Development is easier done than said. This inversion of the old maxim reflects the end of an era in which Africa's development was defined largely as a matter for discourse rather than accomplishment.

The traditional focus on relief and emergency activities is being replaced by a new focus on competence building to enable Africa solve its own problems.

In a crucial statement about the future of Africa, Our Common Interest — the report of the Commission for Africa chaired by UK Prime Minister Tony Blair — notes: "Growth will also require a massive investment in infrastructure to break down the internal barriers that hold Africa back. Donors should fund a doubling of spending on infrastructure — from rural roads and small-scale irrigation to regional highways, railways, larger power projects and Information & Communications Technology (ICT)."

Investing in infrastructure is emerging as a critical item on Africa's sustainable development agenda.

This interest has been inspired by the growing recognition of the role of infrastructure in sustainable development. It has also been reinforced by the demand for adequate infrastructure in the rapidly expanding urban areas.

In 1980, for example, only 28 per cent of the African population lived in cities. Today the figure stands at about 37 per cent. Africa's annual urban growth rate is 4.87 per cent, twice that of Asia and Latin America. This makes Africa the fastest urbanising continent in the world.

Demand for infrastructure

African countries inherited a highly dispersed and unevenly distributed infrastructure from the colonial period. Colonial development strategies focused solely on connecting natural and mineral resources to ports for export markets. They failed to integrate the continent or stimulate local industrial development.

Africa's demand for infrastructure across sectors is hardly being met for the majority of people, with its worst sectoral performance being in access to electricity. Even where such access exists, supply is unreliable and the quality of services remains poor.

Generally, access to infrastructure services favours the rich and is more unequal in Africa than in any other part of the world. In some cases infrastructure projects may perpetuate historical inequities. There are major disparities in access to clean water in urban settings. Of Africa's 280 million urban residents, over 150 million lack access to clean water and nearly 180 million do not have adequate sanitation.

For example, some 48 per cent of African urban households have a water connection, compared to only 19 per cent of informal settlements. Similarly, 31 per cent of urban households are connected to the sewerage system, but the figure for informal settlements is 7 per cent.

There is good news, however: the advent of ICTs is transforming the continent. In 2001 Uganda became the first African country where mobile phones exceeded land fixed lines. The market has expanded from under 20,000 users in Africa in 1993 to an estimated 18.2 million in 2003. But despite such phenomenal growth rates, much of Africa still remains disconnected from the rest of the world because of poor communications infrastructure.

Access to high bandwidth services remains beyond the reach of most individuals and institutions.

Similarly, prospects for enhancing private sector participation through improved telecommunications are being undermined by poor infrastructure.

Transportation costs in Africa are the highest of any region in the world. With landlocked countries having to figure in transport costs of up to 75 per cent of the value of their exports, the continent faces extreme challenges to compete in global markets.

In Uganda, for example, transport costs add the equivalent of an 80 per cent tax on clothing exports.

Freight charges for imports are 70 per cent higher in West and East Africa than in Asia. Africa's landlocked countries pay more than double the rate of Asian countries for comparable transport services.

Most of Africa is isolated from major air and maritime routes, which allows access only to high-cost, peripheral routes. More than 20 per cent of African exports reach the United States by air. It is estimated that air transport costs account for up to 50 per cent of the value of exports to the United States. Internally, air transport costs across Africa are up to four times the cost of getting the same goods over the Atlantic.

Private sector participation

A loss of focus on the importance of economic growth in poverty reduction and a failure to appreciate the importance of infrastructure investment led to a drop in infrastructure spending in Africa.

Development policy in the 1980s and 1990s asserted that infrastructure would now be financed by the private sector.

From 1990 to 2002 infrastructure investment in Africa stood at US$150 billion, of which only US$27.8 billion came from the private sector. Nearly two-thirds of this amount (US$18.5 billion) was for telecommunications.

Unfortunately, private sector participation in infrastructure investment has not taken off in Africa, contrary to policy opinion. Over an almost 20-year period, Africa has only managed to generate 230 projects in partnership with foreign operators, about half of which are located in South Africa.

Irrespective of the South African bias of the data, the total number of projects is small and so is the average size of projects in Africa.

The average project size is indeed less than half of that in other developing countries. Africa's share of total (mostly foreign) private investment attracted by infrastructure across all sectors in the developing world is roughly 1–2 per cent (except in telecoms, 6 per cent).

Additional funding approaches now include private-public partnerships such as the Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund set up by the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG). The group was founded in 2002 by the UK Department for International Development (DfID), the Swedish International Development Co-operation Agency, the Netherlands Ministry for Development Co-operation, and the Swiss State Secretary for Economic Affairs.

The war-torn economies in Africa are perhaps the hardest hit by the inadequate provision of infrastructure services, where physical infrastructure stocks (e.g., telecommunications, airports, ports, roads, and bridges) are often key targets during war. Although only a fraction of a country may be directly affected by war, infrastructure investment and maintenance is neglected in favour of military expenditures.

Africa is highly vulnerable to external shocks arising from natural disasters such as cyclones, floods, droughts, and earthquakes. The economic fragility arising from natural disasters often deepens precarious economic and social situations. Natural disasters tend to divert a large portion of government and donor resources from otherwise essential infrastructure investment to emergency relief operations. But natural disasters can also serve as a stimulus for investing in engineering for disaster preparedness. Disaster management could therefore serve as a foundation for building expertise in ecological engineering.

An equally important dimension in Africa's future is the possible impact of climate change on infrastructure development. Africa's high rate of urbanisation is partly reinforced by declines in rainfall in parts of Africa. These trends suggest that African countries will need to invest in technologies needed for adapting climate change, most of which will involve the use of a wide range of engineering capabilities.

Contemporary development history offers a wide range of lessons on the role of engineering in sustainable development in general and technological innovation in particular. These lessons range from the role of technical universities in economic reconstruction to business incubation. Africa and its international development partners can benefit considerably from these experiences.

In Rwanda, for example, after the 1994 genocide destroyed much the country's physical infrastructure and skill base, the country's reconstruction efforts have been associated with high-level emphasis on engineering. This is illustrated by Rwanda's decision in 1997 to convert the premises of a military academy into a base for a new technical university, the Kigali Institute of Science, Technology and Management (KIST). The evolution of KIST represents an interesting example of the role of international development co-operation in building engineering competence in Africa.

Technology transfer

As foreign participation in infrastructure projects in Africa increases, the issue of technology transfer in infrastructure development becomes even more important. Empirical evidence on technology transfer suggests that government policies regarding the types of contracts stipulated for infrastructure construction can influence the degree of technology acquisition by a developing country.

The construction industry in Algeria is a good example. Since the 1970s, the construction industry has been considered as one of the "industrialising industries," which is expected to generate a large part of employment and contribute to the GDP.

The government initially encouraged the purchase of complex and advanced, though costly, systems of technology from foreign firms. Sophisticated and highly integrated contracts, such as turnkey and product-in-hand contracts, were used to assemble and co-ordinate all the project operations, from conception through implementation to installation, into one package. The aim was to transfer the entire responsibility to the foreign technology supplier.

These types of contracts did not lead to as much technology transfer as the government hoped. Having learned from past failures, the Algerian government later supported "decomposed" or "design and installation supervised" contracts, under which infrastructure projects were more fragmented and involved more local firms than under the integrated contracts. This approach reduced uncertainty in implementation and facilitated the accumulation of technological capabilities in local firms through learning-by-doing. The approach also contributed to the development of investment and managerial capability of local managers.

In many African countries, reorienting universities to play a greater role in the development of their countries has to take centre-stage. They can accomplish this by strengthening their entrepreneurial activities, as well as by supporting national projects, industry, and other centres of excellence.

In 1990, the director of the computer centre at the University of Zambia (UNZA) connected a few personal computers to exchange emails within the institution, with Rhodes University in South Africa, and then with the rest of the world. The university network grew to serve national health institutions, non-governmental organisations and other development agencies. In 1994, Zambia became the first sub-Saharan country outside South Africa to connect to the Internet.

The university decided to establish a campus-based company called Zamnet Communication Systems to provide service to the university as well as to commercial customers. At this point the World Bank expressed an interest in covering 80 per cent of the operating cost of the first year. It lent Zamnet the start-up capital, on condition that the university would offer some shareholding in the unit to the public.

Seven months before the lapse of the World Bank loan, Zamnet was generating enough income to buy new equipment.

Building new universities

The role of the private sector in supporting training in engineering is a subject of extensive policy debate. Much of the attention has focused on the extent to which the private sector provides market signals for higher education. Little attention, however, has been devoted to the role of the private sector as an incubator of universities.

South Korea's Pohang University of Science and Technology (Postech), founded in 1986, offers important policy lessons for the engineering community. It is a product of two innovators: Professor Hogil Kim, the founding president of Postech, and Tae-Joon Park, the chair of the Pohang Iron and Steel Company (Posco). These two had the goal of setting up a leading research university in South Korea.

The university started off with a small number of outstanding students who were fully funded and drawn from the top 2 per cent of high school graduates. In 1987 Postech admitted 249 students into nine science and engineering departments. It admitted its first graduate students the following year.

Posco's research facilities were transformed into an independent Research Institute of Industrial Science and Technology and served as a joint arm of the university and the company, making it a model university-industry partnership. Postech places heavy emphasis on research and is emerging as a leader in science and engineering education in Asia.

Emulate South Korea model

The one major lesson that Africa can take from this case is the role that Posco, a private company, played in developing Postech. Posco's initial goal was to train world-class engineers for its operations.

It shows that private companies in Africa might successfully support higher education not only for their benefit but also for national economic development. Africa already has several well-established industries that rely heavily on innovations in science and technology that could emulate this model.

Although the costs involved in the creation of Postech are currently well beyond the means of most African countries, the model still has the potential to be applied to a variety of fields.

Telecommunications firms, for example, that have benefited from the cell phone revolution could explore the possibility of creating leading information and communications schools using Postech experiences. Similarly, mining, oil and gas, tourism, and agriculture firms can serve as sources of new innovations in their respective fields.

These cases underscore the important role that investment in engineering can play in society. They also represent a wide range of practical models available both to African countries and their development partners for broadening and building engineering capacity for sustainable development. But such efforts need to be placed in the appropriate national and regional policy contexts.

While it is prudent for Africa to emphasise international trade, doing so requires greater investment in developing capabilities to trade, including technological innovation, development of business and human resources, and institutional strengthening. The impact of larger markets on technological innovation, the economies of scale, and the diffusion of technical skills arising from infrastructure development are among the most important gains Africa could obtain from regional integration.

There is momentum in African regionalism that is characterised by deliberate efforts to design and implement plans for the application of engineering to sustainable development. Co-operation in engineering can take various forms, including joint projects, information sharing, conferences, building and sharing joint laboratories, setting common standards for research and development, and exchange of expertise.

Some African countries are already endowed with robust science and technology infrastructure, which could easily be utilised by less well-equipped countries. New regional initiatives will need to emphasise the use of science and innovation in their sustainable development strategies.

Bringing engineering to the centre of Africa's economic renewal will require more than just political commitment: it will need positive executive leadership. This challenge requires "concept champions" who in this case will be heads of state spearheading the task of shaping their economic policies around science and innovation.

Quality executive leadership in these areas will depend on how well political leaders are informed about the role of engineering in sustainable development. Advice on science and innovation needs to be part of the routines of policymaking. An appropriate institutional framework needs to be created for this to happen. Many of the African cabinet structures are a continuation of the colonial model that was structured to facilitate the control of local populations rather than to promote economic transformation.

So far, most African countries have not developed national policies that demonstrate a sense of focus to help channel available technologies into solving developmental problems. They still rely on generic strategies dealing with poverty alleviation, without serious consideration of the sources of economic growth.

Engineering capabilities

Successful implementation of science and innovation policy requires civil servants to have policy analysis capacity (which most civil servants currently lack). Training diplomats and negotiators in policy aspects of engineering can also increase their capacity to handle technological issues in international forums.

Building competence in science and innovation policy will require investment in specialised courses of study and degree programmes on the subject. This could be accomplished by graduate schools of science and innovation policy that can then co-operate with similar programmes in other countries through a variety of training programmes.

A key strategy in building up engineering capabilities in Africa is to link training programmes to infrastructure projects in growing fields. For example, the expansion of ICT infrastructure provides unique opportunities for setting up training programmes in electronic engineering. Similarly, expansion of power supply facilities could be used as a platform for creating linkages with training facilities in electrical engineering and related fields.

Solving Africa's pressing challenges, therefore, will require concerted effort and close collaboration among governments, industry, academia, and civil society. It will also involve experimentation and the willingness to risk failure. And there will be failure. But success will depend on a willingness to learn on the part of all development partners: It is only through experimentation and learning that we can reduce the costs of errors and enhance the benefits of innovation.

The G8 nations have agreed to invest more in better education, extra teaching and new schools, and to help develop skilled professionals for Africa's private and public sectors by supporting networks of excellence between Africa's and other countries' institutions of higher education and centres of excellence in science and technology.

But this will not happen unless there is complementary leadership in Africa to put science, technology and innovation at the centre of the sustainable development process. In a timely move, the African Union will devote its January 2007 presidential summit on "scientific research and technology for socio-economic development". The outcomes of the summit and follow up activities will be decisive is creating a strong basis for forging international partnerships on engineering for sustainable development.

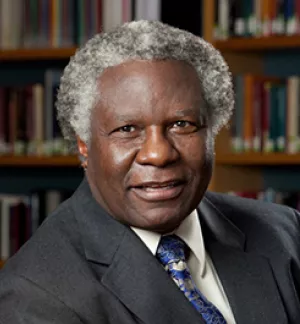

Calestous Juma is Professor of the Practice of International Development and Director of the Science, Technology and Globalisation Project at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government. This article is adapted from his 2006 Hinton Lecture at the Royal Academy of Engineering, London, delivered on October 3.

Juma, Calestous. “We Must Redesign Our Economies for Take-Off.” The Daily Nation, October 27, 2006