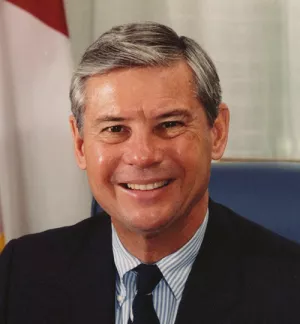

When the U.S. intelligence community released its October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) regarding Iraq and weapons of mass destruction, it had little idea that it would become the political hot potato of the 2008 presidential primaries. In recent Democratic and Republican debates, those candidates who were Senate and House members in 2002 were asked if they had read the NIE before casting their vote to go to war. Though each had access to the NIE before the vote, most had not. A NIE provides the highest level of analysis from the U.S. intelligence community. The president typically orders an NIE, but the head of national intelligence or the Senate and/or House intelligence committees can also direct its preparation. An NIE represents the collective view of the intelligence community - all 17 agencies gathered around the same table, each contributing everything it knows on the subject. While the NIE states a consensus view, each of the agencies is encouraged to offer reservations from or dissents to the majority opinion. The October 2002 NIE raised serious questions in my mind about some of the critical assertions supporting a pre-emptive war in Iraq. I became highly dubious about the credibility of the overall case for war. The NIE strongly influenced my vote against giving President Bush war-making authority in Iraq - one of only 23 such votes in the Senate. In order to understand the significance of the October 2002 NIE, it is first necessary to remember the events that preceded its release. The unprecedented terrorist attack of 9/11 was only a year in the past, and the Senate and House intelligence committees had spent much of those 12 months conducting a joint inquiry into pre-9/11 intelligence failures. While the retaliatory war against al-Qaida and the Taliban started well in October 2001, our effort in Afghanistan had bogged down as the campaign neared its first anniversary. With public concern still focused intensely on 9/11 and its aftermath, President Bush faced a major challenge in shifting that focus to the war he wanted to fight in Iraq. His trump card was a nightmare scenario: Saddam Hussein in possession of chemical, biological and/or nuclear weapons. As the drumbeats for war in Iraq grew increasingly loud in September 2002, the Senate intelligence committee, which I chaired, held a series of closed-door hearings to assess Saddam Hussein's threat to the United States. Members of our intelligence community provided a grim report. Iraq was producing or storing weapons of mass destruction in 550 sites across the country. The Iraqi military had installed missiles that could deliver a warhead more than 350 miles - enough to strike Israel. Saddam Hussein was developing an unmanned aircraft which could be launched from a ship at sea against a target in the United States. Iraq had the capability to unleash all of these capabilities on 45 minutes' notice. Most distressing, Saddam was reconstituting his nuclear program. With terrorist allies giving him access to enriched uranium, Iraq could produce a nuclear weapon within a year. With other members of the committee, I asked to see the NIE on three subjects: (1) the Iraqi program for weapons of mass destruction; (2) the likely battlefield scenario during an invasion; and (3) the plan for postwar U.S. occupation until sovereignty could be returned to a legitimate Iraqi government. Since NIEs were routinely prepared on subjects much less consequential than war, we were stunned when then-CIA director George Tenet told us that no NIE had been conducted on those subjects. When the intelligence committee used its legal authority to direct an NIE, Tenet resisted until strong committee pressure forced his hand. Even when Tenet finally agreed to an NIE, he insisted that it be limited to Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. In early October 2002, our committee received the classified version of the NIE. It was concise, approximately 90 pages in length. It had very high production values - photographs, satellite reconnaissance, graphs, maps and addresses. And it contained a majority consensus of the intelligence community: Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. The majority view was tempered by strong dissents. For example, as "proof" that Saddam was accelerating his nuclear program, the NIE cited aluminum tubes intercepted at the Iraq border to show he was assembling centrifuges for producing weapons-grade nuclear material. But the U.S. departments of state and energy - the latter of which oversees our nuclear program - insisted that the tubes were not technically usable for that purpose. There was unanimity on one issue. Every intelligence agency agreed that if Saddam had weapons of mass destruction, he would use them only if he were first attacked. When the classified NIE was presented to the Senate intelligence committee, I asked Tenet to identify the primary sources of his information. His answer - Iraqi exiles - sounded loud alarms in my mind. Many of the exiles had not been in Iraq for a decade or more. Since they would not return to Baghdad unless U.S. Army tanks were leading the way, they had selfish reasons to want a U.S. military invasion. With those doubts, I asked Tenet who in the U.S. intelligence community had verified the exiles' information. His chilling answer was the single most disconcerting moment of this entire sordid affair: nobody. The United States government had not invested even a single man hour to verify that Saddam's weapons of mass destruction program, including the alleged effort to produce nuclear weapons, was real and not a figment of the exiles' self-interested imagination. Alarmed, I tried to alert the public and instructed the intelligence agencies to produce a declassified version of the NIE. Intelligence officials usually declassify documents by drawing black lines through sensitive matters. In this case, we received a newly minted "declassified" NIE. It was 65 pages shorter. Gone was the debate over the aluminum tubes and any other dissents or reservations. Gone was the unanimous conclusion that Saddam would only use weapons of mass destruction if Iraq were first attacked. That was the last straw. The Bush administration was clearly scheming to manipulate public opinion in favor of war. I was livid. Five days later, during Senate debate on Iraq, I said that those who gave the president warmaking authority would have "blood on their hands." The purpose of this article is not to say I told you so or claim redemption for my vote. Far too many Americans and Iraqis have died to waste time on self-congratulations. But those nations who do not study history are doomed to repeat it. We have much to learn from the history of the October 2002 NIE. First, the United States must rapidly rebuild our human intelligence capability. While the officials who did not want to see the truth about Iraq were partially responsible for our prewar blindness, we also suffered from a shortfall of hands-on U.S. intelligence resources in Iraq. Unless the president and intelligence community immediately rectify this deficiency, the United States will lack accurate information about Iran, North Korea and other threats to our security. Second, U.S. intelligence community leaders must restore the tradition of speaking truth to power. In the months before the Iraq war, the Bush administration fostered an intelligence culture that valued subservience to the president's political agenda over the intellectually honest presentation of factual data. Those tactics have no place in a democracy, and our intelligence agencies must be ready to cry foul if another American president tries to make them part of an inaccurate public relations campaign. In my opinion, those candidates who voted for the Iraq war without first reading the NIE should not be disqualified from serving as president of the United States. For 220 years, Americans have held the office of the presidency and its occupants in high regard. With a few specific exceptions, we have generally presumed that presidents tell the truth in matters of war and peace. Any of the current presidential candidates could have honorably acted on that presumption in voting for the war in October 2002. But to use a phrase that President Bush once mangled, fool us once, shame on you. Fool us twice, shame on us. As voters closely evaluate potential presidents over the next 17 months, we must determine which candidates believe that the American people should be entrusted with the truth. More lies mean more lives lost around the world. Bob Graham was Florida's governor from 1979 to 1987 and a U.S. senator from 1987 to 2005. He served as chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence from 2001 to 2003 and is the author of Intelligence Matters. Graham currently leads the Bob Graham Center for Public Policy at the University of Florida and University of Miami. When the U.S. intelligence community released its October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) regarding Iraq and weapons of mass destruction, it had little idea that it would become the political hot potato of the 2008 presidential primaries. In recent Democratic and Republican debates, those candidates who were Senate and House members in 2002 were asked if they had read the NIE before casting their vote to go to war. Though each had access to the NIE before the vote, most had not. A NIE provides the highest level of analysis from the U.S. intelligence community. The President typically orders an NIE, but the head of national intelligence or the Senate and/or House Intelligence Committees can also direct its preparation. An NIE represents the collective view of the intelligence community - all 17 agencies gathered around the same table, each contributing everything it knows on the subject. While the NIE states a consensus view, each of the agencies is encouraged to offer reservations from or dissents to the majority opinion. The October 2002 NIE raised serious questions in my mind about some of the critical assertions supporting a preemptive war in Iraq. I became highly dubious about the credibility of the overall case for war. The NIE strongly influenced my vote against giving President Bush war-making authority in Iraq - one of only 23 such votes in the Senate. In order to understand the significance of the October 2002 NIE, it is first necessary to remember the events that preceded its release. The unprecedented terrorist attack of 9/11 was only a year in the past, and the Senate and House Intelligence Committees had spent much of those 12 months conducting a joint inquiry into pre-9/11 intelligence failures. While the retaliatory war against Al-Queda and the Taliban started well in October 2001, our effort in Afghanistan had bogged down as the campaign neared its first anniversary. With public concern still focused intensely on 9/11 and its aftermath, President Bush faced a major challenge in shifting that focus to the war he wanted to fight in Iraq. His trump card was a nightmare scenario: Saddam Hussein in possession of chemical, biological, and/or nuclear weapons. As the drumbeats for war in Iraq grew increasingly loud in September 2002, the Senate Intelligence Committee, which I chaired, held a series of closed door hearings to assess Saddam Hussein's threat to the United States. Members of our intelligence community provided a grim report. Iraq was producing or storing weapons of mass destruction in 550 sites across the country. The Iraqi military had installed missiles that could deliver a warhead more than 125 miles - enough to strike Israel. Saddam Hussein was developing an unmanned aircraft which could be launched from a ship at sea against a target in the United States. Iraq had the capability to unleash all of these capabilities on 45 minutes notice. Most distressing, Saddam was reconstituting his nuclear program. With terrorist allies giving him access to enriched uranium, Iraq could produce a nuclear weapon within a year. With other members of the committee, I asked to see the NIE on three subjects: (1) The Iraqi program for weapons of mass destruction; (2) the likely battlefield scenario during an invasion; and (3) the plan for post-war U.S. occupation until sovereignty could be returned to a legitimate Iraqi government. Since NIEs were routinely prepared on subjects much less consequential than war, we were stunned when then-Central Intelligence Agency Director George Tenet told us that no NIE had been conducted on those subjects. When the Intelligence Committee used its legal authority to order an NIE, Director Tenet resisted until strong committee pressure forced his hand. Even when Tenet finally agreed to an NIE, he insisted that it be limited to Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. In early October 2002, our committee received the classified version of the NIE. It was concise, approximately 90 pages in length. It had very high production values - photographs, satellite reconnaissance, graphs, maps, and addresses. And it contained a majority consensus of the intelligence community: Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. The majority view was tempered by strong dissents. For example, as "proof" that Saddam was accelerating his nuclear program, the NIE cited aluminum tubes intercepted at the Iraq border to show he was assembling centrifuges for producing weapons grade nuclear material. But the U.S. Departments of State and Energy - the latter of which oversees our nuclear program - insisted that the tubes were not technically usable for that purpose. There was unanimity on one issue. Every intelligence agency agreed that if Saddam had weapons of mass destruction, he would use them only if he were first attacked. When the classified NIE was presented to the Senate Intelligence Committee, I asked Director Tenet to identify the primary sources of his information. His answer - Iraqi exiles - sounded loud alarms in my mind. Many of the exiles had not been in Iraq for a decade or more. Since they would not return to Baghdad unless U.S. Army tanks were leading the way, they had selfish reasons to want a U.S. military invasion. With those doubts, I asked Tenet who in the U.S. intelligence community had verified the exiles' information. His chilling answer was the single-most disconcerting moment of this entire sordid affair: nobody. The United States government had not invested even a single man hour to verify that Saddam's weapons of mass destruction program, including the alleged effort to produce nuclear weapons, was real and not a figment of the exiles' self-interested imagination. Alarmed, I tried to alert the public and instructed the intelligence agencies to produce a declassified version of the NIE. Intelligence officials usually declassify documents by drawing black lines through sensitive matters. In this case, we received a newly minted "declassified" NIE. It was 65 pages shorter. Gone was the debate over the aluminum tubes and any other dissents or reservations. Gone was the unanimous conclusion that Saddam would only use weapons of mass destruction if Iraq were first attacked. That was the last straw. The Bush Administration was clearly scheming to manipulate public opinion in favor of war. I was livid. Five days later, during Senate debate on Iraq, I said that those who gave the president war-making authority would have "blood on their hands." The purpose of this article is not to say I told you so or claim redemption for my vote. Far too many Americans and Iraqis have died to waste time on self-congratulations. But those nations who do not study history are doomed to repeat it. We have much to learn from the history of the October 2002 NIE. First, the United States must rapidly rebuild our human intelligence capability. While the officials who did not want to see the truth about Iraq were partially responsible for our pre-war blindness, we also suffered from a shortfall of hands-on U.S. intelligence resources in Iraq. Unless the President and intelligence community immediately rectify this deficiency, the United States will lack accurate information about Iran, North Korea, and other threats to our security. Second, U.S. intelligence community leaders must restore the tradition of speaking truth to power. In the months before the Iraq war, the Bush Administration fostered an intelligence culture that valued subservience to the President's political agenda over the intellectually honest presentation of factual data. Those tactics have no place in a democracy, and our intelligence agencies must be ready to cry foul if another American president tries to make them part of an inaccurate public relations campaign. In my opinion, those candidates who voted for the Iraq war without first reading the NIE should not be disqualified from serving as President of the United States. For 220 years, Americans have held the office of the Presidency and its occupants in high regard. With a few specific exceptions, we have generally presumed that presidents tell the truth in matters of war and peace. Any of the current presidential candidates could have honorably acted on that presumption in voting for the war in October 2002. But to use a phrase that President Bush once mangled, fool us once, shame on you. Fool us twice, shame on us. As voters closely evaluate potential presidents over the next 17 months, we must determine which candidates believe that the American people should be entrusted with the truth. More lies mean more lives lost around the world. Bob Graham was Florida's governor from 1979 to 1987 and a U S. senator from 1987 to 2005. He served as chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence from 2001 to 2003 and is the author of Intelligence Matters. Graham currently leads the Bob Graham Center for Public Policy at the University of Florida and University of Miami.

Graham, Bob. “Rushing Past Warning Signs.” St. Petersburg Times, June 17, 2007

The full text of this publication is available via St. Petersburg Times.