IN TUESDAY evening's State of the Union speech, President Bush defended his warrantless wiretap program by giving one example of where it might have saved American lives: "It is said that prior to the attacks of Sept. 11, our government failed to connect the dots of the conspiracy. We now know that two of the hijackers in the United States placed telephone calls to Al Qaeda operatives overseas. But we did not know about their plans until it was too late."

Vice President Dick Cheney made a similar assertion three weeks ago. Both refer to two of the 19 hijackers who lived in San Diego in 2000: Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Midhar. In these two sentences the president has committed two sins. He has stretched the truth, and he has distracted the American people from the steps we need to take to truly make us more secure from terrorist attacks.

During the Joint Inquiry of the Congressional Intelligence Committees, which I cochaired, we determined the following to be some of the major failures involving the San Diego two: In December 1999, the CIA was alerted that a summit of terrorists would be held at Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and that two Saudis, Hazmi and Midhar, would participate.

The Kuala Lumpur CIA station decided to outsource the surveillance of the summit to Malaysian intelligence, which was unable to place a listening device in the meeting room. Had it done so, we probably would have heard of Al Qaeda's plans to attack a US destroyer, which in October 2000 culminated in the bombing of the USS Cole, and the initial preparations for 9/11.

In January 2000, deaf but not blind, the CIA had secured photographs of all the summit participants and the US visa of Midhar. None of this information was included in the State Department's watch list of suspect persons, and neither immigration and border control agencies nor the FBI were notified. Two weeks after the summit ended, the two future hijackers entered the United States through Los Angeles International Airport undetected.

By March 2000, the CIA also had information indicating that Hazmi had traveled to Los Angeles, but information about the travel of either man was not given to the FBI until late August 2001.

By June 2000, the two Saudis who had been living in San Diego for five months were boarders in the home of Abdussattar Shaikh. Hazmi listed his number in the San Diego telephone directory. Unknown to them, Shaikh was a paid informant of the FBI, assigned to oversee and report on the activities of young Muslims in San Diego.

Because the FBI did not know of the CIA's information on Midhar and Hazmi, Shaikh was not tasked to keep an eye on the two. Shaikh's handling agent testified that, had he known that the CIA had identified the two as Al Qaeda operatives, he would have done a "full court press" in terms of surveillance, informant tasking, and investigation — and believes he could have uncovered the plot and potentially foiled the 9/11 attacks.

According to the San Diego Union Tribune, the director of the FBI office in San Diego stated that the fundamental mistakes were a failure of his agency and the CIA to communicate. "If we knew what the CIA knew, we'd have been in an ideal situation to locate these people." He made no suggestion that by following the law, securing a search warrant before wiretapping, was a detriment.

It is wrong to suggest that the events of 2000 justify warrantless eavesdropping. Just the opposite. It is by correcting institutional and personal incompetence, rather than sacrificing the rights of Americans, that our safety can be best secured.

Through the Patriot Act, passed in 2001 after the 9/11 attacks, Congress modified or repealed laws that had constrained the sharing of information between law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Other critical changes remain — neither of which was mentioned in the president's speech.

The FBI must install an information technology that will modernize its antiquated internal and external communications, and the intelligence community must recruit and train an adequate staff of culturally sensitive Middle Eastern and Central Asian linguists to serve as agents and analysts.

These are two of the steps that will make us safer. These changes will bring us closer to achieving the president's optimistic conclusion: "We will renew the defining moral commitments of this land. And so we move forward — optimistic about our country, faithful to its cause, and confident of the victories to come."

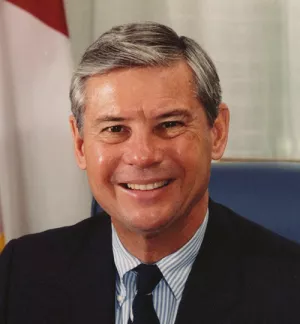

Bob Graham, a former Florida senator, is a senior fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Graham, Bob. “The Truth behind the San Diego Two.” The Boston Globe, February 5, 2006