When the UN Agreement on Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction was adopted in 2023, it was hailed as a milestone for marine biodiversity conversation. But in order for the new law, also known as the “BBNJ agreement” or “High Seas Treaty,” to take effect, at least 60 countries must ratify it.

Halting the triple planetary crises of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss will require massive commitment by all nations. But will the world’s leaders step up and deliver for the oceans?

In January, the Belfer Center’s Arctic Initiative, World Wildlife Fund (WWF)’s Global Arctic Programme, and the Norwegian Center for Law of the Sea of the UiT the Arctic University of Norway co-hosted a panel discussion at the Arctic Frontiers 2025 conference in Tromsø, Norway. The session aimed to raise awareness among Arctic experts of the treaty’s importance to the Arctic Ocean, as well as how the Arctic states, the private sector, and civil society could support the treaty’s ratification and implementation.

Watch the Recording

Read on for key takeaways identified by the panelists, Vicki Lee Wallgren, Director of WWF’s Global Arctic Programme; James Jansen, Senior Arctic Lead and Deputy Head of the Polar Regions Department in the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office; Margaret Williams, Senior Fellow at the Belfer Center’s Arctic Initiative; Kai Simon Eikli Yuen, Chair of the Arctic Economic Council and Advisor at the Norwegian Shipowners' Association; and Vito de Lucia, Director of the Norwegian Centre for the Law of the Sea.

What does the High Seas Treaty do?

The Agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction, also known as “the BBNJ agreement” or the “High Seas Treaty,” is an agreement under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that aims to ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in international waters.

UNCLOS, sometimes called the "constitution of the ocean," establishes rules for the world's oceans, including the delimitation of 200-mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) for coastal nations. UNCLOS' broad rules are premised, for the most part, on a regime of freedom, and UNCLOS lacks specific provisions for many activities in international waters - or high seas. The high seas do not belong to any state's jurisdiction, an area that includes much of the Central Arctic Ocean.

The BBNJ agreement complements UNCLOS by providing a legal basis and process for establishing area-based management tools and marine protected areas in the high seas. It creates a comprehensive legal framework in four areas:

- Regulation of the harvesting of marine genetic resources and ensuring equitable sharing of economic benefits;

- Protection of ocean habitats through the use of “area-based management tools,” such as designated shipping routes, areas to be avoided by certain industries, and fully protected marine areas;

- Requirement of environmental impacts assessments (EIAs) for activities that may adversely affect marine habitats in the high seas; and

- Establishment of “capacity-building” mechanisms, whereby developed countries support developing countries’ participation in the treaty through measures such as direct financial assistance or technology transfers.

Why is the High Seas Treaty relevant for the Arctic?

Rich Arctic Marine Biodiversity: The Arctic contains some of the largest intact marine ecosystems in the world, hosting 2,000 species of algae, tens of thousands of microbes, and over 5,000 animal species. Arctic Ocean species represent vast repositories of genetic diversity and are important food resources for both Arctic Indigenous peoples and the rest of the world. Every year, the Arctic witnesses some of the greatest marine mammal migrations in the world, with animals moving across political boundaries.

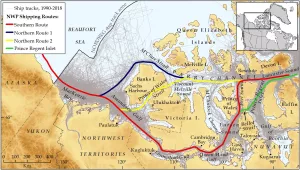

Increasing Maritime Activity and Related Risks: As year-round sea ice disappears in the Central Arctic Ocean, once-inaccessible areas in the high seas may attract extractive industries for the first time ever. Activities such as commercial fishing, trans-Arctic shipping, deep sea mining – perhaps even polar cruise tourism – could harm the marine environment and raise the risk of pollution. However, it is important to note that certain activities, such as trans-Arctic shipping, are not imminent threats to the Arctic Ocean. Panelist Kai Simon Eikli Yuen reminded the audience that delivering cargo on a tight timetable is essential to the shipping sector and, even as the Arctic Ocean loses its multi-year sea ice, the unpredictable conditions that will persist make development of the route unlikely.

Closing Legal Gaps: Although some international laws, such as the Polar Code and the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, provide for some types of marine protection in the Arctic, large gaps in the legal framework still exist. The BBNJ agreement can help close those gaps. Additionally, the BBNJ agreement will be a valuable tool to spur nations to meet the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework, to protect 30 percent of lands and waters by 2030.

How will the Arctic Council be involved in the High Seas Treaty?

Source of Expertise: Although the Arctic Council does not have the legal authority to implement the provisions of the BBNJ agreement, it will be a critical source of information and expertise for the BBNJ scientific and technical body. The Arctic Council’s Working Groups have produced many valuable syntheses of science and traditional knowledge and can continue to inform efforts to protect marine ecosystems in the Arctic. For example, the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) Working Group published the first State of Arctic Marine Biodiversity Report in 2017, and its biodiversity monitoring program could provide data on the status of Arctic marine life. The Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) Working Group has compiled a review of spatial planning tools that could be used to protect Arctic marine ecosystems, thereby contributing to the global goal of protecting 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030.

Convening Power: The official bodies responsible for implementing the BBNJ agreement can take advantage of the existence of the Arctic Council as a regional forum that convenes experts from all Arctic countries, is in itself an asset that can be tapped by the official bodies responsible for implementing BBNJ.

What is the status of the High Seas Treaty?

Worldwide: As of February 2025, 108 nations have signed the agreement. Only 14 countries have ratified it, but more are preparing to do so. For example, James Jansen, the Polar Lead for the United Kingdom, reported during the panel that the newly elected UK government has identified nature and climate as national priorities and considers ratification of the BBNJ agreement as part of that policy. Conservation groups are encouraging states to announce their ratification decisions at the United Nations Ocean Conference in June 2025.

In the Arctic: No Arctic nation has ratified the BBNJ agreement. Panel members agreed that this moment is an opportune one for Arctic states to work together to propel the BBNJ agreement by ratifying it. The United States is not likely to be among them, however, as the BBNJ agreement is an implementing agreement of UNCLOS. The United States is not a member of UNCLOS, though it recognizes many of its provisions as customary international law.

What challenges remain?

For the BBNJ agreement to make a difference for conservation in the Arctic and other oceans, a number of steps are still needed, some of which will be quite challenging. These include:

- Financing: Monitoring marine protected areas in the high seas is costly and difficult due to the vast distances involved. James Jansen also emphasized that developed nations had extra responsibility to support states in the Global South in meeting the treaty’s goals if it is to be a truly global agreement. Parties to the treaty must hash out a plan for providing adequate financial resources for implementation once the agreement enters into force.

- Balancing Scientific and Political Priorities: Although the focus of attention to the BBNJ agreement has been its future role in marine conservation, Vito de Lucia noted that the agreement is not only about protection but also makes provisions for exploitation, such as the harvesting of marine genetic resources (MGRs). One unique aspect of the agreement is that it will set forth rules on how the benefits from that industry will be equitably shared. Given that the treaty allows for harvesting of some resources within the high seas, conservation-minded voices will need to assert the primacy of marine protection over exploitation, a tricky balance to achieve.

- Working out the relationship of the BBNJ agreement to other international organizations with jurisdiction in the Arctic Ocean: A key clause in the High Seas Treaty states that the agreement must “not undermine” other bodies with jurisdiction in the Arctic Ocean. These include the International Maritime Organization (IMO), Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, the Oslo Paris Convention (OSPAR), the Northeast Atlantic Fisheries Commission, and the International Seabed Authority. It is not yet clear what upholding that clause will look like in practice. Continued dialogue is needed among existing legal instruments, as well as industry representatives and other interest groups.

How can the private sector and civil society support the High Seas Treaty?

Engaging the Oceans’ Greatest User: Panelists agreed that the shipping industry could play a major role in science and monitoring. Kai Simon Eikli Yuen emphasized that ship owners have a stake in ensuring safe, healthy seas, but perhaps more importantly, the industry also desires regulatory certainty and a predictable legal framework.

Civil Society Champions: Civil society was central to the successful negotiations of the High Seas Treaty. According to Vito de Lucia, organizations such as the High Seas Alliance and WWF, which provided professional input as well as unrelenting pressure, kept lawmakers focused on the task of finalizing the treaty. They also played an important role in capacity-building during the negotiations.

Williams, Margaret. “Thinking Beyond Boundaries: How the High Seas Treaty Can Serve the Arctic.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 21, 2025