The Crisis in the Democratic West

Wolfson College

Oxford University

October 31, 2019

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. It is a very great honor for me to be here with you at Wolfson College.

I am grateful to President Tim Hitchens for this invitation to join others from around the world who have delivered lectures here this year on the theme of diplomacy and the 21st century.

On such an important evening as Halloween, I am surprised that anyone is here at all given the almost mythical status this particular holiday has achieved certainly in my own country and, based on my observations today, here in Oxford as well.

Had I been invited to speak with you four years ago this evening, I would have given a very different speech than the one I am about to inflict on you.

On October 31, 2015, the West, despite its problems and shortcomings, was the most stable, successful, and self-confident part of the world.

The United Kingdom and the United States were, four years ago, the bedrock countries of the West and the defenders of its faith.

Our economies were relatively strong, our political systems relatively stable and our prospects for the future relatively promising, especially compared to that part of the world governed by authoritarian rulers.

Our two countries had been operating in tandem since the Second World War as twin architects of the most successful international system in modern history – the Liberal Order. With the Atlantic Charter in 1941 our great wartime leaders, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, laid the foundation stone of a new world.

Some historians describe the Atlantic Charter as the foundational document of the West. When I left government, some of my British friends, led by Lord Peter Ricketts, gave me a framed copy of it with Churchill’s revisions penciled in.

I have it on my office wall at Harvard. It is not just a memento of my own special relationship with close British colleagues such as Lord Peter, Lord Robertson, Sir John Sawers, Sir David Manning, Sir Nigel Sheinwald, and Sir Emyr Jones Parry.

It is also a reminder of what our generation fought for during the Cold War. We saw ourselves in a long line of British and American diplomats who were inheritors of the world FDR and Churchill made possible.

When victory in the Second World War came four years after the Atlantic Charter, our two countries led in constructing a web of intersecting international institutions and declarations—the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, NATO, the Treaty of Rome—that helped to contain communism for nearly five decades after the war and have launched since a long reign of prosperity and great power peace. It was the Liberal Order that brought forth a world of laws, order, stability, human rights, democracy, and decency. It promised a better future to come.

That is the world bequeathed to us by Churchill and FDR, by Jean Monnet and Robert Shuman, by liberals and conservatives, by Christian Democrats and Social Democrats on the Continent, by Labour and the Tories here in the UK, by Republicans and Democrats in my country during the last seven decades.

It was a world order that we in the West believed was the only possible response to the utter barbarity of the Second World War and its 60 million dead globally.

It was a world order that helped us to survive the terrors and dangers of the Cold War. A world that saw the collapse of Communism beginning with the dramatic events at the Berlin Wall thirty years ago next week.

We should all wish to be transported back to that world that was still very much alive on October 31, 2015.

I say that, of course, because we find ourselves this evening in a very different world, one that is both more uncertain and more unstable and often deeply unsettling. One in which the UK and the U.S. are both suffering what can only be described as existential crises.

The United Kingdom is debating the simplest and yet the most difficult of questions. Who are we as a people? Are we Europeans? Or, are we, ultimately, an island race forever to play the role of permanent outsider to the main show on the Continent?

The United States, finds itself debating, usually sparked by a flurry of early morning tweets from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, how far from grace we have fallen.

In a country divided red-blue, north-south, urban-rural, liberal-conservative, we have returned to debating the foundational questions that we had assumed, for nearly eight decades, had been settled forever.

The debate is raging on my side of the Atlantic. Here are some of the questions in play:

Are we a country that prizes its traditional alliances, such as NATO and our East Asian Allies—Japan, South Korea, Australia—and sees them as the great power differentials between the U.S. on the one hand and Russia and China on the other? Or, will we be tempted, once again, to go it alone and live in the world without our allies?

Are we a country that seeks to uphold the global trade system that lifted a billion people out of poverty in the last four decades and brought unprecedented prosperity to our own country in the process? Or, will we now dismantle the entire edifice and turn back to building walls and moats around America?

Are we a nation that keeps its doors and windows open to immigrants and the 68 million refugees and internally displaced people in the world today—the greatest number since the summer of 1945? Or, will those doors now close to those with dark skin, those of the Moslem faith, those who come from our nearest neighbors in the Americas?

Are we a global power that will continue to support democracy when it is in peril as JFK and Ronald Reagan did with such conviction and relish?

I ask because our current leader embraces Kim and Xi and Putin and Erdogan and MBS while never failing an opportunity to castigate and dismiss Merkel and Trudeau, Macron and, for a time, Mrs. May?

We Americans were, not so long ago, among the proud guarantors of the liberal system. Democrats boasted we were the “Indispensable Nation.” Republicans were fond of proclaiming us as an “Exceptional Nation,” the centerpiece of global stability.

But now, in the Age of Trump, we are, in the eyes of many of our closest allies in NATO and around the world, and it pains me to say this, an “Agent of Instability” governed by an unpredictable, unreliable and, I fear, unredeemable President.

In the wake of your historic Brexit vote here in the United Kingdom and the election of Donald Trump in the United States, the world that we knew, the world that we built, feels as if it has been knocked clear off its axis.

We have lost something that is vital to a successful country—our balance, our perspective and perhaps even our self-confidence in who we are and in what we believe.

In contrast, the authoritarian powers are brimming with self-confidence about how they intend to lead—through “re-education” camps, Great Firewalls, the surveillance state, occupations and annexation of other peoples’ lands, ethnic cleansing, and murders of journalists.

And just to make things even more challenging, we are living through a moment of decisive change and turbulence beyond our own two countries.

A geopolitical moment that is perhaps the most troubled period since the height of the Cold War thirty-five years ago, if not well before.

The global stars are realigning in dramatic fashion.

China is returning to power in Asia and in the world. For eighteen of the last twenty centuries, China has had the world’s largest economy. After its subjugation by the West from the Opium Wars of the 1840s until the end of the Japanese Occupation during World War Two, China is returning to its natural place in the universe—of vast economic power—and with bold ambitions to dominate again in the Indo-Pacific.

The long reign of Europe in world affairs, on which the sun did not set during the last five centuries, is coming to an end. Europe, especially the European Union and NATO, are still powerful. The European Union economy is a global force. But, Europe would be hard-pressed to defend itself without the U.S. link through NATO. And Europe’s strategic orientation is toward regional but not truly global power.

The once mighty Russians are declining on a long, downward glide path—heading toward the Second Division of global power by mid-century. But, their wily, agile and opportunistic President, Vladimir Putin, the most experienced leader in the world today, still has Moscow punching well above its weight class as his Presidency for life heads into its third decade.

By mid-century, our children and grandchildren may rank India, Brazil, Nigeria, and Indonesia as rising great powers coming into their own at long last.

And the digital revolution underway—the awesome power of artificial intelligence, machine learning, quantum computing and biotechnology—may change our lives more during the next thirty years than the Information Age did during the last thirty.

These massive changes in the balance of power, in technology and in prevailing public attitudes, compel us to set a new course.

This is where diplomacy can help our two countries to recover and to move forward again.

But, diplomacy will not work and cannot succeed if it is not cemented in clear moral and strategic foundations.

Diplomacy can’t be effective if it does not spring from a set of ethical principles and strategic objectives that are harmonious with the values and traditions of the nation itself.

One of the reasons that American diplomacy under President Trump has not succeeded in any meaningful way on any major issue during the past two and one half years is the lack of such a solid foundation of principles from which to draw guidance as well as inspiration.

Under President Trump, we are a nation adrift, unmoored from the democratic principles and open attitudes about the world that helped after World War Two to make us a great power.

He operates not on a comprehensive global strategy but on a series of one-off transactions, each seemingly unrelated to the other.

Trump’s foreign policy has no discernible theme, no carefully crafted strategy, no unity, and no hopeful promise of a noble goal—stability, justice, or peace. Rather, it seems to boil down to a deal in this place or that where one country loses and another gains in a zero-sum world.

The irony in this current crisis is that America is still, by a substantial margin, the most significant economic, military, and political power in the world. We will likely be so a decade or two or even more, hence.

The rest of the world, however, is watching us quizzically and warily.

For the first time in over eighty years—since the 1930s—the rest of the world does not know quite what to make of the United States.

They worry we may succumb, once again, to the isolationist gene in our national DNA. George Washington warned us about entangling alliances. A successor President, John Quincy Adams, joined him in signaling danger in the world beyond our shores when he said memorably about America on July 4, 1821, “...she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

Two centuries later, in a very different world, our friends and allies cling to the hope that our quite noticeable drift from global leadership on climate change, refugees, immigration, NATO, and many other issues and institutions is just a momentary infatuation before we return to reason and a global vocation once again.

We will likely not have an answer to this fundamental question about America’s place in the world until our Presidential election just about a year from now in November 2020.

Wolfson College has sponsored lectures this past year on the art, practice, and promise of our craft—diplomacy.

Given the state of world disorder, the task of diplomacy in the United States, in the United Kingdom and around the world is to rebuild in the spirit of the 2020s, a renewed liberal world of hope, promise, tolerance, reason, and global cooperation for the future.

And the challenges ahead may be the most daunting any generation has faced in many decades.

First, can we in the 195 nation states in the world recognize that many of the most important dangers ahead in this next decade are transnational in nature? They envelop all of us. We cannot resolve a single one unless we work together as a global nation to conquer them.

These challenges include climate change, trafficking of women and children, crime and drug cartels, the threat of pandemics, and the multiple cyber threats that can destabilize our world.

The U.S. cannot succeed on any of them if we act alone in the world.

Second, how should we respond to the many China challenges?

The China that seeks to supplant us as the predominant power in the Indo-Pacific;

The China that seeks to exceed us in military power in the next decade by racing ahead to create new revolutionary military technologies through the weaponization of A.I. and quantum computing;

The China that won’t play by global trade rules and that continues to rip off the intellectual property of American, European, and Asian firms;

The China that believes its authoritarian system is the wave of the future rather than the democratic model that we Americans and Brits hold up as the international standard;

And, conversely, the China we cannot live without if we hope to mitigate environmental catastrophe and engineer a stable, global economy;

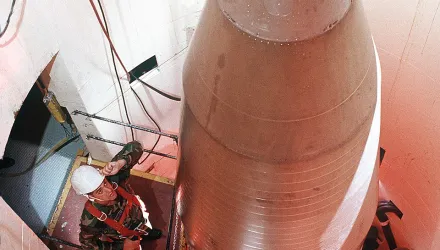

Third, we are witnessing the unraveling of the nuclear weapons treaties that brought stability and rules and limits to the arms race among the great powers over the last half century.

In just the last year, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty between Russia and the U.S. has been allowed to expire.

The New START agreement that has limited strategic intercontinental ballistic missiles between the United States and the Russian Federation may well expire in 2021 without a change of heart in both capitals.

There are now no limits whatsoever on China’s nuclear weapons programs or that of Pakistan or Israel.

After over fifty-five years of seeking to control the size and type and spread of these weapons, we are now living in a nuclear wild west.

Through reinvigorated diplomacy, we must rebuild the case for arms control and create the condition for a new generation of limits on the most destructive weapons that threaten the peace, including cyber weapons.

Those are just three critical challenges ahead. There are many, many more. It is thus understandable that we might—all of us— feel tonight rather skeptical that our government can give us hope of future success.

How can it be otherwise for Americans when we see the bipartisan dysfunction in Washington, and the cynicism in its halls of power? Do our political leaders have the fortitude and courage to cast aside tribal passions and partisan differences and do what is right—to make our democracy work again?

I interviewed former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice at a public forum in Aspen, Colorado two years ago. And I asked her this question: “What do you worry about?” I had in mind dangers on the global horizon—Putin’s aggression in Ukraine, Kim Jong-un’s growing nuclear arsenal, and Iran’s Middle East power play.

But she chose to interpret the question differently. Without missing a beat, she said in response to my question: “We’ve lost our self-confidence.”

“We’ve lost our self-confidence.”

She was not criticizing any U.S. leader in particular. I think she was commenting on the national mood.

I have thought a lot recently about this loss of faith in America’s global role.

We were once a great nation. We were FDR’s nation that beat the Great Depression and organized the defeat of Hitler and the Tojo in World War Two. We were Eisenhower’s nation that built the Interstate Highway System. We were JFK’s nation that sent men to the moon and returned them safely to the earth within one short decade.

We were Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s nation that convinced the majority of Americans finally to face the original sin of our founding and that restored to African-Americans the rights that should have been theirs all along.

And in our own time, it was our nation—our scientists and engineers, our geeks and Silicon Valley dreamers—that propelled the information age and now the digital world that is changing life on earth—in most ways for the better.

As we debate as a nation how we can meet the China challenge, defend our democracy, sustain economic growth, and confront the income inequality that lies at the root of much of our national discord, we would do well to remember that we are still the most powerful nation in the world and still the most capable nation to help lead the world in taking on the challenges of the future.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the problems of the U.S. are not dissimilar in their essentials from the problems of the United Kingdom. Despite them, however, there are still many reasons why we should both believe that our problems can be overcome and that we can feel confident about the future. While the Chinese may be gaining on us, and Putin won’t go away, they are not ten feet tall.

Britain and America, let us not forget, have many strengths.

Economists will remind us that our 21st century economies are built for success with our global lead in innovation, information, and digital technologies—the foundation stones of the future.

We have some of the finest universities in the world from Oxford and Cambridge, Imperial College and Edinburgh, the University of Chicago, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, MIT, Harvard, and many, many more.

Our banking, private equity and venture capital firms are still the most flexible and successful globally.

We have, as you all know, the strongest, most adaptive, and disciplined militaries in the world and first class diplomats in the FCO and State Department.

We have the irreplaceable NATO Alliance.

And unlike China, we are governed by the rule of law and free democratic elections.

We have many reasons to be hopeful tonight.

It may take both of us some years to recover fully from the ravages of your Brexit debate and the ravages of Trump.

We will both need to work hard and creatively to dig out of the one hundred meter holes we have dug for ourselves.

But we should have faith in the strength of our societies, in our peoples, and in the deep democratic traditions in the UK and the U.S.

There is in both of our national characters an abiding dedication to build what Tennyson called a “newer world.”

Winston Churchill may have had exactly this theme in mind when he visited Harvard University in the middle of the Second World War on September 6, 1943.

It was a pivotal moment in the war. By then, the Soviets had defeated the German Sixth Army of von Paulus at Stalingrad. The British Eighth Army under Montgomery had defeated Rommel’s Afrika Corps in the Egyptian desert at El Alamein. The Americans had conquered Sicily and were about to embark on the Italian Campaign. In short, the allies had turned the tide and were very likely going to emerge victorious—to win the war.

There was something else happening as Churchill stepped into Harvard Yard that day. The long run of the British Empire as the world’s greatest power was coming to an end. The United States, its cousin, had, by September 1943, overtaken Britain as the world’s undisputed political, military, and economic power.

So, picture Churchill standing on the steps of Harvard’s Memorial Church with six thousand young American students at attention before him in their cadet uniforms, leaving school to be trained and then to be catapulted into the two-front war in Europe and the Pacific.

It was as if Churchill was handing the baton of leadership—of global leadership—to those young Americans seventy-six years ago this autumn.

And in a very long and very good speech, here was the key bit of advice he had come to Harvard to offer those young Americans:

“The price of greatness,” Churchill said, “is responsibility.”

“The price of greatness is responsibility.”

His message—if you want to be great, you must take responsibility for your role in the world.

Churchill went on to say in words that are as fitting and relevant today as they were in the middle of World War Two:

“….one cannot rise to be in many ways the leading community in the civilized world without being involved in its problems, without being convulsed by its agonies and inspired by its causes.”

Great nations do not abandon their responsibilities. They do not pull back from global leadership, pull up the drawbridges, and cower from what is happening in the rest of the world.

The America and the United Kingdom that made our modern world more prosperous, more stable, more just, and more peaceful have not disappeared.

Please be patient with us Americans as we endure our existential crisis. And we pledge to be patient with you, as well.

With the right leadership, we can be those great nations again.

Thank you.

Burns, Nicholas. “The Crisis in the Democratic West.” October 31, 2019