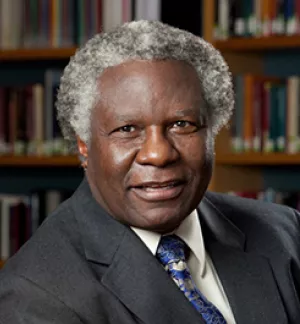

Obituary

When Calestous Juma was a boy, flooding created food shortages in his Kenyan village on the shores of Lake Victoria, so his father pioneered the planting of cassava, a starchy root that helped replenish supplies. His mother, meanwhile, was a farmer who switched to selling fish and other foods to help support the family.

“Being able to think about new things, doing new things, experimenting, was always a big part of my early childhood,” Dr. Juma said in an interview posted by the Cornell Alliance for Science.

Young Calestous was just as industrious as his parents. He was so adept at repairing household items such as radios and record players that at 12 his priest gave him dispensation to skip Mass so he could devote full attention to his work — which also helped pay for his education. “I had a job first, then retired into school,” he quipped to The Guardian, a London newspaper, in 2007.

Dr. Juma, who was director of the Belfer Center’s Science, Technology and Globalization Project at the Harvard Kennedy School, died in his Cambridge home last Friday of cancer. He was 64.

A professor of the practice of international development, and a writer of great range, he promoted technology for the poor and vulnerable throughout the world. He also wrote a book explaining why people are wary of innovation, and delighted his more than 100,000 Twitter followers by retweeting cartoons that ribbed those who are resistant to science.

Dr. Juma formerly served as executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and he founded the African Centre for Technology Studies in Nairobi, the first nonprofit on the continent that was dedicated to applying science and technology to sustainable development.

“To ministers and heads of state, he was a sought-after adviser, pointing the way toward reforms that boosted farm yields, educational standards, and economic prosperity,” Ash Carter, director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, said in a statement.

“To the scientific community, he was an unstinting champion of innovation and rigorous evidence,” added Carter, who is the Belfer professor of technology and global affairs. “To his students, he was a passionate teacher and mentor. To thousands of his fans on social media, he was a fount of insight, optimism and good humor. To us, he was a dear friend and extraordinary colleague.”

Uhuru Kenyatta, president of the Republic of Kenya, tweeted that “we have lost one of our most distinguished scholars and patriots.” He added that “those who had the pleasure of meeting him — or communicating with him online and off — will testify to his warmth, his love of learning, and his great generosity.”

In the 2016 book “Innovation and Its Enemies,” Dr. Juma drew from centuries of history to examine how societies sometimes try to reject evolving technology that subsequently becomes universal. “The dynamics of resistance to innovation have hardly changed over the 600 years that my book covers. This is partly because human nature has not changed over that period,” he said in an interview posted earlier this month on iafrikan.com, adding that “the key point here is that resistance to new technologies is driven by perceptions, not actual evidence.”

In the book, he wrote that “we celebrate the few technologies that have changed the world, but hardly remember those that have fallen by the wayside, not to mention the social tensions that surrounded their demise. . . . Between the successes and failures lies a large territory of contestation that deserves deeper exploration.”

At times he used Twitter to address, in a lighter fashion, the often raucous public debate over science. A few days before he died, Dr. Juma retweeted a cartoon of a fictional game show called “Facts Don’t Matter,” in which the host tells a contestant: “I’m sorry, Jeannie, your answer was correct, but Kevin shouted his incorrect answer over yours, so he gets the points.”

One of 14 children, several of whom died young, Dr. Juma grew up in Port Victoria, a small community in western Kenya on the shore of Lake Victoria, near the border with Uganda.

His father, John Kwada Juma, was a carpenter who also did fine cabinetry-making. His mother, the former Clementina Nabwire Okhubedo, was one of the first women to own land in the area, and transitioned from farming to entrepreneurial activities to pay for her children’s schooling, according to Alison Field-Juma, Dr. Juma’s wife.

Dr. Juma graduated from Egoji Teachers College and initially was a science teacher in Mombasa, on the eastern side of Kenya. While there, he gained renown for his lively and insightful letters to the editor of the Daily Nation newspaper, and made such an impression that he was hired as the publication’s first environmental journalist.

He subsequently was a researcher in Nairobi and was hired by political activist Wangari Maathai, who in 2004 became the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. In the early 1980s, Dr. Juma moved to England and graduated from Sussex University — first with a master’s then with a doctorate in science and technology policy studies.

While there, he met Alison Field, who also was doing graduate work. They married in 1987.

They moved to Kenya, where she set up a desktop publishing company and he founded the African Centre for Technology Studies, or ACTS — Africa’s first nonprofit that promoted policy-oriented research for sustainable development. In the mid-1990s, he became the executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. Dr. Juma joined the Harvard Kennedy School in 2002.

Along with his other responsibilities at the Belfer Center, he directed the Agricultural Innovation in Africa project, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In addition, Dr. Juma was on the selection jury for the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering, and he cochaired the African Union’s High-Level Panel on Science, Technology, and Innovation.

His many honors included receiving the 2017 Breakthrough Paradigm Award from The Breakthrough Institute. Citing Dr. Juma’s book “The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa,” the organization said it was recognizing “his scholarship and thought leadership in biotechnology and innovation. Of all global impacts on the environment, none has a bigger footprint than food and agriculture, and few scholars are better prepared to discuss and advise our agricultural future.”

In addition to his wife, Alison, Dr. Juma leaves their son, Eric of Boston, and a sister, Roselyda Nanjala of Port Victoria, Kenya.

A requiem Mass will be said in Holy Family Basilica in Nairobi on Jan. 4. Dr. Juma will be buried at his home in Port Victoria, Kenya, on Jan. 6. A Harvard celebration of Dr. Juma’s life will be announced.

“He was just an incredibly positive person,” his wife said, and that was the case even when he was ill and being treated for cancer. Every time he stepped into a cab or an Uber, she said, “he’d start talking with the drivers and hearing about their lives, and he was genuinely interested.”

Throughout his life, whether writing or undergoing treatment, delivering a lecture at Harvard or conversing with a cabbie, “there was never anything that was too difficult,” she said. “It was always, ‘Let’s just tackle it.’ ”

The Belfer Center has created a tribute page for Calestous Juma that includes links to obituaries, related media coverage, Juma’s research, a photo gallery, and more. We also invite you to submit your memories of this remarkable and beloved man using the comments form at the very bottom of this page.

Marquard, Bryan. “Calestous Juma, 64, Champion of Sustainable International Development.” The Boston Globe, December 22, 2017

The full text of this publication is available via The Boston Globe.