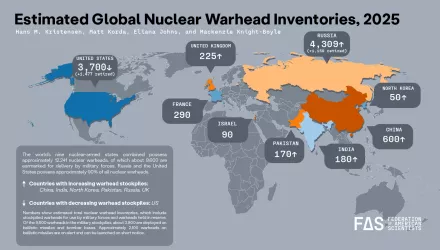

If the Vladivostok Agreement of November, 1974, is transformed into a treaty, we will have reached a turning point in the long, tortuous, frustrating effort to bring strategic nuclear weapons under control. This turning point will not necessarily be a breakthrough, however; no substantial controls on existing or planned strategic weapons systems will have been accomplished. Still, some essential steps have been taken: The issues of forward-based systems, of asymmetries in the throw-weights of missile forces on either side, of strategic compensation for the British and French nuclear-armed submarines, and for the alleged geographical disadvantages of the Soviet Union have been resolved in the process of arriving at agreements on equal ceilings for the number of strategic delivery systems and the number of missiles that can be MIRVed (i.e., fitted with multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles). The large numbers proposed for these ceilings allow the continuing development and deployment of most of the weapons systems now being planned by the two sides; only after these ceilings are reached will the limits begin to be felt, unless the present agreement is modified. Consequently, the agreement does not in itself constitute timely and visible progress in arms limitation. Clearly it was a disappointment for those who thought or hoped that the time had come for such an achievement. But it does provide for the elimination of several persistent obstacles to significant limitations and for a framework within which these limitations can be negotiated.

In addition, about a dozen other treaties negotiated over the last twelve years limit the nuclear-arms competition in various ways. The 1963 treaty, banning all but underground nuclear-weapons testing, and the 1972 ABM treaty were particularly important for introducing the two leading nuclear powers to the practice of verified restraint and the benefits to be derived from it.

Doty, Paul. “Strategic Arms Limitation After SALT I.” Daedalus, Summer 1975