Last month, the Arctic Initiative held a closed-door seminar for climate scientists, regional experts, Indigenous and youth leaders, and national security officials from six Arctic states. Our goal was to identify the most plausible scenarios (end-states) and pathways (path-dependent processes leading to end-states) for how geopolitics linked to climate change in the Arctic might evolve and identify actionable steps that the U.S. government might consider taking today to manage emerging risks. The event was conducted off the record, with a lively and wide-ranging discussion.

This report summarizes my key takeaways from the event for a public audience. I should emphasize that the group brought to bear a wide range of perspectives and did not seek to establish unanimous agreement on any specific items. The views below are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views or conclusions of any of the participants.

The Outlook from 2023

Climate change is already transforming the Arctic. Temperatures in the region are rising 3-4 times faster than the global average. Sea ice is trending down by every relevant metric, especially between April and September, opening new navigation routes and expanding access to marine resources. Permafrost thaw is impacting infrastructure across the region, increasing the risk of environmental accidents. Extreme weather events are on the rise. Sea level rise is accelerating, though its impacts will be global and longer-term in nature.

Under all plausible scenarios, global warming will continue, and the Arctic will keep warming faster than the global average. By mid-century, the frequency and severity of heatwaves, extreme precipitation and flooding, wildfires, disruption of marine food webs and fisheries, sea level rise and coastal inundation, droughts, and potentially climate-refugee flows are all likely to increase. The impacts on Arctic communities will be especially severe. Some will have to relocate. Others will have to adapt, at great cost and inconvenience. The rate of change for many impacts is forecast to increase in roughly linear fashion through mid-century—and to accelerate thereafter in the higher-emissions scenarios. In short, it is impossible to plan for the Arctic in 2050 without anticipating a future of dramatic climatic and geographic transformation.

However, our ability to forecast the future of climate change is also limited by several kinds of uncertainty. Uncertainty about the future pathway of global emissions means that there is no single baseline forecast for the extent of climate change by 2050 or any other year. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s scenarios range from extremely optimistic to extremely pessimistic. Within each emissions scenario, models yield different median estimates and levels of uncertainty. The IPCC’s middle emissions scenarios currently appear most likely, though it is impossible to have certainty. There is no single “tipping point” of warming for Arctic climate change. In short, the extent of long-term Arctic climate impacts depends largely on actions we take today, but climate change mitigation and adaptation are both essential and complementary strategies. The United States can and must invest in both. To build resilience, policymakers also need an organized framework for thinking about how climate change, and the steps they take in response to climate change, will interact with geopolitical and economic trends in the region.

Climate change is already affecting geopolitics, and countries are adapting their geopolitical strategies to take account of anticipated future climate change. Russia is leading in this regard, explicitly integrating climate change forecasts into its economic and national security strategies. Vladimir Putin has signaled that he sees the Arctic as an essential resource base and military stronghold for Russia in the decades ahead. Putin also seems to believe that unexploited hydrocarbon resources in the Arctic will be crucial for Russia’s economic future post-Ukraine. Scientists and industry participants are skeptical that this plan will succeed, but the exit of Western firms has removed pressure on Russian policymakers and firms to guard against Arctic environmental risks. Russian activity is increasing the probability of Arctic environmental disasters in the years ahead, including oil spills and radiological leakage.

The United States and its Arctic allies and partners cannot ignore Russia’s actions. As the war in Ukraine still rages, a future military confrontation between Russia and NATO in the Arctic cannot be ruled out. NATO faces the challenge of how to strengthen its defense structures and increase the frequency and scope of Arctic exercises without risking misperceptions and accidents that lead to conflict with Russia. Moscow’s diplomatic isolation and economic weakness may also force it to grant China a greater role in the development of the Northern Sea Route. A Chinese military presence in the Arctic is unlikely ever to serve Russian interests, but a prolonged Ukraine war, in which the Putin regime remains in power, likely points to deeper and broader Sino-Russian collaboration.

The Chinese Communist Party has its own view of the climate-geopolitics nexus. Chinese experts discuss direct impacts of climate change as a multi-dimensional national security threat. Across China, climate-induced natural disasters could potentially produce financial stress, migration, and even social unrest. Overseas, however, Chinese academic and policy literature hints that climate change is indirectly producing economic and geopolitical opportunities that China could exploit. The Arctic is seen as the region where climate-related opportunities are most obvious. China’s end-state vision for the Arctic is unclear—but commentary by Chinese politicians and scholars about the Arctic as a “new strategic frontier” imply that Beijing’s long-term aspiration is to play a role in rewriting and reshaping the Arctic’s existing governance rules and institutions.

Climate science is an essential early step in China's longer-term strategy to become a “polar great power” (极地强国). In the short term, China has attempted to play Russia and the United States against each other as it expands its Arctic presence, but it has met resistance. China sees scientific collaboration as a pathway to establish a physical presence in the region without arousing suspicion from Arctic states. China also cites climate change as the legitimizing reason for its Arctic aspirations. To achieve China’s long-term aspirations, it needs a “strategic pivot point” (战略支点)—a port in the in the region that it substantially controls, in a country that would not abandon China in a crisis. Greenland, for several reasons, is the ideal candidate. The fact that prominent Chinese commentators have explicitly articulated this strategy poses a dilemma for the United States. China has a legitimate right to pursue peaceful scientific research in the Arctic, and scientific cooperation on climate-related issues benefits the entire international community. However, it would not serve U.S. interests if China manifested the rest of its strategy, using Russia or other regional proxies to insert itself into regional governance and asserting its own interests over those of circumpolar states and communities.

Scenarios and Pathways

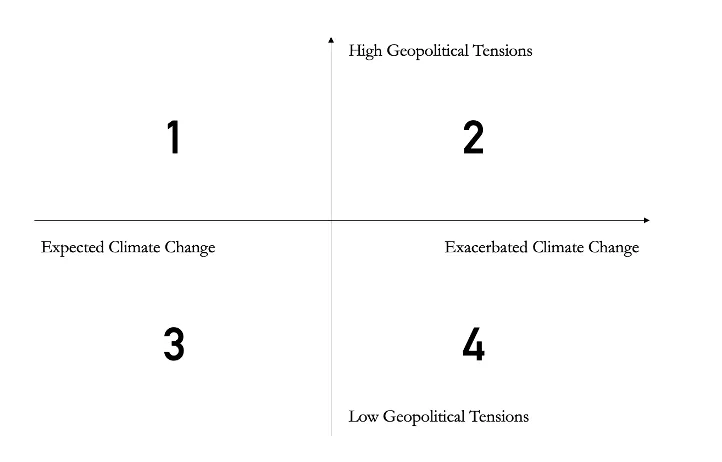

Based on the workshop discussions, I drew up four scenarios that reflect relatively optimistic and pessimistic outcomes for direct climate impacts and geopolitics. The scenarios are summarized in a 2x2 matrix below.

All four scenarios assume that global emissions follow one of the IPCC’s middle emissions pathways (RCP 4.5 and 6), that global climate financing remains inadequate, and that geopolitical competition among the United States, China, and Russia rises. Détente between any two probably means more intense competition with the third. None of these assumptions are certain, of course, and tail risks cannot be excluded. However, the 2x2 matrix is a helpful first step in thinking about potential climate-geopolitics interactions.