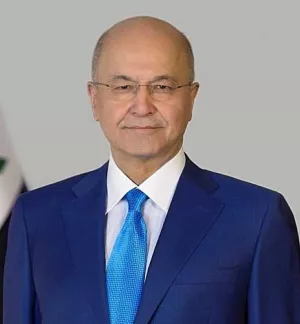

During the Fall 2025 semester, the Belfer Center and the Middle East Initiative (MEI) convened a four-part study group at the Harvard Kennedy School on identity and politics in the Middle East. The group was led by H.E. Dr. Barham Salih, Senior Fellow at the Belfer Center, and Dr. David Siddhartha Patel, Visiting Scholar at the Belfer Center's Middle East Initiative.

The group focused on how states in the contemporary Middle East try to manage ethnic, religious, and linguistic pluralism: sometimes through constitutions, courts and legal rules; often through informal bargains that never make it onto paper.

Session 1: Diversity and States in the Middle East

The opening session built a shared baseline around the question: what is “identity” in practice? Dr. Patel emphasized a point that sounds obvious, but is routinely ignored: people do not have one single identity, they have many possible ones. He made a distinction between identity groups (e.g., Sunni, Arab, Syrian) and the categories those groups fit within (e.g., sect, native language, country of origin). Politics often works by activating some identity categories over others.

This framing helped clarify a second point: diversity is not automatically a predictor of conflict. Identity can be real and consequential without being the root cause of violence. It can be used as a banner or as an excuse – but it can also be used as a tool for coalition-building.

Dr. Patel used Arab nationalism as an illustration. This project was powerful in the age of decolonization, but it failed to produce durable regional political unity. Instead, more concrete state nationalisms took precedence, and these nationalisms themselves still contain wide internal diversity. The tension between identity and politics would not go away simply by breaking up states into smaller polities: different identity categories could become salient.

Session 2: Power-sharing, Constitutions, and Informal Bargains

Our second session moved from concept to structure. Iraq, Kurdistan, and the GCC were core reference points. The guiding question was practical: what makes a “nation” possible when identity differences are real and politically salient?

Dr. Salih’s reflections grounded the discussion. Iraq’s federal democratic structure is young and sometimes still struggles to build consensus among groups. Yet it also offers a mechanism that is easy to miss from afar: elections can draw in popular factions that previously sat outside the system. Dr. Salih described how recent Iraqi elections have shown the involvement of actors that previously seemed opposed to the democratic, federal project altogether.

A demographic fact sharpened the lens. Dr. Patel noted how young Iraq is: almost two-thirds of Iraqis today either were not yet born or were not old enough in 2003 to remember the rule of Saddam Hussein. The size of this youth cohort is changing the meaning of memory, legitimacy, and fear. It also shapes what “post-2003” even means to the average Iraqi citizen: most only know the system described by Dr. Salih. The young age of the Middle East is not a minor detail – it shapes narratives, identities and, consequently, politics.

The group also discussed the informal layer of politics, with its bargains, accommodations, and trade-offs between groups. The work done by these informal institutions is often critical to the functioning and representative potential of a democracy.

Session 3: Syria and the “Great Sorting Out”?

The third session focused on Syria, which was framed as an ongoing political transition with real opportunities and risks. The group was joined by a guest speaker: Joshua Landis, writer and manager of the blog SyriaComment.com and professor at the University of Oklahoma.

Professor Landis offered a framing that served as an analytical counterpoint to earlier sessions. He argued that the conflicts seen in the Middle East in recent decades are, at least in part, a “great sorting out” of ethnic and religious groups. Professor Landis noted that, under insecurity and war, identities can harden. People cluster for protection, militias recruit along communal lines, and territorial control becomes linked to group survival. Over time, pressures increase for borders and identities to align.

Professor Landis’s argument helped the group to disentangle two ideas that are often conflated: identity can be socially constructed, and, yet, identity can become politically binding in violent contexts. The practical implication was clear: constitutions and formal rules matter, but they do not substitute for security, for incentives that make coexistence viable, or for enforcement capacity.

Session 4: Technology, Globalization, and Fragmentation

The final session tied different themes together. We revisited identity not only as a domestic variable but also as one shaped by the broader environment. Technology came up as a great disruptor. Information ecosystems now accelerate identity activation, with the potential both to widen distrust and to create new cross-cutting communities. The direction is not predetermined, and the speed at which this can unfold is new.

Some participants argued that aspects of globalization (e.g., free trade) and transnational crises (e.g., climate change) over the past decades have weakened nation-state identities. Others thought that the contemporary fragmentation of the international system seems to contribute to a resurgence in the saliency of national identities.

The session closed on a point of consensus: identity likely will remain formative in the region for decades. The question is what people and institutions do with it – whether it becomes a driver of fragmentation or a basis for pluralism that works.

Concluding Remarks

This study group clarified mechanisms that shape the salience of various identities in politics and the impact of politics on identity, thus treating identity neither as irrelevant nor as fate. Participants agreed that identity likely will remain a formative element of politics in the Middle East for decades to come. Yet whether identity supports political cooperation or creates further conflict is not preordained: the people of the Middle East will define the region’s future.