How to Build a New Digital Order

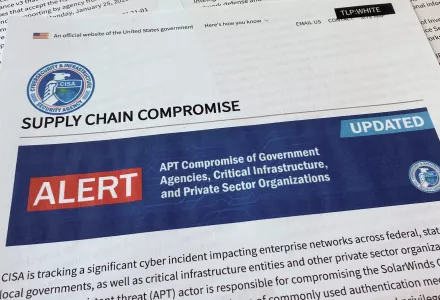

Ransomware attacks, election interference, corporate espionage, threats to the electric grid: based on the drumbeat of current headlines, there seems to be little hope of bringing a measure of order to the anarchy of cyberspace. The relentless bad news stories paint a picture of an ungoverned online world that is growing more dangerous by the day—with grim implications not just for cyberspace itself but also for economies, geopolitics, democratic societies, and basic questions of war and peace.

Given this distressing reality, any suggestion that it is possible to craft rules of the road in cyberspace tends to be met with skepticism: core attributes of cyberspace, the thinking goes, make it all but impossible to enforce any norms or even to know whether they are being violated in the ,rst place. States that declare their support for cybernorms simultaneously conduct large-scale cyber-operations against their adversaries. In December 2015, for example, the UN General Assembly for he ,rst time endorsed a set of 11 voluntary, nonbinding international cybernorms. Russia had helped craft these norms and later signed o. on their publication. That same month, it conducted a cyberattack against Ukraine’s power grid, leaving roughly 225,000 people without electricity for several hours, and was also ramping up its e.orts to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. For skeptics, this served as yet further evidence that establishing norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace is a pipe dream.

Yet that skepticism reveals a misunderstanding about how norms work and are strengthened over time. Violations, if not addressed, can weaken norms, but they do not render them irrelevant. Norms create expectations about behavior that make it possible to hold other states accountable. Norms also help legitimize official actions and help states recruit allies when they decide to respond to a violation. And norms don't appear suddenly or start working overnight. History shows that societies take time to learn how to respond to major disruptive technological changes and to put in place rules that make the world safer from new dangers. It took two decades after the United States dropped nuclear bombs on Japan for countries to reach agreement on the Limited Test Ban Treaty and the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

Although cybertechnology presents unique challenges, international norms to govern its use appear to be developing in the usual way: slowly but steadily, over the course of decades. As they take hold, such norms will be increasingly critical to reducing the risk that cybertechnology advances could pose to the international order, especially if Washington and its allies and partners reinforce those norms with other methods of deterrence. Although some analysts argue that deterrence does not work in cyberspace, that conclusion is simplistic: it works in different ways than in the nuclear domain. And alternative strategies have proved equally or more deficient. As targets continue to proliferate, the United States must pursue a strategy that combines deterrence and diplomacy to strengthen the guardrails in this new and dangerous world. The record of establishing norms in other areas offers a useful place to start—and should dispel the notion that this issue and this time are different....

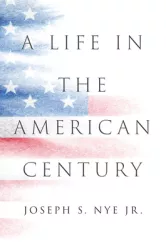

Nye, Joseph S. Jr. "The End of Cyber-Anarchy?" Foreign Affairs, vol. 101. no. 1. (January/February 2022) : 32–42.

The full text of this publication is available via Foreign Affairs.