saw these northern spaces primarily as vast resource hinterlands or a remote military theater. As early as World War I, the Far North was militarized in support of southern states and their conflicts. World War II saw major investments in military infrastructure in the North, and with the Cold War the Far North became a frontline for great power competition. The emergence of the Arctic as a region in its current form can be linked to efforts to end the Cold War. Many diverse efforts to reduce tensions and demilitarize the Far North culminated in a well-known 1987 speech by Mikhail Gorbachev in Murmansk that evoked a vision of a peaceful Arctic (Gorbachev, 1987). This created an opening for the first initiatives to establish the Arctic as a cooperative governance space: first, the International Arctic Science Committee in 1990, followed by the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy in 1991, and then in 1996 the Arctic Council (English, 2013; Koivurova, 2010; Rogne, 2015; Watt-Cloutier, 2015; Young, 2013; Huebert, 2017). Through these new institutions, the “Arctic States” were defined to include Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, and the United States (Figure 1).

In the early 1990s, the establishment of the Arctic Council, with its broader mandate than previous Arctic institutions, was not a certainty. The Inuit and Sami had been championing their involvement in transboundary Arctic institutions for some time and had been frustrated by the limited success they had achieved in the creation of the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy, where they were offered observer status (Axworthy & Dean, 2013; Watt-Cloutier, 2015). In negotiations to create the Arctic Council, Canada was spurred by Indigenous activists and their allies in civil society to champion establishing a more substantive role for Arctic Indigenous Peoples (Axworthy & Dean, 2013). The other Arctic states were less comfortable with this proposition, slowing efforts to launch the Arctic Council (English, 2013). After extensive negotiations, the unique category of “Permanent Participant” was “created to provide for active participation and full consultation with the Arctic indigenous representatives within the Arctic Council” (Arctic Council, 1996).

The U.S. was staunchly opposed to the inclusion of hard security issues on the Arctic Council agenda and proposed a footnote in the Council’s founding declaration that stated: “The Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security” (Arctic Council, 1996). Despite the aspirations and lobbying of peace activists, hard security issues were taken off the table (Axworthy & Dean, 2013; English, 2013).

Recognizing the Arctic as a Unit of Governance

With the establishment and acceptance of several circumpolar institutions, the Arctic was legitimized as a unit of governance and the groundwork was laid to position the region as an innovative “zone of peace and cooperation” along the lines of the vision articulated by Gorbachev. Arctic states generally handled affairs in the region as uniquely insulated from tensions to the south. The norm was established that the primary institutions governing the region would work around hard security issues and geopolitical concerns. In this way, rather than serving as a frontline between great powers, Arctic states joined forces to protect and celebrate the Arctic as a unique - and exceptional - governance space (Nord, 2016).

Supranational governance is shaped by layers of international, regional, and national laws and policies. The boundaries of the Arctic and the authority of the eight Arctic states to govern the region work within, and need to be aligned with, this complex multi-level governance regime that recognizes the Arctic states as the central decision-maker in regional affairs (Byers, 2009). Nested within this international regime, the Arctic Council emerged, or has been positioned, as the preeminent decision-making forum for the region (Arctic Council, 2016). The elevation of the Arctic Council as the stage for Arctic decision-making has served to reinforce the boundaries of the Arctic as a region and, by extension, to legitimize the Arctic states as its primary decision-makers. This, in turn, has made the Arctic Council even more valuable to the Arctic states as a means of confirming their role in the region.

In the 1990s, the formation of the Arctic as a unit of governance and the positioning of Arctic states as the legitimate decision-makers for the region did not attract much attention from the capitals of Arctic states, let alone from actors further afield. The establishment of the Arctic Council in 1996 was relatively low key and expectations were limited (English, 2013). In the first decade of its existence, the Arctic Council gained credibility for its high-quality scientific assessments and policy advice (Platjouw et al., 2018; Steindal et al., 2021), but the Council and the region remained primarily below the political radar. It was only in the late 2000s and early 2010s that the Arctic began to gain more global prominence. Scientists and activists started to sound the alarm that the Arctic was a harbinger of climate change (Watt-Cloutier, 2015), and states and business took an interest in the region as a last frontier for untapped natural resources (Dodds, 2010; Heininen, 2005) and a space for potential new shipping routes made accessible by climate change (L. C. Smith & Stephenson, 2013). This increased interest translated into new mainstream narratives of competition and a race for resources in the Arctic (Spence, 2017).

The first notable response to this increased global interest was the release of the Ilulissat Declaration by the five Arctic littoral states (Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, United States) in 2008, which pointed to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as the appropriate framework that defines the maritime boundaries within the region, contributes to substantiating the authority of the Arctic states to govern the region, and “provides a solid foundation for responsible management by the five coastal states and other users of this Ocean” (Ilulissat Declaration, 2008: 1–2).

Efforts to reinforce this are evident in revisions to the Arctic Council Rules of Procedure in 2013, which introduced new criteria for admitting observers that included:

“b. recognizes Arctic States’ sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the Arctic;

c. recognizes that an extensive legal framework applies to the Arctic Ocean including, notably, the Law of the Sea, and that this framework provides a solid foundation for responsible management of this ocean" (Arctic Council, 2013: 14).

Despite these new requirements, the number of non-Arctic state Observers in the Arctic Council doubled in 2013 from six to twelve, which suggests that the Arctic as a unit of governance and the Arctic Council as a forum for the governance of the region were being recognized as legitimate and important.

A Belief in Arctic Exceptionalism

As the Arctic took shape as a region, so did the narrative of the region as an exceptional governance space. Mikhail Gorbachev’s vision of the Arctic as a zone of peace is recalled regularly by Arctic scholars and officials. Since 2011, all Arctic Council declarations and statements have opened with a commitment by Arctic states to “maintain peace, stability and constructive cooperation in the Arctic.” Despite tensions between Russia and the West in other parts of the world, there appears to have been an agreed norm amongst the eight Arctic states that the Arctic could and should be protected as a space for peaceful and constructive dialogue and cooperation. This exceptionalism was put to the test with Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014. Many speculated that the Arctic as a zone of peace could not be maintained with rising tensions to the South. Instead, the ability of Arctic states to successfully sustain peaceful dialogue and cooperation in the region following the invasion of Crimea amplified the narrative of Arctic exceptionalism. In fact, the case became so compelling that the Arctic Council was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2022 (before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) for its ability to maintain peace and stability while navigating dramatic environmental and geopolitical changes in the region (Wenger, 2020; Jonassen, 2022).

Ultimately, the Arctic exceptionalism narrative was challenged by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The spillover effects were evident in the pause of many bilateral and multilateral efforts and activities that involved Russia, including under the Arctic Council. On 3 March 2022, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the United States released a joint statement announcing they were “temporarily pausing participation” in the meetings of the Arctic Council (U.S. Department of State, 2022). Since that time, despite various efforts to emphasize the value and importance of continuing Arctic cooperation, the prospects of “business as usual” in the Arctic Council have been rejected by many officials and experts (Savage, 2023). Because of the disruption of cooperation in the Arctic as a result of events outside of the Arctic, Arctic scholars have called into question the Arctic exceptionalism that has been celebrated for over two decades.

This story centered around the conventional definition of the Arctic as a geopolitical region, categorized as exceptional in terms of the interests and actions of states. We have mapped out the conventional Arctic exceptionalism narrative. It frames the question, can the Arctic remain exceptional - indeed, is it still the Arctic - when it is no longer governed as a cohesive unit? Can the Arctic remain the (exceptional) Arctic without the participation of Russia? The following environmental and Gwich’in stories challenge us to expand our thinking, add to our understanding of Arctic exceptionalism and, by extension, consider alternative ways to see and explore Arctic governance.

Environmental Story: Narrative of Unique Ecosystems, Unprecedented Changes, Global Repercussions

We have considered in some detail the geopolitical events that led to the creation of the Arctic as a region, but the boundaries of the Arctic are generally assumed to be linked to certain physical and/or geographic parameters. In this section, we examine how the Arctic is defined environmentally, the physical and ecological traits of the region that make it exceptional, and what this means for the governance of the Arctic.

Environmental Boundaries of the Arctic

While the Greeks defined the Arctic using the night sky, more precise definitions have been used since. In general, these definitions fall into two categories. The first is defined by a geographical border, for instance the geographical area north of the Arctic Circle, the southernmost latitude where the sun does not set on summer solstice and does not rise on winter solstice, currently at 66°33′49.5″ north of the Equator. An alternative geographical definition of the Arctic has been the whole or parts of the states lying north of the polar circle, as done by the Arctic Council (AMAP) (Figure 2).

In the second category, the Arctic is defined by physical or biological traits. One of the most common of these is the 10 degrees Celsius isotherm, the southernmost area where the average temperature for the warmest month is below 10 degrees Celsius (Daubmire, 1954: 19-136). As a consequence, the temperature sets the extent or distribution of other characteristics of the Arctic. One such characteristic of the Arctic marine environment is the sea ice extent, where the permanent ice definition is based on the seasonal minimum extent, usually in September. The seasonal ice is defined based on the maximum in May, while the marginal ice zone is where the ice meets the open water, defined as areas between the dense drift ice and open water where the density of sea ice is between fifteen and eighty percent (Norwegian Polar Institute, n.d.; Strong et al., 2017; National Snow and Ice Data Center, n.d.).

For land based areas, the Arctic is often defined into different bioclimatic zones (e.g. artsdatabanken's "Bioclimatic Zones in the Arctic" [in Norwegian]). The Sub-Arctic zone is the transition zone between the tree line and the boreal forests. The tree line, usually aligned with the 10 degrees Celsius isotherm for July, is defined as the border between Sub-Arctic and Low Arctic, while High Arctic is distinguished from Low Arctic by having no woody shrubs of any kind.

Frozen soil called permafrost is a feature common for large parts of the Arctic. For both land and sub-sea ground, permafrost is a characteristic defined as ground (soil or rock and included ice or organic material) that remains at or below 0°C for at least two consecutive years (Osterkamp & Burn, 2002).

For most of the definitions in this second category, the Arctic has unique features. While the Arctic has similarities with the Antarctic or High Alpine areas when it comes to physical parameters like temperature or permafrost it distinguishes itself by being an ocean surrounded by continents. Likewise, the wildlife and ecosystems are unique, where a large portion of the more than 21,000 species found are endemic to the Arctic (Arctic Council, 2013) several which have no areas for further displacement.

Arctic Environmental Exceptionalism

The Arctic has conventionally been viewed as a pristine environment, distanced from industrial development and impacts. However, the Arctic ecosystem is not isolated from the lower latitudes and is now recognized as a hotspot for rapid changes influenced by anthropogenic emissions further south (Rødven & Wilson, 2021). Even definitions of the Arctic that are generally assumed to be static are changing: The radius of the Arctic circle currently shrinks annually by approximately 15 meters, due to the angulation of the planetary orbit (Tanner, 2023). Still, this is considered stable compared to the immense change of physical and biological parameters characterizing the Arctic. Since 1971, the average surface temperature of the Arctic has increased by an average 3.1 degrees, which is about three times as fast as the global mean (AMAP, 2021). The precipitation has increased by 9%, but with a 24% increase as rain. This has led to dramatic changes of the Arctic; since 1979 the sea ice extent has almost halved, and land fast ice, in particular the Greenland ice sheet, has decreased dramatically. The soil temperature has increased since 1971 by 2-3 degrees Celsius, leading to thawing of permafrost. This has again led to massive shifts in ecosystems, where more southern marine, terrestrial, and avian species have moved northwards (AMAP, 2021). Arctic marine species in the Barents Sea are being replaced by Atlantic species, which again has changed ecosystem functions and stability (Kortsch, Primicerio, Fossheim, Dolgov, & Aschan, 2015; Fossheim, Primicerio, Johannesen, Ingvaldsen, Aschan, & Dolgov, 2015).

In general, physical and ecological traits and processes that dominated and defined the area known as the Arctic have been challenged, and partly replaced, by traits and processes usually defining areas at lower latitudes. Would this challenge mainstream beliefs in the exceptionalism of the Arctic environments, and where does it lead to in defining stakeholders and setting conditions for decision making?

From an environmental perspective, Arctic exceptionalism could be defined with regards to the exclusive features of the Arctic environment, like exclusive Arctic ecosystems, or the remoteness to sources of pollution and other anthropogenic influences. This has also spilled over to management regimes, where the rareness due to Arctic conditions has set the value of protection. For instance, Arctic species are of particular importance for protection as they do not exist elsewhere and have no other potential refugia to migrate to. In other words, a value for protection by the exclusiveness or exceptionalism of species or ecosystems. However, connecting environmental management to such exceptional features is a two-edged sword: in a changing world the displacement of Arctic ecosystems northwards may also devalue the southern margin of such systems as they lose their exclusiveness and transform into near-Arctic ecosystems. Will the Arctic remain exceptional if its ecosystems transform?

Gwich’in Story: Narrative of Homelands and Resilience

Even though almost forty years have passed, I remember vividly the first time I saw lightning in the Arctic: the forking flash igniting the blackened sky and the earth rumbling boom, the power unleashed. The sky exploded over and over in flashing light and sound and the rain pelted the ground with force. The summer darkness, the crack and boom of the flash, was so strange to all of us kids so used to the midnight sun which would roll around and around at the edge of the sky, a yellow ball kicked to the end of its tether and circling. In the dark day of the first lightning storm, we went to our elevated cache and pulled out our caribou skin sleeping rolls and wrapped them around ourselves and sat out in the pouring rain to watch the lightning and feel the rain. The Arctic was still the Arctic then, but in those flashes, and we didn’t know it at the time, a destructive future roared to life.

I grew up in Fort Yukon, Alaska, and I can still remember my father, who was the Chief of our Gwich’in community when I grew up, explaining to me that “all engines need three things to run: fuel, air, and a spark. If you’re having problems, start there in those three places first.” He showed where the motor got fuel, where it got air, and where its spark came from. He would often talk like this, not just about things or parts, but about the relationships of things, and how things thrived. He would say "everything is alive,” “we were born into paradise right here,” “it’s not enough to do the right thing, no, we even need to think right, think right about the world, because it doesn’t, our thoughts don’t end with our skull, okay?” I remember once he had to prove that he was using some land in order to file a claim for it from the government, and the agent walked around and said, “I don’t see any sign of habitation here.” My father insisted that we used that land every spring for trapping, and finally the government agent found a tea kettle hanging in a tree and said “Ah! Evidence!” My father was so embarrassed about this evidence, proof that he had been there, but the government viewed this as critical to showing that the land was being used “correctly.” It’s interesting how two people can draw such radically different conclusions from the same tea kettle.

One day I was splitting wood in the yard, when I was about ten, the pile was long and high, about twenty-five feet long and four feet high, all of which needed to be split for the coming winter. I enjoyed it, the crack and split, knowing that a warm fire would result. An Elder, Sammy Roberts, used to tell me when he saw me, “Ah Eddie, some people they were complaining that they were getting cold, you don’t get cold eh? No, hard workers they never get cold.” As stick after stick split, a stranger walked into the yard, a white man, and it was unusual to see a white stranger in our remote fly-in only village back in those days. He came to talk with my father and as I split the wood I listened and remembered their discussion: “Hello Clarence, so I wanted to conduct an interview with you and ask you about climate change. Do you think that’s real, and have you seen any effects of it?” It was the mid 1980’s, and apparently this was controversial where the man was from, and I remember my father narrowed his eyes a little bit and looked around and said “Sure, it’s everywhere. Look around, absolutely everywhere.” The man thought he was talking to someone who was misinformed, and he said “well, I don’t see it, what do you mean?” My father pointed to one of the blocks of wood that I was chopping, “Well, what do you see?”

“I see a block of wood.”

“No, I didn’t ask you what it was, I know it’s a block of wood, I cut it, I said what do you see?”

“I don’t know what you mean. I see a block of wood, it’s spruce I guess.”

“No, look at it, just look at it. If I tell you what I see, you’ll never see it for yourself!”

The man looked at the block of wood and said, “I see the tree rings.”

“Yes, go on, what do you see?”

“I see the tree rings getting wider and wider.”

“Yes, look at the middle of the tree, its first hundred years it grew three to four inches across, its second hundred years how far did it grow?”

“Three feet?”

“Now look around, just look at it, do I see any evidence? Do I believe that the climate is changing? It’s always about belief with your people, I don’t need to believe, I am here, I can see.”

I cracked another block in half, and another, seeing the growing season getting longer in each, a story written in circular lines, widening, growing quietly larger.

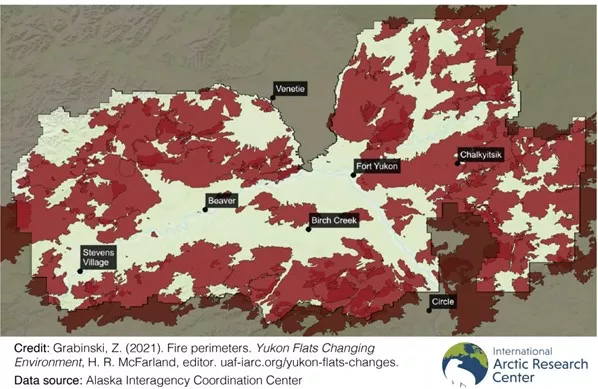

The lightning increased year after year, but unlike the trees, it leaves a different kind of growth behind, wildland fire. Gwich’in homelands have warmed more rapidly than any place in the Arctic, but just a few degrees more than other places in the North. The Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, an area about the size of Maryland, started to burn (Figure 3). Four Delawares’ worth of land has burned, over the last 60 years, immolated by an angry sky. Leaving rings of destruction. My life is from the boreal forest, the largest forest on planet Earth. The boreal forest is the largest terrestrial source of carbon on the planet. The forest itself holds as much carbon as the atmosphere for the rest of the planet combined. Compounding the issue is the fact that the forest insulates the permafrost of the North, which contains more than twice as much carbon as the atmosphere of the entire planet. These forests are subject to rapid change, as Gwich’in can attest. Our homeland was split apart by fire, smoke, lightning from the sky. What if the world’s boreal forest were to burn? What if the permafrost just below were to melt? We’ve seen 64% of the boreal in the vast Yukon Flats burn in a period almost equal to my short life. The world cannot afford to not consider the Boreal, to not look, to not see, to not be here, and understand that the fate of the boreal and its permafrost, is the fate of the world and all of its relationships.

Words echo in my ears like the thunder of that first storm as I walk in the boreal forests now. An ‘engine needs fuel,’ as I run my hands in the dry moss and sticks on the forest floor and look at the trees dry and ready to burn. ‘An engine needs air’ as the wind billows about, more and more frequently in the North. “An engine won’t run without a spark.” In the past, in the Arctic, and in the subarctic, the landscape composed a natural engine. An engine that ran for millennia, it served to capture carbon from the air like a net, and to tuck it down into the soil where it would become frozen. The forest would rise a little higher, year after year on the newly frozen soil, rich with carbon. It would go up and up, creating a paradise for all the Gwich’in and other peoples of the circumpolar North to live upon, the Saami, the Inuit, the Dehcho and Dene, the Ket. The boreal forest is the largest engine upon Earth, the greatest piece of terrestrial, natural infrastructure the world has known, an engine that took air, fuel, and the cold as a spark to sequester vast, world-changing, world-preserving, stores of carbon. More than three times more carbon and world changing methane than the atmosphere, and virtually no one can see it, nor, importantly to some, believe it.

The force of climate change has started to make this engine run in reverse. Gwich’in have had a front row seat to a world afire. Seeing the relationships between every creature, species of plant, and the climate itself change rapidly is the story we collectively know. Climate change doesn’t need our belief to be quite real. The smoke that choked the east coast of the U.S. and Canada recently wasn’t a fantasy, nor is it the end of the story, it’s the beginning. The boreal forest and all that it does, the natural infrastructure that allows life on Earth to exist, doesn’t need our beliefs, nor our political systems, or our systems of “governance.”

Gwich’in have long been subject to, and participants in, true ‘Arctic governance’: understanding the relationships of the natural world and our place in it. When is the Arctic not the Arctic? When we put people above all of the other relationships in the Arctic, when our thinking isn’t right or good, when we aren’t interested in taking only what we need and leaving no trace, we become blinded to the world and the meaning of our lives. This is why the Gwich’in, through Gwich’in Council International, are leading two wildland fire projects in the Arctic Council – the Arctic Wildland Fire Ecology Mapping and Monitoring Project and the Circumpolar Wildland Fire Prevention, Preparedness and Response Project. These projects try to get the world to see that our relationships to each other are only meaningful when we do meaningful things with each other, when we see each other, when we work towards common cause to jointly solve problems that we can’t solve alone. That we cannot allow the engine of our cooperation to atrophy and rust, all while our greatest challenge lies before us.

Arctic Exceptionalism Revisited: Fuel, Air, Spark

As we acknowledged at the opening of this article, there are many Arctics. Arctic scholars who make this claim are usually referring to the different characteristics and conditions of the Russian, Nordic and North American Arctics (physical, political, economic, social, etc.). This article introduces three stories that also validate the co-existence of multiple Arctics and expand our understanding of Arctic exceptionalism. We have discussed: 1) the Arctic as a space that, until very recently, was governed by the eight Arctic states, who have served as decisionmakers and gatekeepers of a protected zone of peace and cooperation; 2) the Arctic as a space with unique physical and environmental characteristics that is important to understand, manage and protect both for their intrinsic value and because of the region’s important position within global systems that are rapidly and dramatically impacted by climate change; and 3) the Arctic as a homeland for the Gwich’in and other Arctic Indigenous Peoples that hold Indigenous Knowledge and worldviews built on millennia of direct experiences and relationships on and with these lands. There may be discomfort in bringing these stories together, but each provides insights about what makes the Arctic exceptional and contributes to a broader understanding of the unique and innovative governance that has evolved in the region.

The Gwich’in story above discussed how an engine requires three things, existing in a specific relationship to one another to run: fuel, air, and a spark. We now extend this metaphor to consider how we can draw out elements of each of our three stories to provide a richer understanding of the engine of Arctic exceptionalism and the unique features of Arctic governance. We observe that each story contributes to the engine of Arctic exceptionalism. In the following sections we explore how the “fuel” can be seen as the incorporation of the different knowledges of these stories; the “air” as the governance environment and approach; and the “spark” as the opportunities and challenges facing the Arctic. This is not to suggest that these stories exist in harmony. There are inherent tensions between them, but they have all contributed to the region’s exceptionalism and governance in important and distinct ways.

Fuel: Knowledges

The engine of Arctic governance that produces cooperation and collaboration at the circumpolar scale runs on unique knowledges that have been the “fuel” of Arctic exceptionalism. Arctic states bring knowledge of the current geopolitical picture of the Arctic: global, regional, and domestic politics, policymaking processes, and authority structures. States also proved a conduit for scientific and Indigenous knowledges to directly and indirectly shape government policies, processes, and structures. But the flow of influence is not unidirectional. If Arctic governance at the geopolitical level is deemed to be exceptional for its focus on the collaborative pursuit of scientific knowledge, it has been influenced to be so by a growing global understanding of the unique features of Arctic ecosystems, their rapid transformations, and their critical role in global environmental systems. This Arctic exceptionalism exists at the intersection of the stories of Arctic geopolitics and environment.

Yet, the historic perspectives and knowledge of the Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic dwarfs the knowledges of modern geopolitics and science. The Gwich’in have knowledge that comes from a relationship with the land that has existed for millennia. On this timescale, the Arctic is constantly changing and humanity’s connection to the land creates a sense of unique responsibility and accountability. Indigenous Knowledge creates a fundamentally different worldview that places everything in relationship. With the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge by Arctic Indigenous Peoples in the work of the Arctic Council, and other circumpolar institutions, a distinct characteristic of how the Arctic is conceived is the inseparable relationship between nature, wildlife, and people that redefines our understanding of ecosystems and policy solutions. Over the last few decades, there has been a growing understanding and appreciation of Indigenous Knowledge in the Arctic by researchers and policymakers. The Arctic Council - thanks to the hard work and advocacy over many years by Indigenous leaders - has acknowledged the unique and important role of the region’s Indigenous Peoples. This was made possible with the creation of unique category for Indigenous Peoples organization (Permanent Participant) and, subsequently, the time and energy invested by these organizations in the Council’s discussions and decisions. While there is still a long way to go to address the power imbalances that exist, this inclusion of Indigenous perspectives is a hallmark of what makes Arctic governance exceptional: a step toward inclusive, consensus-based cooperation and away from factional, power-based competition. Toward emotional regulation, grounded and steady conversations, at the international level, and away from the erratic and unpredictable nature of cold and hot conflicts. The inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic Council has been recognized globally by policymakers and experts as an important innovation and a hallmark of Arctic exceptionalism.

Air: Governance Environment and Approach

To run the engine of Arctic exceptionalism requires “air”: a governance environment and approach that creates an atmosphere within which these knowledges can co-exist, interact, and shape institutional values and culture. In the context of the Arctic Council, this atmosphere was able to form, in part, by the exclusion of military security issues from the Council’s mandate, and by the low political salience of the region at the time that the Council was established. The peripherality of the Arctic allowed government officials, Indigenous leaders, and experts to talk, build relationships, share knowledges, commit to and engage in consensus-based decision-making processes, and establish meaningful cooperation to understand and solve Arctic problems. The Arctic Council became a vehicle for peace, science cooperation, and empowering Northern and Indigenous Peoples. Through relationships, these stories were intertwined, and a sense of common identity and purpose was able to form and shape the Council’s governance culture and approach. If Arctic governance is exceptional for its inclusion of Indigenous Peoples, it has been influenced to be so by Indigenous Peoples’ expressions of their values. This exceptionalism exists at the intersection of the geopolitical and Indigenous stories and moves Arctic Peoples and environments closer to center stage. It fosters deeper knowledge of history - all of it: western/southern and Indigenous/northern. This can be built upon. However, to the extent that an understanding exists which acknowledges a deeper Arctic history embedded within Indigenous Knowledge, there remains a “belief” to be tested and debated by distant agents of power who have only heard about it - not seen it - much like the understanding of climate change evinced by the visitor in the Gwich’in story. This aspect of Arctic exceptionalism, based on values of inclusion and consensus, is in danger.

Through the involvement of Indigenous Peoples and scientific experts, Arctic governance itself has gotten closer to the Arctic. Indigenous Peoples’ organizations help to ground often abstract discussions and bring the Arctic to high level meetings. They understand the importance of relationality in Arctic governance – people-to-people, land-to-people, inside-to-outside. Similarly, scientific cooperation means being there and helping the world to see (rather than believe) the transformations that are taking place. While Arctic states must continue to navigate where and how the Arctic fits geopolitically in the world and scientific experts seek to understand the relationships that connect ecosystems within and beyond the Arctic, Arctic Indigenous Peoples define the Arctic as home.

The Arctic Council, and the institutions that have adopted similar governance approaches in the region, have become a place for blending different stories and knowledges, and provide a more holistic view of Arctic issues and the solutions that will fuel its future. This is not to say that it is easy. Similar to bringing together the stories in this article, the experience can be clunky and uncomfortable. There are risks. Tensions between these stories continue to exist. Power imbalances remain. The unilateral decision of Arctic states to pause the work of the Arctic Council following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine without consulting the Indigenous Peoples organizations is an important and timely case in point of how all the air can be sucked out of the combustion chamber. However, the Arctic Indigenous Peoples organizations were open in their criticism of their exclusion (Arctic Athabaskan Council, 2022; Gwich’in Council International, 2022; Inuit Circumpolar Council, 2022) and, with the transfer of the Arctic Council Chair to Norway, we have seen concrete efforts to re-engage with Permanent Participants, experts, and Observers.

Spark: Opportunities and Challenges Facing the Arctic

Finally, the engine of Arctic exceptionalism needs a “spark." In this context, it is the opportunities and challenges facing the Arctic that have ignited the collective desires of leaders, officials, and experts to take action. The dramatic changes in Arctic ecosystems are essential to the story of geopolitics and inextricably linked to the rising participation of Indigenous Peoples in the region’s governance. The urgency to act on the discovery of high levels of pollution in what was perceived to be pristine Arctic environments was such a spark to initiate the Arctic Council. That spark still exists.

Over time, the importance and urgency of Arctic research has been increasingly realized and has been brought into international science-to-policy processes (e.g., IPCC, Minamata Convention, etc.). As a result, more and more people can see and know about the dramatic changes in the Arctic and its complex role in global systems. Initial and continuing interest in new shipping lanes is one thing; understanding that the Arctic is the world’s air conditioner, or that populations of bird species in far off countries, such as Australia, South Africa, and Chile, depend on breeding grounds in the Arctic, is another. Exclusion of non-Arctic states from Arctic governance structures becomes less and less tenable as, through science, we reach new levels of understanding about these relationships.

While no one should be excluded from this call to action, there is no question that the people that live in the Arctic have the deepest understanding of the unique opportunities and challenges facing the region, are the most impacted by the transformations currently taking place and are best positioned to identify the issues that require attention. Responding to challenges such as wildland fires, permafrost thaw, the decline of animal populations, and infrastructure deficits requires an ‘exceptional’ level of collaboration if the Arctic ecosystems and homelands are to be sustained.

Conclusions

Together, the stories of geopolitics, environment, and Gwich’in homelands in the Arctic provide a much richer sense of the engine of Arctic exceptionalism and the region’s governance. The engine of Arctic exceptionalism has run on a unique mix of knowledges (fuel), been nourished by a distinct governance environment and approach (air), and is catalyzed by real and pressing opportunities and challenges facing the Arctic (spark). The Arctic has been an exceptional space where hard security - competition and conflict - were set aside to make space for learning and for deeper understanding of underlying relationships. Its remoteness and the difficulty southerners faced in using the land, the fragility and charisma of the environment, the wisdom, strength, and grit of the Arctic Indigenous Peoples are all critical components of the engine that we call Arctic exceptionalism, manifested in the structures of governance people see and recognize as “Arctic.”

The Gwich’in have gathered to meet in council at Tł’oo Kat for a documented 15,000 or more years. So, it could be said that there have been many Arctic Councils, Arctic Councils all along throughout human history, rather than only the one that emerged in recent times. In this context, it is disheartening to see the Russian invasion of Ukraine so quickly unravel the relationships that have made the contemporary Arctic and its governance exceptional. The way we think when it comes to meeting challenges is what brings together knowledge and relationships to create action in the world. This can mean focusing on innovating for better governance, or it can mean abandoning our innovations in favor of more familiar responses to danger. In more recent months, there are some glimmers of hope that the breakdown of geopolitical exceptionalism in the Arctic does not need to result in the complete collapse of Arctic exceptionalism.

Despite its limitations and deficiencies, the Arctic Council has experience, and still holds potential, as a space where government officials, Indigenous leaders, and scientific experts can have substantive discussions, work to translate knowledges, and take on policy actions. Here we observe that exceptionalism is as much a process as it is an outcome. Taking the time to reflect on the many stories that make the Arctic exceptional is an important step in preserving and even fostering its unique and inspiring features within the region and beyond.

Spence, Jennifer, Edward Alexander, Rolf Rødven and Sara Harriger. “What Makes the Arctic and Its Governance Exceptional? Stories of Geopolitics, Environments and Homelands.” Arctic Yearbook, December 4, 2023

The full text of this publication is available via Arctic Yearbook.

- Arctic Athabaskan Council. (2022, February 14). Press Release: Conflict Continues in the Crimean Peninsula, Ukraine. ArcticAthabaskanCouncil.Com. https://arcticathabaskancouncil.com/conflict-in-the-crimean-peninsula/

- Arctic Council. (2016). The Arctic Council: A forum for peace and cooperation. Arctic Council. http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/our-work2/20th-anniversary/416-20th-anniversary-statement-2

- Axworthy, T. S., & Dean, R. (2013). Changing the Arctic Paradigm from Cold War to cooperation: How Canada’s Indigenous leaders shaped the Arctic Council. The Yearbook of Polar Law V, 7–43.

- Boudreau Morris, K. (2017). Decolonizing solidarity: cultivating relationships of discomfort. Settler Colonial Studies, 7(4), 456–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2016.1241210

- Byers, M. (2009). Who owns the Arctic. Douglas and McIntyre.

- Dodds, K. (2010). Flag planting and finger pointing: The Law of the Sea, the Arctic and the political geographies of the outer continental shelf. Political Geography, 29(2), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.02.004

- Dodds, K. (2019). Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198830764.001.0001

- Dodds, K., & Smith, J. R. (2022). Against decline? The geographies and temporalities of the Arctic cryosphere. Geographical Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12481

- English, J. (2013). Ice and Water: Politics, peoples, and the Arctic Council. Penguin Canada Books Inc.

- Exner-Pirot, H. (2023, May 11). Arctic Exceptionalism is Over. Who Will Tell the Diplomats? Eye on the Arctic. https://www.rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2023/05/11/arctic-exceptionalism-is-over-who-will-tell-the-diplomats/

- Gorbachev, M. (1987). Speech in Murmansk at the ceremonial meeting on the occasion of the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star Medel of the city of Murmansk, October 1, 1987. Barentsinfo.org. https://www.barentsinfo.fi/docs/Gorbachev_speech.pdf

- Gwich’in Council International. (2022, March 3). Re: Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine. GwichinCouncil.com. https://gwichincouncil.com/sites/default/files/2022%20March%203%20GCI%20Statement.pdf

- Heininen, L. (2005). Impacts of globalization, and the circumpolar north in world politics. Polar Geography, 29(2), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/789610127

- Heininen, L. (2018). Arctic geopolitics from classical to critical approach – Importance of immaterial factors. Geography, Environment, Sustainability, 11(1), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.24057/2071-9388-2018-11-1-171-186

- Ilulissat Declaration. (2008). Ilulissat Declaration. http://www.arcticgovernance.org/the-ilulissat-declaration.4872424.html

- Inuit Circumpolar Council. (2022, March 7). Statement from the Inuit Circumpolar Council Concerning the Arctic Council. InuitCircumpolar.com. https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/news/statement-from-the-inuit-circumpolar-council-concerning-the-arctic-council/#:~:text=We%20are%20concerned%20about%20the,a%201987%20speech%20in%20Murmansk.

- Koivurova, T. (2010). Limits and possibilities of the Arctic Council in a rapidly changing scene of Arctic governance. Polar Record, 46(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247409008365

- Łuszczuk, M. (2017). Changing foreign policy roles in the changing Arctic. In E. Conde & S. I. Sánchez (Eds.), Global Challenges in the Arctic Region (pp. 412–429). Routledge.

- Melchiorre, T. (2022, June 29). The Illusion of the Arctic “Exceptionalism.” High North News. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/illusion-arctic-exceptionalism

- Natanel, K. (2022). Affect, excess & settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel. Settler Colonial Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2022.2112427

- Nord, D. C. (2016). Creating an Arctic regime. In The Arctic Council: governance within the Far North (pp. 9–33). Routledge.

- Platjouw, F. M., Steindal, E. H., & Borch, T. (2018). From Arctic Science to International Law: The Road towards the Minamata Convention and the Role of the Arctic Council. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 9(0), 226. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v9.1234

- Rogne, O. (2015). Development of IASC. In IASC after 25 years: Special issue of the IASC bulletin (pp. 9–20). International Arctic Science Committee. http://iasc25.iasc.info

- Savage, L. (2023, February 17). The Arctic ‘will not be business as usual.’ Politico. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/global-insider/2023/02/17/the-arctic-will-not-be-business-as-usual-00083367

- Smith, J. (2022, August 19). Melting the myth of Arctic Exceptionalism. Modern War Institute At West Point. https://mwi.usma.edu/melting-the-myth-of-arctic-exceptionalism/

- Smith, L. C., & Stephenson, S. R. (2013). New Trans-Arctic shipping routes navigable by midcentury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(13). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1214212110

- Spence, J. (2017). Is a Melting Arctic Making the Arctic Council Too Cool? Exploring the Limits to the Effectiveness of a Boundary Organization. Review of Policy Research, 34(6), 790–811. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12257

- Steindal, E. H., Karlsson, M., Hermansen, E. A. T., Borch, T., & Platjouw, F. M. (2021). From arctic science to global policy – Addressing multiple stressors under the Stockholm convention. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 12, 80–107. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v12.2681

- U.S. Department of State. (2022, March 3). Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation Following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.

- Watt-Cloutier, S. (2015). The right to be cold. Penguin Canada Books Inc.

- Young, O. R. (2013). Governing the Arctic: From cold war theater to mosaic of cooperation. Global Governance, 11(1), 9–15.