The legal status of the Northwest Passage: International strait or internal waters of Canada and Inuit Nunangat?

The international legal status of the Northwest Passage remains unresolved. Canada maintains that the Passage lies within its internal waters, under full Canadian sovereignty. Whereas the United States has taken the position that it is an international strait, through which foreign vessels can transit freely without Canadian consent.

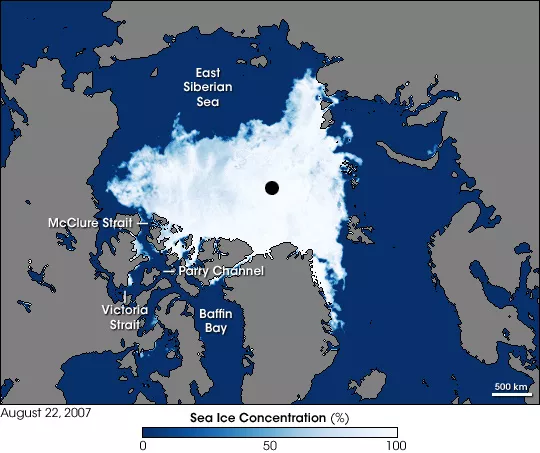

The U.S. Argument for an International Strait: The United States asserts that the NWP qualifies as an international strait under Article 37 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), arguing that the NWP connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and thus must be treated as a strait with a right of transit passage for all nations. The U.S. position on international straits is that they do not depend on a waterway being ice-free or frequently used historically – if a passage connects two high seas/exclusive economic zone (EEZ) areas, it can be considered an international strait subject to transit rights. The United States has never accepted Canada’s historic waters claim and regularly reasserts that the Passage is an international waterway.

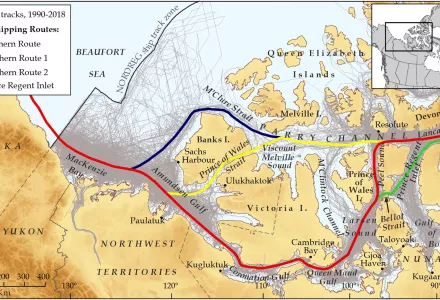

The Canadian Argument for Internal Waters: Canada’s position is that the NWP lies entirely within Canada’s territorial waters. In 1985, Canada drew baselines around its Arctic Archipelago that define the outer limit of Canada’s historic internal waters. Canada asserts that it has full sovereignty over the “historic internal waters” winding through the islands of the Arctic Archipelago that is based on historical exploration and effective governance of these waters. As part of this assertion, Canadian officials have emphasized that from time immemorial Inuit have used and occupied the waters and sea ice between these islands “as they have used and occupied the land,” which for Canada, strengthens its historic title.

Inuit – Historic Use and Indigenous Rights: Inuit in Canada emphasize that the NWP is inseparable from their homeland, Inuit Nunangat, and must not be regarded purely as an external or strategic waterway, necessitating legal recognition of Indigenous rights and Inuit-led co management in any governance or policy framework. Inuit assert that their continuous presence for millennia and relationship with the local environment establishes both ancestral rights and stewardship responsibilities. The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) Canada has argued that the U.S. position is inconsistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), noting that Inuit have rights to the lands, waters, and ice they have “traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.” This position is based on treaties and constructive agreements between Inuit and the Government of Canada, including the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement among others, that “recognize both Inuit sovereignty and Canadian sovereignty over the Arctic, including the Northwest Passage.” The Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami’s (the national representation organization for Inuit in Canada) Nilliajut 2 report asserts that Inuit voices are essential in defining the Passage’s future, stating that “we must be consulted before any decisions are made and any research is done.”

Perspectives from Russia and China: Russia’s interpretation mirrors Canada's, which is central to its sovereign control over the Northern Sea Route. Parallels have also been made between the NWP debate and China’s claim that the Qiongzhou Strait in the South China Sea is part of China’s internal waters, an assertion that the United States formally rejects. However, the Chinese government has never explicitly recognized the Canadian position. China, as a self-proclaimed “near-Arctic state,” has been more cautious and ambiguous, formally respecting Arctic states’ jurisdiction but emphasizing international law and freedom of navigation as it pursues its “Polar Silk Road” across the Arctic.

Agree to Disagree? The U.S.-Canada 1988 Arctic Cooperation Agreement: Two diplomatic incidents - the transiting of the NWP by the U.S. tanker SS Manhattan in 1969 and the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Sea in 1985 - sparked strong public and political reactions in Canada. In both instances, despite important contexts unique to each case, the United States did not formally request permission but coordinated with Canada throughout the passage.

To manage tensions, the two countries signed the 1988 Arctic Cooperation Agreement: the United States would notify Canada of voyages of American icebreakers conducting research while transiting the NWP without officially asking for permission, and Canada would grant consent routinely without the United States officially asking for it. The deal preserved both sides’ legal positions while serving as a model for Ottawa and Washington to manage the NWP disagreement. This has been described as a pragmatic “agree-to-disagree” framework that eased tensions but left the underlying legal debate unresolved.

For now, the official line on both sides remains unchanged. Some observers have proposed that the two nations find a mutually beneficial resolution (for instance, a joint management regime that acknowledges Canadian legal control while assuring innocent passage to foreign ships). Other experts feel that any negotiation could risk one side’s core interests, and that the existing compromise, ambiguous as it is, has worked without major incident. This longstanding debate has been generally well-managed, and so far, poses “no acute sovereignty or security concerns to Canada.”