Sanctions relief are at the core of the P5+1 (United States, United Kingdom, Russia, China, France, and Germany) and Iran nuclear negotiations, and although negotiators are somewhat tight-lipped about the details of lifting sanctions, expectations for Iran’s return to economic normalcy are running high. Although reports indicate that there has been some movement over the “snapback” provisions—that is, the protocols to reinstate multilateral sanctions should Iran fail to uphold its commitments—Iran’s aim to regain economic normalcy will take more than lifting US, EU, and UN sanctions. Many unilateral and non-nuclear sanctions will remain in place despite successful negotiations; and until Iran institutes major legal and structural reforms within its financial sector—to fall in line with international standards—banks and other global financial institutions will continue taking a cautious approach to reengagement. Consequently, non-nuclear sanctions and banks’ continuing fear of criminal and civil penalties could keep Iran largely frozen out of international financial markets even after a nuclear deal.

Iran has steadfastly maintained that without sanctions relief, there will be no deal. And for good cause— reaching a nuclear deal that provides complete sanctions relief will be a game-changer for Iran—a necessary step to begin recovering from years of economic mismanagement and to begin normalizing global ties. At the 2014 World Economic Forum in Davos, Iran’s President, Hassan Rouhani, gave a broad-stroke agenda for addressing Iran’s economic woes, which are largely a result of years of economic mismanagement, as well as sweeping unilateral and multilateral economic sanctions. Mr. Rouhani’s strategy includes reopening trade with its neighbors, furthering privatization, increasing lending to its private-sector, and ramping up revenues from non-oil exports.

In light of a possible deal, Iran has already started adjusting its monetary policy to absorb the effects of lifting sanctions. Curbing high inflation is a number one priority of the Central Bank of Iran, and in an important step, Iran’s Central Bank will unify the official and “black market” exchange rates once negotiators reach an agreement. This structural adjustment, although it will likely contribute to accelerated domestic inflation, will be good for Iran’s business environment—reducing corruption and rent-seeking that occurs with separate exchange rates. Externally, Iran has been laying the ground work for increasing its regional and global economic and political ties. Earlier this year, China accepted Iran as a founding member of the new, China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. As a competitor to Western-dominated lenders like the World Bank, membership in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank strengthens Iran’s economic and diplomatic footing with Asia. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which is a regional group with a long-term objective to improve economic stability and free-trade in Asia, has also promised to upgrade Iran’s status should negotiations prove successful.

Challenges remain. Nevertheless, deficiencies in Iran’s financial rules and regulations could make normalizing economic ties difficult. In a statement this past February, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)—an inter-governmental body responsible for setting standards and promoting policies to protect the integrity of the international financial system— reaffirmed its call on member states to, “…advise their financial institutions to give special attention to business relationships and transactions with Iran, including Iranian companies and financial institutions.” According to FATF, Iran has failed to make meaningful progress towards addressing its anti-money laundering and terrorism financing deficiencies. The lack of criminal laws addressing terrorist financing and requirements for its financial institutions to file suspicious transactions reports is particularly troubling considering Iran’s top regional and global trading partners all have similar laws and regulations.

Since 2009, as a result of the deficiencies in Iran’s financial sector, FATF has called on its 36 member states to apply “effective counter-measures” and maintain vigilance when conducting transactions with Iran. Although FATF leaves it up to its members states to determine what the “counter-measures” will entail, the US has designated Iran’s entire banking sector—including the Central Bank of Iran— as a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern,” using authorities under Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act. Regardless, then, of whether or not the P5+1 and Iran reach an agreement, this designation against Iran will stay in place, and other FATF members are obligated to maintain similar measures.

The other nuclear option. Dubbed by Washington insiders as Treasury’s “nuclear option,” a Section 311 designation effectively prevents targeted entities from using the US financial system and transacting in US dollars. More specifically, the finding prohibits US banks and financial institutes from opening or maintaining correspondent accounts with Iranian institutions, and also requires US banks to take special measures to ensure Iran does not indirectly use the US correspondent banking system. Only used eleven times, the Economist points out that, “a 311 designation is more often than not a death sentence.”

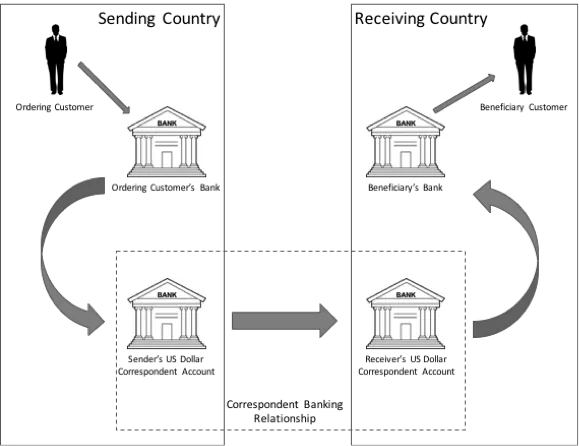

International trade and finance depends heavily on correspondent banking, and the US financial system plays a central role. Domestic banks, for example, may have limited access to foreign financial markets, but require a means to service their customers. This is where correspondent banking comes in. These accounts essentially act as the domestic bank’s agent abroad. For reference, Figure 1, illustrates the basic premise of a correspondent banking transaction.

But, the secondary effects of a 311 designation can be just as damaging—if not more so. The global financial system views 311 designations as ‘radioactive’—too risky to deal with. As a consequence of the Section 311 designation, as well as the increasingly severe sanctions, banks have taken a risk-adverse stance towards Iran (as well as other sanctioned countries)—even going so far as shutting down wholesale lines of business rather than manage associated risk—a process dubbed “de-risking.” In a2014 statement before the ABA Money Laundering Enforcement Conference, Treasury Under Secretary David Cohen noted that de-risking can, “…undermine financial inclusion, financial transparency and financial activity, with associated political, regulatory, economic and social consequences.” Without serious changes, the hyper-sensitivity to risk within the global banking system could no doubt hamper Iran’s return to economic normalcy.

The severity of a Section 311 designation becomes quite apparent when considering the dominance of the US dollar in global trade finance and banking. According to the International Monetary Fund, countries hold approximately sixty-three percent of foreign exchange reserves in US dollars. Euros are the next preferred reserve currency, at twenty-two percent. Global payments are largely conducted in US dollars as well. According to SWIFT, which is the leading global financial messaging service provider, the US dollar accounted for forty-five percent of all global customer initiated payment traffic. While US dollar-denominated payments could surely flow around the US financial system, this is costly and something banks would rather avoid. Thus, a ban from using US correspondent accounts—either directly or indirectly—can be a major impediment in conducting international trade and commerce.

To be sure, changes in the global currency markets are shifting. Russia and China, for example, are bringing new financial messaging systems online this year, which will provide alternatives to the SWIFT-dominated market. Also, China continues to globalize its currency, the renminbi, as a way to lessen the reliance on the US dollar. Regionally, the renminbi—as a currency for trade in Asia Pacific—increased 327 percent between April 2012 and April 2015, and puts China’s currency in the number one spot—accounting for thirty-one percent of all payments. Globally, the renminbi is the fifth most active currency, accounting for almost two percent of payments worldwide. For comparison, the renminbi accounted for only 0.31 percent of global payments in 2011. Yet, despite these changes, most analysts do not believe that the US dollar will lose its dominance within the next decade.

So what should Iran do? FATF outlines forty recommendations that countries should implement to protect the international financial system from money laundering, terrorist financing, proliferation financing, and other threats. To be sure, Iran undertook a process in 2008 to restructure its anti-money laundering laws and regulations, largely with technical assistance from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime and the International Monetary Fund—even going so far as to set-up a nascent financial intelligence unit. Yet key gaps remain. Compared to the UN’s model anti-money laundering legislation, Iran’s laws are relatively weak and lack key components, such as criminalizing terrorist financing, “know-your-customer” and beneficial owner regulations, and a comprehensive system for identifying, recording, and disseminating suspicious transaction reports. Also missing are robust processes and procedures for freezing and seizing assets.

In 2011, Iran’s central bank issued additional guidelines for identifying customer activities related to money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Still, these efforts do not appear to be enough, according to international bodies like FATF. According to a 2011 UN report on the implementation of UN security council resolution 1373—a resolution adopted in 2001 aimed at criminalizing the financing of terrorism—Iran still requires the operational measures to counter the financing of terrorism. Moreover, Iran is still not a signatory to the 1999 UN International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism.

Coming into line with international anti-money laundering standards and conventions will only help to facilitate the process of lifting the FATF “black-listing” and the US Section 311 designation. There is no doubt that lifting sanctions will help Iran regain normal economic status, both regionally and globally. But without significant reforms, banks’ increased sensitivity to risk and the inability to access the US financial system will leave Iran in a perpetual state of isolation from global finance—stunting its prospects for creating a climate conducive to economic investment. The question that remains, then, is whether or not Mr. Rouhani carries enough political capital to challenge those who may be benefiting from weak anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing laws and regulations.

Arnold, Aaron. “Iran's Radioactive Financial Industry.” June 12, 2015