During the Fall 2025 semester, MEI Senior Fellows Dr. Youssef Chahed and Hesham Kassem led a study group on the past and future of democracy in the Arab World. Over the course of five sessions, the group explored the Arab world's fight for democracy and its balancing of economic development, human rights, and political freedom.

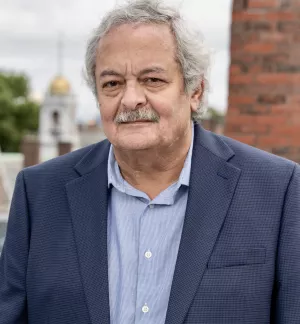

The first session began with an introduction of the courses’ two Senior Fellows, Dr. Youssef Chahed, former Prime Minister of Tunisia (August 2016 - February 2020) and Hesham Kassem, the former publisher of the Egyptian newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm. Each began with a brief overview of their own ties to democratic movements in the Arab world – Dr. Chahed as a Prime Minister in democratic Tunisia, and Mr. Kassem as a member of the media and a contributor to political organizing. The participants, who came from a diverse range of backgrounds, introduced their own experiences: as fellows, as researchers in the region, and as students who came of age in the Arab Spring.

The group began with a broad survey: what is the first word that comes to mind, when one considers the Arab Spring? Participants' answers were varied, capturing both the hopes and the tragedy of the Arab Spring’s history. By far the most popular responses were “revolution” and “democracy.”

Tunisia’s Democracy: What Went Wrong?

Dr. Chahed led the first session with a case study on his homeland, Tunisia. In the aftermath of an autocratic state, the sense of exhilaration and democratic opportunity can be palpable. But it can also be a time of instability. In Tunisia, the birthplace of the Arab Spring, “everyone was involved” in the redevelopment of Tunisia’s system of government and constitution between 2011 and 2014. Cultural and political conflict between secularists and Islamists dominated the Tunisian public sphere. Assassinations and terrorist attacks sparked general horror in the broadly peaceful nation. Questions about the minutiae of constitutional law captured the national consciousness. Democracy, it became clear, would be a project affecting every swath of Tunisian society.

Dr. Chahed zeroed in on the period of Tunisia’s early democratic flourishing to analyze the successes and failures of the post-revolution democratic transition. Students were particularly interested in Dr. Chahed’s personal experiences during this era.

This led to a discussion on the benefits and drawbacks of the 2014 constitution. While decentralization broke the stranglehold of the dictatorial executive, it also weakened the state. Similarly, attempts to reform the judiciary met opposition from the system’s culture, decades in the making. And because no free political class had been permitted to emerge under former Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, there was a lack of viable politicians with name recognition in the transition era – an experience comparable to that of contemporary Syria.

The realities of governance – of the state’s economic trajectory, of the revolution’s impact on bureaucracy and administration, of social pressures on the political apparatus – are a particular challenge in transitional democracies. The group returned to this theme time and again.

Building Democratic Institutions in Iraq

For the second session, MEI visiting fellow Dr. David Patel shared his research on authority building in Iraq, making the argument that Iraq is, if not a democracy, at least democratic. Participants discussed which elements are most necessary for a functioning democracy, including elections, a functioning parliament, or strong civil society protections.

Because Iraq’s constitution was developed in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion, it is often controversial for its taint of occupation. Nonetheless, the constitution and following norms have created a system whereby elections are held routinely and do determine real political power – not strictly along sectarian lines. Other complicating factors in the Iraqi context include the role of foreign intervention from Iran and the United States, the impact of the Sadr family, and the legacy of Grand Ayatollah Sistani.

What explains the relative stability and longevity of the Iraqi political system since the early 2000s? Several answers were proposed, including external guarantors propping up the system, and an elite pact holding the system together. Even so, the progress on elections and peaceful transitions of power has so far failed to stop corruption or provide for the basic needs of the Iraqi people.

Economic & Social Pressures in Egypt

Can political processes succeed without solid economic management? A plurality of the class believed the answer was ‘no.’ For the third session, MEI Senior Fellow Hesham Kassem took this question as his departure point. The third ca2se study introduced Egypt, the largest Arab country by population and the site of some of the largest pro-democracy protests during the Arab Spring.

Kassem introduced many of his own personal recollections in the journalistic industry reporting on elections, referenda, and failed political transitions in Egypt. The Egyptian press was in a constant tug-of-war with overt propaganda outlets, whether analyzing economic policy or its political implications.

The Egyptian case study cast a look back further in history than the research on Tunisia or Iraq. Beginning with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal, it traced a throughline of conflict between political and economic interests in Egypt through to the Sisi government. Nasser’s supporters argued that their fusion of socialist, Arab nationalist, and Third Worldist ideologies justified military sequestration of private businesses – but the process destabilized the relationship between private property rights and the Egyptian government. Limited foreign investment and a lack of transparency in fiscal policy broke down the trust many Egyptians had in state economic management.

Many of these economic policies coincided with military and political challenges – including the 1967 War and the infitah policy introduced after the 1973 War. At times, political repression included economic pressure on opponents; at other points, economic-driven street protests and bread riots have precipitated military crackdowns. But inconsistency and corruption remained constant concerns. With fiscal policy and political power personified in a military-backed leader, “[e]very time a president died, Egypt’s growth died.”

Comparative Cases of Democratic Experiences

The fourth session of this study group brought in two esteemed professors of Middle Eastern political theory: Professor Sharan Grewal of American University, a former Research Fellow at MEI, and Professor Ezzedine Fishere of Dartmouth, a longtime Egyptian diplomat and former Egyptian Assistant Minister for Culture.

While Egypt experienced a military coup in 2013, Tunisia did not. Dr. Grewal argued, as in his book Soldiers of Democracy, that this varied outcome was the result of military culture shaped under autocracy. Because the Egyptian military was empowered under the Mubarak regime and earlier, it executed a military coup during the post-Arab Spring transition. Culturally, the Egyptian military had been heavily politicized, with officers seeing their role as guardians of the state and national security. The officer corps, largely made up of the secular elite, therefore pushed back against civilian leadership of Egyptian national security policy on issues ranging from the incorporation of the Muslim Brotherhood into politics to regional policies towards Ethiopia and Syria.

Dr. Fishere considered the differing paths of Tunisia and Egypt from the developmental perspective. The entire national movement in Egypt was built around the fight for constitutional rule – including, albeit inconsistently, liberal democracy. However, these brief efforts at democratization have repeatedly failed. Dr. Fishere argued that this was the result not of anti-democratic culture but instead endemic state fragility. Personal patronage, applied culturally, economically, and politically, contains social conflicts without allowing for the agency to resolve them. This systemic patronage – what might be termed “Neo-Sultanism” – creates a political culture without compromise or negotiation, leaving conflicts to fester. As such, when democratic openings or transitional periods did occur, the risk of state collapse created opportunities for reactionary, militarized, or autocratic regimes to emerge.

The discussion drew out further comparisons to the Tunisian case. In Tunisia, economic stagnation and administrative failures after the democratic transition created a demand for more authoritative – or authoritarian – government. This, in turn, played into a cycle of corruption. Conversely, a system of resilient institutions, a functioning economy, and governmental checks and balances could ensure a democratic culture in the long term.

The Arab World & “Hard Places” for Democracy

Prof. Tarek Masoud, the Faculty Chair of the Middle East Initiative, joined the final session to speak on his research into “hard places” for democracy. The “Hard Places” approach posits that nations with long histories of autocracy and repression face a particular struggle with democracy. Considering the Muslim-majority, predominantly Arabic-speaking states of the so-called Middle East (alongside the Muslim majority regional powers Iran and Turkey), all fall outside the spectrum of electoral democracies. Some are competitive authoritarian states, and yet the region sometimes appears to be uniquely non-democratic.

While some detractors argue that electoral democracy is itself a Western norm or foreign import, much of the Arab Spring protests voiced a pervasive popular interest in functioning states reflective of citizens’ desires, without corruption or excessive clientelism. What, then, explains the repeated failures of sustained democracy in the modern Arab world?

Many political theorists, for instance, believe that rentierism is adversely correlated to the long-term success of democracy. One might consider the cases of Iraq’s oil, Egypt’s canal, or even the Gulf states’ oil and geopolitical significance. The revenue derived from economic exports which can be extracted at little labor cost mutes demand and limits opportunity for democratization, while funding coercive and repressive apparati. “Modernization theory,” somewhat controversially, argues that as countries develop economically, they become capable of sustaining democracy. Others argue that the legacies of colonialism, cultural-political norms, and even religion impact contemporary political institutions in the region.

Aljohara Almoammar, a Research Fellow at the MEI, offered an alternative perspective on reform and social liberalization in the Middle East. While Iraq, Tunisia, and Egypt all experienced moments of democracy following political transitions – whether as the result of invasions, social revolutions, or coups – states in the Arabian Peninsula have pursued social and economic reform without political transition. In Saudi Arabia and across much of the Gulf, contemporary reform agendas reflect an evolution of the social contract rather than a response to mass protest. Historically rooted in oil-funded public employment and welfare, this social contract is now shifting toward a post-rentier model focused on long-term stability. Reform has emphasized the strengthening of rule of law and institutional accountability through greater transparency, due process, and anti-corruption measures; the promotion of national dialogue and a more inclusive national identity that prioritizes citizenship over tribal or regional affiliations; improvements in governance through more efficient, evidence-based decision-making; and the expansion of social and economic space via economic diversification, decentralization of culture and entertainment, and sustained efforts to counter extremism.

Overall, if there was one takeaway from the group, it dealt with the participants’ understanding of how democratization occurs, and how it sustains itself. Democracy, as a system of governance, allows the people to exercise checks on authority. It thus relies on both the government’s ability to maintain order and stability as well as the people’s ability to impose accountability. Democracy emerges frequently in modern history following the collapse of authoritarian regimes, as in Tunisia, Egypt, and Iraq. The challenge, perhaps, is democracy’s survival.