In 2022, South Africa had a total installed capacity of 63.4 gigawatts (GW) and generated about 230 gigawatt hours of electricity. Fossil fuel-derived generation accounted for approximately 76% of total capacity and approximately 88% of power generation. As a result of South Africa’s abundant coal reserves and stable domestic coal production, the country relies heavily on coal-fired power generation to meet its electricity needs. However, its electric power sector experiences frequent power outages because of insufficient investment in infrastructure.

South Africa is the largest petroleum consumer in sub-Saharan Africa, just surpassing Nigeria. In 2023, it imported about 138,000 barrels per day (b/d) of crude oil, with 66% coming from African countries. Nigeria was the main source of imports, supplying nearly half, or about 60,000 b/d, of the total. Saudi Arabia, the sole supplier from the Middle East, provided about 34,000 b/d, with an additional 13,000 b/d of crude oil coming from the United States.

South Africa has limited natural gas resources that can be commercially exploited, so it imports most of its natural gas from Mozambique. It also has a sophisticated synthetic fuels industry, producing liquid fuels from its gas-to-liquids plant in Mossel Bay and its coal-to-liquids plant in Secunda.

Additionally, the country has two nuclear reactors near Cape Town, with a combined capacity of about 1.9 GW. The government is seeking to expand its nuclear power capacity to 2.5 GW. Hydropower accounts for a small share of South Africa’s total electric capacity and generation because of the relatively dry climate. However, its rivers in the east are used for hydroelectric power generation.

The Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Program (REIPPPP) has successfully attracted private sector investment in renewable energy projects. As of January 2024, the program had procured approximately 6.4 GW of renewable energy from 112 producers. The South African government is now seeking investors to develop an additional 5 GW of new capacity from solar and wind sources, though coal will likely remain its primary fuel source for the near future.

To further diversify its power generation mix, South Africa launched the JET partnership in 2021 with Germany, the United Kingdom, France, the United States, and the EU. The partners committed to providing South Africa with $8.5 billion (R157 billion) to move from coal to renewable energy. After it launched, the partnership attracted additional pledges from the Netherlands, Denmark, Canada, Spain, and Switzerland, with pledges now totaling $11.8 billion (R218 billion). In March 2025, President Trump withdrew the U.S. share of about $1.5 billion (R27.7 billion) from the arrangement, but the other partners remain committed. Funding supports six focus areas: electricity, green hydrogen, new energy vehicles, skills development, a just transition away from coal, and municipal capacity.

Today, South Africa has made progress in advancing policy and regulatory reforms to support the energy transition, including implementing the Energy Action Plan, the country’s national energy security roadmap. It includes a new renewable energy master plan to spur green industries and jobs. South Africa is also a key player in the African Development Bank’s New Deal on Energy for Africa, which emphasizes renewable energy development and regional energy integration. As a result, it plays a critical role in African energy integration. However, its reliance on coal and limited progress in renewables undermines its ability to lead regional transformation.

While South Africa's coal exports and its role in the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) position it as a regional energy hub, it experiences a consistent energy crisis, with persistent electricity shortages and aging infrastructure that weaken its dominance. Its chronic power outages undermine industrial output and GDP growth, weakening its ability to assert geopolitical leadership. Rural energy inequality persists, with many areas relying on paraffin and wood, reflecting systemic inequality. These disparities weaken South Africa’s ability to claim leadership in equitable energy transitions. The country’s slow pace of change can be attributed to institutional lethargy, persistent fossil fuel subsidies, and political resistance from left-leaning politicians and labor unions.

While South Africa has added renewable capacity through programs like REIPPP, it remains far from its 2030 targets. Resistance from coal-dependent communities and industries highlights the sociopolitical challenges of decarbonization. Today, it still relies on coal for 88% of electricity generation.

The country’s dependence on external funding for JET ($8.5 billion) highlights its reliance on Western sources to decarbonize. This reliance makes it vulnerable to geopolitical pressures, particularly as South Africa seeks to maintain balance between BRICS and Western powers. Finally, South Africa’s reliance on gas imports from Mozambique for energy security leaves it vulnerable to geopolitical instability in the region.

In light of these obstacles, South Africa seems unable to exercise energy diplomacy and climate leadership. Failure to meet renewable energy targets weakens the country’s influence in global climate negotiations and limits its ability to compete for green financing. Energy partnerships with both China (through BRICS) and the United States (through JET) illustrate South Africa’s strategic balancing act but risk alienating one bloc over the other.

Technology

Technological innovation is opening a new frontier in the global development agenda. Artificial intelligence (AI) has already had a profound impact on global issues in agriculture, health care, education and more. The potential for AI tools to drive economic growth is tremendous, but the economic and social benefits of this technology remain concentrated in the Global North. AI could contribute up to $15.7 trillion to the global economy by 2030, but North America and China are projected to see the largest GDP gains. In contrast, countries in the Global South will experience more moderate increases due to their much lower rates of adoption. Unsurprisingly, developed nations with more economic power are best positioned to fund research and development to deploy the latest AI technologies.

Indeed, a recent Oxford Insights assessment of 181 countries and their preparedness for using AI in public services found that the lowest-scoring regions include much of the Global South. In Africa, Mauritius, South Africa, and Rwanda lead the field, showing strong momentum in developing AI ecosystems, particularly in data and infrastructure development. South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Kenya have all released AI strategies, as has the African Union.

However, from the perspective of the Global South, the problem runs deeper. Analysts speak of “digital colonialism” or “technological colonialism,” a new form of economic exploitation in which a handful of developed nations try to maintain their technological dominance, with an aim to collect more raw data — the most critical resource in the digital era. These countries reinforce their position by steering global technology governance and perpetuating the exclusivity of advanced technologies. As one commentator in Al Jazeera observed, “Big Tech corporations use proprietary software, corporate clouds, and centralized Internet services to spy on users, process their data, and spit back manufactured services to subjects of their data fiefdoms.” As great power rivalry and geopolitical tensions intensify, the politicization and weaponization of technology deepens this fragmentation in some high-tech sectors.

South Africa aims to position itself as a digital economy leader, fostering innovation, job creation, and inclusive economic growth. Indeed, a recent assessment by the U.S. International Trade Administration (ITA) identifies South Africa as a leader in Africa’s digital economy due to its advanced digital infrastructure, vibrant startup ecosystem, and proactive government committed to fostering digital growth. The ITA projects that the digital economy will account for 15% to 20% of South Africa’s GDP by 2025, up from 8% to 10% in 2020, with an anticipated annual growth rate of 10% to 15% for the next five years. South Africa’s e-commerce market is expected to grow at approximately 12% compound annual growth rate through 2025, reaching $10 billion and accounting for 5% to 6% of overall retail sales, up from 2% to 3% in 2020.

As noted by Chief Editor of TechAfrica News Akim Benamara, South Africa’s strategic location and relatively advanced infrastructure have positioned it as a regional digital hub and a leader in setting the pace for digital development in sub-Saharan Africa. The country ranks 73rd out of 188 in the 2024 Oxford Insights’ Government AI Readiness Index and is listed alongside Botswana and Senegal as among the top three innovation economies in sub-Saharan Africa in the 2024 Global Innovation Index.South Africa's Digital Economy Master Plan (DEMP), which aligns with its National Development Plan 2030, prioritizes 5G deployment, digital skills and workforce development, digital infrastructure and innovation, technology startups, e-government services, and cybersecurity. In 2024, South Africa introduced the Draft National Artificial Intelligence Plan, signaling its commitment to AI, cloud computing, and blockchain adoption as key pillars of its digital economy.

Five key trends are shaping South Africa’s digital economy and increasing its adoption:

Investment in Digital Infrastructure

Over the last five years, major telecom companies have invested approximately $5 billion to establish fiber optic networks and data centers, improving connectivity and expanding digital capacity. These include firms such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, Teraco, and Dimension Data.

Mobile Connectivity

South Africa is a mobile-first economy, with more than 90% of internet users accessing the web via mobile devices. Expanding 4G and 5G networks will improve access to digital services.

Increasing Internet Penetration

As of January 2024, South Africa had 45.34 million active internet users, representing 74.7% of the population. Internet users increased by 409,000 from January 2023 to January 2024, a 0.9% increase.

Government Initiatives

The South African government is prioritizing energy and logistics reforms to support digital growth alongside various e-government initiatives, such as online tax filing, digital identity systems and passport applications, and vehicle licensing. Additionally, cities like Cape Town and Johannesburg are exploring smart city initiatives, using technology to improve urban services.

Tech Hubs and Startups

Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban are emerging as tech hubs with a vibrant startup sector, particularly in FinTech, HealthTech, and EdTech, attracting both local and foreign investment. In a recent article published by the World Economic Forum, Simmonds and Nunoo argue that Africa could position itself as a key partner if it adopts the right policies and investments. They list three advantages in Africa’s favor. First, the continent is rich in the critical minerals essential for semiconductor production, including cobalt, tantalum, and rare earth elements. Second, Africa boasts a young, expanding workforce, with a growing number of STEM graduates. Countries including South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, and Kenya are investing in technical education and innovation hubs, creating a talent pipeline for the semiconductor industry. Finally, Africa's strategic location — between major markets in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia — enhances its appeal for global trade. Assembly, testing, and packaging present an opportunity to enhance supply chain diversification and support global technological progress.

Because of their essential role in modern technology, semiconductors are a cornerstone of the digital world. The global semiconductor industry, dominated by Samsung, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), and NVIDIA, is undergoing rapid transformation, driven by rising demand, geopolitical shifts, and the need for more diversified and resilient supply chains. The United States, EU, and Japan are actively seeking to diversify their supply chains, marking an inflection point for semiconductor manufacturing and creating potential openings for new partners.

South Africa's semiconductor industry is nascent, but the government is actively promoting its development as a strategic sector for growth. The country has made some early investments in research and development, with initiatives like the Microelectronics and Nanotechnology Centre at the CSIR focusing on semiconductor design and production. Africa’s integration into global semiconductor supply chains could have far-reaching benefits, enhancing supply chain resilience, reducing overreliance on East Asia’s semiconductor industry, and supporting long-term industry sustainability. More generally, as Africa industrializes, its role in advanced manufacturing will drive economic growth, create jobs, and foster even greater technological innovation.

Missed Opportunity: Space Technologies

In the 1960s, NASA established a deep space tracking station in Hartebeesthoek, which contributed to missions such as the Apollo moon landings and laid the foundation for South Africa’s involvement in space science and satellite technology. Today, the Hartebeesthoek site is part of the South African National Space Agency (SANSA), established in 2010, which has supported more than 600 global missions and hosts infrastructure for clients in the Global North.

According to SANSA, approximately 20 privately-owned space engineering companies export $1 billion annually in space-qualified components, subsystems, and satellite systems, with an ambitious target of $10 billion by 2030. Yet, despite its National Space Strategy, which aims to strengthen South Africa’s local space industry, the country remains primarily an end-user of space technology rather than a developer of homegrown systems and capabilities.

Across Africa, however, the space sector is thriving. Twenty African countries now have national space programs, and 15 of these have launched satellites into orbit. Egypt, South Africa, Nigeria, and Morrocco have five or more satellites in orbit, while Ghana, Mauritius, Rwanda, Sudan, Tunisia, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Kenya each have one. Sophisticated astronomical telescopes can be found on all four corners of the continent, and South Africa is home to the world’s largest radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array, anticipated to be fully operational by 2025.

In 2022, Nigeria and Rwanda became the first African countries to sign the NASA-led Artemis Accords, aimed at outlining best practices for sustainable space exploration (South Africa is not a signatory). Several U.S. companies have also pledged to deepen their partnerships in space exploration with African nations. Previously, collaboration with established space agencies has helped African counterparts access existing knowledge and technology, bypassing the need to start from scratch. For instance, Djibouti and Hong Kong Aerospace Technology Group Ltd. have agreed to construct a new spaceport in northern Djibouti within five years. Its location near the equator makes it an ideal place for launching satellites.

Many African nations are committed to harnessing space technology to address their unique socioeconomic challenges. Countries like Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, and Ethiopia are developing space innovation ecosystems, often in partnership with private-sector actors. In these jurisdictions, startups and entrepreneurs are increasingly leveraging space-based technologies to create practical solutions, making the sector more inclusive than it was in the past.

Now, in an effort to reclaim its earlier prominence, South Africa aims to play a central role in fostering space development across the continent. It seeks to facilitate technology transfer, capacity building, and training programs to support emerging space initiatives. By positioning itself as a regional hub for space science and technology, South Africa hopes to strengthen Africa’s collective space capabilities, ensuring that the continent benefits from advances in satellite technology, communications, and scientific research. To achieve this, it will need both the right policies and increased investment — critical thresholds it has not yet crossed.

Digital Economy: Regulatory Challenges

Although the South African digital economy is growing, its potential is hampered by eight regulatory challenges:

Data Privacy Regulations

South Africa’s data protection ecosystem is primarily governed by the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), which took effect in 2021. POPIA defines personal information broadly and grants data subjects rights such as being informed, accessing their data, and objecting to processing. Cross-border data transfers are only allowed under specific conditions, such as when the recipient country has adequate data protection laws, when binding corporate rules or agreements are in place, when data subjects give consent, or when the transfer is necessary for contract performance. Financial institutions and telecom firms face stricter data residency requirements.

AI Regulation

South Africa currently lacks specific AI regulations and is still developing a national AI policy framework.

Cybersecurity

South Africa has one of the highest rates of cybercrime in the world. The Cybercrimes Act (2020) provides a framework to combat cybercrime, but implementation and enforcement remain challenging, as more comprehensive and enforceable regulations are needed. Many companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), lack adequate cybersecurity measures, making them vulnerable to attacks. Compliance can be expensive for businesses, particularly those required to follow multiple standards, such as POPIA and the Cybercrimes Act.

Online Harms Regulation

South Africa does not yet have a comprehensive framework regulating online harms such as disinformation, hate speech, and online abuse. The absence of clear guidelines leaves businesses and users uncertain about their responsibilities and protections.

Subnational Markets

There is a significant digital divide between South Africa’s urban and rural communities, with rural subnational areas facing limited broadband access, difficulties with connectivity, low digital literacy, and a shortage of technology.

Market Entry

Foreign companies entering the South African digital market face multiple regulatory hurdles, including compliance with POPIA (data protection), Black Economic Empowerment laws, and various sector-specific laws, especially in emerging digital sectors. Regulatory compliance, local procurement laws, and localization pressures can make market entry expensive and difficult, particularly for SMEs or startups competing against established local and international players.

Public Sector Procurement

Public sector procurement is tightly regulated to ensure transparency and fairness, but processes can be slow and often favor large, well-established corporations. New entrants and SMEs face barriers to penetrating the public sector due to lengthy bidding processes and complex compliance requirements.

Dependence on Foreign Technology

The country is heavily dependent on foreign technology from the United States, China, and European nations. It has sought to maintain a balanced approach amid U.S.-China technology competition, actively engaging with both countries.

South Africa’s status as a regional tech hub is reinforced significantly by the presence of major U.S. technology companies, such as IBM, Cisco, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Facebook. These firms have subsidiaries in South Africa and use it as a base to serve other African markets. Additionally, as previously mentioned, South Africa cooperates with the United States on space initiatives, particularly in satellite programming. Meanwhile, China has become a major player in South Africa’s information and communication technology sector, particularly in cybersecurity and smart infrastructure development. Huawei, operating within the framework of China’s Digital Silk Road, has led multiple initiatives as the primary 5G supplier for telecom companies and smart cities development projects across the country.

Still, several factors conspire to prevent South Africa from realizing its position as an African digital economy leader, including economic instability, political uncertainty, and regulatory constraints. The country has yet to realize its potential as a continental leader in space technology, semiconductors, or digital communications.

Starlink, the world’s most advanced satellite internet system, highlights both the challenges and opportunities of technological expansion in South Africa. Orbiting about 550 kilometers above Earth, its roughly 7,600 satellites (out of more than 12,000 in orbit) deliver high-speed internet to customers around the globe. Operated by SpaceX, a space tech firm headquartered in Texas, the system offers many advantages to a developing country like South Africa — and, in fact, to all of Africa. Starlink also stands to benefit from exploiting Africa’s increasingly sophisticated digital markets.

Despite its advantages, SpaceX has found it difficult to set up shop in South Africa. CEO and Founder Elon Musk has publicly voiced concerns over the country’s growth and stability under the leadership of the ANC, and the company faces complex domestic regulations. Still, Musk has decided to “go big,” offering to build regional infrastructure in the form of a network of earth stations with fiberoptic connections to data centers to support the entire Southern African Development Community region. At the time of writing, Starlink was in negotiations with the South African government.

Additionally, there are other more ominous reasons for the delay. Joscha Abels recently argued that Starlink’s wartime role in Ukraine and Iran offers a striking example of how modern communications can change the course of conflicts. It provides a cautionary tale about the reliability of critical systems in the hands of private corporations and powerful individuals. Moreover, Starlink and similar satellite networks pose disruptive risks to the country’s premier astronomical facilities, including the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT) and the ambitious Square Kilometre Array project. Existing safeguards to minimize interference exist only within national borders, leaving space-based satellites outside the scope of local regulations. Although the South African government recognizes these risks to national security, it has yet to develop a thoughtful, coherent response.

U.S. and China Ties

The South African government hopes to benefit from the emergence of a multipolar world order. It does not believe a superpower contest between the United States and China defines global affairs. Instead, it pursues “strategic autonomy,” or hedging between alliances, maintaining trade and political relations with BRICS, the United States, and the EU. However, this balancing strategy has strained relations with the Trump administration and may risk alienating other Western allies. Further, South Africa’s approach is limited by resource constraints and political pragmatism, complicating its access to critical funding for its energy transition, digital economy ambitions, and continental leadership aspirations as an African middle power.

U.S. Ties

The return of the Trump administration on the global stage has soured the relationship between South Africa and the United States, as Washington manipulates trade preferences, aid programs, and tariffs to achieve political objectives. Africa occupies a marginal place in the administration’s worldview, except where and when it serves American economic or strategic interests, such as securing access to rare earth minerals, countering violent extremism or organized crime, or curbing Chinese and Russian activities across Africa.67 Within this context, the administration’s Africa team favors a review and reset of the relationship with South Africa,68 citing the government’s close relations with countries perceived as U.S. enemies primarily Russia, China, and Iran, as well as others such as Cuba and Nicaragua. The South African government’s preference for an “active, nonaligned” foreign policy posture, which in practice prioritizes relations with BRICS members, has become problematic for its Western allies and trading partners.69

South Africa’s active role in bringing Israel before the International Court of Justice to account for its alleged genocide in Gaza, and its support for the International Criminal Court in seeking arrests for Israeli and Hamas leaders for war crimes, has deepened unease among its Western allies and trading partners.70 In February 2025, Trump issued an executive order halting foreign aid and assistance to South Africa.71 His administration also withdrew support for South Africa’s Just Energy Transition and expressed disdain for the G20, whose summit is scheduled for November 2025 in South Africa.72

This shift is forcing a recalibration of U.S.-South Africa relations, with expected negative consequences in the short term for trade and cooperation on African conflict resolution. If this transpires, South Africa is likely to strengthen its relationships with China and other BRICS members, pursuing an Africa-oriented strategy for trade and security cooperation in the medium to long term.

China Ties

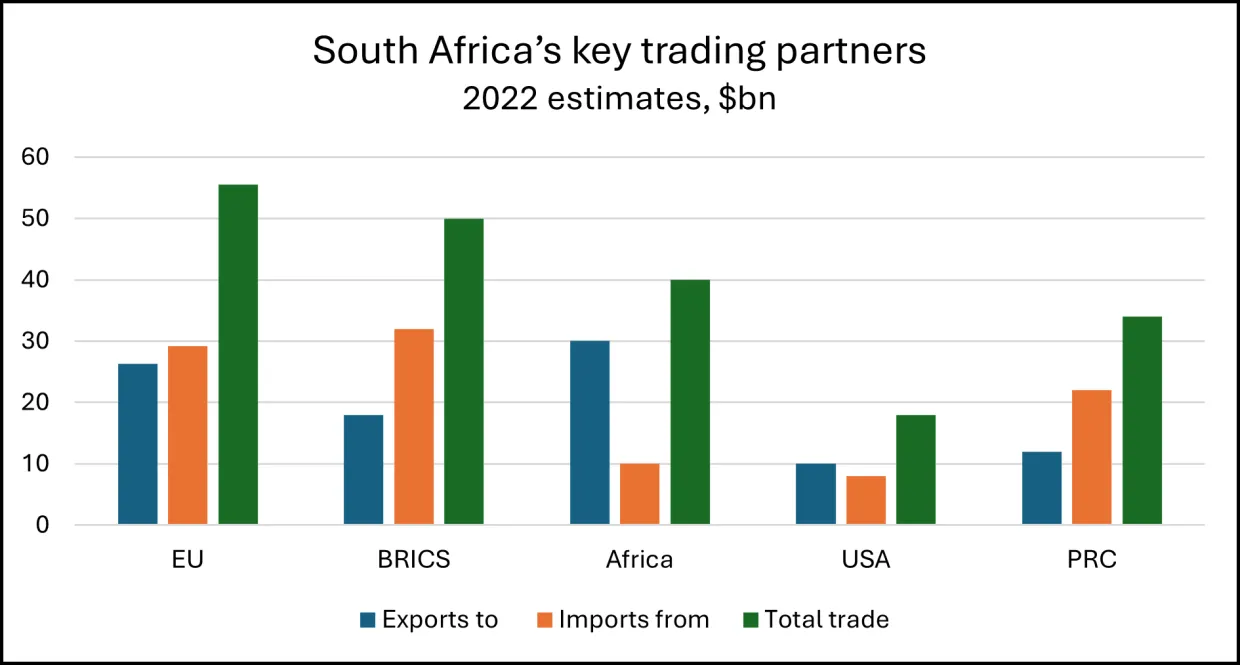

China’s continued involvement in the South African economy is expected to strengthen industrial and supply chain cooperation, positioning their partnership as a model for Global South economic collaboration and driving economic recovery beyond Africa. However, South Africa’s trade deficit with China reached $9.71 billion in 2023, raising concerns about long-term economic sustainability.74 While Chinese demand for mineral resources has fueled South African exports, local beneficiation and industrial diversification remain limited.

The ninth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Ministerial Conference in 2024 highlighted the need for South Africa to expand agricultural exports and invest in value-added industries to reduce dependency on raw material exports. At the same time, local industries face challenges due to competition from low-cost Chinese imports in sectors like textiles, electronics, and, increasingly, motor vehicles. Calls for tariff protections and import substitution policies are growing as South Africa looks to balance economic cooperation with domestic industrial growth.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Momentum for reforming the instruments of global governance could be led by a coalition of Global South nations, including South Africa, the expanded BRICS alliance, and like-minded European and Asian nations. Most Global South middle powers are broadly aligned in pursuing a reset of the so-called rules-based international order to accommodate their national interests. The enlarged BRICS alliance, now 10 members, with several others waiting as associate members, stands out as the primary platform for this effort, motivated by a focus on improving trade and investment opportunities and strengthening the role of the UN system as a foundation for equitable global governance.

However, it remains unclear whether South Africa can cohere with both the North and South. BRICS is increasingly challenging the G20’s dominance. While the OECD describes the G20 as the “premier forum for international economic cooperation,” the United States and Germany played a founding role, and it has faced much criticism in terms of its standing and impact. The G20 is often seen as a protector of the Western-led international financial order, and its attempts to reform “from within” are often met with skepticism.

Is this an appropriate vehicle for the Global South to push a reform agenda? In explaining South Africa’s focus as G20 chair in 2025, its foreign minister pledged to provide strategic direction toward establishing a “more equitable, representative and fit-for-purpose international order.” But under the new global conditions created by the Trump administration, the G20 may struggle to tackle shared global challenges like climate, public health, inequality, poverty, and digitalization to the benefit of both the Global South and North.

Beyond the attempt to steer the G20 toward a “development-friendly” agenda and shape global discourses on multilateral reform, South Africa sees BRICS as its preferential partner. While not aiming to replace the West, BRICS’ assertive stance and its pursuit of greater representation and influence in global affairs signify a considerable challenge to the U.S.-led international order.

Ideologically, South Africa is closer to several BRICS alliance members than to the G20. The African National Congress — no longer a ruling but still a dominant coalition partner in a new government of national unity — professes “progressive internationalism” and has forged close political relations with Russia, India, and Brazil, as well as a deep economic relationship with China. This elevated bilateral partnership stands in direct contrast to the much-reduced bilateral relationship between South Africa and the United States, which arguably peaked during the Gore-Mbeki years. Few analysts expect a positive reset of the relationship under the Trump-Ramaphosa administrations.

South Africa thus stands to lose its long-standing cordial relationship with the United States. The two countries’ foreign policy goals are at odds, leaving little room for accommodation, and the Trump administration’s approach to conflict resolution in Africa is viewed with skepticism. For the United States, South Africa might be seen as a useful entry point to counter the growing influence of Russia and China in Africa. However, given current dynamics, rapprochement seems unlikely, at least for the next five years.

Conversely, China continues to recognize South Africa’s benefits as a reliable partner and African leader with whom it can collaborate on business, peacebuilding, and reforming global governance in the interests of the Global South.

Looking beyond G20 and G7 Summitry, global leaders — particularly fellow middle powers — can seek to build consensus around the following themes:

- Strengthening Africa’s peace and security architecture through policy development, training, and judicious deployment of envoys and mediators to address regional hotspots in the Sahel, the Horn, and Central Africa.

- Supporting the nascent African Continental Free Trade Area by assisting and promoting intra-African trade as well as African trade with Western and Eastern partners, including training for business and trade negotiators, strengthening AGOA’s reach, and incorporating the Chinese BRI into Africa’s Vision 2063 plan of action.

- Cooperating on the threats of climate change. Africa has taken steps to address the biodiversity crisis and aims to integrate the AU’s Agenda 2063 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals into the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. However, unending violent crises fueled by resource exploitation undermine these efforts. The Democratic Republic of Congo, which has Africa’s largest unspoiled biome, cannot advance these objectives without international cooperation on conflict resolution, peacebuilding, and improved policies around responsible resource management. By working with South Africa, a recognized leader in biodiversity management, the United States and China could find common ground in supporting this project.

Statements and views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors and do not imply

endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and

International Affairs.