About This Report

This report is based on the results of a two-day workshop hosted by the Belfer Center’s Arctic Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School on November 6-7, 2025. The workshop brought together experts from environmental, technical, academic, policy, and legal fields, as well as representatives of Arctic Indigenous communities, to consider a range of issues affecting the Arctic Ocean and to develop actionable recommendations for policymakers and practitioners.

The workshop focused on current and likely future threats to biodiversity in the Arctic Ocean arising from climate change and the prospect of increasing industrial activity that may occur as the region continues to grow warmer. Participants reviewed efforts to address these challenges at the local, national, and circumpolar levels with a view to deriving “lessons learned” from such efforts and determining how successful initiatives might be scaled up or adapted for use in other parts of the Arctic.

To facilitate a free flow of ideas, the workshop took place under the Chatham House Rule. The discussions did not seek to reach consensus among participants on the issues under discussion, but rather to generate a menu of recommendations for consideration and use by governments – individually and collectively – and by practitioners concerned with the Arctic Ocean and its biodiversity.

The Belfer Center gratefully acknowledges the support and partnership provided by a number of environmental organizations and Arctic Indigenous groups who contributed to the organization of the workshop. The Belfer Center also offers its appreciation to the Representation of the Faroe Islands in Washington, D.C., and expresses the hope that this report will contribute to successful events relating to the Arctic Ocean that will take place in Tórshavn in May 2026.

Overview of the Workshop

To set the scene, participants received presentations on the state of the Arctic’s climate and on the need for full engagement of Arctic Indigenous Peoples on matters affecting the Arctic Ocean. This included a preview of two closely connected Arctic events scheduled for the Faroe Islands next year: the UArctic Congress and Assembly as well as the Ocean Connectivity Conference that will take place under the auspices of the Arctic Council, and will provide further opportunity to further discuss challenges relating to Arctic ocean governance.

The workshop next considered examples of available tools and frameworks for securing biodiversity conservation and cultural and ecological resilience in the Arctic Ocean, based on presentations from the Aleut International Association, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, and the WWF Global Arctic Programme. Participants also reviewed the prospects for using the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement to advance conservation efforts in the Arctic. That treaty will enter into force in early 2026.

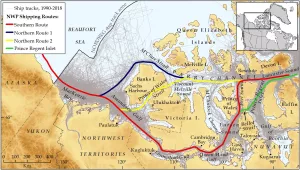

The next segment of the workshop examined a range of current and emerging/potential industrial activities in the Arctic Ocean, including commercial shipping, oil and gas development, and seabed mining. In reviewing these matters, participants considered the legal and policy frameworks that exist for mitigating the adverse effects of these industrial activities on Arctic Ocean biodiversity, including through the International Maritime Organization, the Arctic Council, and the International Seabed Authority.

The final set of presentations related to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement. Participants considered several valuable aspects of this agreement, especially the way it embodies the precautionary approach in creating a moratorium on high seas fisheries, how it guarantees the involvement of Arctic Indigenous representatives and the use of Indigenous Knowledge, and the fact that in-person meetings among all ten parties to implement the Agreement have taken place regularly following its entry into force in 2021.

The balance of the workshop was devoted to in-depth discussions seeking to develop recommendations to address the challenges to biodiversity conservation in the Arctic Ocean at various levels and through a range of international institutions. The sections below offer the resulting recommendations targeted to policymakers.

Recommendations for Policymakers

Participants in the workshop acknowledged that the current geopolitical environment relating to the Arctic Region is presenting significant obstacles to international cooperation. Engagement with the Government of the Russian Federation remains very limited in the wake of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war there. In addition, policy shifts by the United States Government suggest a growing divergence with most other Arctic governments on issues relating to climate change and biodiversity conservation.

Despite these obstacles, it is incumbent on policymakers to find ways forward in addressing a range of urgent challenges confronting the Arctic Ocean and its ecosystems. The workshop considered a wide range of possible steps and generated the following specific recommendations.

- Scale up successful Arctic initiatives, including those developed at the subregional level, and adapt the lessons learned from those initiatives for use in other parts of the Arctic. In recent years, governments, Indigenous Peoples organizations, and nongovernmental organizations have worked together to develop and implement a range of initiatives to address Arctic Ocean concerns. While an exhaustive listing of these efforts is beyond the scope of this report, the workshop considered several successful examples that have the potential to be scaled up or replicated in useful ways.

- The SINAA Agreement, adopted pursuant to the Project Finance for Permanence initiative in Canada, seeks to advance marine and terrestrial stewardship and coastal economies in the Canadian Arctic. Led by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, the SINAA Agreement will also contribute to Canada’s goal of conserving 30 percent of Canada’s oceans by 2030 through the establishment of new marine protected areas and other measures.

- The Arctic Council’s Working Group on Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) recently updated its Framework for a Panarctic Marine Conservation Network. The Framework, part of PAME’s broader MPA-Network Toolbox, offers policymakers a range of options for addressing biodiversity challenges in the Arctic Ocean.

- Established in response to a proposal from Alaska Native communities, the Northern Bering Sea Climate Resilience Area protected a large swath of the Bering Sea from potential hydrocarbon development and launched a partnership between those communities and the United States Government to address a broader range of regional challenges. Although the work is presently on hold, the initiative offers a useful model for collaboration.

- Arctic Watch is a public-private partnership that focuses on monitoring and managing ship traffic through the Bering Strait and adjacent Arctic waters to enhance maritime safety, protect wildlife and ecosystems, and safeguard the subsistence and cultural practices of Indigenous communities.

- ArcNet – an Arctic Ocean Network of Priority Areas for Conservation – is WWF’s science-based tool to identify priority areas for conservation in the Arctic Ocean that meet the conservation needs of marine life and maintain the key functions of the region’s unique and interconnected ecosystems, It provides a mapped blueprint and starting point for governments, marine stakeholders, and rights holders to discuss and advance area-based marine conservation across the Arctic region.

- In designing and implementing initiatives in the Arctic Region, involve Arctic Indigenous communities at all stages and incorporate Indigenous Knowledge wherever possible. The Arctic is the homeland of Arctic Indigenous Peoples, a place where they have lived and provided stewardship over the land, the ocean, and Arctic resources for countless generations. For these and other reasons, policymakers are duty-bound to involve Arctic Indigenous communities in all matters affecting them.

- Respect the rights of Arctic Indigenous Peoples consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- Honor the admonishment on the involvement of Arctic Indigenous Peoples reflected in the phrase “Nothing About us Without Us.”

- Broaden the range of co-management initiatives and efforts to co-produce knowledge.

- Follow the Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement adopted by the Inuit Circumpolar Council.

- Pursue a precautionary approach to the expansion of new and existing industrial activities in the Central Arctic Ocean. Using the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement as a model, seek agreement among nations to apply precautionary management to transpolar commercial shipping, potential seabed mining, and other human activities that could adversely affect Central Arctic Ocean ecosystems.

- Use this precautionary approach to advance actions necessary to reduce risks and inform future decision-making regarding industrial activities in the Central Arctic Ocean, including through targeted scientific research and monitoring.

- Consistent with Recommendation 2, above, involve Arctic Indigenous communities in the design and implementation of precautionary measures and management frameworks.

- Consider the development of a long-term governance mechanism for the Central Arctic Ocean grounded in coordinated scientific research and science-based decision-making to support effective ecosystem-based management.

- Allow the Arctic Council to resume more robust operations. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Arctic Council has stopped meeting at the Ministerial and Senior Arctic Official levels. Arctic Council Working Groups are only meeting virtually. Although the Arctic Council is still undertaking useful projects and programs, its effectiveness could be enhanced in a number of ways without returning to “business as usual” vis-à-vis the Russian Federation.

- Permit Arctic Council Working Groups to resume in-person meetings, including with the participation of technical experts from Russia.

- Make maximum use of tacit approval processes to advance project and program work.

- Provide greater support to facilitate the involvement of Permanent Participants.

- Seek renewed engagement from Arctic Council Observers, including in the advancement of new project proposals.

- Expand implementation of the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement and the Arctic Marine Oil Pollution Agreement through additional joint training, joint exercises, and information exchange.

- Encourage the current Arctic Council chairship to work with the next two incoming chairships to plan for long-term projects and a potential return to full functionality of the Arctic Council.

- Work through the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to secure additional measures relevant to the Arctic Ocean. Although its procedures are time-consuming and have recently become politicized, the IMO and its Member States can take a range of actions to strengthen management of shipping in the Arctic Ocean.

- Improve Polar Code enforcement vis-à-vis non-compliant vessels.

- Develop and implement voyage planning requirements under Chapter 11 of the Code; make Arctic area-specific biodiversity data (including on mammal migration corridors) available to mariners.

- Revive efforts to adopt the NetZero Framework and other clean fuel initiatives to accelerate decarbonization in the shipping sector.

- Consider a phase-out of single-hulled tankers in the Arctic Ocean (and potentially worldwide).

- Update the guidelines relating to Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas to enhance conservation benefits.

- Advance vessel traffic management through Arctic Ocean chokepoints such as the Bering Strait.

- Recognize and support the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC)’s permanent consultative status as a means to incorporate Arctic Indigenous perspectives and Indigenous Knowledge into IMO actions concerning the Arctic Ocean.

- Make strategic use of global regimes and initiatives to advance biodiversity conservation in the Arctic Ocean. Issues concerning the Arctic Ocean relate in multiple ways to issues playing out at the global level. Below are just a few examples of global regimes and initiatives that policymakers can apply to propel work in the Arctic Ocean forward.

- Leverage the commitments set forth in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework to advance Arctic marine protection, particularly in light of the fact, by most measures, only slightly more than 5% of the Arctic Ocean is protected.

- Consider the development of a Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment for the Central Arctic Ocean under the rubric of the BBNJ Agreement, building on the Ecosystem Assessment of the Central Arctic Ocean. A Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment would advance the goal of precautionary planning while also laying needed groundwork for renewed circumpolar cooperation.

- Use preparations for the International Polar Year 2032-2033 to renew joint science cooperation and to advance Arctic Ocean biodiversity, including with Russian scientific institutions.

Conclusion

As noted above, the geopolitical circumstances of the Arctic are particularly challenging at present. Policymakers can nevertheless make use of the current period to advance efforts to tackle the problems confronting the Arctic Ocean, drawing on the menu of recommendations presented in this report. In doing so, they can engage more actively with civil society organizations, the private sector, and youth groups. Policymakers can also prepare for time when the geopolitical situation may improve, particularly by considering ways to restart cooperation with the Russia Federation on mutually beneficial initiatives when the time is right.

Balton, David. “Arctic Ocean Governance: Workshop Report and Recommendations for Policymakers.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 17, 2026