Featured in the Fall 2021 Newsletter »

Considering Women in Afghanistan and Other Combat Areas

Zoe Marks is a Lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School. Her research and teaching interests focus on the intersections of conflict and political violence; race, gender and inequality; peacebuilding; and African politics. Professor Marks also examines how wartime experiences shape individual wellbeing and community reintegration after war. Charli Carpenter is an International Security Program Fellow and Professor in the Political Science Department at University of Massachusetts-Amherst. Her teaching and research interests include international law and human security, protection of civilians, humanitarian disarmament, and advocacy networks.

We asked Marks and Carpenter to share their thoughts on how the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the war in general, has impacted Afghan women, and what the women themselves and others can do to improve their situation.

When the Taliban took control in Afghanistan following the withdrawal of American troops, one area of global concern was how Taliban rule would effect Afghan women. What impacts have you seen on women since the withdrawal and what do you expect in the coming year?

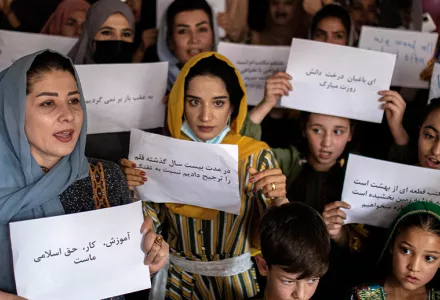

Marks: The first thing we saw was women-led protests in the streets of Kabul and other cities, where women mobilized against the Taliban despite the risks involved. Since September, though, the Taliban’s violent crackdowns and restrictions on protest and free speech have made it nearly impossible for women to protest and we've seen staggering levels of gendered repression. Women are not only not represented in government, they’ve been banned from most workplaces and from coeducational schools and universities. Even the Ministry of Women’s Affairs was shuttered and replaced with the ministry of vice and virtue, which has a history of publicly beating women for such minor “infractions” as what they wear or showing their wrists. In the coming year, the Taliban will reveal which side has won its internal disputes about the role of women in public life and their right to live free and full lives.

Carpenter: As I wrote in a World Politics Review column a couple of weeks ago, this situation of gender apartheid approaches crimes-against-humanity levels, when half a country’s population is relegated to their houses and threatened with violence if they appear in public or protest.

You have studied the role of gender in conflicts around the world. From what you’ve learned, are there actions women have taken to increase their own safety and rights? What advice would you give Afghan women now?

Carpenter: Those of us in the West must be careful not to essentialize “Afghan women.” They are not all the same: rural and urban women have experienced and want very different things, for example. Afghan women have a long history of standing up for their own rights. And the West has a long history of appropriating ‘women’s rights’ to serve their own geopolitical ends. At the same time, the reality is that many Afghan women would very much prefer help from the West and feel abandoned by the withdrawal. To some, it seems yet another case of women’s rights being subordinated to wider security concerns. What I argued in my recent column was that those Afghan women who choose to elicit help from the international community have the opportunity to liase as they’re able not just with Western aid organizations and human rights organizations but also with international judicial bodies such as the ICC.

Marks: Rather than giving advice to Afghan women, I’m trying to bear witness to and learn from the diaspora of Afghan women in exile who had to flee the country due to their work for gender equality, women’s rights, and more. I think the world has a lot to learn from them in terms of what they were able to achieve in the past 20 years, and also how the international community failed them as partners and allies. But, more importantly, they’re faced with the challenge of doing advocacy and activism from afar, with rapidly changing circumstances back home, along with the trauma and grief associated with years of war and displacement. In light of all that, perhaps the more important advice is to our own governments: to give Afghan women and LGBT rights advocates access to safety, security, mobility, and the right to employment so they can continue the important gender equity and women's rights work that forced them to flee the Taliban; and to remember the millions of women still carving out spaces for creativity, political expression, and recovery in the midst of a repressive regime.

What are some of the most effective actions advocacy groups can take to improve the situation for women in conflict areas?

Marks: I always think the single most important thing advocacy organizations can do is to open space for women or other underrepresented groups to have a seat at the table. Take the phrase “nothing about us without us” as a maxim and refuse to engage in peace talks, negotiated settlements, or brokered agreements about power and money without multiple women in the room. Women’s exclusion doomed previous peace talks with the Taliban, and frankly will doom the viability of the Taliban government in the long term. Not all women are feminists or gender equity advocates, but including a range of women’s voices in all processes is a prerequisite to women's gaining and maintaining human rights and political power.

Carpenter: An important action would be to speak to women and find out what they want in a nuanced way. The aid and advocacy community is not good at this, and often extrapolate ‘what women want’ from a very few select and usually elite ‘Afghan voices.’ A nuanced public opinion approach would be helpful to determine what the wider Afghan public wants, and how this breaks down by gender and other intersecting identity markers; but unfortunately the group conducting the best surveys in-country - Asia Foundation - has withdrawn due to security concerns facing its local staff. Another action advocacy groups can take is to identify local initiatives that are helping and find ways to support them.

How did you become interested and involved in researching the impacts of conflict on women and civilians in general?

Carpenter: I came to political consciousness while the war in ex-Yugoslavia was raging and this was, like many wars, a war against women’s bodies as well as against men and boys and ethnic groups. It wasn’t the first but it was the first that was televised in this way. It alerted me to the complexities of gender and conflict and helped urge me to look closely at these factors as I developed my understandings as a scholar. But gender, of course, is only one category of analysis among many in conflict zones, it affects men and boys as well as women and girls, and it is not always the most salient factor for women.

Marks: In southern Ethiopia many years ago, I had a striking conversation with a couple of pastoral women peace activists who described how young women would encourage their male peers to attack neighboring communities, and shame them if they refused. It was one of many important moments that turned my preconceived ideas about peace and conflict on their head. I realized not all women wanted peace, and in fact, that gender dynamics in political violence were terribly important and woefully under-researched. I began studying women's participation in rebel groups and insurgency, and increasingly, their influence on peace processes at the national and local levels. In the past decade, a thriving community of gender and conflict scholars has emerged, and I continue to discover new puzzles and important realities about the impact women's participation has on peacebuilding, social movements, and insurgency.

"Q&A with Zoe Marks and Charli Carpenter on Women in Afghanistan." Belfer Center Newsletter. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. (Fall 2021)